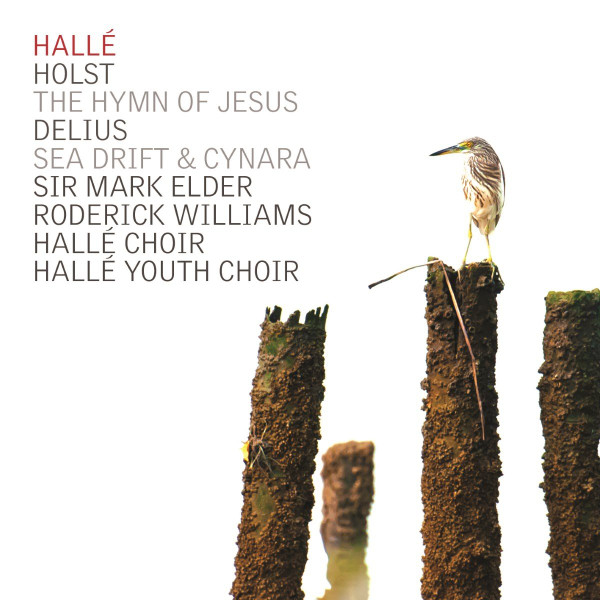

2013 Hymn of Jesus / Sea Drift

I left the story of the Hallé Choir’s recording history at the point where the choir won its third Gramophone Award out of a possible three for its trilogy of Elgar oratorio recordings under Sir Mark Elder. The next recording to be released featuring the choir showed evidence of Elder’s commitment to popularising the wider world of British music beyond the works of Elgar, a commitment that was particularly targeted this time at the works of Frederick Delius and Gustav Holst.

The two choral pieces featured on this CD, The Hymn of Jesus by Holst and Sea Drift by Delius were actually both recorded before the recording of Elgar’s The Apostles that won that third Gramophone Award, in March 2012 and March 2011 respectively, but did not see the light of day, alongside a studio recording of Delius’ Cynara for baritone and orchestra, until 2013. Both recordings, as was now the usual practice, were made up of a mixture of live performance and rehearsal outtakes, and both were also made during Frances Cooke’s time as the choir’s choral director – in terms of recordings per year in charge she is one of the choir’s most prolific directors!

Holst’s Hymn of Jesus was completed in 1919, based on texts from the apocryphal Acts of John, and in its often fervent mysticism it the work of Holst’s that perhaps most carries echoes of the Planets suite from earlier in the decade. Like Mars from that suite it also contains long passages in 5/4 time, not always the easiest time signature for choristers. The piece contains a brief plainsong introduction for male voices and a celestial-sounding female semi-chorus, and for both these the choir was joined, as forThe Apostles, by the Hallé Youth Choir under Richard Wilberforce. Two stories regarding the Youth Choir’s performance emphasise the detail that Mark Elder brought to this and other recordings.

The first concerns the initial plainsong chant. Elder wanted it to sound distant so the boys of the Youth Choir were positioned offstage. However, they were required to join the main choir for the rest of the piece so it was arranged that they should remove their shoes and walk into the auditorium in their stockinged feet to remove any unnecessary footsteps being heard on the recording. Secondly, the Youth Choir girls were positioned in the seats above the choir seats to the left of the organ in order to sound more remote and ethereal. However, Elder was not satisfied that they sounded remote and ethereal enough, so got them to sing with their backs to the auditorium into the seats behind them. Listening to the recording its obvious that both pieces of trickery worked.

John Quinn picked this up in his online review for MusicWeb International: ‘The semi-chorus is a bit more magically distanced than on any of the other recordings, yet their singing has good presence too.’ He had fine words for the choir in general as well, particularly the 5/4 section:

When the Hymn proper begins with the entry of the main choirs the music fairly blazes. Later, when Holst sets his mystic dance going in irregular quintuple metre – an inspired idea since it suggests a primitive dance, highly appropriate to the text – the performance has great spirit. The Hallé Choir sings superbly, mixing ardour and finesse as Holst’s quickly-changing musical moods demand.

John Quinn reviewing Hymn of Jesus for MusicWeb International

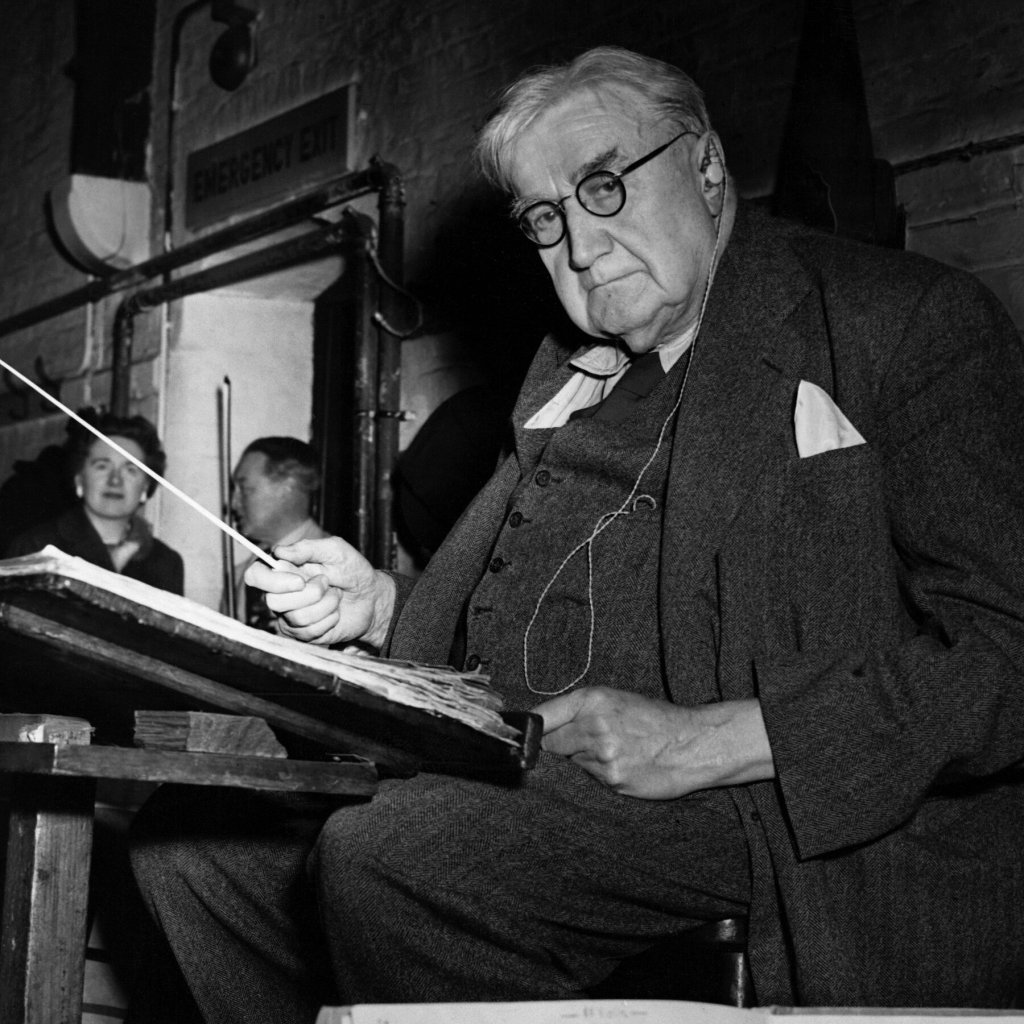

Delius’ work Sea Drift taps a wellspring that attracted many other British composers at this time, the works of the visionary 19th century American poet Walt Whitman. Particular amongst these was Ralph Vaughan Williams, who used Whitman texts in three of his major choral works, A Sea Symphony, Toward the Unknown Region, and Dona Nobis Pacem. Even today contemporary composers are drawn to the same well, for example John Adams in his work for baritone and orchestra, The Wound Dresser. There is something about Whitman’s declamatory verse style that lends itself to choral setting even as it can sound arcane when spoken aloud.

Sea Drift was written in 1903-04 for choir, baritone soloist and orchestra, and is a setting of words from the ‘Sea-Drift’ section of Whitman’s major work Leaves of Grass in which a boy’s observation of a male seabird lamenting the loss of its mate brings in wider themes of grief, loss and memory. Like Hymn of Jesus it mixes passages of quiet reflection with passages of deep emotional passion, in this work interspersed with commentary from a baritone soloist. This soloist was the inestimable Roderick Williams, in the first of three recordings he would make with the choir over the next few years.

John Quinn drew out the contrast in styles both within the piece and in contrast to the Holst recording:

The Hallé Choir, here called upon to sing very different music to the Holst, prove equally adept in this idiom and deliver Delius’s highly individual choral parts splendidly. There’s much sensitive singing from them, such as the passage beginning ‘O rising stars!’, but they do equally well when required to sing out ardently – ‘Shine,! Shine! Shine!’ being one such case.’

John Qunn reviewing Sea Drift for MusicWeb International

Andrew Achenbach was full of praise for Sea Drift in his Gramophone review: ‘…this keenly poetic, at times daringly spacious and shrewdly observant account finds Sir Mark Elder and his combined Hallé forces at the very top of their game. …this imposing Hallé newcomer deserves to be heard.’

Tim Ashley contrasted the two works succinctly in his review for the Guardian, giving the disc 4 stars and calling it ‘primarily a showcase for the Hallé Choir and Youth Choir. They’re majestic, elated and thrillingly in-your-face in the Hymn of Jesus; Sea Drift finds them more muted and subtle, rightly so.’ Piers Burton-Page in the International Record Review simply concluded that ‘the Hallé is still near the top of the league.’

2013/2021 Coronation Ode Finale: ‘Land of Hope and Glory‘

Also released in 2013 was one of a number of vintage recordings to feature the Hallé Choir that have surfaced over the last ten years. Three of these came courtesy of the Barbirolli Society, who over the last twenty years have made it their mission to add to John Barbirolli’s legacy by releasing a number of live recordings of the great conductor, most of which were originally BBC recordings.

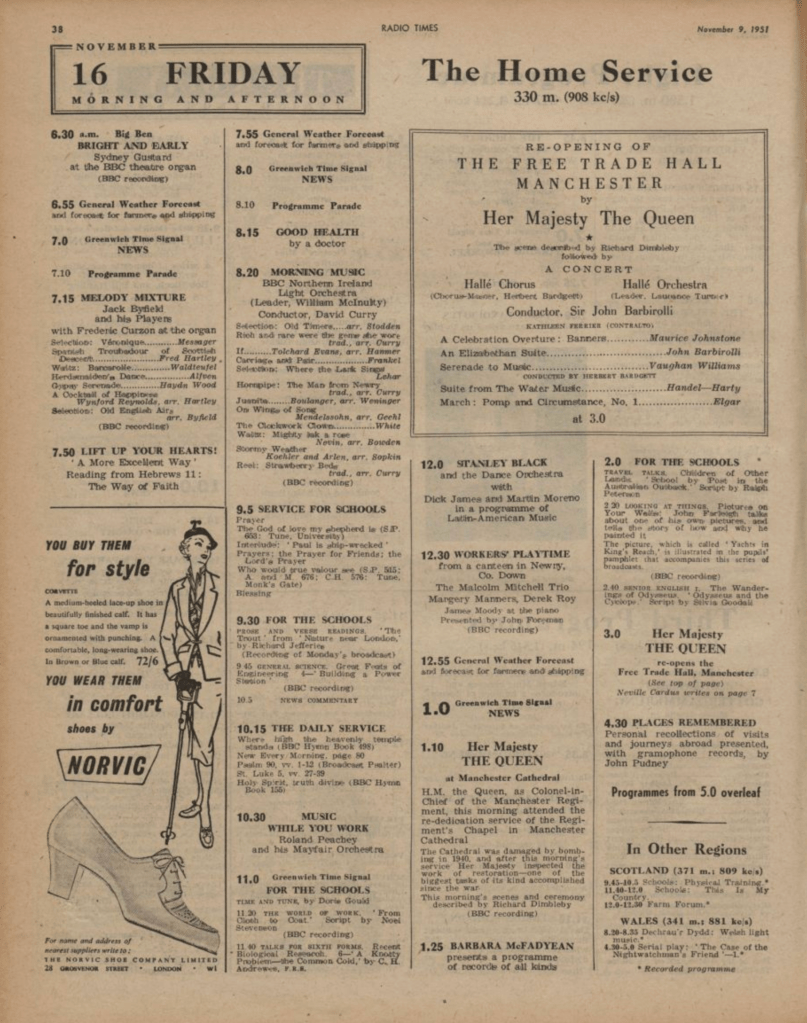

This CD was primarily a collection of major Elgar works recorded by Barbirolli between 1949 and 1956, early in his time with the Hallé Orchestra. The final track, though it only features the choir briefly and tangentially, is important for two reasons. Firstly, it was recorded in the presence of Queen Elizabeth (the future Queen Mother) on November 16th 1951, the occasion of the re-opening of the rebuilt Free Trade Hall following its destruction by German bombs during the Second World War. Secondly, it features the choir singing behind the still very much late lamented Lancastrian soprano Kathleen Ferrier. Though she sang with the choir on more than one occasion (making her debut in a performance of Messiah at Belle Vue in 1945), this appears to be the only performance that is recorded for posterity. She sang the culmination of Elgar’s Coronation Ode, a formal arrangement of the words of Land of Hope and Glory, which is very much not the Pomp and Circumstance March singalong version promised in the pages of the Radio Times (see below). She was joined at the end by the members of the choir and, as can be seen from the Manchester Guardian report of the Queen’s visit, probably a good many members of the audience too:

Then… a grand climax of Miss Kathleen Ferrier, the chorus, the orchestra, and good many of the audience singing “Land of Hope and Glory.” Here was a tribute, in superb dimensions, to many a great day in the old Free Trade Hall – a household tune of strong, direct sentiment wonderfully magnified. It was fine and it was right, but lovers of the tune will fear that never again can they hope to hear it in such glory. “There were few dry eyes” as notices of such events used to say.

Conclusion of report of the Queen’s visit to Manchester – Manchester Guardian, November 17th 1951

The recording itself is not perfect, but as a historical artefact it is both priceless and poignant, especially when one considers that in March 1951 Kathleen Ferrier had had her first diagnosis of the breast cancer from which she would die only two years later. Rob Cowan summed this feeling up in his review for the Gramophone, as he describes ‘the most wonderful account of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ imaginable with Kathleen Ferrier’ as broadly paced, beautifully enunciated and as filled with sincere feeling as you could ever hope to see.’

I will quote David R Dunsmore’s thoughts when reviewing the CD for MusicWeb International in full as they sum up in a very personal way how many still feel about Kathleen Ferrier:

The special bonus is the recording made at the opening ceremony of Free Trade Hall, Manchester on 16 November 1951 with the immortal Kathleen Ferrier. On a personal level my grandfather Tom used to hear Kathleen in a church in Blackburn at lunchtimes in the 1930s when he worked in Nelson and Colne. My aunt, still going strong at nearly 91 heard her with Bruno Walter in Edinburgh in 1947 in Das Lied von der Erde. That must surely have been a UK premiere. I heard her on the BBC Light Programme’s ‘Children’s Favourites’ about 1960. You could say she’s always been part of my musical life. This recording, acetate rumble notwithstanding, is unique and powerful… Words are totally inadequate to describe this performance. It reduces me to tears every time I hear it. Is it because it was so soon after the War with Kathleen’s death less than two years [away], the words of A.C. Benson or the tune? It’s probably a combination of the lot and the fact that I’m a huge romantic.’

David R Dunsmore writing for MusicWeb International

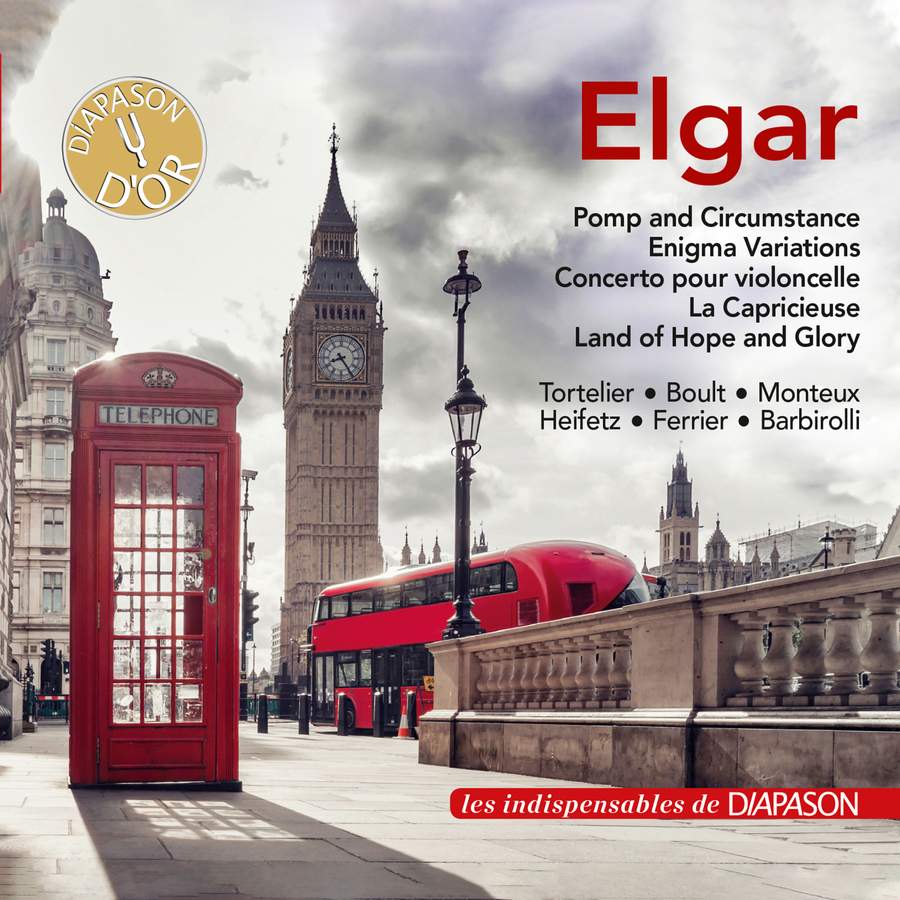

Thankfully, though the Barbirolli Society CD is not available on streaming services, the Ferrier track was included on a compilation of vintage Elgar recordings released by the French label Diapason d’Or in 2021, and as part of this compilation it is available to hear online.

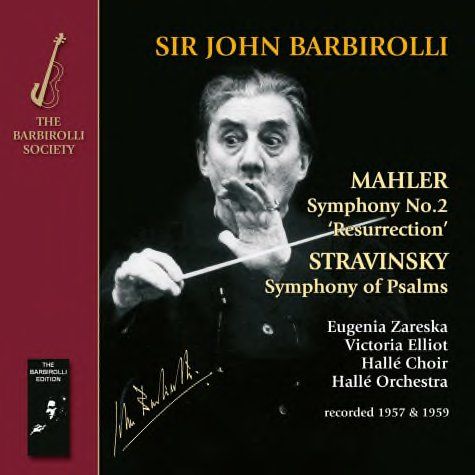

2014 – Symphony of Psalms / Resurrection Symphony

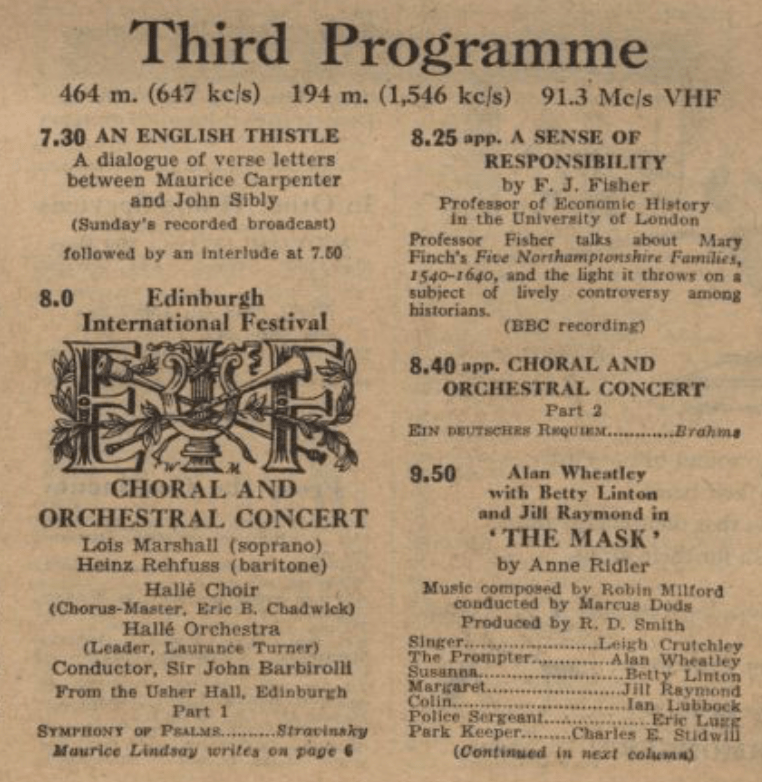

The next year saw another Barbirolli Society CD featuring the Hallé Choir, one which though it included one fabled choir story did not quite see the choir in its finest hour, at least in one of the two works on the disc. Over the years the choir have appeared a number of times at the Edinburgh International Festival, including for a performance of Dream of Gerontius in 1952 of which, given that Kathleen Ferrier was the contralto soloist, the BBC perversely only chose to broadcast Part 1, and most recently a performance of Berlioz’ Damnation of Faust in 2017 by the Hallé under Mark Elder where the tenors and basses of the choir joined Edinburgh Festival Chorus and the girls of the National Youth Choir of Scotland.

1957 saw the Hallé Orchestra under John Barbirolli play the opening concert of that year’s festival, so they were already in residency when the choir arrived for a concert on the 20th August in the Usher Hall. What was in retrospect a fateful decision was taken that rather than travelling up to Edinburgh in advance they should come up on the sleeper train from Manchester, arriving at the old Edinburgh Prince’s Street Station at 5am on the day of the concert! The story that has entered Hallé Choir legend is that even at that unearthly hour, there on the platform on a cool damp morning was Barbirolli in his trilby hat to greet them.

Whether it was the resulting tiredness from the journey or a lack of familiarity with the piece, the performance of Igor Stravinsky’s neo-classical masterpiece Symphony of Psalms that the choir opened the concert with that evening was less than inspired. Colin Mason’s review of the performance in the Manchester Guardian must be one of the most dispiriting that the choir has ever received:

They began with a performance of the “Symphony of Psalms” on which any innocent might excusably have written the work off as a perverse and incomprehensible din. Much of the fault lay with the depleted and weary Hallé Choir, which sang often wide of the notes, and with a tone as strong and clear as cotton wool. If the conductor failed in these circumstances to get the balance of chorus and orchestra right he could not really be blamed. There was no coherence of texture between choir and orchestra, nor within the orchestra itself.

Review of Symphony of Psalms by Colin Mason – Manchester Guardian 23rd August 1957

By the second half, and a performance of the Brahms Requiem, the choir had evidently regained its composure, and indeed the subheading of the Guardian review is ‘Choir’s vitality in Brahms Requiem’. However, the Barbirolli Society decided to showcase the Stravinsky performance rather than the Brahms, even though both were broadcast by the BBC. The 2014 reviewers are slightly kinder than Mason, but only just. John Quinn in MusicWeb International thought that ‘in truth, the performance they gave… is a bit variable’. Of the third movement he wrote that ‘I’m sorry to say the Hallé Choir is not quite able to deliver what their conductor wanted… The sustained notes aren’t sufficiently supported and pitching suffers as a result.’ ‘A bit variable’ and ‘not quite able’ is certainly damning with faint praise. Joseph Newsome on the Voix des Arts website, however, talked of the ‘pinpoint articulation that Maestro Barbirolli coaxes from both choir and orchestra’, though he admitted that the two recordings on the disc were ‘not performances of clinical precision, but they are pageants of the luminosity of which Maestro Barbirolli was capable.’

Listening to the recording today, it is true to say that although the first movement is sung admirably, cracks begin to appear in the slow fugue in the second movement where the choral sound descends into an out of tune mush. In the slow beginning to, and especially at the end of, the third movement the choir strive valiantly but are not helped by Barbirolli’s tempi. They sound much more at home in the fleet-footed middle section of the movement. It must be said that the orchestra sounds wonderful throughout the performance.

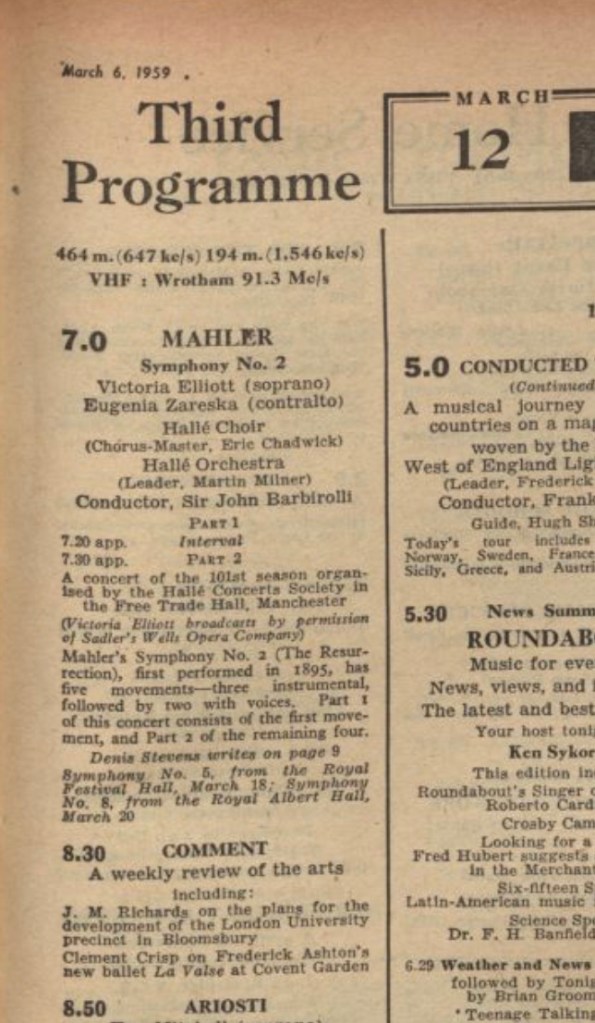

The companion piece on the CD is a performance of Mahler’s epic Second Symphony, the Resurrection Symphony with soloists Eugenia Zareska and Victoria Elliott taken from a BBC broadcast of a concert given at the Free Trade Hall on March 12th 1959. Colin Mason’s contemporary review of the concert is every bit as mealy-mouthed as his review of two year’s earlier, but this time his ire is directed more at Mahler than at the performance. Mahler’s music was at that time much more of an acquired taste than it is now. His summary of the symphony was that ‘in ninety minutes listening we have heard perhaps as much musical substance as Mozart or Schubert compresses into nine. The rest is padding, sound and fury, by which we let ourselves be hypnotised.’ His sole comment on the vocal aspects of the piece was to write: ‘The contralto song was very beautifully sung by Eugenia Zareska, and the small parts for solo soprano and chorus in the fifth movement by Victoria Elliott and the Hallé Choir.’

It has therefore been left to the reviewers of the 2014 CD to provide a more considered view of the performance. John Quinn, noting that Barbirolli never made a commercial recording of the symphony, writes that ‘Barbirolli and his Hallé forces make an excellent job of the finale… Throughout this long movement the Hallé are valiant and hugely committed… Their colleagues in the Hallé Choir make a very good contribution.’ Joseph Newsome is equally praising of the performance: ‘The nobility that the choristers bring to Klopstock’s and Mahler’s own words is captivating, and the sopranos earn special praise for the fearlessness and accuracy of their singing in the very treacherous tessitura of the Symphony’s final pages.’

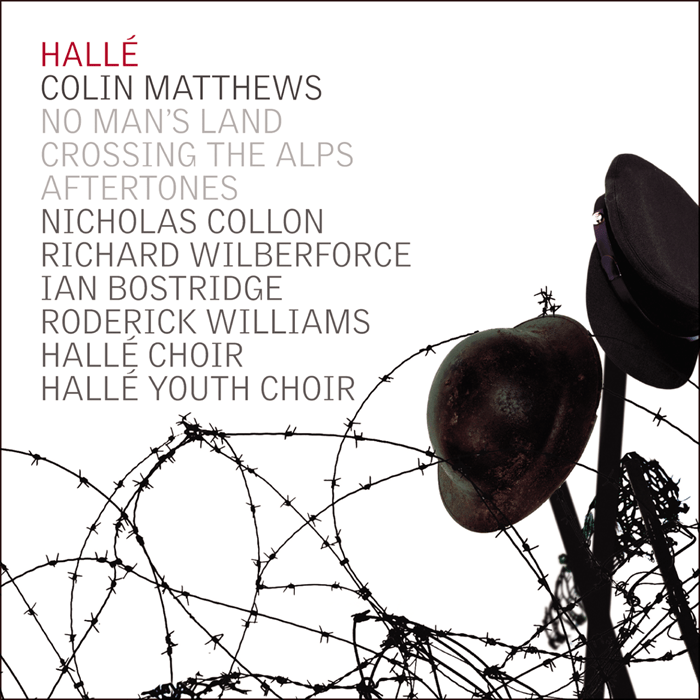

2015 – Aftertones

The recording that the Hallé Choir made over a weekend in June 2014 was noteworthy for two reasons. Firstly it was the first, and thus far only, recording that the choir has made in the new Hallé St Peter’s rehearsal and performance space, fashioned out of the Victorian St Peter’s Church in the old industrial suburb of Ancoats. Secondly, though the piece being recorded had been performed by the choir a decade earlier, this was unusually a recording not accompanied by a performance. Indeed the only time the choir sang the piece through from beginning to end during the recording process was in an initial run through – the rest was recorded piecemeal.

The piece in question was Aftertones, a setting by Colin Matthews of powerful words from one of the First World War’s less familiar war poets, Edmund Blunden. It was written for the Huddersfield Choral Society and premiered by them under conductor Martyn Brabbins in 2000, receiving a repeat performance by the Hallé Choir under Lu Jia two years later. The work was originally written for mezzo-soprano soloist and choir, but Matthews recast it for the baritone soloist Roderick Williams for the purposes of this recording. Matthews had had a long association with the Hallé, having been Associate Composer from 2001 to 2010, and the orchestra had already recorded much of his music on the Hallé label, including his Horn Concerto, a piece specially commissioned for the newly formed Hallé Children’s Choir, and his acclaimed orchestrations of the Debussy piano preludes. This was his first disc with the Hallé completely composed of vocal music, including alongside Aftertones Crossing the Alps, his setting of Wordsworth’s words that the Hallé Choir had premiered in 2010 but which here was performed by the Hallé Youth Choir under Richard Wilberforce, and No Man’s Land, a setting of an original text by Christopher Reid for tenor and baritone soloist. The resulting CD, released in 2015, formed part of the Hallé’s commemoration of the centenary of the First World War, as evidenced by the cover art.

Aftertones was conducted by the young British conductor Nicholas Collon, best known for his work with the Aurora Orchestra and a great champion of new works. This was the first time the choir had worked with him, though they worked with him on two times subsequently, both times as here on very challenging music. Though the choral writing is largely homophonic in nature, the musical language was one with which the choir was unfamiliar, and the recording process was challenging, especially given the lack of a prior performance. One particular incident remains in the memory. The choir were in the middle of successfully recording one of the more difficult passages in the piece when a flap installed to regulate air flow and carbon dioxide levels in the church very suddenly and very loudly opened, to the great amusement of all and at the cost of what would have been a perfect take. However, on listening to the recording again today, despite all the issues and coaxed by the encouraging Collon and choral director Fanny Cooke, what resulted was a powerful performance of powerful words, assisted in no small part by the passage for solo baritone that was sung beautifully by Roderick Williams.

The critics generally praised the resulting CD recording, though Richard Whitehouse in the Gramophone had some misgivings about the piece itself: ‘Both choir and orchestra manage gainfully with music whose earnest sincerity does not avoid a degree of turgidity prior to the resigned yet soulful ending.’ Fiona Maddocks brief review in the Guardian simply said that ‘the Hallé forces… give assured and committed performances.’ John Quinn’s online review for MusicWeb International was rather more forthcoming about the choir’s performance:

After the choir enters the music gradually becomes more intense and eventually a very powerful climax is attained, involving all the performers. Matthews then achieves a most satisfying close by reprising the fourth stanza of the poem set for the choir in tender, homophonic music with just the lightest of accompaniment. Aftertones was a pretty sobering musical greeting to the new millennium but it serves a wider purpose, and certainly fits well with the kind of reflection that the centenary of the Great War has provoked. I was impressed by the music and also by this strongly committed performance.

John Quinn writing about Aftertones in MusicWeb International

2015 – A Sea Symphony

Despite their long association with the composer, the Hallé had never produced a complete cycle of recordings of the symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams, that is until the arrival of Mark Elder, and a cycle that began in 2011 with the London Symphony and finally completed with the release of recordings of the 7th and 9th symphonies in 2022, the year of the 150th anniversary of Vaughan Williams’ birth. As part of my blog on the associations between Vaughan Williams and the Hallé Choir, I described in detail the process of, and reaction to, the recording of the Sea Symphony, so what follows is an expanded version of the relevant section taken directly from that blog.

The choir’s first chance to contribute to the Vaughan Williams cycle came in 2014 when a performance of the Sea Symphony on March 29th and the rehearsals that preceded it were recorded for a CD that was released a year later in 2015. In the concert the choir and orchestra were joined by soloists Katherine Broderick and Roderick Williams, the Hallé Youth Choir, the Ad Solem choir from Manchester University and the Schola Cantorum of Oxford. The choir was trained by James Burton who had been brought in by Sir Mark early on in his tenure with the orchestra to both raise choral standards and expand the choral family with the creation of the Hallé Youth Choir and Hallé Children’s Choir. He had left the choir in 2009 to pursue other interests but had been brought back as a guest director for this project.

The concert and the subsequent recording received much praise from the critics. Tim Ashley, reviewing the concert itself in the Guardian, thought the choral singing ‘had tremendous nobility, weight and elation’. The recording was shortlisted for the orchestral category in the Gramophone Classical Music Awards for 2016, losing out to Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Given the five-star reviews it received this nomination was no real surprise. Andrew Achenbach in the Gramophone praised ‘the superbly honed choral and orchestral contribution’, and Robert Matthew-Walker in Classical Source the ‘exceptional quality’ of the combined choral forces. Geoffrey Norris in the Telegraph especially praised the final movement:

The long finale – a full half-hour – is exceptionally well modulated and shrewdly paced, achieving a fusion of flow and moving intensity in which orchestral and choral colour, together with the deep expressivity and dynamism of both the baritone and the soprano Katherine Broderick, combine to attain inspiring heights.

Geoffrey Norris writing in the Daily Telegraph, August 30th 2015

Freya Parr, writing in 2019 in Classical Music, the online companion to the BBC Music magazine, compiled a list of the finest recordings of the Sea Symphony. Whilst the top award went to the fine 1968 Adrian Boult recording with the London Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra, incidentally the recording that first convinced me of the quality of the piece, the Elder Hallé recording is named as a worthy runner up alongside Vernon Handley’s recording for the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchstra and Bryden Thomson’s with the London Symphony Orchestra. Whilst, as I would, she questions Elder’s ‘broad tempos’ particular in the two outer movements, she writes that ‘the Hallé Choir is on its toes throughout’ and calls the recording as a whole ‘still a strongly stated interpretation.’

Finally, there were no fewer than three separate reviews of the recording on the online review site MusicWeb International, and though none of the reviewers rate it as their favourite (Boult’s recording again holds sway), they all rate it very highly. Ian Lace thought ‘it ranks highly with the best’, John Quinn that it is ‘one from the top drawer’, and Michael Cookson that it was ‘guaranteed to be a Recording of the Year.’

2016 – Spirit of England

The first of three recordings to be released in 2016 featuring the Hallé Choir is possibly my favourite of all the choir’s recordings, certainly of those with which I have been involved. It is a recording of Edward Elgar’s setting for choir, orchestra and soprano soloist of wartime poems by Laurence Binyon, The Spirit of England, coupled with other pieces by Elgar and Arnold Bax that link into a theme of remembrance under an overall title of ‘For the Fallen’. It is also one of only two recordings made with Madeleine Venner. I will talk about choral directors at length in a future blog, suffice to say that during her short time with the choir she made a big impact in terms of precision and attack within the choral sound, much of which is in evidence in this recording.

The Spirit of England has historically been one of Elgar’s less well-regarded choral pieces. The hints of jingoism and Empire that have always been attached to Elgar have been attached especially to this piece, though wrongly in my opinion. Yes, the Binyon poems were written in the early stages of the First World War before the full horrors of the carnage that was unfolding on the Western Front became apparent, and can therefore be seen as overly idealistic, particularly in the first poem Elgar set, ‘The Fourth of August’. However, in the way that Elgar sets the poems, particularly in his settings of ‘To Women’ and the familiar ‘For the Fallen’, and even in sections of ‘The Fourth of August’, he imbues the texts with a deep melancholy that goes much deeper than patriotic prejudice to simple heartfelt sorrow at the tragedy of war. Because of this there are certainly passages of the work that I find extremely difficult to sing because of the emotion of the moment, particularly the famous ‘They Shall Not Grow Old’ section of ‘For The Fallen’. Elder’s reading brings this sadness to the fore, making it, in my humble opinion, the definitive recording of the piece.

Though not released until 2016, the recording was actually made, using the now customary concert/rehearsal model, at the very start of the orchestra’s commemoration of the centenary of the First World War in November 2014 with Sir Mark Elder conducting and Rachel Nicholls as the soprano soloist. Also joining the choir on this occasion as associate singers were some members of the Chester Festival Chorus, who had previously sung the piece, with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra under James Burton, at that year’s Chester Summer Music Festival.

Andrew Clements reviewing the performance of Spirit of England in the Guardian, picked up the atypical nature of the piece: ‘…but in [The Spirit of England], the impressionist world of its second movement, To Women, is unlike anything else Elgar wrote, except, perhaps, parts of what survive of his third symphony.’ Writing for MusicWeb International, John Quinn homed in on a particular moment in the final, ‘For the Fallen’, movement: ‘The last few minutes of this movement, beginning at “But where our desires are and our hopes profound” constitute some of the most moving music in Elgar’s entire output.’ Comparing it with a BBC Symphony Orchestra recording under David Lloyd-Jones from 2006, Quinn praises both choirs but writes that ‘while the BBC Symphony Chorus are pretty accurate in observing Elgar’s copious markings, Elder’s Hallé Choir, expertly trained by Madeleine Venner, are absolutely scrupulous.’ In summary he praised both recordings but found that ‘Elder stirs the soul even more strongly than Lloyd-Jones.’

Jim Westhead, also reviewing the CD for MusicWeb International, was of the opinion that ‘the performance of this movement is very fine, with firm, clear choral tone and the usual great playing by the Hallé.’ He particularly liked the ‘gigantic, slow funeral march’ in the final movement ‘with the orchestra, chorus and soloist employed with vigour alternating with hushed mourning.’ Finally, Andrew Achenbach, writing in the Gramophone, called the piece ‘grievously underrated’, praising ‘Elder’s thrusting urgency in the cantata’s outer movements’. In summary, considering the CD as a whole, he wrote that ‘…this stimulating collection deserves every success.’

2016 – A Christmas Celebration

The last of the three Christmas recordings that the Hallé Choir has thus far released had a slightly elongated journey from recording to release. With the Hallé’s Associate Conductor for Hallé Pops, Steven Bell, conducting, the orchestra recorded a number of orchestra-only pieces under studio conditions in Hallé St Peters in July 2014, one month after the Aftertones recording session. The idea was that these recordings would be supplemented by live recordings taken from the Hallé’s series of Christmas concerts in the Bridgewater Hall in December of that year, performed by the orchestra along with the Hallé Choir, the Hallé Youth Choir and the Hallé Children’s Choir. This was duly done, with every second of each concert being recorded to ensure that the risk of the sound of coughing and/or errant children in the audience affecting the final product was minimised. The idea originally was to release the finished CD in time for Christmas 2015 but that deadline was missed, so the recording wasn’t finally released, as ‘A Christmas Celebration’, until October 2016, two years after the original recordings were made.

It was worth the wait however, and captures very effectively the spirit that Steve Bell and the associated musicians and singers bring to the annual Christmas concerts in the Bridgewater Hall. There is very little evidence of extraneous audience noise, except where it is absolutely appropriate in the orchestra’s traditional encore of Leroy Anderson’s jaunty Sleigh Ride, augmented here by much audience clapping along and the choirs’ obligatory slapstick impersonation. There are effective performances from both the Hallé Youth Choir, especially John Gardner’s arrangement of Tomorrow Shall By My Dancing Day, and the Hallé Children’s Choir’s meltingly sweet rendition of John Williams’ Somewhere In My Memory from the film ‘Home Alone’.

The Hallé Choir itself features on a number of tracks, such as John Rutter’s Angel Carol, Gustav Holst’s arrangement of Personent Hodie and Harold Darke’s version of In The Bleak Midwinter. The big ‘hit’ however was Adolphe Adam’s ubiquitous O Holy Night, making its third appearance in three Hallé Choir Christmas records, this time in an outrageously theatrical arrangement by one of the orchestra’s regular organists, Darius Battiwalla. Written originally for the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus whom Battiwalla directs, it has become, especially since this recording, very much part of the Hallé Christmas furniture. It’s also an arrangement that divides the choir – some love it, some hate it – but what is not in doubt is that audiences absolutely love it. There’s usually not a dry eye in the house at the end of a performance!

The CD was very well received by the critics when it finally arrived. Writing in the Gramophone, Andrew Mellor praised the recording’s professionalism, which he felt was ‘the name of the game on the Hallé’s A Christmas Celebration… even if the vast majority of the performers involved come from the orchestra’s remarkable pyramid of amateur choral ensembles.’ For him the Youth Choir won the star prize: ‘Even with massed singers, the agile performance of John Gardner’s Tomorrow shall be my dancing day gets tantalisingly close to the perfect recording I’ve been attempting to seek out for decades.’

Marc Rochester, writing online for MusicWeb International spotted the big hit: ‘Darius Battiwalla has added his own touches to a Christmas classic – O Holy Night – expanding it to almost twice its usual length while at the same time making it a wonderful showcase for the massed voices of the combined Hallé Choirs.’ He also praised the obligatory John Rutter number: ‘A Christmas CD without John Rutter is like a sea without water, and this one has his Angels’ Carol in a particularly buoyant and unsentimental performance,’ and he also praised the ‘lovely, beautifully measured and warmly expressive account of In Dulci Jubilo from the Hallé Choir’.

The recording is still very much a Christmas hit, in particular getting frequent airings in the run up to Christmas on Classic FM, and O Holy Night still brings the house down whenever it is performed at Christmas.

2016 – Messiah

In my previous blog about the Hallé Choir’s relationship with Handel’s Messiah, I talked briefly about John Barbirolli’s attempt to bring a degree of period authenticity to performances of the work, even as the choir continued to use the Prout edition based on the beefed-up Mozart orchestration. Quoting from a programme note I described how Barbirolli, whilst finding it difficult given the size of the choirs at his disposal to give performances ‘in the original’, would nevertheless like to attempt such a performance ‘some time in the future’. He also explained how he would perform certain sections, such as two choral sections, ‘O though that tellest’ and ‘Let us break their bonds asunder’ in their original setting. In 2016 the Barbirolli Society released a CD that enables to compare the Messiah performing practice of Barbirolli with the slimmed down historically informed performances that are the norm today, even when done by the Hallé.

It was a CD of the BBC recording of the choir’s performance of Messiah under Barbirolli on December 6th 1964 at the King’s Hall within the Belle Vue amusement park. As was usual on these occasions, the choir was joined by the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus (who erroneously are the only choir listed on the cover of the CD). This is significant for one specific reason – less than three weeks later the same forces would be in the Free Trade Hall for the iconic recording of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius that I described in a previous blog. Moreover, the Finnish bass Kim Borg, who would sing on the recording, was also present for this concert.

J.H. Elliot was at the concert to review it for the Guardian and, calling the Hallé’s annual Messiah performance at Belle Vue ‘an essential part of the Northern scene’, described how ‘as usual thousands made the pilgrimage’. ‘It has for some years been a ritual’, he wrote, adding ‘the trouble is that is now beginning to sound like one’. His review of the actual concert must be one of the funniest of all the reviews of Hallé Choir performances. He didn’t actually say he disliked the performance, but the way he described how Messiah was sung is somewhat excoriating to say the least, and it points up the way performances of Messiah have changed over the years. It’s worth quoting this section of the review in full, as it gets to the nub of the ‘problem’:

As a musical occasion it was many splendoured. Nor is it a bad thing to be reminded that Handel, even in so solemn a work as “Messiah,” could often be light-handed and swayed by Italian influences: or that Berlioz, even in a fit of bad temper, ought not to have described him as “a barrel of pork and beer.” There was nothing porcine or beery about yesterday’s performance. On the contrary, the prevailing characteristics were daintiness and an almost mincing precision – at any rate in those choruses, even those which amendable to grandiose effects and seem even to demand them. One does not wish for a return of the old rough-and-ready bawling, but there were many moments during the afternoon when I longed to see the choristers throw their scores over their left shoulders and sing out from their hearts. It was nice, it was musical, it was eminently agreeable, but for all the devotional feeling that was aroused the Hallé and Sheffield choirs might have been singing the telephone directory, announcing that they were going to have muffins for tea.

J.H. Elliot writing in The Guardian – December 7th 1964

Listening to the recording of the performance today on CD, one cannot help but agree with much of Elliot’s analysis. For all Barbirolli’s period sensibilities, the performance is ponderous in the extreme compared to modern recordings – many of the choruses sound like someone dragging a heavily loaded cart, particularly in the ‘Surely’ chorus which sounds never ending, and the soloists are allowed to stretch out their arias to interminable lengths. Almost everything Handel wrote, as with Bach, is essentially dance music, and there is no real attempt at any point to let the music take flight. The choral singing is mannered and safe, with little sense of drama or danger. ‘For Unto Us A Child Is Born’, for example, seems to be channelling the famous Manchester Children’s Choir ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’ recording in its clipped politeness. Having said that, one cannot help but like the recording. The choirs are in fantastic voice, and there is a simple beauty about the interpretation that transcends any stylistic quibbles. As a record of a point in time in terms of Messiah performance practices it is invaluable, and just occasionally, as with the ‘He Trusted in God’ chorus, when the choir are let off the leash there are hints of a much more exciting way to approach the oratorio. Indeed, at that point one begins to hear the choral sound that was captured so successfully in the Gerontius recording later in the month.

The CD recording was released as a limited issue by the Barbirolli Society, and I was only able to find a couple of reviews. One was by the American Brett D Wheadon, author of ‘Messiah – The Complete Guide’, an on-line site where he attempts to list, and review where possible, every recording of Messiah ever made for which audio is still available, going back to a Thomas Beecham recording from 1927. In reviewing this Barbirolli recording, he largely tended to agree with mine and J.H. Elliot’s analysis:

An historic live recording which… admirably demonstrates how far Messiah performances have evolved in performance practice over the past several decades. Every tempo is slower, grander, and richer; lines are longer, stretched out to what would be considered today indulgent lengths, and yet, nothing feels turgid or over-long – rather, this is a luscious Messiah, reveling in each moment. That’s not to say that it’s a first choice for a collection – the live sound is rather dim and compressed, especially the choral numbers, which sound positively muddy. And the performance of the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus [sic] is thick and slab-like, utterly devoid of the lightness and clarity afforded by modern choral practices… It’s good to have this performance available again – not only for its peek into historic performance practices, but for a few wonderful moments worth hearing.

Brett D Wheadon writing in ‘Messiah – The Complete Guide’

Terry Blain, writing Classical Music, was rather more succinct: ‘Heavy tempos alternate with moments of inspiration in this recording made live for BBC broadcast. The two choirs respond impressively to Barbirolli’s direction. One for specialists only.’

The recording is not available on streaming services. However, it has been made available on YouTube, so via the link below you can make up your mind whether or not you like this way of interpreting Messiah.

2019 – Nocturnes

2018 saw the centenary of the death of the impressionist French composer Claude Debussy. Mark Elder had recorded Debussy many times over his time with orchestra, including in particular premiere recordings of the aforementioned Colin Matthews orchestrations of the piano preludes. Over the course of 2018 and 2019 the Hallé recorded an entire album of Debussy’s music including the popular Nocturnes that feature a wordless female chorus in final ‘Sirènes’ section, and a group of less familiar works. These included the Première Rapsodie for clarinet and orchestra, the Marche Écossaise, a further Colin Matthews orchestration, and La Damoiselle Élue, a setting of a French translation of a poem by Dante Gabriel Rosetti for female voices and orchestra.

I talked about the 2018 Proms performance of La Damoiselle Élue in my blog about the choir’s Proms history. Shortly before that performance on July 31st sopranos and altos from both the Hallé Choir under director Matthew Hamilton and the Hallé Youth Choir under director Stuart Overington convened in the Bridgewater Hall to record the same piece under studio conditions with the same soloists as later appeared at the Proms, Sophie Bevan and Anna Stéphany. A few months earlier on April 4th the same choral forces recorded Nocturnes via the live performance/rehearsal method.

The reviews of the disc were very positive. Writing in the Gramophone, Tim Ashley called ‘Sirènes’ ‘really seductive, with ravishing string and woodwind playing and exquisite singing from the sopranos and altos of the Hallé Choir and Youth Choir,’ going on to add that ‘the choral singing similarly impresses in La damoiselle élue, particularly at the sudden, ecstatic surge of emotion as the choir contemplates the reunion in heaven of lovers separated on earth.’ Writing about Nocturnes on the AllMusic website, James Manheim wrote that ‘Elder has a precise yet dreamy way with this music, especially in the wordless chorus of Sirènes that rewards multiple hearings.’ Two MusicWeb International reviews are equally praiseworthy. Of Nocturnes, John Quinn wrote that ‘the combined upper voices of the Hallé Choir and Hallé Youth Choir make a wonderfully seductive sound while the orchestra displays great subtlety in depicting Debussy’s delicate tone painting,’ whilst of La Damoiselle Élue he wrote that ‘when the female choir enters the sound they produce is ideally chaste.’ Richard Hanlon highlighted ‘the fervent, focused singing of the upper voices of both Hallé choirs in Sirènes, and of La Damoiselle Élue he wrote that ‘Sophie Bevan makes a delightfully radiant soprano, but once again it is the focused yet glowing choral work of the Hallé choirs which most deeply touches both heart and head.’

2019 – Mimi and the Mountain Dragon

In the early parts of this blog I talked about how the Hallé Choir’s recordings moved from acoustic to electric, and then from shellac 78s to LPs, cassettes and then CDs. I also talked about how streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music became an increasingly important means of delivery alongside physical artefacts. There are actually two recordings in the choir’s catalogue that have only ever been available in digital form, either to purchase or on a subscription streaming service. The first of these was a rarity, as it is as far as I can ascertain the only appearance by the choir on a commissioned soundtrack score.

Mimi and the Mountain Dragon was an animated adaptation of the Michael Morpugo’s children’s story about a young girl from a mountain village terrorised by a fire-breathing dragon befriending a tiny baby dragon. It was commissioned by the BBC from Leopard Pictures as part of their Christmas schedules in 2019. The BBC Philharmonic were recording the soundtrack and a call went out to the Hallé for singers willing to record the song that was to close the 30 minute adaptation, and on September 24th 2019 a number of singers from the Hallé Choir, Youth Choir and Children’s Choir congregated in the BBC Philharmonic studi at MediaCity to do just that. The soundtrack to the adaptation had been written by Rachel Portman, a veteran of countless well known television and film productions, including the TV adaptation of Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit, the 1996 film adaptation of Jane Austen’s Emma for which she won an Academy Award for best score, and more recently the popular 2016 wartime drama Their Finest.

The recording session was unusual in that the orchestral soundtrack had already been recorded by the BBC Philharmonic under a bona fide Hollywood conductor in Scott Dunn. Dunn was in the studio to conduct the choir as they sang along to this pre-recorded soundtrack through studio headphones – an interesting experience. The solo introduction to the song, beautifully sung by Hallé Children’s Choir member Esther Greaves, had been recorded first, and it took quite a few takes before the choir got the hang of the process and were able to record the rest of the song, but eventually the job was done. The composer was actually in the studio to advise and comment on the performance and in a lovely touch, when the recording was complete she thanked every singer individually as they left the studio.

The finished adaptation was premiered at HOME in Manchester prior to its broadcast on Boxing Day, 2019, with Michael Morpurgo, the adaptation’s scriptwriter Owen Sheers and the original book’s illustrator Emily Gravett in attendance. The premiere was covered by Andy Murray for the Northern Soul online events guide. He reported that ‘the whole project has a decidedly northern slant, with the score being recorded at MediaCity with members of the Hallé choirs, including the singing voice of young Mimi, who was also present at the event and took a special round of applause.’ As for the adaptation itself he wrote that ”Mimi and the Mountain Dragon is a charming faux-folk tale which has a message for young viewers in these turbulent times. Only time will tell if it becomes a perennial but, do you know, it just might.’

Little did we know when watching the adaptation on Boxing Day what would befall the country, and indeed the world, a mere three months later, with the result that at the time of writing this is the last recording the choir has made, as you will read below.

2022 – Sinfonia Antartica

March 2020 saw the start of the Coronavirus pandemic lockdowns that meant the choir’s activities went on hold for the best part of 18 months. This also affected the choir’s recording schedule, with a Vaughan Williams recording that had been planned being abandoned. One Vaughan Williams recording from 2019 that did eventually emerge, however, was the choir’s second contribution to the Vaughan Williams symphony cycle that Mark Elder had started back in 2011 and to which the choir had already contributed a recording of the Sea Symphony. Once again, I’ve already covered this recording in my Vaughan Williams blog so what follows is an updated version of the relevant section of that blog.

The recording came about in January 2019, when the sopranos and altos gathered backstage with soprano Sophie Bevan to provide the wordless voices for a performance of Sinfonia Antartica, 62 years after that the choir had premiered the piece in the Free Trade Hall. As an offstage chorus behind a partly closed door, the singers apparently had to sing very loudly to sound suitably quiet and ethereal! Owing partly to coronavirus pandemic, the recording of the performance was not finally released until the spring of 2022, but like the earlier recording it garnered much praise. It was released in a 2-CD package that also included a studio performance of Vaughan Williams’ Symphony No. 9 that completed the symphony cycle, and performances of the first Norfolk Rhapsody and The Lark Ascending that were repackaged from previous CDs. At the same time a box set of all the symphonies was released, including both the Sea Symphony and Sinfonia Antartica recordings.

Andrew Achenbach in the Gramophone thought ‘…this new Sinfonia impresses by dint of its painstaking preparation, excitingly transparent textures… and powerfully evocative atmosphere’. He was less taken with the singers being placed offstage, even though this is the usual, though not universal, practice (a BBC Philharmonic performance in Bridgewater Hall during the Vaughan Williams 150th birthday celebrations in 2022 had the singers placed in the choir seats). Terry Blain in Classical Music had no issue with the positioning of the voices, writing that the Hallé’s playing mixed ‘grandeur and tragedy, with Sophie Bevan’s siren soprano and the voiceless chorus atmospherically integrated’. Likewise, John Quinn for MusicWeb International felt that in the first movement ‘Sophie Bevan and the ladies of the Hallé Choir are ideally positioned in the sound picture,’ whilst ‘at the end the female voices are again ideally distanced. The final intervention by the singers and the wind machine reminds us that the implacable Antarctic wilderness has the last word.’

2023 – Les Noces

The years since 2019 may not actually have seen the Hallé Choir undertake any new recording projects, but 2023 saw two new releases of live concert recordings, one of very recent vintage and one from rather further back in the choir’s history.

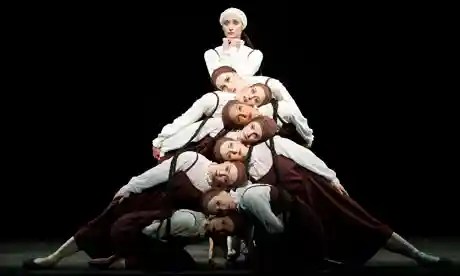

The first was the second of the choir’s recordings after Mimi to only be released in a digital form, on the new Deutsche Grammophon Verbier Festival Gold label. The choir has visited the Verbier Festival in Switzerland twice. The second was a performance the sopranos and altos of the choir gave in 2001 with a children’s choir from Prague of Mahler’s Third Symphony under the later disgraced conductor James Levine. Five years earlier in 1996 the whole choir had taken part in a performance of Igor Stravinsky’s epic, austere Les Noces with the Hallé’s then chief conductor Kent Nagano, though in Stravinsky’s idiosyncratic score the choir were joined not by the Hallé but a phalanx of percussionists and pianists and a quartet of stellar soloists. Les Noces was written by Stravinsky as the score for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev for his Ballets Russes company with choreography by Bronislava Nijinska, the sister of Vaslav Nijinsky who had provided the choreography for the infamous first performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, a recording of which is the other item on this release. In a series of scenes it tells the stylised tale of a Russian wedding, from the braiding of the bride’s hair, through the wedding itself and on to the wedding feast. 2023 marks the centenary of the first performance of the ballet, and this has been marked by performances of the ballet, both in its original form and in new choreography (for example English National Ballet premiered a new production in September 2023), and this release coincides with that celebration.

The trip to Verbier, a skiing resort high in the Swiss Alps, was quite the event for the choir. Former choir member Graham Worth remembers it well:

I was at the Verbier Festival in my second year with the choir and it was certainly memorable! I still think ‘Les Noces’ was one of the hardest pieces I have ever sung, particularly as at that time I’d had very little experience singing choral works and had gone over it so much that for months after the concert I still couldn’t get the rhythms out of my head and suffered from insomnia.

Graham Worth

As an aside, the true highlight of the festival for Graham was actually a performance of Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire for which a ‘secret’ performer had been engaged: ‘The identity of the performer was kept secret until the actual performance and I was thrilled to find that it was Björk (whom I was deeply in love with) – it was a true marmite moment but I loved every second of it.’

I find the music of Les Noces utterly compelling, as primeval and savage in its way as the much more highly orchestrated Rite of Spring, and the Hallé Choir performance on this recording is equally compelling as they drive home the chant-like choral passages with real force. This is still a relatively recent release so reviews are few as yet, but a couple of online reviews also aver to the quality of the performance. Both reviews suggested the recording is of the highest rank, such as the reviewer for Fanfare magazine who wrote:

Without sacrificing the shouting and vocal sliding occasionally called for, the singing here is mellifluous and in tune. The chorus is small enough to be intelligible, and the spirit of the vocal parts is ebullient rather than overly stylized. The piano and percussion playing is crisp and precise, captured in impeccably clear sound. One could easily make this account a first choice.

Review in Fanfare Magazine

James Manheim on AllMusic is equally effusive, calling the overall release of the two works ‘a stirring Stravinsky recording that will be welcomed even by those who have many recordings of these works in their collections’.

I would definitely recommend anyone to give this recording a listen, as I would the next, and final entry in the Hallé Choir’s recorded canon.

2023 – The Anvil

The Anvil is at the time of writing the latest Hallé Choir recording to have seen the light of day, released in October 2023. Looking through the list of choir recordings it’s astonishing to realise that, after Mimi and the Mountain Dragon, it’s only the second work that the choir has recorded written by a female composer, a state of affairs that will hopefully be rectified as the choir’s recording career nears its second century. Once again, as this work has been covered in my blog covering Hallé Choir premieres and first performances, what follows is an updated version of the relevant section from that blog.

The Anvil was commissioned by the Manchester International Festival from the composer Emily Howard to commemorate the 200th anniversary in 2019 of the Peterloo Massacre, the fateful day when mounted yeomanry stormed a peaceful demonstration in St Peter’s Fields (a site on which was later built the Free Trade Hall) causing the death of many of many of the demonstrators. It was an event that was a catalyst for the founding of the Chartists and the wider Labour movement who agitated both for a safe and humane working environment and a living wage for working people, and for the right for working people to vote.

Critical response was positive. The Times gave it four stars, praising the ‘bone-shaking force of Emily Howard’s climactic music commission’. Robert Beale, writing on the ArtsDesk website was more ambivalent, admiring the work but with reservations but wondering whether it would travel well. He did however praise Ben Gernon’s ‘sure hand on the tiller’ and thought the confident singing of the vocal forces deserved credit.

That would have appeared to have been the end of the story as far as The Anvil is concerned, but in the summer of 2023 an advertisement appeared heralding the release of the recording that the BBC had made of the performance in digital and CD form on the Delphian label, coupled with a later work of Howard’s, her Elliptics for orchestra and soprano and counter-tenor soloists. What was already a high quality radio recording has been enhanced considerably, and the new disc shows the work in all its uncompromising beauty.

Again, the release is too recent yet to have garnered a large number of reviews, but Geoff Brown in the Times gave the recording four stars, rejoicing that The Anvil is now commercially available. His review of the piece sums it up admirably:

Howard’s musical style, jangly and adversarial, entirely suits her subject, the 1819 Peterloo Massacre, where troops charged into a crowd demanding voting reforms. The soloists Kate Royal and Christopher Purves, the Hallé Choirs, the BBC Philharmonic and conductor Ben Gernon thrust us magnificently into the fray. The accompanying Howard vocal piece, Elliptics, is a little less winning, but offers more proof of a fiercely individual composing talent.

Geoff Brown reviewing The Anvil in The Times

Geoff Pearce, reviewing the piece online for from Australia for Classical Music Daily, called it ‘unashamedly contemporary music, but… one of the most original and fascinating works I have listened to in some time’. He comments on the contrasts within the piece, ‘with hymns, slogans, marching tunes, industrial sound and rapid changes of mood’ and concludes that ‘the assembled forces have done a splendid job in delivering a rather startling performance.’

Finally, as a reminder that these days of social media, reviews can be instant and pithy, there is an excellent one line review on X/Twitter by ‘The Symphonist’:

Endnote

96 years on from the first Hallé Choir recording, and despite the hiatus caused by the pandemic, there are no signs that the choir’s recording career will be abating any time soon. Recordings are planned for the coming season, and I’m sure that when Kahchun Wong takes over from Mark Elder as chief conductor at the beginning of the 2024/25 season there will be many more interesting recording projects appearing in the pipeline.

There have been a few constant threads running through those 96 years, the most obvious being the music of Edward Elgar, but what stands out most is the sheer variety of music that the choir has recorded, from cutting edge new pieces such as The Anvil and Aftertones to evergreen Christmas family favourites, and from standard choral repertoire such as Carmina Burana to decidedly niche areas like the music of W.G. Whittaker. What stands out through all of them, even those that were not originally intended for commercial release, is the commitment to excellence in all of the recording projects. Whilst critics are usually quite kind to choirs (except perhaps for J.H. Elliot when reviewing Messiah!) it is noticeable that there are very few negative reviews of any of the recordings the choir has made, and believe me when I say I have been looking for them. Long may that continue.

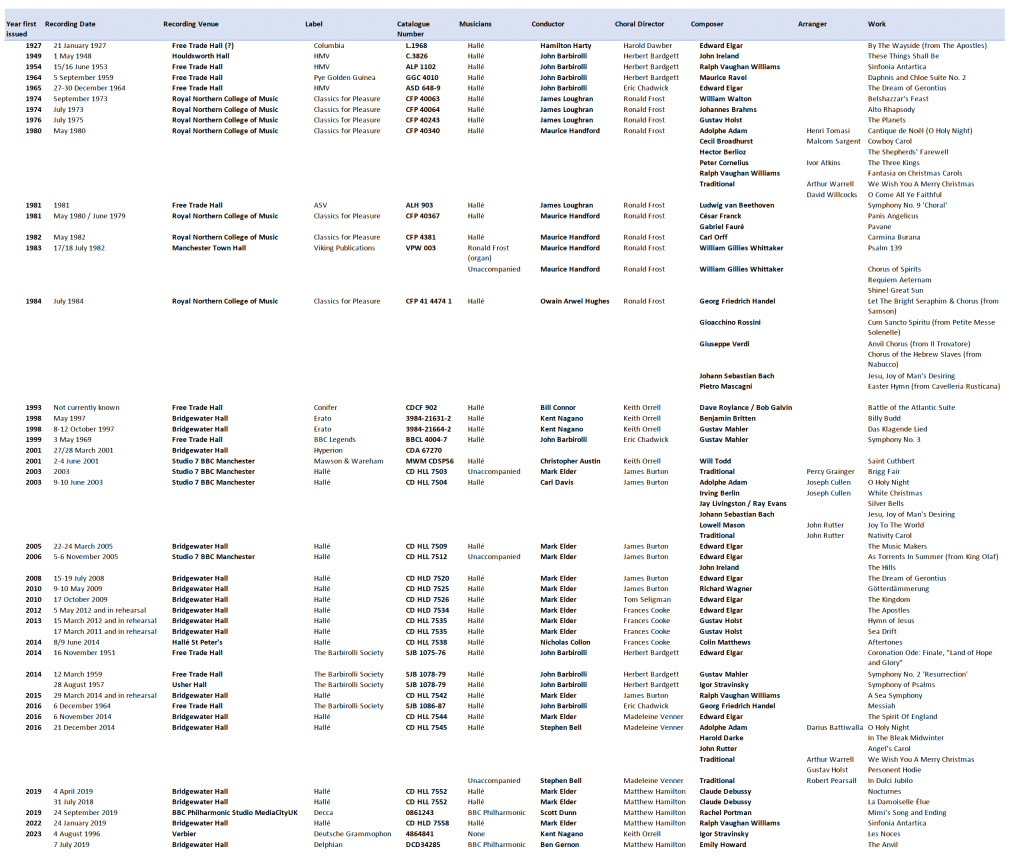

Full list of choir recordings

References

The reviews quoted are from the following sources:

Messiah – The Complete Guide https://messiah-guide.com

AllMusic allmusic.com

Classical Music Daily https://www.classicalmusicdaily.com

MusicWeb International https://www.musicweb-international.com

Fanfare Magazine https://www.fanfarearchive.com

The Gramophone https://www.gramophone.co.uk

The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/uk

The Guardian Archive via Manchester Libraries

International Record Review

Daily Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk

Classical Source https://www.classicalsource.com

Classical Music (BBC Music Magazine) https://www.classical-music.com

Northern Soul https://www.northernsoul.me.uk

The Times https://www.thetimes.co.uk

Photos and other materials from:

Wikipedia

Hallé Archive

BBC Genome Project https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk

Special thanks to Graham Worth

Leave a reply to Aufersteh’n, ja aufersteh’n – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply