Introduction

The third part of my review of the recordings that the Hallé Choir has made over the years begins in the Spring of 1999. I had intended this post to cover all of the choir’s recordings from that point up to the present day, but sheer weight of words has made me to decide to split it this period in two. This first part will therefore cover the period up to release of the CD of Elgar’s The Apostles in 2012.

At the end of the millennium the Hallé Concerts Society was not in good shape. Partly as a result of the ambitious projects undertaken by Kent Nagano, as I hinted at in my previous blog, there was a huge accumulated deficit on £1.4 million. The Guardian reported that one project alone, two concert performances of Tosca, cost the society £50,000 because they had not budgeted for the singers. Orchestra numbers were cut back and the programme for 1998/99 was deliberately conservative. Another casualty was Nagano himself, who announced in May 1999 his intention to leave the Hallé for new challenges in Berlin and Paris. The Guardian confidently predicted his successor would be Mark Elder, who at the time had no permanent position but who had been music director of English National Opera for 14 years from 1979. He had worked with the Hallé many times previously to good effect, though interestingly not during Nagano’s time in charge of the orchestra, at least until the very end of his tenure.

The prediction proved to be true when the 52 year old Elder’s appointment was announced a month later. In an interview with the Independent at the time he described how there had been hints he would join the Hallé 10 years previously, but that ‘it’s strange how it should have turned out the way it has. It’s just what I need and it’s come at just the right time.” He was to start as music director in Autumn 2000, but interestingly his first engagement with the orchestra following the announcement was a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony with the Hallé Choir in, of all places, Oldham. Elder’s final words to the Independent reporter indicate a sort of mission statement of what he intended to do with the orchestra (and what indeed he has managed to do over the last 23 years), building the orchestra and choir back up to the same stature that it had under Barbirolli. Particularly prophetic were his comments about Elgar:

This might be the time to reassert the Halle’s relationship with the centre of great English music, after a period when that’s definitely not been the case. It would be wonderful to present all of Elgar’s works instead of just the handful that are always played.

The Independent – June 7th, 1999

Elder has been true to his word with regard to English music and has taken the choir on a recording journey that has included all of the major choral works of Edward Elgar, but also rother significant works from the English repertoire by Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and Frederick Delius. All but the first of these recordings appeared on the Hallé’s own in-house label which was started in 2003. Scattered amongst these recordings there have been a number of interesting side-projects on other labels, often with other orchestras, as well as some archive recordings made available on record for the first time. This period also saw the rise of digital streaming as a common, possibly now the most common, method of delivering the music to the listening audience, and indeed two recent releases are only available in the digital format.

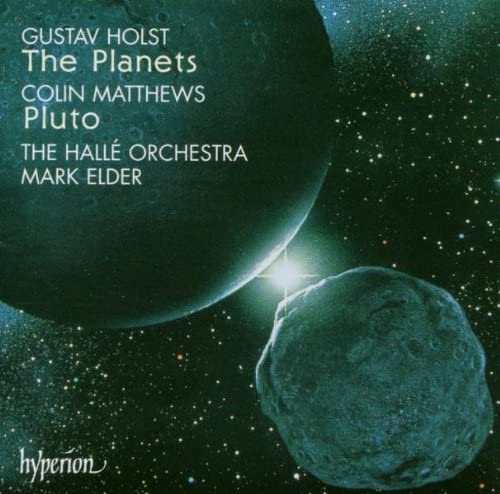

2001 – The Planets

The choir’s first recording with Elder came the year after his official start with the orchestra and was very much an oddity, being the one recording the orchestra made with the independent classical label Hyperion. Sadly it is the one Elder recording that is not currently available via streaming, though this may change now that Hyperion has been absorbed into the Universal Music group. It was a recording of The Planets by Gustav Holst and as such was also the first major work involving the choir to be recorded for a second time, following the Loughran recording that I discussed in the last blog. What makes this recording unique, however, is that it included the first recording of the Colin Matthews’ Pluto, intended as a postscript to The Planets featuring the one planet that had not yet been discovered at the time Holst wrote the suite (though there is now conjecture as to whether it actually is a planet).

Pluto had actually been commissioned by Kent Nagano, who conducted the first performance in May 2000. The way it is written it integrates seamlessly with The Planets, such that it starts before the female chorus (directed for this recording by Keith Orrell) have finished intoning their pianissimo conclusion to the final section of the suite, Neptune, and slowly emerges out of its texture. Tom Service’s review of the first performance in 2000 sums this effect up as follows:

Matthews’s Pluto emerges seamlessly from the wordless choir at the end of Neptune, who instead of disintegrating into nothingness, as Holst suggested they should, disappear into Pluto’s pianissimo and prestissimo music of scurrying but evanescent string figuration and glittering tuned percussion.

Tom Service writing in the Guardian, May 13th 2000

The integration of the two works meant that the CD recording also included a bonus track of the normal version of Neptune so that listeners could also listen to Holst’s suite as it was originally intended.

The reviews of the CD were a reasonable portent for the years ahead with Elder. Andrew Clements in the Guardian gave it 4 stars, describing how the ‘lightning-fast scherzo’ that is Pluto ‘grows out of the dying moments of the preceding Neptune and finally evaporates as mysteriously as it started’. Specifically referencing the women of the choir, Michael Scott Rohan in the Gramophone was impressed with the performance of The Planets, calling Neptune ‘surprisingly lush, a distinctly fleshly Mystic with a chorus as alluring as ethereal’. He thought Pluto ‘appealing, postmodern but lyrical, yet ultimately unsatisfying… like a spectacularly modern wing grafted onto a classic building’. Though the Observer made it one of their CDs of the week, Edward Bhesania’s review called it ‘earthbound’ and ‘unexciting’.

The choir would become more directly involved with the music of Colin Matthews, a composer with long-standing links to the Hallé, some years later, but more of that anon.

One final comment – the recording was made at the BBC Philharmonic’s rehearsal and recording studio (known as Studio 7) in Oxford Road, Manchester, as were the next few that the choir made. As we shall see, as the BBC began their move to new studios at MediaCity in Salford, so the Hallé began to explore other means of recording, namely live recordings back in the Bridgewater Hall that they had used with Kent Nagano and studio recordings in the orchestra and choir’s new rehearsal space, Hallé St Peter’s, after its opening in 2013. But again, more of that anon.

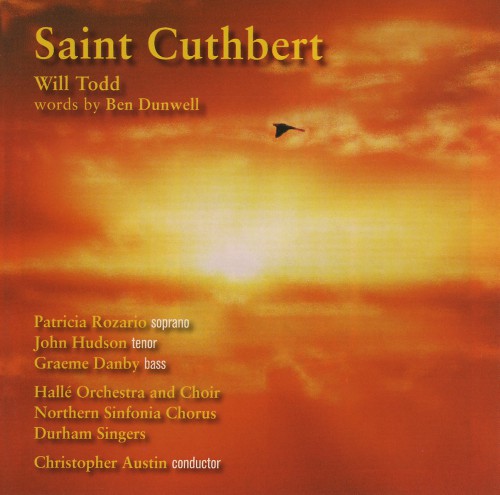

2003 – Saint Cuthbert

By 2003 Mark Elder had his feet well under the desk and was beginning to mould the orchestra and choir in the way he had been promising. The first of three CDs on which the choir appeared in that year was, however, an outside recording project dating from 2001, before Keith Orrell had been replaced as the choir’s choral director by James Burton. It was a memento of the choir’s return musically, and indeed physically, to the music of the North East of England that they had explored in their disc of the music of W.G. Whittaker. Will Todd is a choral composer perhaps best known now both for his jazz-inflected pieces such as the Mass in Blue and for his short anthems for unaccompanied choir, typified by the gorgeous My Lord has Come, which was sung to great effect by the Hallé Youth Choir at a recent set of Hallé Christmas Concerts. He has however occasionally ventured into larger-scale choral works and one such is the oratorio Saint Cuthbert.

Saint Cuthbert was written to celebrate the millennium of the Diocese of Durham in 1995 and was first performed by the Durham University Choral Society and Symphony Orchestra, conducted by James Lancelot, in December 1996. It described the life of the 7th century Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, the Anglo-Saxon monk who was sanctified for his critical role in the establishment of the early Northumbrian Christian church, and whose remains eventually found their way to Durham Cathedral. In the way it chronicles the life of the saint, via a libretto by Ben Dunwell, the work strongly resembles the structure of Benjamin Britten’s St Nicolas, even to the extent of including sections describing a storm at sea, about the saint becoming a bishop, and about plague and famine overwhelming the land, just as Britten had done. However, it must be said Britten didn’t have any passages about invading Vikings!

The piece is richly orchestrated and full of colour, though the fervour of the writing sometimes becomes a bit too portentous. Surprisingly, until the very final hymn of praise, direct references to the idioms of Northumbrian folk music are rare. The choral writing, though dramatic, is almost all strictly homophonic and never really breaks free, even though all the way through it feels it wants to.

Will Todd revisited the work in 2001 and, prior to a recording session in BBC Stuio 7 in Manchester, the Hallé Orchestra and Choir, along with their choral director Keith Orrell, made the trip up to Durham Cathedral to perform the work with the help of the Northern Sinfonia Chorus and the Durham Singers, conducted on this occasion by Christopher Austin. There was also an excellent trio of soloists, the tenor John Hudson, who would later be involved in the choir’s recording of Elgar’s The Kingdom, the bass Graeme Danby, and the charismatic Indian-born soprano Patricia Rozario, perhaps best known at that time as a frequent muse of the composer John Tavener.

To one choir member who was involved in the Durham concert, Gillian Gibson, both the location and the subject matter had a particular significance:

St Cuthbert was a special project for me. As a teenager I had spent a very happy holiday with friends, youth hostelling in Northumberland. It had enough of an impression on me that I chose to go to Sunderland Polytechnic, as it was then, where I had a wonderful time. I went up to Lindisfarne one weekend, where the story of Cuthbert caught my imagination. I went to Durham Cathedral, where Bede, Aidan and Cuthbert were very present. When our children were small our family holidays were spent in Northumberland, and our children were introduced to Cuthbert, his ducks (eider ducks are known as Cuddy’s ducks, because of them providing him with eggs and warm down whilst he was in his cave) and St Cuthbert’s Way, a long distance footpath. As if the above was insufficient for me to feel engaged to the piece, a further incentive was that our daughter caught the north east bug, and went to Durham University, to St Cuthbert’s College. She was there at the time that we performed the oratorio, in Durham Cathedral; having her in the audience of such an amazing space with such a connection was special.

Gillian Gibson

The recording session for Saint Cuthbert, with the same forces as the concert, took place between the 2nd and 4th of June, 2001. The recording was being made for the the Mawson and Wareham company, who specialise in releasing recordings of the music and comedy of the North East. Other classical recordings they have made include a series of albums of the songs of the region sung by Thomas Allen and Sheila Armstrong, but I most remember them for an offshoot label they ran in the 1970s called Rubber Records that specialised in folk rock music as well as folk comedians such as Mike Harding, who had a chart hit in 1975 (and a Top of the Pops appearance) with the legendary Rochdale Cowboy!

One of the trials of the recording process, namely the endless discussions about edits, is documented here by Gillian:

The recording was done by Andrew Keener, who ensured that every last note was as Will wanted it. At one point there was a discussion in the recording room which took about half an hour. Goodness knows what the technicalities were, but if I remember correctly we recorded about three bars after that, and were done!

Gillian Gibson

The recording was not released until the spring of 2003, but it finds the choir in exceptionally fine voice. Jill Barlow, writing inTempo magazine found much to admire in the recording, relishing the way the the drama of the music and of the libretto complement each other, and believing Todd’s vision that he laid out in the oratorio to have been ‘fully realized’. A couple of choral moments were picked out, firstly the moment in the first movement of the piece when ‘a crescendo of chorus and orchestra’ builds to a ‘cacophony of sound amidst crashing cymbals and an ecstatic “Glory to God”‘, and secondly the ‘exquisitely calm opening of the sixth movement where the choir divides into 16 parts, evoking the pull of the Tide, prefacing St Cuthbert’s death in Lindisfarne’. Lewis Foreman’s online review for MusicWeb International comments on the ‘remarkably strong forces, a large choral body, fine committed soloists and the Hallé Orchestra’ that Todd had at his disposal. His choral highlight was, like Barlow’s, ‘the wonderful calm at the opening of the sixth movement in which the chorus, now in 16 parts, evokes the pull of the tides, building to a thrilling climax’.

Though the work has not established itself in the repertoire – it’s perhaps too much of an ‘occasion’ piece to do that – the recording is still available to buy on CD via the Mawson and Wareham website (https://www.mawson-wareham.com) and can be streamed on both Spotify and Apple Music. The link to the Spotify version is found below:

The Hallé Label

2003 saw a groundbreaking move by the Hallé when they took control of their own recorded output by setting up their own ‘Hallé’ label, initially in conjunction with Sanctuary Classics. In an article in the June 2003 issue of the Gramophone, Mark Elder outlined the rationale behind the decision:

I don’t think there was any question that we could form an alliance with one of the major record companies; it would have meant recording repertoire at their insistence and their suggestion. The attraction in starting our own label… is that we can choose our own repertoire and market it in the way we want. A record label is also the simplest way to get the orchestra’s current style of playing across the concert hall barrier and into different communities and cities.

Mark Elder in the Gramophone – June 2003

He went on to echo his resolve of four years earlier to pay due regard to the music of Elgar. His first recording for the new label was to include Elgar’s First Symphony and as he said, ‘surely the orchestra that gave the world première of the piece should be recognised as the world’s premier Elgar interpreter?’. As ‘a way of re-establishing the legacy of Hallé, of Richter and of Barbirolli’ he stated his intention to ‘record all of Elgar’s music’. The Hallé Choir were not left out of his vision for the new label: ‘We have a very find choir and [a] whole new era opening there, so it’s feasible for us to record large-scale choral works’. His final words were a prophesy of how the label would actually develop:

Traditions need to be respected and appreciated but if that means dull routine it will mean death. The relationship between me and the orchestra has come at the right time and I sense that the desire for this organisation and our label to succeed is huge. I’m finding it very absorbing – and very rewarding

Mark Elder in the Gramophone – June 2003

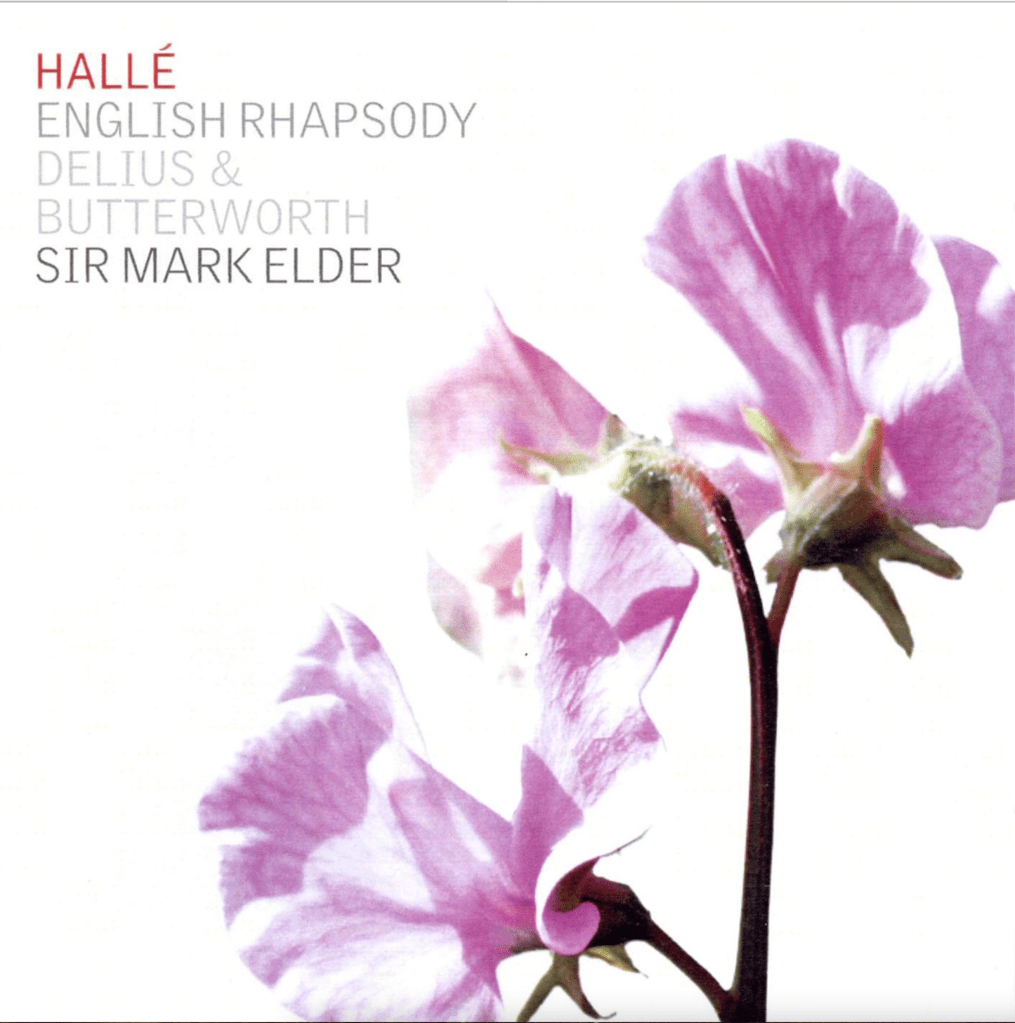

2003 – Brigg Fair

It was on the fifth of August,

The weather hot and fair,

Unto Brigg Fair I did repair,

For love I was inclined.I got up with the lark in the morning

Brigg Fair – Collected from Joseph Taylor by Percy Grainger in 1905

With my heart so full of glee,

Expecting there to meet my dear,

Long time I wished to see.

Given Elder’s promise to have his choir record ‘large-scale choral works’ it’s surprising that the Hallé Choir’s first appearance on the new Hallé label saw them singing what was very much a choral miniature, albeit a thoroughly charming one. I talked in an earlier blog about Ralph Vaughan Williams’ folk song collecting activities in the first decade of the 20th century. One of the younger collectors who followed in his footsteps was the Australian composer Percy Grainger, who wrote down the song Brigg Fair from Lincolnshire farm bailiff Joseph Taylor in April 1905 during a visit to the annual Brigg Festival. Its beautiful melody had an immediate effect on Grainger who wrote a setting of the folk song for unaccompanied chorus and tenor solo, hoping it would be performed at the following year’s Brigg Festival. The tune also inspired Frederick Delius who in 1907 wrote a short orchestral piece based around the tune and variations thereof.

It is Grainger’s version that the Hallé Choir and tenor James Gilchrist recorded on ‘English Rhapsody’, the third release on the new Hallé label. Alongside the piece, Mark Elder also conducted the orchestra in pieces by Butterworth and Delius (the above-mentioned arrangement of Brigg Fair). In a lovely touch, the choir’s rendition of Brigg Fair is followed by a digitised version of the wax cylinder recording of the song, as sung by Joseph Taylor, that Grainger made on a return visit in 1908. The Grainger arrangement is sensitively rendered by the choir, especially when they emerge from providing backing vocals for Gilchrist to take over the tune in the third verse before fading back into the background for the conclusion. A beautiful performance, and the first recording for which James Burton was choral director, having taken over from Keith Orrell the previous year. I will hopefully have more to say about both Orrell and Burton in a future blog, suffice to say for now that Burton was integral in the expansion of the Hallé’s choral offering during this decade as first the Hallé Youth Choir and subsequently the Hallé Children’s Choir joined the senior choir. Both would appear on recordings with the Hallé Choir over the following two decades.

The CD as a whole received excellent reviews when it was released in the summer of 2003, with special mention of the inspired conceit of having three versions of Brigg Fair to close the recording. Andrew Clements in the Guardian called the Joseph Taylor recording ‘a wonderful end to a wonderful disc’, and After praising the orchestra’s ‘sensitively shaded and scrupulously prepared’ reading of Delius’ Brigg Fair, Andrew Achenbach in the Gramophone praised the ‘imaginative programming’ that ‘allows us to sample Percy Grainger’s ravishing 1906 setting of the same Lincolnshire folksong (stylishly given by tenor James Gilchrist and the Hallé Choir) as well as a 1908 recording made by 75-year-old Joseph Taylor’.

2003 – Christmas Classics

The third recording released in 2003 to feature the Hallé Choir has particular poignancy at the moment given that its conductor, Carl Davis, died earlier this year at the age of 86. New York-born Davis spent most of his career in England. As a composer he specialised in writing scores for film and television, most notably the famous 1995 BBC adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. However, he also wrote a number of concert works and ballet scores and gained particular fame in 1991 when he collaborated with Paul McCartney on McCartney’s Liverpool Oratorio, written to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society. Though he indeed collaborated many times over the years with the RLPO, he occasionally came across to Manchester to work with the Hallé, and this recording was the result of one such visit.

It was the second of three Christmas albums that the Hallé have released over the years following on from Maurice Handford’s recording of 1980. Like that album it included a mix of orchestral and choral Christmas favourites, with the added attraction of Claire Rutter’s soprano voice on a number of the tracks. It included two numbers that have become synonymous with Hallé Christmas concerts over the years, namely Leroy Anderson’s Sleigh Ride (though this version doesn’t have the now standard obligato part for choir handclaps!), and Adolphe Adam’s popular O Holy Night, which had also appeared on Handford’s disc and would appear on the orchestra’s next Christmas CD a decade later. Other tracks featuring the choir included John Rutter’s beautiful Nativity Carol, Lowell Mason’s rousing Joy to the World, and an arrangement for soprano and choir of Irving Berlin’s timeless White Christmas, where the choir go full Hollywood! There was also an extract from the Liverpool Oratorio featuring boy treble Eric Traulert. This was shortly before the foundation of the two choirs that would become such a feature of Christmas with the Hallé, the Hallé Children’s and Youth Choirs.

Current members of the choir who sang on this recording remember Davis as not being the easiest man to deal with. Phil Hilton remembers his reaction to some of the choir trying, given the recording took place in BBC Studio 7 in June 2003, to recreate the spirit of Christmas in summer:

I remember Carl being a little cantankerous as many of us put on our Christmas hats for the recording and he immediately ordered us to remove them as such things were not considered ‘professional’.

Phil Hilton

Malcolm Riley’s review of the CD in the January 2004 issue of the Gramophone alludes to the revival in fortunes under Mark Elder when, after reviewing an RLPO Christmas CD, he writes: ‘Tracing the Mersey upstream to Manchester brings us to the rejuvenated Hallé Orchestra and Choir directed by Carl Davis’. He very much enjoyed the recording too: ‘Soprano Claire Rutter tops off a vibrant and warm-blooded choral sound. The recording quality, too, is absolutely first-class’.

2005 – The Music Makers

By 2005, as part of his mission to reconnect the orchestra with its Elgar heritage, Mark Elder had already conducted the choir in recordings of Elgar’s two symphonies, the Enigma Variations and the Cello Concerto. It was high time to start exploring the choir’s Elgar heritage, and the first fruits of that exploration came not with one of the big oratorios – their turn would come later – but with one of Elgar’s relatively less well-known choral works, The Music Makers, written for the Birmingham Festival of 1912 where the choir was trained, of course, by R.H. Wilson. This piece is a personal favourite of mine, but it does have its detractors, such as the man who reviewed the choir’s performance of the piece in the Free Trade Hall in February 1929: ‘Elgar’s “The Music Makers” was well enough sung, but in the end it left us not a little weary. The music’s chief interest is the expert way Elgar quotes himself from greater works than this’. For me that is part of the attraction, as Elgar sets O’Shaugnessy’s rather hackneyed ode to music and those who create it by interspersing much beautiful original music with choice quotes from his own music making, from Enigma Variations and the First Symphony amongst others. There is also a deep sense of melancholy in much of the music. Written as it was shortly before the First World War and at a time when Elgar’s Catholic faith, so strong when he was writing the three big oratorios at the beginning of the century, was wavering, it almost feels like a premonition of the sadness that would infuse both the wartime Spirit of England and the post-war Cello Concerto.

It also must be said that the work is very much a choral tour-de-force, as apart from a few short passages where the mezzo-soprano soloist sings alone, the choir sings for all of its 38 minute duration, making it Elgar’s longest through-written choral work. The choir are very much up to the task, showing evidence of the care and attention James Burton had put into developing the sound of the choir. His arrival had been followed by a radical re-auditioning of the choir, from which it took the choir time to rebuild in terms of numbers and sound, and this recording shows the process was nearing its completion, with the choir seemingly gaining in strength as the work progressed, ably assisted by the rich vibrato of soloist Jane Irwin.

Recording sessions took place in the Bridgewater Hall in March 2005. The resulting CD, entitled ‘Elgar – A Self Portrait’ and also including the Froissart overture, Dream Children, and Elgar’s orchestration of Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in C Minor, was released later that year to good reviews. Edward Greenfield, writing in the Gramophone, called it ‘another excellent instalment in Mark Elder’s Elgar series’. As far as Music Makers is concerned he saw the ‘full-ranging recording’ as ‘bringing out the subtlety of Elgar’s orchestration’. He preferred Janet Baker in the Adrian Boult recording to Jane Irwin’s ‘much lighter mezzo’, but praised the ‘crisp ensemble’ of the choir directed by James Burton’. Andrew Clements in the Guardian gave the recording five stars. He had high praise for The Music Makers, ‘wonderfully presented by Elder’ with Irwin and the choir making ‘eloquent sense of its patchwork of thematic self-references’, and managing ‘to create a genuine creative testament out its setting of Arthur O’Shaugnessy’s aspirational verses’. Finally, Gwyn Parry Jones’ online review for MusicWeb International found the recording of the piece to be revelatory, with Elder’s ‘grasp of the work… more comprehensive than any of his rivals on disc’ with key moment being ‘the tingling, reckless [Elder] brings to the passage that begins “And therefore today is thrilling” – this is Elgar at his greatest, and Elder and his forces rise to the challenge magnificently’.

2006 – As Torrents in Summer / The Hills

As well the recording of The Music Makers, as I described in my blog about the Hallé Choir and the Proms, 2005 also saw Mark Elder conduct the Hallé Choir and the recently formed Hallé Youth Choir in a landmark performance of The Dream of Gerontius at the Royal Albert Hall that was broadcast live on BBC 4, thus bringing Elder’s Elgar project to a much wider audience.

However, the Hallé Choir’s next CD project was not Gerontius as might have been expected – that would wait for another three years – but the recording of two unaccompanied partsongs in BBC Studio 7 in November 2005, one by Elgar and one by John Ireland. Elgar’s As Torrents in Summer started life as part of the epilogue of his now largely neglected choral cantata King Olaf (or Scenes from the Saga of King Olaf to give it its full name) with words by Longfellow, but is now much better known by choirs as a stand-alone partsong. Ireland’s The Hills, with words by James Kirkup, was written in 1953 as part of a set of 10 partsongs by 10 different composers to words by 10 different poets compiled to commemorate Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in 1953. Both works are beautifully sung with clean and precise textures, not always easy when such a large choir sings unaccompanied, and show further evidence of the progress the choir was making.

The recordings were released in 2006, forming the coda to a CD entitled ‘English Landscapes’ that comprised various quintessentialy English works such as Tintagel by Arnold Bax, The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams featuring the Hallé’s leader Lyn Fletcher, and Frederick Delius’ Two Pieces for Small Orchestra.

The CD did not evoke a particularly positive response from Andrew Achenbach, writing in the Gramophone. In terms of the orchestral recordings, he saw it as ‘a disappointment, immaculately played to be sure but the comparatively analytical sound balance robs the music of romantic glow and elemental spectacle’. However, he did concede that ‘the Hallé Choir is in fine fettle for the two a cappella items by Elgar and Ireland that conclude what is on paper an attractive programme’.

However, Andrew Clements in the Guardian was more impressed, giving it four stars and concluding that ‘all of the performances are perfectly judged and the orchestral playing is predictably first rate’ and giving a special mention to ‘two pieces that give the Hallé Choir their moment in the spotlight’.

2008 – The Dream of Gerontius

2010 – The Kingdom

2012 – The Apostles

I just remember the last strains of the music dying away, and normally at the end of a recording everyone is tired, and pootles out chatting to friends. Not this time! There was a hushed awe around the room, with a feeling of ‘what just happened?’

Gillian Gibson talking about the Gerontius recording in 2008

When musical historians of the future come to assess Mark Elder’s music directorship of the Hallé, I would like to believe that they will come to think of the recordings of Edward Elgar’s three great oratorios, The Dream of Gerontius, The Kingdom and The Apostles, that he undertook between 2008 and 2012 as the pinnacle not just of his time with the Hallé Choir, but of his time with the orchestra. This is notwithstanding his other great achievements, such as his complete Ring Cycle recordings and his acclaimed complete Vaughan Williams symphony cycle. They were the culmination of his avowed mission to champion the music of Elgar and through so doing reconnect the orchestra with its great Elgar interpreters of the past, particularly Hans Richter, who worked directly with Elgar on all three oratorios, and John Barbirolli, who created what many still consider to be the definitive recording of Gerontius.

It is also probably no coincidence that the first oratorio (though Elgar never liked calling Gerontius an oratorio) was recorded in 2008, 150 years after Charles Hallé first conducted the orchestra that now bears his name. Elder acknowledged that heritage in an interview Martin Cullingford for the Gramophone:

From the example that [Hallé] set, I feel a terrific sense of contact with what he came here to achieve. I feel a connection with the sense of tradition that he inaugurated here 150 years ago, because he grabbed the opportunity completely unexpectedly to come and bring music to a community that didn’t have it.

Mark Elder quoted in the Gramophone, February 2008

What better way therefore to honour that tradition than to record a composer who was very much a signifier of that tradition. I will cover these three recordings together as I feel they deserve to be treated as a single entity. Three recordings, three award winners, but interestingly undertaken with three different choral directors.

The first recording was of Gerontius, so successfully performed at the Proms three years earlier. Elder retained two of the cast from that performance, Paul Groves and Alice Coote, but for this recording Matthew Best was replaced by the acclaimed Welsh bass-baritone Bryn Terfel. Elder also stuck with the admirable conceit of having the Hallé Youth Choir sing the semi-chorus in what would be their debut recording as a choir. Andrew Keener was the producer for the recording sessions which took place between the 15th and 19th of July 2008 under studio conditions in the Bridgewater Hall. Both choirs were prepared by James Burton who had helped found the Hallé Youth Choir in 2003. Judging by choir member Gillian Gibson’s recollection at the beginning of this section, the spirit in the room must have been very similar that felt by the Hallé and Sheffield choirs in the Free Trade Hall back in December 1964 when Barbirolli was making his legendary recording of the oratorio. History was not so much being written as being re-written.

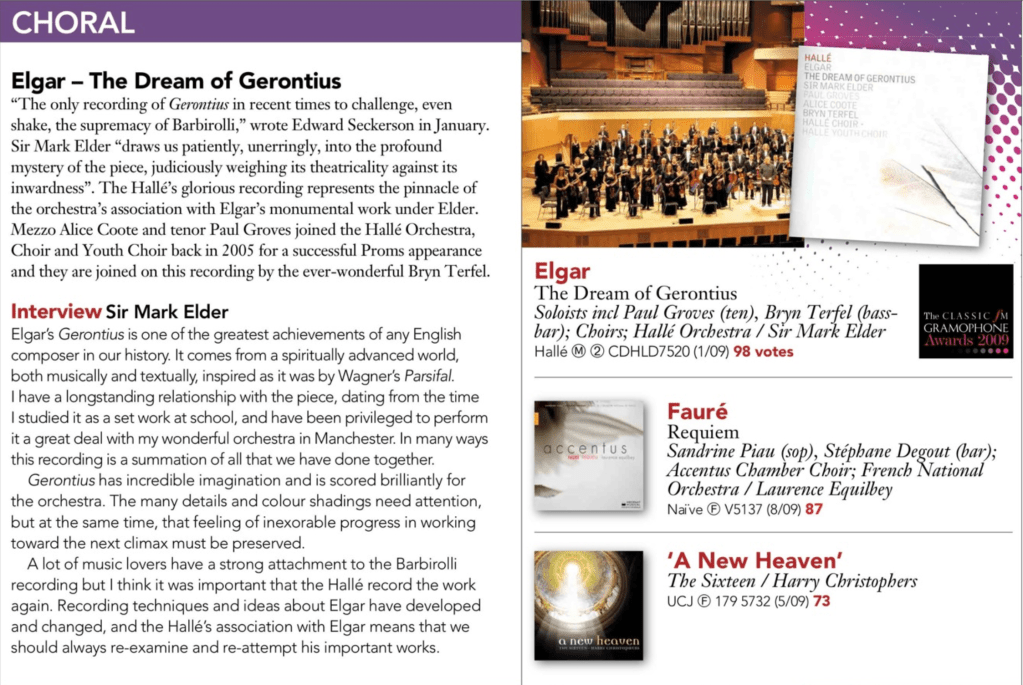

The reviewers obviously sensed this when the resulting CD was released at the end of the year, as evidenced by the headline of Edward Seckerson’s review in the January 2009 issue of the Gramophone – ‘Bryn Terfel joins a near-perfect Gerontius in Paul Groves for a heavenly performance’. In the review itself, he made the inevitable comparison to the Barbirolli recording with his opening comment that ‘it is only fitting that the Hallé should be the source of the only recording of Gerontius in recent times to challenge, even shake, the supremacy of Barbirolli’. He described the ‘fine and most satisfying recording’ as ‘the best-sounding Gerontius we have had, handsome in its depth and breadth with great spatial perspectives and a wonderful sense of how the score is layered’. Acknowledging the shadow of Janet Baker he had kind words for Alice Coote’s ‘highly personalised reading’ of the Angel and for Paul Groves’ ‘near-perfect blend of poetic restraint and high emotionalism’ as Gerontius. In all the praise he rather forgot the choirs, the only mention being with regard to the ‘Praise to the Holiest’ section: ‘The Hallé choirs bravely gather momentum in that, thanks to Elder’s insistence on clear rhythmic articulation, and he achieves a simply stonking crescendo on the final chord, leaving the organ to plumb infinite depths’.

Andrew Clements five-star review in the Guardian was equally effusive. Again there are comparisons with Barbirolli – Elder’s recording may lack the ’emotionalism’ of Barbirolli, but ‘both take full account of the score’s blazing theatricality’. For Clements ‘the orchestra and chorus are wonderfully imposing’, and in his final comment he expressed amazement that ‘a singer of [Bryn] Terfel’s class is just one element of a quite remarkable all-round achievement’. Of the online reviews, of which by 2008 there were an increasing number, Gerald Fenech on Classical Net is typical: ‘The Hallé recording is quite flawless with fine balance between orchestra, soloist and chorus as after all is to be expected from this excellent source’. This excellence was recognised when in the Gramophone Awards of 2009 the CD one the prize for best choral recording of the year.

It is at this point that I should note the beginning of my personal connection with the choir, as I joined the Hallé Choir in the autumn of 2009. From this point onwards I hope the reader will forgive me occasionally giving my own personal recollections of the new recordings that followed. I actually sat in on the first rehearsal for the choir’s performance of The Kingdom that formed the basis of the next instalment in the Elgar trilogy, but because of other choral commitments I was unable to sing in the concert, to my eternal regret.

James Burton had left the choir in the summer of 2009 following a highly successful period in charge which had seen the choir reach new levels of excellence and had also seen a growth in the Hallé’s choral offering with the formation of the Hallé Youth and Hallé Children’s Choirs. In attempting to find a replacement for Burton, various guest choral directors were engaged through 2009 and 2010, the first of which was Tom Seligman, who was given the job of preparing the choir for The Kingdom. Seligman had worked with the London Symphony Chorus and with choirs at the Lucerne Festival but has since become better known as a ballet conductor working with companies such as the Royal Ballet and New York City Ballet.

In terms of recording this project broke new ground for the choir. Rather than making the entire recording under studio conditions as had previously been the norm, either in the Free Trade Hall, Bridgewater Hall, the RNCM or a BBC Studio, the decision was taken in conjunction with producer Steve Portnoi to base the recording on a live performance of the piece in question in front of an audience. In order to provide patches to cover extraneous audience noise or choral and orchestral errors both of the prior orchestral rehearsals would also be recorded to provide material for those patches. This has become the model for most choir recordings going forward, though occasionally there have been formal patching sessions following the live recording.

Elder assembled another excellent cast of soloist for the live performance, soprano Claire Rutter and tenor John Hudson, who had both worked with the choir on previous recordings. mezzo Susan Bickley, and finally baritone Iain Paterson, who would work with the choir many times over the following years.

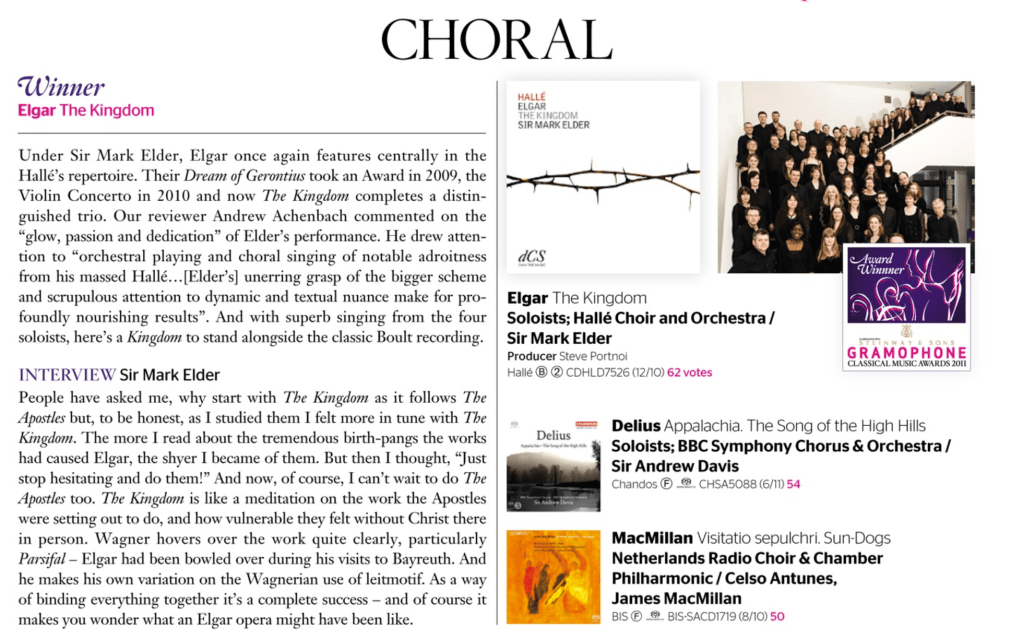

When the reviews of the subsequent CD appeared late in 2010, one review at least suggested that the new method of recording had been a success. Andrew Achenbach in the Gramophone was of the opinion that ‘producer/engineer Steve Portnoi can be proud of the spectacular range, opulence and realism of his efforts’. He was impressed with the sheer depth and detail of the recording:

Not only does [Elder] draw orchestral playing and choral singing of notable adroitness from his massed Hallé forces (the violins perhaps lacking something in sheer opulence), his unerring grasp of the bigger scheme and scrupulous attention to dynamic and textural nuance make for profoundly nourishing results.

Andrew Achenbach writing in the Gramophone, December 2010

John Quinn’s online review for MusicWeb International concurred, believing the new recording, though behind Adrian Boult’s in terms of its soloists, to be the ‘pre-eminent digital account’. The choir received special praise – ‘from the very start they sing with great confidence and impressive tone’. He also praised their dynamic range from very loud to very soft, as a well as their clarity of diction, summarising the choir’s contribution as ‘first-class’. However, Andrew Clements in the Guardian was less impressed, giving it only three stars, though reading between the lines you get the impression that his main problem is that he thought The Kingdom a lesser work than its predecessor: ‘The Kingdom stems more from the Victorian oratorio tradition indebted to Mendelssohn and Stainer, which Elgar never quite transcends’. He does however conceded that ‘the best moments… are superbly done, as are the great choral outpourings’. As a whole though, ‘it remains subdued, never sparking into dramatic life’.

The question following the CD release was whether it could repeat the success of the Gerontius recording in the Gramophone awards. Given its mixed, even if largely positive, reception its prospects were uncertain. Any doubts were removed, however, when the 2011 Awards issue announced that once again, against strong opposition, the Hallé had won the choral category.

I have already talked in a previous blog about the performance of Elgar’s The Apostles that the Hallé Choir gave at the BBC Proms in 2012, and about how, using Elgar’s own precedent, Mark Elder cast nine individual singers from the RNCM as the nine non-named apostles in the piece, even though they are normally sung as a tenor/bass semi-chorus. I also talked about the excitement of performing in London in the midst of the London Olympics, with the open water swimming race taking place in the Serpentine as we were assembling for our afternoon rehearsal. What I did not mention that concertgoers were presented with the option not just of buying a programme for the concert but also of buying a CD of the very work being sung. This was the recording of The Apostles that the choir had made only three months earlier in the Bridgewater Hall, rush-released in order to make it available to Promenaders.

What purchasers got was a recording made using the same method as The Kingdom, with the bulk of the content coming from the concert performance in the Bridgewater Hall on May 5th, but with patches from the rehearsals over the previous couple of days. What they would hear in the Prom was almost exactly the same cast of soloists as had appeared on the recording, the only exception being Brindley Sherratt, who was replaced for the Prom by Clive Bayley. So they would have heard Jacques Imbrailo’s clear-toned Jesus, and an impassioned Mary Magdalene from Alice Coote, who with tenor Paul Groves was returning after their appearance in the Gerontius recording. Whilst memories of the Manchester concert remain hazy compared to the Prom, one memory that does remain is of the excellence of the Hallé Youth Choir who once more sang the semi-chorus passages, in particular the chorus mysticus that illuminates the final pages of the oratorio.

As hinted at above, this recording also saw another change of choral director. After various guest choral directors had been trialled following the departure of James Burton, further auditions resulted in the appointment of Madeleine Venner as the new permanent choral director. For various reasons she was unable to take up the post immediately so it fell to Frances Cooke, the choir’s long-standing associate choral director to take on the job of training the Hallé Choir, with Richard Wilberforce training the Youth Choir. Fanny had experience in preparing large forces, having been in charge for performances of Mahler’s monumental 8th Symphony in Manchester and Birmingham a couple of years earlier. As I remember it, the rehearsals for The Apostles were, as usual with Fanny, a joyful experience.

The CD that resulted suffered not at all from the speed with which it had been released. Andrew Achenbach, writing again in the Gramophone, called it ‘a set absolutely not to be missed’, writing that ‘Sir Mark Elder and his Hallé forces continue to set stellar standards in large-scale Elgar.’ (Note the ‘Sir’ Mark – Elder had been knighted in June 2008 in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List.) This passage from Achenbach’s review is worth quoting in full:

Not only does Elder obtain playing and singing of the utmost accomplishment and sensitivity, his hugely penetrating interpretation evinces an idiomatic pliancy, sure dramatic instinct and iron grip (the magnificent final climax to ‘The Ascension’ has a giant inevitability about it), as well scrupulous fidelity to both the letter and spirit of the score.

Andrew Achenbach writing in the Gramophone, November 2012

Edward Seckerson, writing in the Gramophone in December 2012 felt glad that his feelings that this work was the weakest of Elgar’s trilogy were ‘so dramatically reversed by Mark Elder’s compelling advocacy’. Andrew Clements in the Guardian liked the recording quality – ‘it’s hard to believe that this detailed account was sourced from a concert’ – and obviously liked it more than The Kingdom as this time he gave it four stars!

Excitement obviously grew in the run up to the Gramophone Awards of 2013. Would the Hallé make it a hat trick of choral awards for Elgar recordings? In the end there was little doubt as The Apostles won the award by a wide margin. A final postscript – in June 2023, in advance of the choir singing all three of these oratorios over the course of two weekends and in preparation for Mark Elder’s final season as music director of the Hallé, the three recordings were re-issued in a single box set.

2010 – Götterdämerung

Also released in amongst the Elgar oratorios was a bumper 5-CD recording of the choir’s one contribution to Mark Elder’s mission to record the whole of Wagner’s Ring Cycle with the Hallé, namely Götterdämerung, the last opera in the cycle, first performed in 1876 with Hans Richter as the conductor. The opera is so vast that the performance during which the CDs were recorded was spread over two evenings in May 2009. Joining a star-studded cast was a monumental choir which along with Hallé Choir featured members of the BBC Symphony Chorus, the London Symphony Chorus and the Royal Opera Chorus.

As one would expect a massive sound was achieved which received an equally massive response from the audience at the concert, as evidenced by the eight minutes of applause at the end of the final CD. That response was echoed by Mike Ashman who reviewed the recording for the Gramophone and called it ‘the most compelling and best-cast Götterdämerung on disc since Barenboim’s from Bayreuth’. He praised the recording quality which ‘plays to, or has used, the hall and the performance well, accommodating the large full chorus’. Andrew Clements review in the Guardian was less full-throated. Referencing the eight minutes of applause he writes that ‘what evidently worked so well in concert does not always transfer convincingly to disc’. However, though he had praise for Elder and his orchestra and the way he shaped and paced the performance, there were deficiencies in the singers in the three main roles that he could not overlook.

What remains, however, is an interesting sidenote in the recording history of the Hallé Choir. Nothing quite like had been released before and nothing quite like it would be released after. It concludes the first half of my survey of choir recordings released during Mark Elder’s time with the Hallé. In my next blog I will resume the story with the release in 2013 of two English choral gems, Delius’ Sea Drift and Holst’s Hymn of Jesus.

References:

Lynne Walker, ‘They call him `the Ayatollah’, The Independent, June 7th 1999 https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/arts-they-call-him-the-ayatollah-1098852.html

John Ezard, ‘Nagano passes on Hallé baton’, The Guardian, May 25th1999 https://www.theguardian.com/uk/1999/may/25/johnezard

‘Brigg Fair (Roud 1083)’, Mainly Norfolk https://mainlynorfolk.info/joseph.taylor/songs/briggfair.html

’50 Years of Music and Comedy from the North East’, Mawson and Wareham www.mawson-wareham.com

Reviews, interviews and adverts from the following online sources:

The Guardian www.theguardian.com

The Gramophone www.gramophone.com

Tempo Magazine

MusicWeb International www.musicweb-international.com

Classical Net www.classical.net

Thanks to the choir members who contributed

Leave a reply to On Air – The Hallé Choir and Radio: Part 2 – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply