Introduction

February 5th 2025 will see the 100th anniversary of the Hallé Choir’s first broadcast on the BBC. In this two-part blog I will look at a century of the choir’s appearances on BBC Radio. In this first part I will look at the establishment of the BBC in 1922 and how its commitment to music, and in particular classical music, led to this first appearance on the airwaves.

To begin at the beginning, on May 4th 1922 the Postmaster General Frederick Kellaway announced in Parliament his intention to permit a limited number of radio broadcasting stations to be established, and that a committee of interested parties, including the main manufacturers of the new ‘wireless’ equipment, would be set up to decide the strategy. Though on receiving their report Kellaway agreed that no more than two separate broadcasting licenses should be awarded, a further investigation by a sub-committee of two recommended that a single broadcasting company should be formed. Kellaway agreed to grant such a company an exclusive right to broadcast providing that guarantees were made that such a service could be maintained for a reasonable length of time. Six wireless manufacturers provided just such a guarantee and on October 18th 1922 the British Broadcasting Company Limited was formed. The fledgling company received its license to broadcast on January 18th 1923, though since matters were settled well in advance of this the BBC was actually able to start broadcasting on November 15th, 1922.

Given that the maximum distance from a transmitter any listener had to be at the time to get a reasonable signal on their new radio sets was only between 15 and 20 miles, the new company undertook to operate 8 broadcasting stations to cover the major centres of population. Stations in London, Birmingham and Manchester had already been set up and through 1923 the BBC set up new stations in Newcastle, Cardiff, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Bournemouth. A further nine were added soon after.

This was the general pattern through the rest of the 1920s, with the BBC broadcasting locally via these regional stations, each of which had a 3-digit identifier, the most famous being London’s 2LO. For the purposes of this blog the next most important was the station set up in Manchester, 2ZY, located first in Dickinson Street but eventually settling into purpose built studios in Piccadilly Gardens. In the early days each station had its own programming but very soon news bulletins and other speech and musical programmes were simultaneously broadcast across all the stations.

Music and the BBC

Under their general manager, the formidable John Reith, the BBC’s mission was, and still is, to ‘inform, educate and entertain’, and to this end music was an important part of the company’s output from the very beginning, not just the popular music and dance bands of the day but also a generous helping of classical music.

In the early days deficiencies in recording technology meant that all music was performed live. Orchestras and choirs were set up by the BBC with the express purpose of providing this musical output. In London the Wireless Orchestra was established, gradually growing in size until its transformation into the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1930. 1924 saw the formation under conductor Stanford Robinson of a full-time professional choir, the Wireless Chorus, renamed as the Wireless Singers in 1927 and as the BBC Singers in 1934 and thankfully still with us today and celebrating their centenary in 2024. In Manchester the 2ZY Orchestra was formed in 1922 to perform for that station. Like the BBC Singers it has been through many names – Northern Wireless Orchestra, Northern Studio Orchestra, BBC Northern Orchestra, BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra – but is still with us today as the BBC Philharmonic.

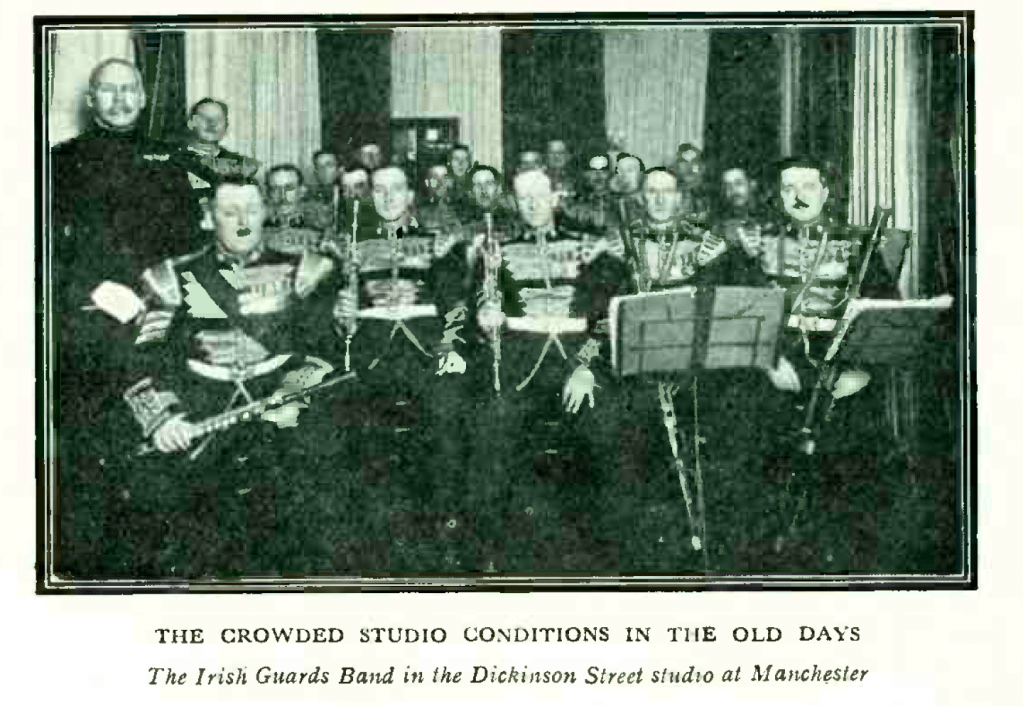

Many musical broadcasts were from studios, often, as can be seen from this photo of the Irish Guards Band squashed into the Dickinson Street studio in Manchester, in very cramped conditions.

However, from the very beginning the BBC would broadcast live from concert halls and opera houses. The very first ‘outside broadcast’ was as early as January 1923, a live performance of Mozart’s Magic Flute given by the British National Opera Company at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. June 1923 saw the first symphony concert to be broadcast, and later in the year a series of operas was broadcast from Birmingham. The year also saw a broadcast that was a harbinger for the broadcast of choral music by a choir such as the Hallé Choir, a performance of Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang from Newcastle.

The years that followed saw further developments, not least the transformation of the private British Broadcasting Company into the public British Broadcasting Corporation in January 1927, paid for by a tax on receiving sets and with John Reith becoming the first Director General. An experimental high-power long wave station, 5XX, was set up in Chelmsford in 1924. 5XX moved to a new site in Daventry the following year and was able to broadcast programmes to the whole of the British Isles, enabling the creation of a truly national service. The 1930s saw the end of the 3-digit stations but a continuing distinction between National programming and Regional programming. The Second World War saw the emergence of the Home Service in 1939 and this was followed by the Light Programme in 1945 and the Third Programme, a new home for speech, drama and classical music at the BBC, the year after. 1967 saw the Light Programme split into Radios 1 and 2, the Home Service become Radio 4 and the Third Programme become Radio 3, the station that today still contains the bulk of the BBC’s classical music output. Over the years the Hallé Choir has appeared on most of these stations!

To return to the early years of the British Broadcasting Company, it seemed only a matter of time before the Hallé Concerts Society would want to get on the broadcast bandwagon. In 1924 they did, and as will be shown below, they soon involved the choir in their broadcast activities via the composer closest to the choir’s heart, Edward Elgar.

The Hallé Choir and the BBC – The Beginning

In his 1960 history of the Hallé Michael Kennedy described the point in 1924 when the Hallé Concerts Society first decided to make overtures to the BBC with regard to the broadcasting of concerts. Note how similar the discussions are to later discussions were about, say, whether the advent of television would affect attendance at cinemas:

Broadcasting was mentioned for the first time [in early 1924] when Gustav Behrens announced that the committee had agreed that a charity concert in the Free Trade Hall could be broadcast on the Manchester Station 2ZY. Arrangements were made for part of 10 of the Society’s concerts in the following season to be broadcast. The committee held that broadcasting was unlikely to affect attendances and was even likely to increase them. In any case, the difference between the ‘live’ concert and what came out of a loudspeaker at that date was so enormous that the matter cannot have given much pause.

from Michael Kennedy – ‘The Hallé Tradition’ (1960), pp 221/2

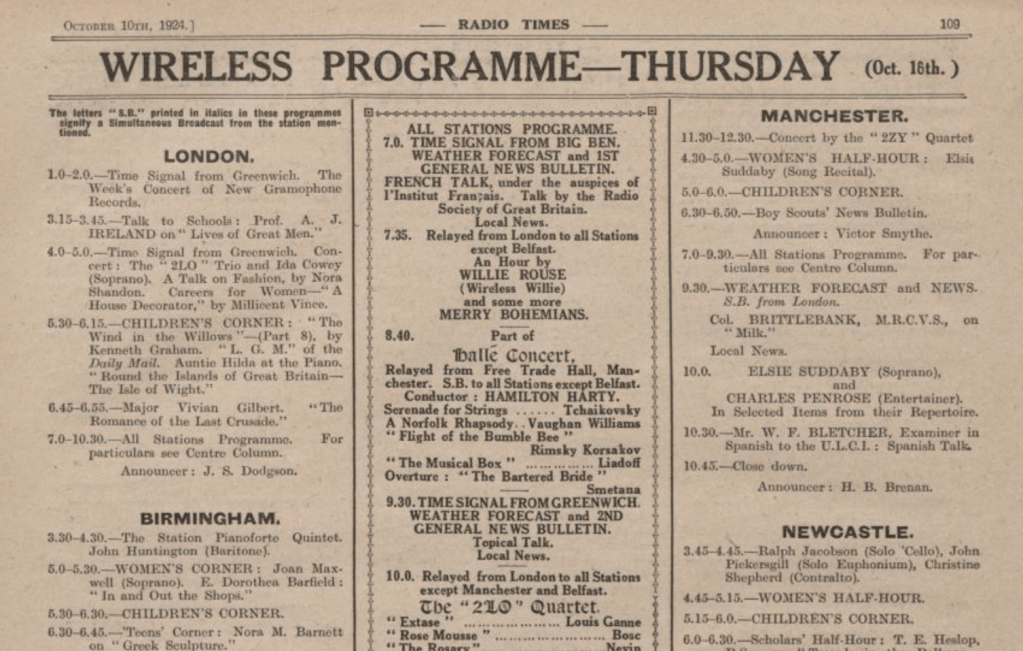

October 16th 1924 therefore saw the very first live relay of part of a Hallé concert from the Free Trade Hall. It was conducted by the chief conductor Hamilton Harty. It included two works which would fit very well into present-day Hallé concerts, Vaughan Williams’ Norfolk Rhapsody and Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, plus works by Rimsky Korsakov, Lindoff and Smetana that might be slightly more unexpected. Interestingly, though the committee had talked of broadcasting on the Manchester station 2ZY, this concert was actually what the BBC alternatively called an ‘all stations programme’ or ‘simultaneous broadcast’ (also known as an ‘S.B.’), meaning that it was transmitted simultaneously across all the BBC’s stations.

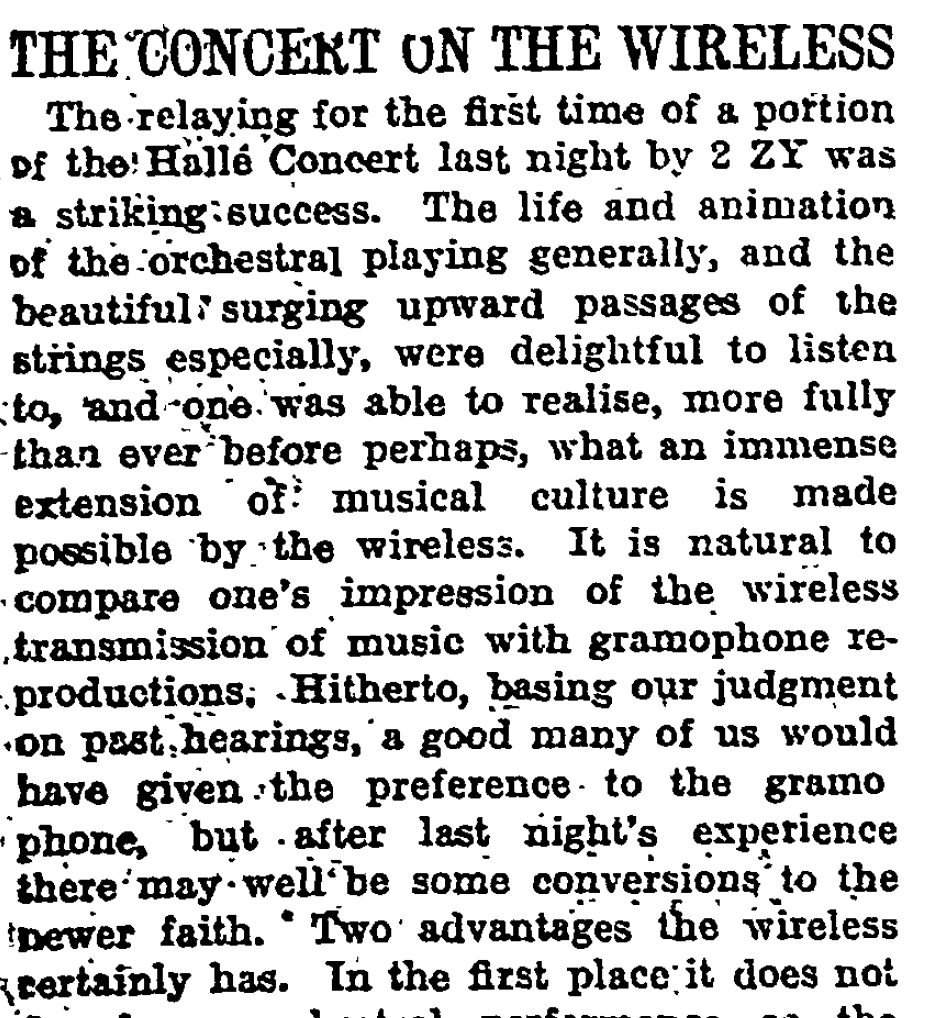

The following day the Manchester Guardian included two reviews, one as one might expect from Samuel Langford in the hall, but one from a correspondent listening to the concert on the ‘wireless’, who considered it a ‘striking success’.

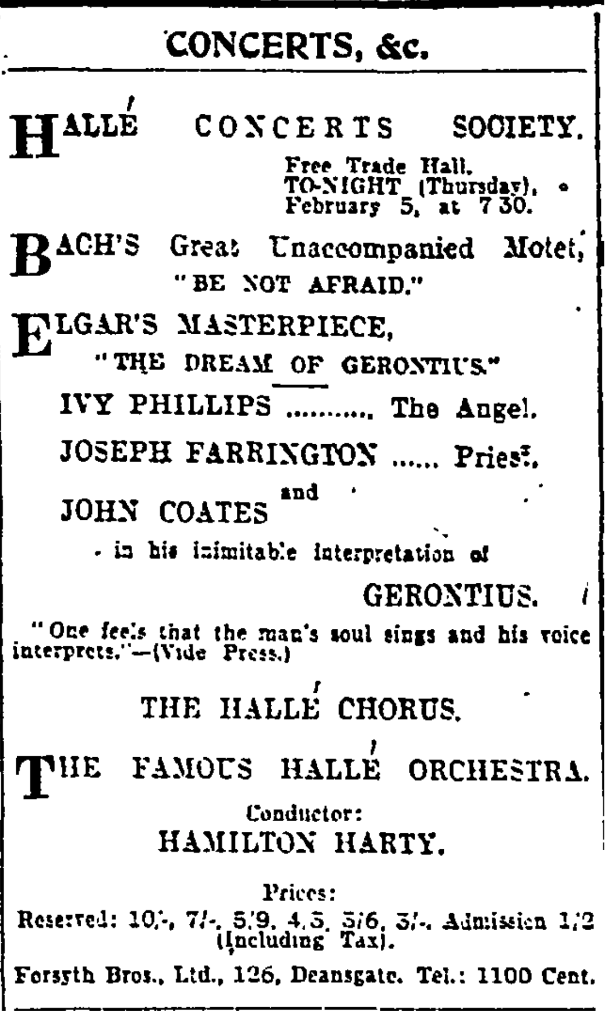

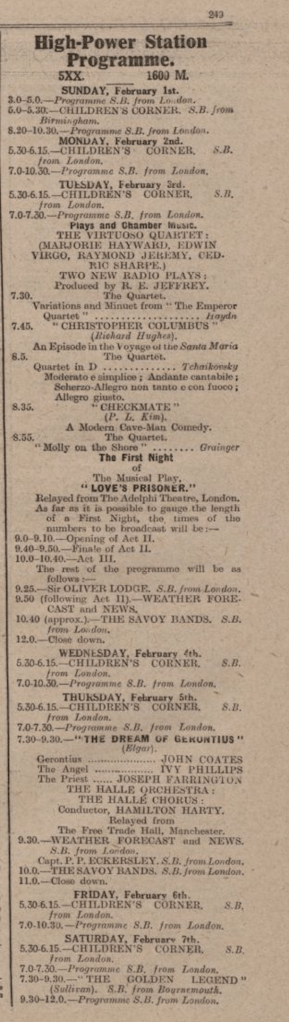

Many Hallé concert broadcasts followed over the next few weeks, and it was only a matter of time before the Hallé Choir featured in one of them. It was also probably inevitable that the concert would feature a composer and a work with which the choir had become inextricably linked over the course of the previous two decades and with which the choir is still linked today, Edward Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius. I talked in a previous blog about how it was that the Hallé Choir, their choirmaster R.H. Wilson and conductor Hans Richter had put the work properly on the British musical map after its disastrous premiere in Birmingham. Many performances followed over the years and the one chosen for broadcast took place in the Free Trade Hall on February 5th, 1925, with Hamilton Harty conducting the choir under their choral director Harold Dawber and with the Australian contralto Ivy Phillips, English bass-baritone Joseph Farrington, and veteran English tenor John Coates as Gerontius.

It wasn’t the first time that the first time the BBC had broadcast Gerontius, or indeed the first time that the BBC had broadcast it from Manchester. On April 20th 1924 there had been a performance of Gerontius on 2ZY with the the 2ZY Augmented Orchestra and the 2ZY Opera Chorus operating, under the banner of the ‘2ZY Opera Company’, conducted by Dan Godfrey Jr, who also happened to be the Station Manager at 2ZY. This appears to have been a studio broadcast so I think we can safely say that the broadcast the following February was the first ever broadcast of a live concert performance of Gerontius.

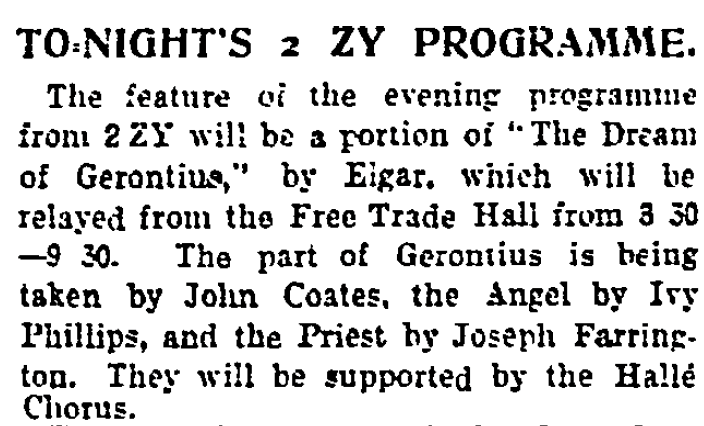

Unlike the first Hallé concert broadcast this was not a simultaneous broadcast and only 2ZY of the regional stations carried it. However, it was also broadcast on the new 5XX long wave transmitter, thus meaning it could reach the widest possible audience. The preview in the Manchester Guardian and the extract from Radio Times show, however, that whilst listeners to 5XX could hear the whole of the concert anyone tuning into 2ZY would only hear Part 2 of the oratorio. At 7.30, the time the concert actually started, they would have heard a ‘Vocal and Instrumental Hour’ with works by Schubert, Debussy, Chopin and others performed by contralto Anne Thursfield and pianist Granville Hill.

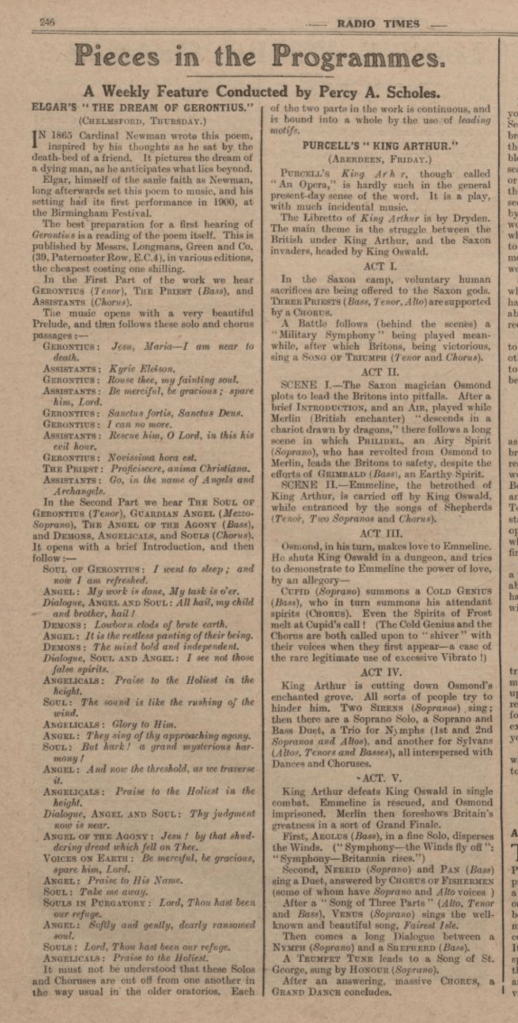

It was also promoted prominently within the January 30th issue of Radio Times, with the renowned musicographer Percy Scholes devoting part of his weekly column to a brief introduction to Gerontius.

There were two types of radio receiver that listeners would have used to tune into the Hallé Choir’s first radio broadcast. The older technology was the crystal set, many of which were homemade. It was very difficult to separate out stations on these sets and they generally were only able to pick up the strongest local station. Also though amplifiers could be attached with difficulty, they were most likely to be listened to through headphones rather than a speaker, making the act of listening very much a private affair. These were soon superseded by newer valve radio sets. Though the earliest of these were used with headphones, it was soon possible to add enough amplification to power a speaker, and as shown in the photograph of the Marconi V2A receiver, these were soon being built into the radio set. With improvements, this type of set became the standard until the advent of the transistor in the 1940s allowed smaller, more portable radios to be produced in the late 1950s and the 1960s.

The actual sound of the choir and orchestra in the Free Trade Hall would have been picked up by moving coil microphones such as the Marconi-Sykes magnetophone, the first custom-built microphone that the BBC commissioned. It was much more sensitive at picking up sound than previous technology, and was in the BBC’s famous live outdoor broadcast in 1924 of the cellist Beatrice Harrison playing in her garden. As an aside, in this broadcast Harrison was supposedly accompanied by nightingales singing in the garden, but the BBC now admits that these sounds were made by a bird impressionist! As this passage explains, however, when set up to record these microphones were very bulky affairs:

[It was] housed in a magnetised cylindrical iron pot which made it extremely heavy. The aluminium coil was so fragile it needed to be supported by a backing paper, which was then supported by cotton wool pads covered with Vaseline or butter. Due to the extreme sensitivity of the microphone coil, the cotton wool was needed to dampen the movement slightly. The mic was hung from a rubber sling to reduce outside vibrations affecting the coil, inside a copper mesh cage on wheels (known as the ‘meat safe’) to reduce electromatic interference being picked up.

from Science Museum Group description of Marconi-Sykes magnetophone

The presence of such microphones meant that the audience in the Free Trade Hall would have been very aware that the concert was being broadcast. For every live broadcast the choir has ever made there has always been the contrast between what the audience in the hall hears and what the audience at home hears. The way that microphones are placed and different sections of the choir and orchestra are balanced can mean that the radio experience is very different to the concert hall experience. Luckily, for this concert the Manchester Guardian, as for the first Hallé broadcast, gave us reviews of both experiences. For Samuel Langford, reviewing the concert from the perspective of the Free Trade Hall, the performance was ‘admirable’, with the choir front and centre of the performance, both in the full-chorus and semi-chorus passages:

…this performance of “Gerontius” was one of the finest Elgar performances we have had for many years, and when we consider the complexity of the work it may well be called admirable… …the singing of the chorus was excellent in its purity and variety of tone, and especially the semi-chorus was beautiful in tone and without the precarious quality of intonation which so much beset the work in its earlier years.

Samuel Langford’s review of the live concert – Manchester Guardian, February 6th 1925

‘R.B.’, also wrote a review, but this time from the perspective of a radio listener. Given that he talked about it being a broadcast of part of the oratorio he was obviously listening on 2ZY rather than 5XX. Though he liked the performance, he was obviously subject to the vagaries of the radio signal, and at least initially had problems picking out both the orchestra and the choir. This suggests that the soloists may have more closely miked, though his comments also suggest that the BBC engineers may have been adjusting the balance on the fly:

So far as the persistence of land-line noises allowed a fair judgement, the wireless transmission of part of “The Dream of Gerontius” from the Free Trade Hall last night seemed a good one. In the hearing as a whole the solo voices came through better than the orchestra and chorus, although from the chorus’s second entry onwards, and particularly where the colour of the music lightened and its style became more pointed, there was a marked improvement both in clearness of reception and in the general balance of instrumental and vocal tone.

“R.B.”‘s review of the broadcast concert – Manchester Guardian, February 6th 1925

Now their broadcasting career had finally begun, the choir proceeded to make many appearances on the BBC through the rest of the 1920s, in both concert and studio settings and with a variety of instrumental accompaniment. In Part 2 of this blog I will look further at the choir’s broadcasting history from the 1920s to the present day. I intend not to take a chronological view of this history in the way that I did with the choir’s recording history, but rather look at certain themes that characterise that history along with certain items of musical and statistical interest.

As an aperitif to Part 2 I have compiled a list of all of the radio broadcasts that I have been able to ascertain that the choir has made from 1925 to the time of writing in February 2024. In attempting to list every broadcast the choir has made on the BBC I have relied almost exclusively on the BBC’s Genome project, their online digital archive of the famous listings magazine that was first published by the company late in 1923, the Radio Times. This contains a digital transcript of every single radio listing up until 2009, including digital facsimiles of the actual pages of the magazine up until the 1950s. Thankfully 2009 coincided with my entry in the choir so I have been able to compile broadcasts from that point onwards from both the BBC Programme Index and my own records and recollections. There will be omissions, especially of any broadcasts that the choir has made away from the BBC, but the list that you will find at the end of the blog is as exhaustive as I have been able to make it. Note that I have indicated the date of broadcast for each performance. Whilst in the early days of radio this would always have been the same as the performance date as concerts could only be transmitted live, as recording technology improved so a greater proportion of performances were pre-recorded and transmitted after the event.

References:

‘The Old B.B.C. – The Story of the British Broadcasting Company, Ltd. – November 1922-December 1926’, in The B.B.C. Yearbook 1930, (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1930)

Asa Briggs, The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom – Volume I: The Birth of Broadcasting (London: Oxford University Press, 1961)

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition – A Century of Music, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

BBC Genome Project https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk

BBC Radio 3 Listings https://www.bbc.co.uk/schedules

2LO Calling: The Birth of British Public Radio, (London: Science Museum, 2018) https://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/2lo-calling-birth-british-public-radio

Roger Wilmut, Fragments of an Informal History of Broadcasting, (undated) https://rfwilmut.net/broadcast/history.html

Marconi-Sykes Magnetophone, (London: Science Museum, undated) https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8355867/marconi-sykes-magnetophone-microphone

Dalya Alberge, ‘The cello and the nightingale: 1924 duet was faked, BBC admits’, The Guardian, April 8th, 2022 https://www.theguardian.com/media/2022/apr/08/the-cello-and-the-nightingale-1924-duet-was-faked-bbc-admits

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Times Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Leave a reply to Make A Joyful Noise – The Hallé Choir on TV – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply