Introduction

Continuing the story of the Hallé Choir’s recording history, the years between John Barbirolli’s death in 1970 and Mark Elder’s appointment as music director in 1999 were not always the most successful years financially for the Hallé Orchestra, but as far as recordings were concerned it was a fruitful period. Many of the recordings the orchestra made during this time were on budget labels, thus bringing the orchestra to the widest possible listening audience. As far as the choir was concerned, this period also saw what was probably their most eclectic in terms of repertoire, ranging from Beethoven and Brahms to the unaccompanied choral music of Newcastle composer W.G. Whittaker, and from Britten and Mahler to the Cowboy Carol.

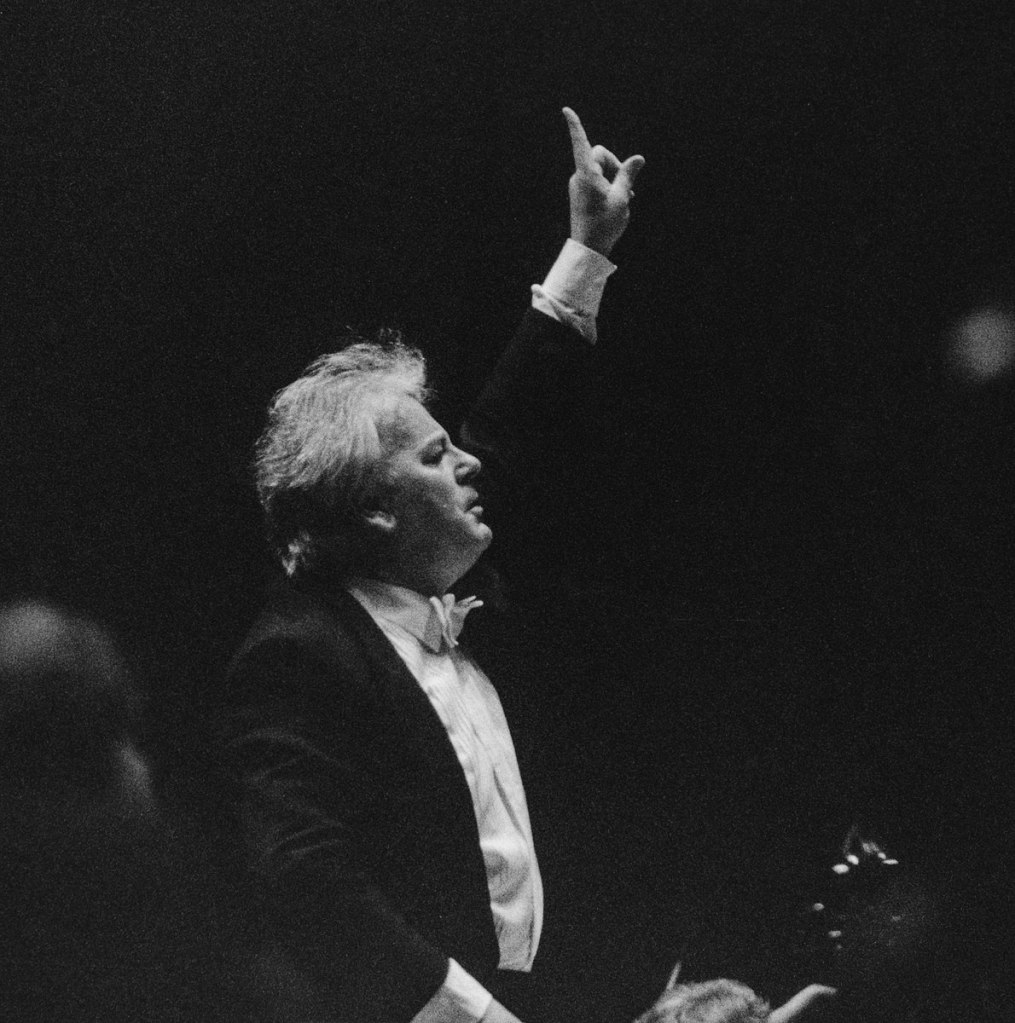

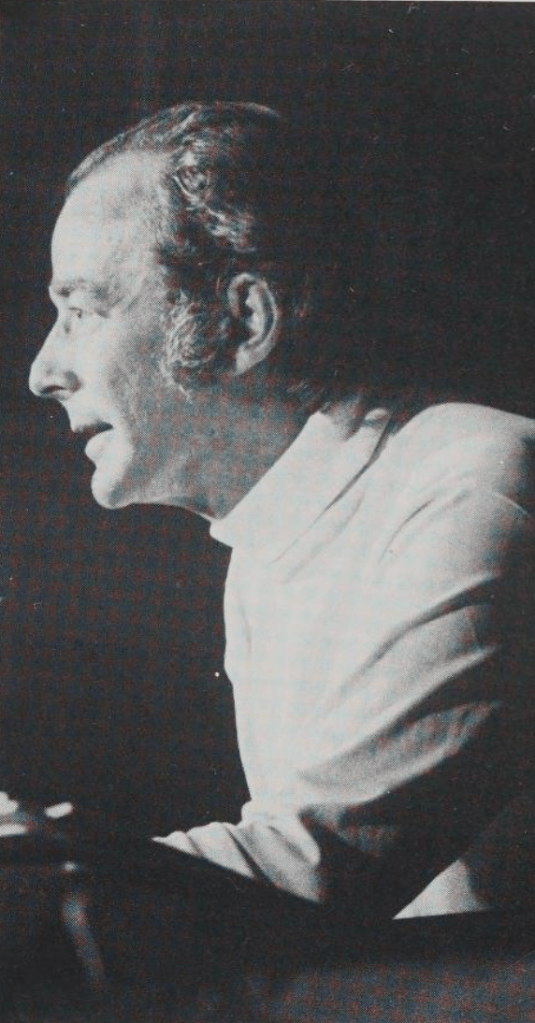

Given the length of time Barbirolli had been at the helm and the distinctive stamp he had put on the orchestra’s sound, the decision on who to replace him was a critical one. There was some conjecture that his successor would be Maurice Handford, a former principal horn with the orchestra who had been Barbirolli’s associate conductor since 1966, but in the end the Hallé Concerts Society turned to the chief conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Glasgow-born James Loughran. Loughran had first conducted the orchestra back in the 1964/5 season and after impressing in a performance of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony in the autumn of 1970, he was appointed principal conductor and music adviser in December of that year, to begin his first three-year term in September 1971.

Handford resigned his post as associate conductor on the announcement of Loughran’s appointment. Michael Kennedy’s 1982 history of the orchestra does not explicitly say that he resigned in anger, but in a typically understated phrase Kennedy says that ‘if he had felt aggrieved by the Hallé’s treatment of him, he could not have been blamed.’

As it happened, after a period conducting the Calgary Symphony Orchestra in Canada, Handford returned regularly as a guest over the subsequent two decades to conduct both the orchestra and the choir, and whilst the recordings that the choir made in the 1970s were exclusively under Loughran’s baton, those made in the early 1980s were shared between Loughran and Handford.

Apart from a brief diversion to the Pye label Barbirolli had recorded exclusively for EMI’s mighty HMV label, culminating in the mighty Dream of Gerontius recording that I described in detail in my last blog. After a four year hiatus following Barbirolli’s death, the orchestra began recording again for EMI. However, they were not to record for the main full-price HMV label but for the budget Classics for Pleasure label (CfP).

CfP had developed out of a previous EMI label called Music for Pleasure whose remit was to provide recordings of light orchestral music at a low price. CfP, however, was more highbrow in intent, providing high quality recordings of items from the standard classical repertoire at a quarter of the price of the standard classical LP, thereby occupying the same position in the market the Naxos label occupies today. It made classical recordings available to a wider, younger, audience. Indeed, as an impoverished student in Sheffield in the mid-1970s, when I wasn’t buying folk-rock LPs or punk and new wave singles my classical purchases were mainly on the CfP label.

Over the following years the choir contributed to seven recordings on the CfP label, and for all these the choral director was the redoubtable Ronald ‘Ronnie’ Frost, still remembered today with much affection by those of the choir who sang under him. I hope to devote a whole blog to him, such was his impact on the choir, so I will leave detailed discussion and description of him until that time, suffice to say he has appeared as choral director on more recordings than any other director in the choir’s recording history.

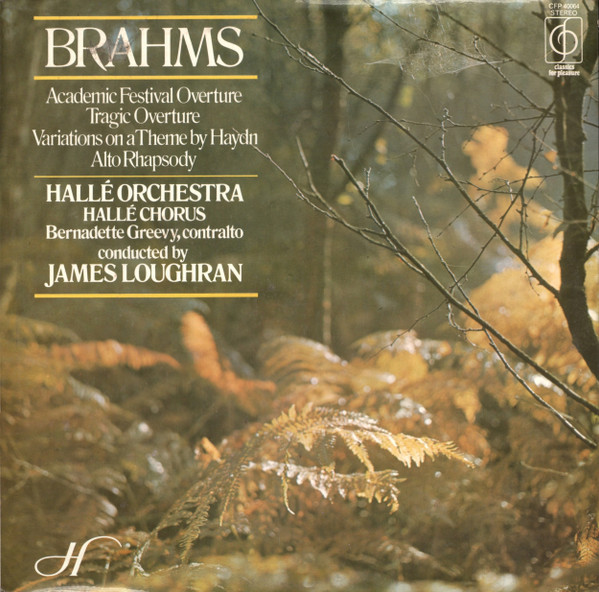

1974 – Alto Rhapsody

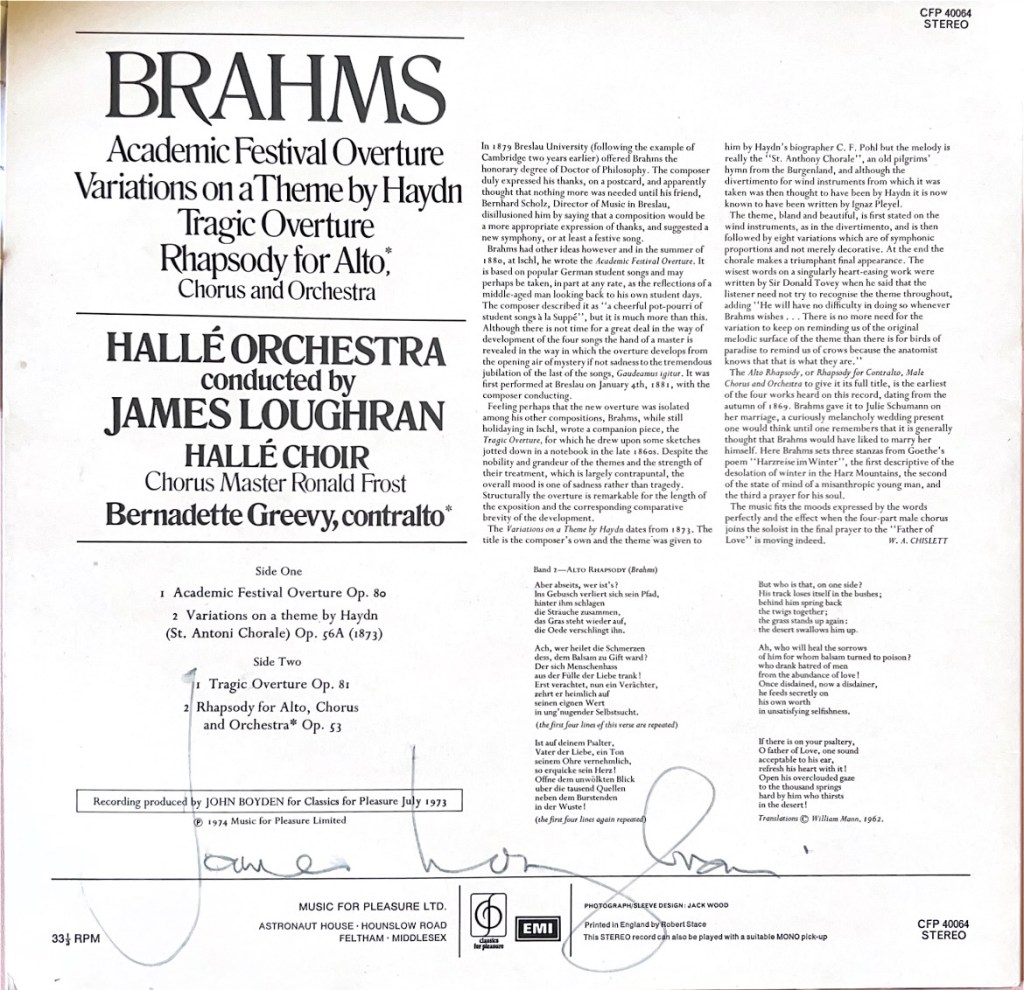

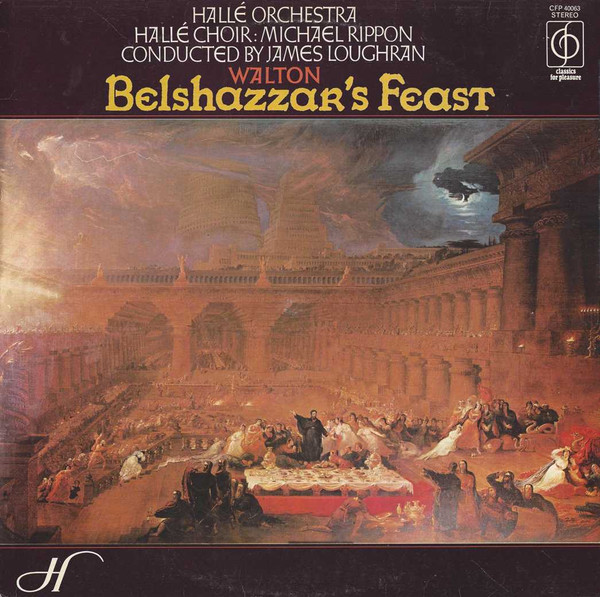

Though the first Hallé CfP LPs with James Loughran were not released until 1974, recording sessions began the year before, and these included two that involved the choir. They took place at the newly-opened Royal Northern College of Music building on Oxford Road in Manchester. The RNCM was presumably a more state-of-the-art recording option than the Free Trade Hall, and in fact all of the choir’s subsequent CfP recordings were made at the RNCM. Of the two initial recordings, the first, in July 1973 was a recording of Brahms Alto Rhapsody for orchestra, contralto soloist and male chorus that featured the young Irish mezzo-soprano Bernadette Greevy, and the second a recording two months later of William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast with Michael Rippon as the featured soloist.

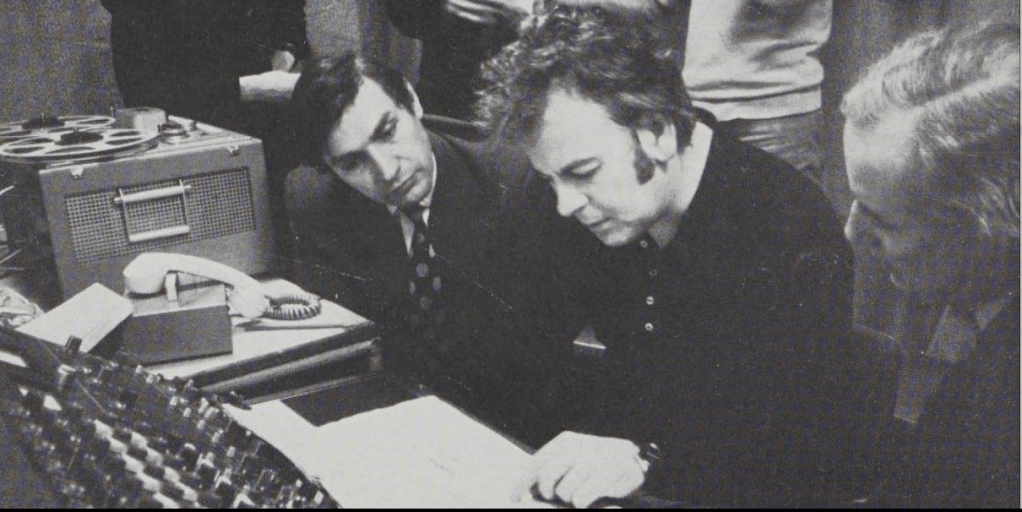

There were obviously teething problems with the new recording venue, as described by Loughran in Roger Wimbush’s Here and Now column in the September 1974 issue of the Gramophone:

For Belshazzar and the Alto Rhapsody we went into the new Northern School of Music. That proved more difficult [than the Free Trade Hall] as the choir was so far away they couldn’t hear the orchestra, but I think CFP have sorted out the problems, and they’re very pleased with the results.

Interview with James Loughran in the Gramophone – September 1974

The Brahms recording appeared in 1974 as the final item on an all-Brahms LP that was to act as a precursor to a full Brahms symphony cycle on CfP. The LP cover also contained the new Hallé Orchestra logo in the bottom left hand corner, one that would remain in use until the major rebranding early in the Mark Elder era.

It received a somewhat tepid review from Edward Greenfield in the October 1974 issue of the Gramophone, describing the ‘relatively urgent, uncontemplative view of the Alto Rhapsody‘ as ‘not the way I would want to read it, but it is warm and convincing’. The same reviewer expanded on this in the Guardian, calling the recording ‘a forthright rather than a contemplative view of a work which should sound rather more radiant’. As you will see below some of the choir’s recordings from this era are still available on streaming services such as Spotify and Apple Music, but sadly this particular item is not. However, I was able to borrow a remarkably pristine copy of the original LP from a fellow choir member. My hearing of the recording differs from both reviews. Bernadette Greevy’s singing is the every epitome of contemplative, rich in alto tone and yet supremely delicate. When the choir come in as accompaniment to her singing in the third verse of Goethe’s poem, they do so utilising their best Welsh male voice choir impression. On the whole they are held far enough back in the mix to complement Greevy’s singing but there are occasional clashes where intonation in the first basses and tenors is not all it could be, and whereas her diction throughout is impeccable, the choir’s leaves something to be desired. All in all though, speaking as someone who has never sung the piece, it comes over to my ears as an effective recording.

1974 – Belshazzar’s Feast

Two months after the Brahms session the choir reconvened at the RNCM for the second recording session for CfP. This time they were to record William Walton’s cantata Belshazzar’s Feast, a piece that had been written for the Leeds Triennial Festival and was first performed in October 1931 by the Leeds Festival Chorus and the London Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Malcolm Sargent. The following year the Hallé Choir gave the Manchester premiere of the piece under Sir Hamilton Harty and the reviewer in the Manchester Guardian was not kind. In any performance of this piece there is always the potential for rhythmic or tonal infelicities and they appear to have been realised in the choir’s performance:

Walton’s dissonances may very well sound like droppings of honey in the ears of musicians who are really contemporary, but they are calculated to outrage ordinary susceptibilities. In this performance the vocalists gave the impression more than once that the dissonances and misplaced accents were matters to get rid of as soon as possible. There was an air of relief amongst all concerned when at the end it was found that the performance really had won through more or less satisfactorily.

Manchester Guardian review of first Hallé performance of Belshazzar’s Feast – November 1932

The same problems were evident in a performance of the work in 1954, where the Guardian reviewer complained that in the lack of bite in the performance there was ‘the suggestion of ladies and gentlemen decorously singing a biblical cantata, whereas it is the primary merit of Walton’s piece that he blew the tame British oratorio tradition sky high.’

Despite these early problems, by 1974 the piece had become a staple of the choir’s repertoire, such that Gerald Larner, previewing the 1974/75 season in the Guardian, could talk of the ‘inevitable’ Belshazzar’s Feast being programmed for May 15th, 1975. Sadly no review exists in the Guardian of that concert, but given the choir had recorded the piece a couple of years previously one can imagine the work was well ingrained. Listening to the recording today much of the politeness that had marred previous live performances of the piece has gone, replaced with a concerted attack in the loud passages that, apart from a couple of tenor indiscretions, just stays the right side of uncouth. This work tends to ask the chorus to sing pp or ff with very little in between, and unfortunately the pp passages lack the bite of the louder sections with the choir frequently coming over as tentative.

Any such problems may in part have been due to the problems of distance between choir and orchestra that Loughran noted above, but though they were noticed by Edward Greenfield in his review of the LP for the Guardian, they were outweighed by other considerations: ‘The sopranos in exposed passages sound raw, but you would be lucky at a live concert to get so convincing a performance as this.’ Greenfield expands on this in his longer review for the Gramophone, describing the recording as having ‘the urgency of a live performance’, and whilst repeating his comments about the sopranos and opining that the choir were ‘by no means as polished’ as the LSO Chorus in André Previn’s then recent recording of the work, he concludes that the recording is ‘a most welcome issue none the less.’

You can judge the performance for yourself by following the Spotify link below. My ultimate conclusion is that if you judge it as a live recording it is a fine performance, but it lacks much of the nuance and subtlety you might expect from a studio recording. It is a very hard work to pull off and maybe the recording might have benefited from just a bit more studio time than was allowed.

1976 – The Planets

1976 saw the release of the first of two recordings the upper voices of the choir have made of another mainstay of the orchestra’s repertoire, Gustav Holst’s Planets suite, written by Holst during the First World War as a response both to his own burgeoning interest in astrology and to his hearing early performance of Arnold Schoenberg’s early modernist masterpiece Five Pieces for Orchestra. Though the choir only feature as a wordless chorus during the last few minutes of Neptune, the final section of the work, they are vital in bringing the work to a suitably mystical conclusion. As an example of what can go wrong, I once heard a performance by a choir (who shall be nameless!) where at their first entry the singers came in a tone sharp, thus ruining the magic that had built up during the course of the work.

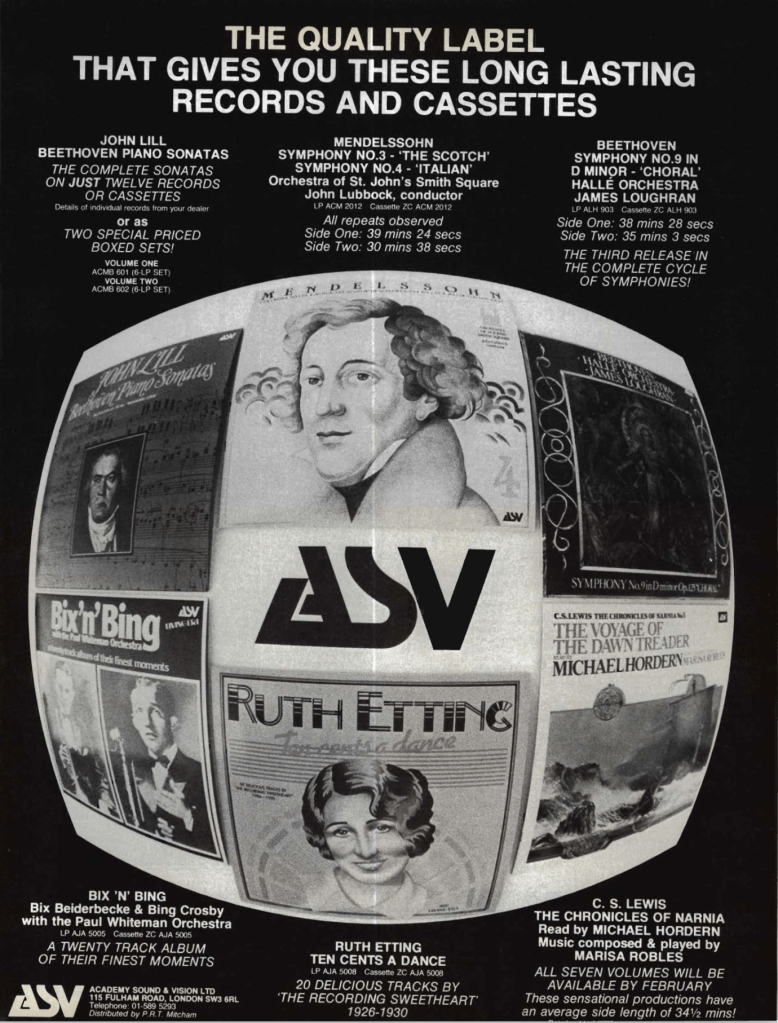

This recording of the work was actually recorded in July 1975, but not released until the following year. Again the recording venue was the RNCM and again the conductor was James Loughran. Very little of Loughran’s recorded output with the Hallé has survived into the age of streaming, unlike that of his immediate predecessor Barbirolli, and this is one that has fallen by the wayside. However it did receive the full backing of EMI’s marketing department, as can be seen by this advertisement that appeared in the Gramophone in October 1976. As can be seen, all the LPs shown were available for £1.25, which allowing for inflation would in today’s money be around £8, still very much a bargain.

Sadly I have been unable to find any contemporary reviews of the recording, though there is a Gramophone review of the CD reissue of the recording in 1990. Comparing it to Colin Davis’ recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, the reviewer feels that ‘the Loughran Planets on CfP simply doesn’t compete, I am afraid, even at bargain price’, with the ‘music-making’ sounding ‘more like a rehearsal than a real performance.’ There is no mention of the choir’s performance, though an American on-line blogger who in 2015 wrote a review of the recording in his comprehensive round-up of all the recording of the work entitled Peter’s Planets and felt that the chorus was ‘mighty fine’!

It did prove to be a very popular recording, however, no doubt helped by the bargain price, and earned a gold disc for the orchestra from EMI for sales of over 100,000.

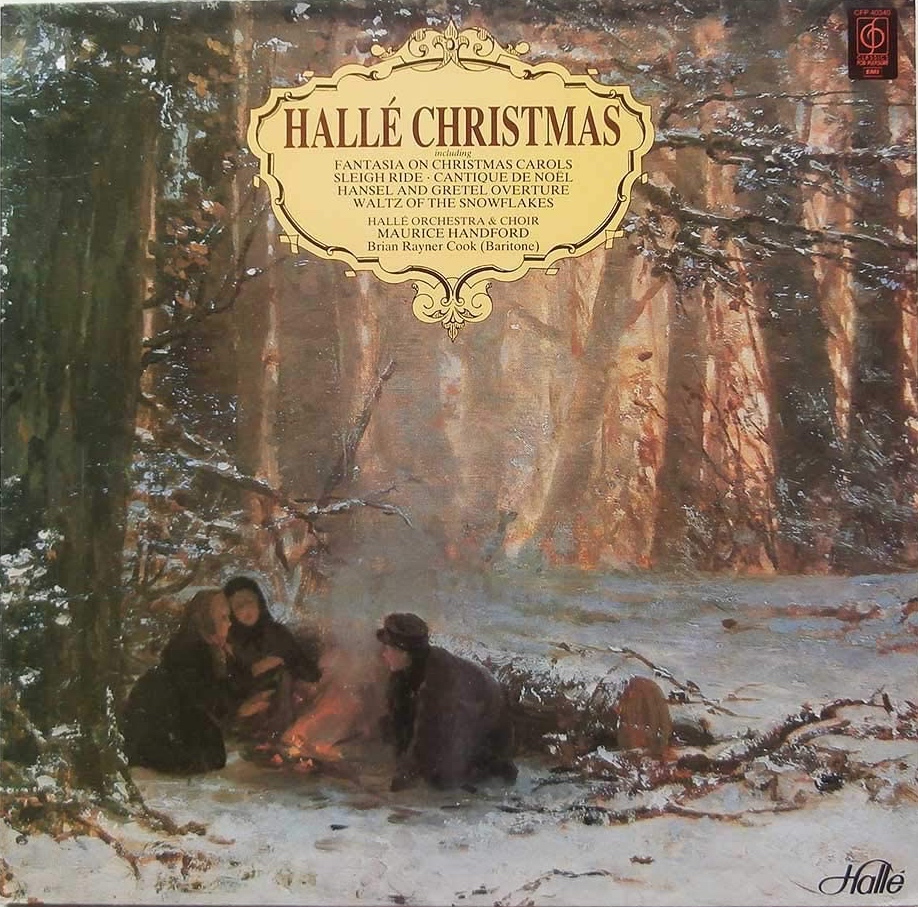

1980 – Hallé Christmas

Over the next five years, whilst James Loughran continued to record the occasional LP for CfP, his attention was mainly concentrated on a cycle of the nine Beethoven symphonies that he was recording for the ASV label, and by its very nature that cycle would only involve the choir in the final symphony. Therefore it was with much lighter fare, and not with Loughran but with the returning Maurice Handford, that the Hallé Choir returned to the recording studio for CfP in 1980. The project they were involved with was Hallé Christmas, the first of three Christmas recordings that the choir were to be involved with over the years.

As with the subsequent two recordings, this one, recorded at the RNCM in May 1980, contained a mix of various strands of Christmas music. There were orchestral favourites such as the Snowflakes’ Waltz from Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, the overture from Engelbert Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel, and Leroy Anderson’s Sleigh Ride which would later assume huge significance at the Hallé’s Christmas concert offerings. There were also a number of choral favourites, such as O Come, All Ye Faithful, Peter Cornelius’ The Three Kings, and Adolph Adam’s Cantique de Noel which in its English version O Holy Night would appear on both of the following Christmas recordings and achieve something of a cult status amongst Hallé Christmas audiences. There was also Ralph Vaughan Williams’ medley of Christmas music, the Fantasia on Christmas Carols, which featured baritone soloist Brian Rayner Cook. During the 1950s and 1960s the Fantasia had been a mainstay of the Hallé’s seasonal offerings, though sadly, because it is a fine piece, it has only been performed once by the choir in the last 15 years.

Whilst none of the above recordings have made it onto present-day streaming services, three tracks from the LP featuring the choir have been anthologised and are still available on Spotify and Apple Music., and a varied threesome they are! The first is Malcolm Sargent’s acapella arrangement of Canadian songwriter Cecil Broadhurst’s Cowboy Carol, which the choir tackle with charming gusto – a wonderful recording. They are joined by the orchestra for a rendition, in French, of The Shepherd’s Farewell from Hector Berlioz’ Christmas oratorio The Childhood of Christ. This is always a challenge for choirs in terms of intonation, but the choir tackle the tuning difficulties with aplomb in a very sensitive reading. The final extant track is the carol that is the traditional final encore in any Hallé Christmas carol concert, We Wish You A Merry Christmas, sung with a Christmas cheer that belies the May recording date. Judge the excellence of the choir’s performances by following the Spotify links below.

The recording received fulsome praise from the reviewers. Reviewing the LP in the Gramophone in November 1980, William Chislett called it ‘excellent in all respects and an outstanding bargain.’ Compact cassettes had by this time been an important extra medium for recordings for a decade, though quality issues made them possibly less suitable for classical recordings than traditional LPs. For something like a Christmas album, however, the cassette was ideal, as can be seen from the advertisement for the reissue of the album the following year. The cassette version was actually included in Ivan March’s ‘Cassette Commentary’ column in the December 1980 issue of the Gramophone, where he summed it up as follows: ‘Finally, let me recommend for Christmas the Hallé Choir and Orchestra’s “Hallé Christmas” – a well-planned concert, not just a collection of carols – conducted by Maurice Handford.’

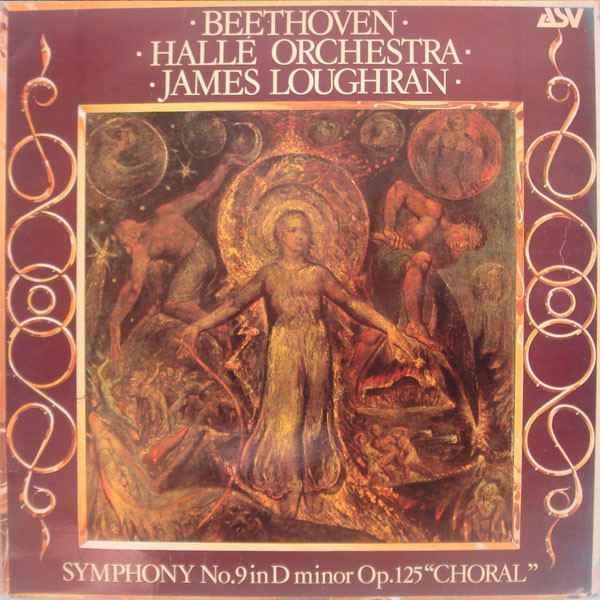

1981 – Beethoven’s Choral Symphony

It is one of the mysteries of the Hallé’s history that the recorded legacy of James Loughran’s time with the Hallé is so minimal. He conducted the orchestra for 12 years, receiving praise for his recordings of Brahms, Elgar and particular his aforementioned cycle of Beethoven symphonies. He was honoured with a CBE in 2010 and at the time of writing is still with us at the age of 92. And yet, go onto Spotify or Apple Music and look for his recordings and very few are available. On Apple Music, for example, all that remains of his many recordings with the Hallé is the recording of Belshazzar’s Feast that I covered above and an album of Viennese music also recorded for CfP. In particular, whilst there are recordings of Beethoven symphonies Loughran made with other orchestras, his Hallé Beethoven cycle is resolutely unavailable. The leading online classical CD retailer Presto Music only has 12 Loughran CDs available to buy, none of which feature the Hallé.

Michael Kennedy, writing soon after Loughran finished his term as Hallé conductor, made the following observation:

He had achieved a notable period of thorough consolidation. It cannot have been easy to follow a great man who was also something of a folk-hero, yet he rebuilt the orchestra, attracted some brilliant new principals, made recordings which won almost unanimous acclaim, gave greater prominence to the work of the Hallé Choir and maintained audiences at a high level. Many young couples in his audiences today probably never heard Barbirolli in person; to them, the Hallé was Loughran’s orchestra.

Michael Kennedy – ‘The Hallé, 1858-1983: A History of the Orchestra’, page 137

And yet, whilst Harty and Barbirolli still have countless recordings still available, Loughran has two. Therefore to get hold of a copy of the Hallé Choir’s contribution to his Beethoven cycle I had to invest in a second-hand LP. What I found, at least in the choral 4th movement, was an extraordinarily vital account of the music which makes its absence from digital release all the more regrettable.

The symphony was recorded not in the RNCM as had been the case with the CfP recordings, but back in the Free Trade Hall which the choir hadn’t recorded in since the Gerontius sessions back in 1964. The recording was for ASV, a label that specialised in classical and historical jazz recordings. For the recording the choir were joined by a fine quartet of soloists, Scottish soprano Isobel Buchanan who was only in her mid-20s at the time of the recording, frequent Hallé collaborator mezzo-soprano Alfreda Hodgson, and the stalwart operatic tenor and baritone Lancastrian John Mitchinson and Welshman Gwynne Howell. The producer for this and all the other recordings in Loughran’s Beethoven cycle, was John Boyden. Recalling the sessions, he gave this tribute to Loughran in a comment added to a tribute to Loughran on the occasion of his 89th birthday in the online blog Colin’s Column:

I made a stack of recordings with Jimmie including all the Beethoven symphonies, a set that (annoyingly) never made it to CD. I always found him to be a delight. We had to use the Free Trade Hall, with its awkward platform, which was far from matching the Bridgewater Hall. Monica is right about the backstage tensions. Following on from Barbirolli, a living God in Manchester, cannot have been easy, yet I never saw him be anything but positive and keen to do his best by the composer. They were happy days for me and I hope for him.

John Boyden writing in Colin’s Column, June 30th, 2020

Listening to the recording now, yes there are flaws – the soloists are a bit too bright and present in the mix, the choir are a bit more tied to the beat in the opening rendition of the main Ode to Joy theme and in the big fugue than might be acceptable nowadays and the German pronunciation tends more towards the English grammar school than Germany – but there is much to enjoy. The choir attack the text with fervour from the word go and maintain it through to the end, only faltering slightly at the end of the Seid unschlungen section immediately prior to the fugue that follows, and they can surely be forgiven that as that whole section is ferociously high, especially for second basses! The balance is maintained between them and the excellent orchestra, making them equal protagonists in the drama with the orchestra only gaining the upper hand in the final few pages.

Richard Osbourne, reviewing the LP in the Gramophone in December 1981, shares my admittedly unlearned opinion: ‘Loughran’s account of the Ninth Symphony is clear and consistent, admirably thought through and executed with a touch which is both deft and precise.’ He has special praise for the choir who he deems ‘sturdy and sensitive’ and concludes that it is a ‘musicianly version which succeeds in avoiding many of the musical pitfalls which put a majority of rival versions right out of court.’ Edward Greenfield in the Guardian is equally effusive, believing it a version that ‘in its fresh urgency crowns his admirable Beethoven series for ASV.’

Maybe the recording will see the light of day again sometime, but it is a real shame that at the moment it has vanished so completely. It proved to be Loughran’s last recording with the Hallé choir. He announced his intention to resign from the Hallé in April 1982 and left at the end of the orchestra’s 125th season in the summer of 1983, serving as conductor laureate for the next 8 years. Part of his reason for going may have been that the Hallé was going through one of its periodic financial crises as grants from Manchester City Council were withdrawn and the rent for the Free Trade Hall increased. The choir continued to record however, first with Maurice Handford and then with the Welsh conductor with who they would collaborate frequently during and 1980s and 1990s, Owain Arwel Hughes.

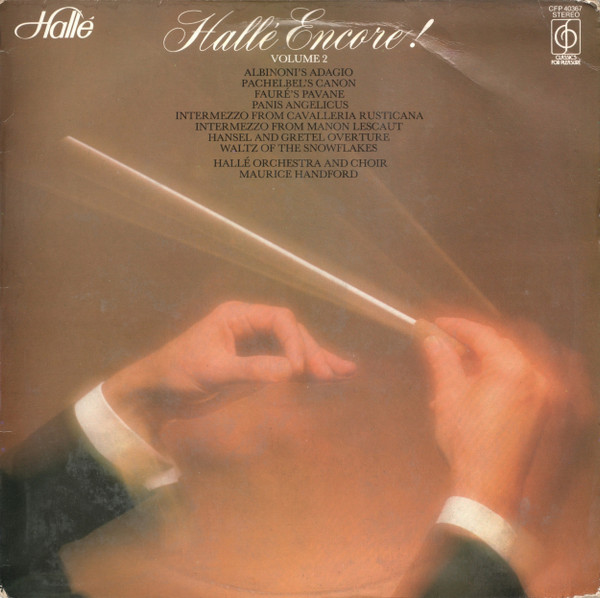

1981 – Hallé Encore Volume 2

Maurice Handford was in charge for the choir’s next two recordings. As well as recording the big works in the repertoire, CfP also specialised in recording albums that brought together choice excerpts from the orchestral and choral repertoire, excerpts that often were popular owing their appearance as film or TV themes. Amongst these were the two Hallé Encore albums that Handford recorded with the Hallé Orchestra, the first in 1979 and the second in 1981. The first volume featured the orchestra alone, including such items as the Adagio from Khachaturian’s ballet score Spartacus, famous from its appearance as the title theme for the BBC’s primetime drama The Onedin Line, and also Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings, well known at the time but destined to become even more familiar when it appeared in Oliver Stone’s Vietnam war film Platoon in 1986.

Though the recording sessions were held in the RNCM in 1979 and 1980, the album wasn’t released until September 1981. In Volume 2, whilst most of the items were purely orchestral, the choir was brought in for two items, an orchestral arrangement of César Franck’s motet Panis Angelicus, and that relative rarity, the choral version of Gabriel Fauré’s popular Pavane. Like many of Fauré’s compositions, this work went through many versions, an initial version for piano and chorus, a purely orchestral version, and finally an orchestral version with the chorus reintroduced. It is this last version that the choir perform on this album. In this version of the piece the choir do little more than add texture to the main orchestral theme, and on this particular recording the choir sit quite well back in the mix, but what emerges is a beautifully sensitive reading that makes a good case for this version to be heard more often.

In Panis Angelicus the choir is more front and centre, with the orchestra accompanying the choir rather than the other way round. Handford takes it at quite a sedate pace which creates a tendency for the choir to wallow slightly more than is desirable with the result that the sopranos permanently sound as though they’re just about to go flat, though they never actually do. Overall it is a worthy rather than an essential recording.

William Chislett reviewed the album in the February 1982 issue of the Gramophone and his attention was drawn by the Pavane recording which he ‘especially’ welcomed, feeling that ‘the vocal timbres add to the work’s effectiveness, particularly the initial entry of the female voices of the choir.’ He concludes his review thus: ‘Both choir and orchestra are in excellent form, Maurice Handford handles them effectively and the sound is very good.’

As with Handford’s Christmas album, the items on these albums have over the years been much anthologised, and the two choral items currently can be heard on Spotify and Apple Music as filler for the latest repackaging of the choir’s recording of Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, of which more below. Follow the Spotify links below to hear what the two tracks sound like.

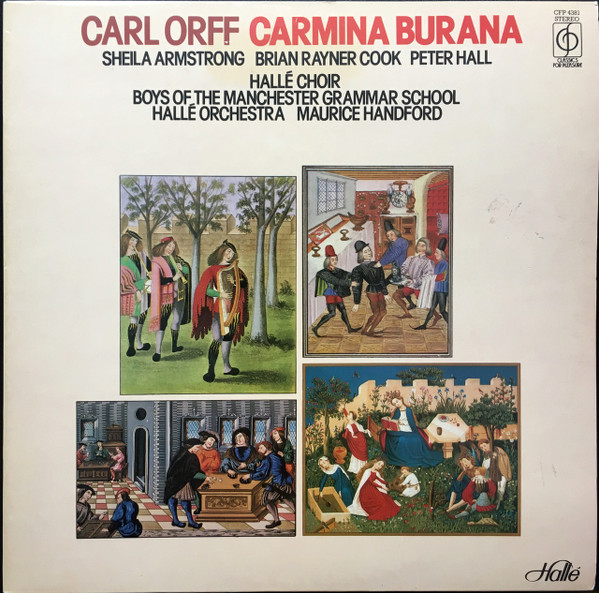

1982 – Carmina Burana

Maurice Handford’s 1982 LP of Carl Orff’s 20th century choral setting of medieval German texts, Carmina Burana, recorded at the RNCM in May 1982, proved to be his most enduring. Carmina Burana is a piece that still inspires extreme reactions, not helped by the fact that Orff was active in Germany during the Nazi era, even if he never publicly associated himself with the party, and that the work premiered in Frankfurt in 1937 at the high point of Nazi cultural ascendancy. Even if one manages to untangle the work from these associations, this is a work people either love or hate. I personally do both depending on my mood – there is much truly beautiful music in the piece and the cod-medieval rabble-rousing of some of the other music can be affecting, but the structure of the piece is simplistic in the extreme with most of the many sections featuring a simple verse-chorus structure without any proper musical development to add to the interest. One often therefore ends up with the feeling that the work as a whole is less than the sum of its parts.

It’s also a work that at face value seems simple to sing, but yet one which requires tremendous attention to detail from both choral director and conductor, and I believe there is evidence of Ronald Frost and Maurice Handford paying just such attention. This is helped in no small part by the soloists, the wonderful Sheila Armstrong in her only recording with the choir, ably supported by baritone Brian Rayner Cook and tenor Peter Hall who makes light work of his ‘swan song’. There is also a spirited contribution from the boys of Manchester Grammar School who were frequent collaborators with the Hallé when a children’s chorus was required in the days before the Hallé Children’s Choir.

The Hallé Choir’s contribution is exemplary, warm and luscious or loud and raucous according to need. The men overcome the obstacle courses contained in the In Taberna and Si puer cum puellula with ease, even if Edward Greenfield, reviewing the recording in the Gramophone complained that the men occasionally provided some ‘rough singing’ – surely isn’t that the point? In his review in the Guardian Greenfield does at least concede that ‘despite (or maybe because of) rough vocal tone from the men [the work] gains the necessary impulse and drama as it goes along.’ He believed it made a ‘good bargain choice’, or alternatively in the Gramophone that it was ‘more than enjoyable enough to make [it] an outstanding bargain at £2.25.’ As you can see, inflation was taking its toll – the choir’s first CfP recordings sold at £1.25!

The mid 1980s saw, if one takes the view that cassettes built on existing tape technology, the first major improvement in audio reproduction since the advent of the LP in the 1950s. This was the Compact Disc (or CD) format, developed by Philips and Sony in the early 1980s, in which the musical information was stored digitally on a small silver disc and read not by a needle but by a laser. Along with advancements in digital recording, the belief was that this would provide the opportunity to hear the music in a pristine form exactly as it had been created, even if some have maintained ever since that music thus recorded and reproduced lacks the warmth and presence of the now old-fashioned analogue LPs. As the 1980s progressed so many old recordings were transferred to the new digital medium. One of the first Hallé recordings to be thus transferred was indeed Handford’s recording of Carmina Burana, and the CD re-issue was reviewed by Ivan March in the November 1982 issue of the Gramophone. Sadly he found he could not find ‘anything very positive’ to say about it, though he praised Sheila Armstrong’s contribution and conceded that the performance was ‘well-rehearsed’. He preferred ‘a more joyful participation in Orff’s hedonism.’ I’m not sure I agree but that is one of the joys of listening to music, forming one’s own opinion and comparing it to those of others. You can make your own assessment by following the Spotify link below.

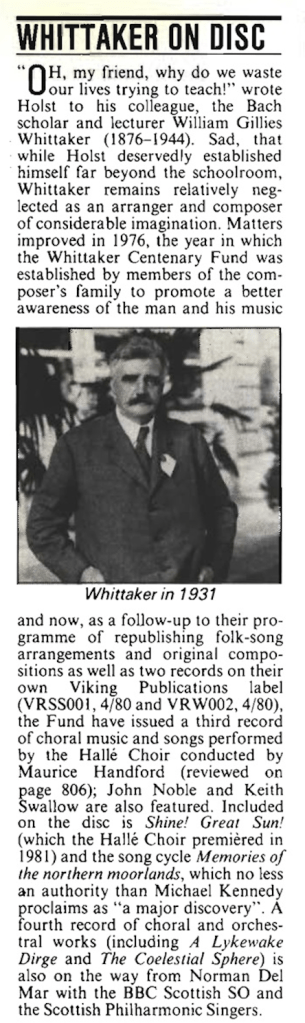

1983 – Shine Great Sun

Maurice Handford’s 1983 recording of W.G. Whittaker’s choral and vocal music, entitled Shine, Great Sun, proved to be his last with the Hallé Choir. Having served in various capacities with the Hallé Orchestra since the age of 21 he died at his home in Salisbury in 1986 after a long illness, aged only 58. In his obituary in the Guardian, Clive Smart, the Hallé’s general manager, was quoted as saying: ‘We have lost a friend as well as a very devoted member of the Hallé who did such a lot for the orchestra over almost 40 years.’

The LP was released not on one the major classical labels but on Viking Publications, which was set up by the Whittaker Centenary Fund in an effort to get more of Whittaker’s music on record. The LP was also sponsored by the City of Newcastle upon Tyne ‘in proud acknowledgement of one of the City’s most distinguished sons.’ William Gillies Whittaker was born in Newcastle in 1876, and after study at the forerunner to Newcastle University made a career as an organist, choirmaster and conductor first in his native North East and later in Glasgow. He was also an active composer, and is perhaps best known now for his folk song arrangements. Kathleen Ferrier’s signature piece was his arrangement of the folk song Blow the Wind Southerly, though given Ferrier sings it unaccompanied one wonders to what extent he ‘arranged’ it other than ensuring the notes were in the right order! More complex were his choral arrangements of folk songs, which are huge fun to sing. Of particular note is his arrangement of the North East folk song Bobby Shaftoe, which has a particular place in the choir’s history when it comes to consideration of its television appearances – I shall reveal all in a future blog.

Even more complex than these arrangements were his original compositions for choir, of which the Hallé Choir sing four on this album. Having only experienced his arrangements previously, I was astonished at what I heard when I first listened to the copy of the LP I bought for the purposes of this research (sadly there is no CD or streaming version of the album available). I was expecting something rooted in the past, but what I heard was something very much rooted in the first decades of the 20th century. Whittaker was an acquaintance of both Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams and there are definite hints of Holst in some of the music. However, there are also hints of music of a much more modernist nature, such as the later music of Frank Bridge and definitely the early music of Benjamin Britten. It is hard music, especially when unaccompanied, as three of the choir’s pieces here are (the final piece, a setting of Psalm 139, is accompanied by Ronald Frost on the organ). Sometimes the complexity seems to be for its own sake, and the lack of a narrative through-flow in some of the pieces may explain why they have not entered the mainstream choral repertoire. They are well worth any competent choir attempting, however.

In addition to the psalm setting, the choir sing three more pieces, the first being Shine! Great Sun! which the choir had premiered two years earlier. It was a setting a words from Walt Whitman’s Sea Drift, which also provided inspiration for Delius’ work of the same name. The remaining works were a setting of the Requiem Aeternam from the Requiem Mass, and Chorus of Spirits, the only choral setting of Shelley I have ever come across, and in which a soprano solo is sung by Yvonne Platt. Two further songs and a short song cycle complete the album, recorded separately in London and featuring an out-of-sorts sounding baritone John Noble. The choral elements were recorded in a venue not used by the choir before or since, the Great Hall of Manchester Town Hall, in July 1982. The quality of the recording, engineered by Tony Faulkner who had worked with the Hallé many times, is remarkable, quite one of the best pre-digital recordings of the choir I heard in researching this series of blogs. Occasionally this clarity exposes the choir in some of the more demanding passages, where there is an element of finger-crossing and hoping for the best, but on the whole the performance of the choir is excellent, and if you can get hold of a copy I would heartily recommend it.

Michael Oliver, reviewing the LP in the December 1983 issue of the Gramophone is aware of the difficulty and sometimes sheer oddness of some of the music, but praises the choir: ‘the Hallé Choir surmount the vast difficulties of this music (Whittaker the great choral trainer is exploring the limits of what concerted voices can do ) with only an occasional hint of strain.’ He concludes that ‘the recording is excellent.’ Calum MacDonald reviewed the album for Tempo magazine. Again he observes problems with Whittaker’s music in that ‘in some of the larger scores the undoubtedly fertile invention seems to lack structural focus’, but accepts that ‘there is clear evidence of an original mind, capable at its best of producing intense musical experiences not quite like any other composer.’ For the music itself he is particularly praising of the choir’s performance of Requiem Aeternam, where he feels that ‘its intense, glowing cluster harmonies, handled with great skill and harmonic logic, are almost a weird foreshadowing of Ligeti.’ Not quite what one might have expected from a man who had arranged Bobby Shaftoe!

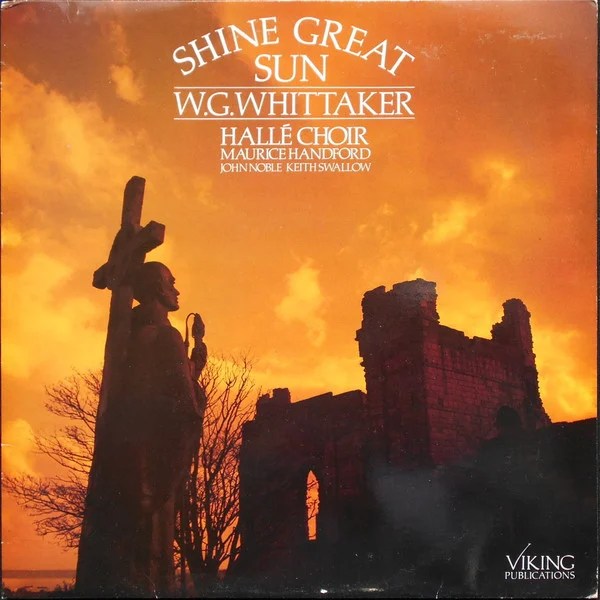

1984 – Much Loved Music

Here’s Owain Arwel Hughes writing in his 2012 autobiography about the experience of working with the Hallé Choir from the 1970s onwards and particularly his debt to Ronald Frost:

[I]t’s no coincidence that my development and progress as a choral conductor was cemented with my activities with the Hallé. Its choir was a revelation, scrupulously auditioned, and thoroughly professional in its attitude, as befits an organisation such as the Hallé. The chorus master, Ronald Frost, a church organist and choir master, was equally professional, and ruthlessly thorough in his preparations. He was engaged as a chorus master, and that, simply, was what was expected of him, no histrionics or climbing above one’s station, but to train the choir to perfection.

From ‘My Life in Music’ by Owain Arwel Hughes

Owain Arwel Hughes, born in 1942 in the Rhondda and like James Loughran very much still with us, still very much active as a conductor and the cousin of one of the choir’s basses, did as much as anyone to raise the profile of the Hallé Choir on the national stage. In the mid 1970s he had conducted the choir in both a televised performance of Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast from the Free Trade Hall and an associated ‘in rehearsal’ programme that showed Huges rehearsing the choir in excerpts from works such as Messiah and Elijah. This led in 1981 to an choir appearing in an episode of Hughes’ BBC television series The Much Loved Music Show, a series in which he moved round the country conducting different orchestras and their associated choirs in popular items from the choral and orchestral repertoire. I’ll say more about the actual television series in a later blog, suffice to say that according to Hughes ‘a happy consequence of this exposure was to increase the numbers attending live concerts, a timely boost for orchestras struggling to maintain audiences.’ Would that the BBC held as closely to its public service brief today.

One upshot of the series was an invitation in 1984 for Hughes to conduct the Hallé and Hallé Choir in a recording for CfP called Much Loved Music, the title harking back to the TV series. Recording sessions took place in July 1984, once again in the RNCM. The repertoire chosen for the choir to sing consisted of three opera choruses, the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves from Verdi’s Nabucco, the Easter Hymn from Mascagni’s Cavelleria Rusticana with soprano Pamela Coburn, and the Anvil Chorus from Verdi’s Il Trovatore, and three items from the standard choral repertoire, Bach’s Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, “Let The Bright Seraphims” from Handel’s Samson, again with Coburn, and the “Cum Sancto Spiritu” from Rossini’s Petite Messe Solenelle. Sadly none of these recordings have made it onto streaming services, but I managed to find a second-hand copy of the CD. Apart from a slight tendency occasionally for the men to oversing, the choir sound splendid throughout, as do the orchestra. William Chislett, writing in the Gramophone in January 1985, most certainly agreed: ‘”Owain Arwel Hughes conducts Much Loved Music” lives up to its title admirably.’ He has further good words to say about the choir: ‘Many years ago I was very familiar with the Hallé Chorus in the flesh and it is good to find them in fine form.’ He concludes as follows: ‘good digital sound makes its contribution to a record that is a bargain at £2.25.’

This final comment of Chislett’s is worth commenting. Though many of the choirs earlier recordings were re-released on CD, this is the first of the choir’s recordings that was first released on CD. Moreover it was recorded digitally rather than onto analogue recording tape. All subsequent choir recordings (except one that I will mention in the final part of this blog) has been issued first on compact disc.

1993 – Battle of the Atlantic Suite

The choir made no recordings at all between 1984 and 1993. This period largely coincided with the Polish conductor Stanisław Skrowaczewski’s stint as principal conductor of the Hallé. He had been appointed to the role to succeed James Loughran in 1983 having led the Minnesota Orchestra for many years following his defection from Communist Poland in 1960. He was to serve until 1992, but it was obvious that the choir was not one of his main priorities. Unlike all of the other principal conductors since Hamilton Harty he made no recordings with the choir and indeed only conducted two radio broadcasts with the choir, in 1986 and 1989.

It was therefore not until the arrival of Kent Nagano in 1992 that the choir’s recording fortunes revived, though not with a performance conducted by Nagano himself. The first CD that the choir had produced in nine years was the 1993 recording of the Battle of Atlantic Suite, written by Dave Roylance and Bob Galvin to commemorate the general cessation of hostilities in the Battle of the Atlantic during World War 2 50 years previously. The CD was a follow-up to the same pair’s recording of the Tall Ships Suite and was conducted by Bill Connor, with Lesley Garrett as the soprano soloist. I have written about this recording at length in my previous blog looking at the choir’s premieres and will not repeat those words here, other than to note that I could find no reviews of the recording, though a live recording of parts of the suite re-arranged for military band with Lesley Garrett again singing (but with no choir) was reviewed in the Gramophone the following year. Of all the recordings that the choir has made, this is therefore perhaps the one that is now the least well known. Listening to the music now, that is perhaps no bad thing.

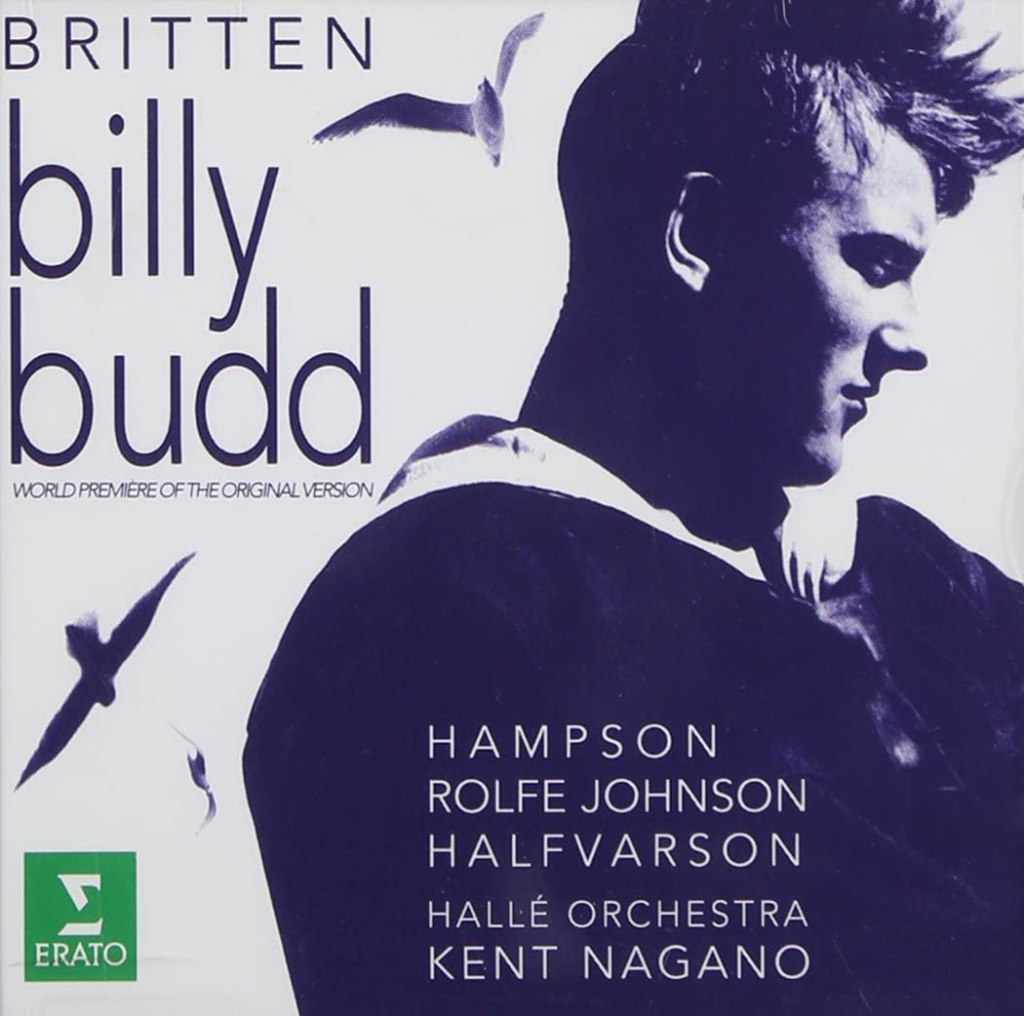

1998 – Billy Budd

The American conductor Kent Nagano came to the Hallé in 1992 with ambitious plans for the orchestra and indeed he succeeded in both raising its profile and its musical standards. However, this came at a cost, as much of his programming proved much too costly for an orchestra already in a perilous financial position. An article by Ian Herbert in the Independent in 1999, describing the Hallé Concerts Society’s decision not to renew Nagano’s contract, talks of ‘tensions surrounding the musical director’ which ‘were evident as musicians took a pay freeze last year [1998] and jobs were lost.’ The title of the article summed up the situation: ‘Manchester’s debt-ridden Hallé Orchestra loses star performer.’

During Nagano’s tenure the choir featured in two ambitious recording projects, both in 1998, the year of maximum financial peril. They were on Warner Brothers’ France-based classical Erato label, Nagano’s label of choice. Both took works from the standard repertoire and presented them in distinctly different ways. The first was a recording of Benjamin Britten’s opera Billy Budd, which was based on a novella by Herman Melville about murder and mutiny on board a Royal Navy ship at the beginning of the Napoleonic Wars. The libretto for the opera was adapted from the novella by E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier, and the work was first performed at the Royal Opera House in December 1951. The nature of the story is such that the opera employs an all-male cast, so choral duties for this recording were restricted to the the tenors and basses of the choir, trained now by Keith Orrell. They were joined by the trebles of the Manchester Boys Choir, a choir founded in 1981 that achieved high standards during its short life. The gap left when the choir folded in 2001 was essentially filled by the formation of the Hallé Children’s Choir.

The unique selling point of this recording was that it was the first ever recording of the original four-act version of the opera. It was in this form that the opera was first performed in 1951 but Britten had second thoughts about the dramatic structure of the work and created a two-act version for a BBC broadcast in 1960 and it is this version that is usually performed and recorded today. Nagano employed an all-star (and presumably quite expensive) cast with American baritone Thomas Hampson as Billy Budd, Anthony Rolfe Johnson as Captain Vere and Eric Halfvarson as Claggart. The recording was also unique in that it was the first time the choir had recorded in the Bridgewater Hall, the newly-built concert hall that had replaced the old Free Trade Hall in 1996. Though the CD recording was to be released in 1998, the recording was actually made in May 1997. Following a practice that became increasingly common in subsequent decades, the recording was largely put together from concert performances of the opera in front of an audience. The choir’s contribution as the crew of the ship is mainly restricted to the occasional piece of commentary on the action, but they come into their own in three places, first in the rousing climax to Act 1, then in the interlude in Act 2 where they emerge from the texture singing a mournful pseudo-shanty and finally towards the end of the opera in Act 4 where they provide a harsh wordless chorus as Billy Budd awaits his execution. To my ears, whilst their singing is strong and committed, the choir could have been put a little bit higher in the mix, but that is a minor gripe.

A minor gripe indeed as the recording received a 5-star review from Edward Greenfield in the Guardian, who especially praised the ‘thrilling fortissimo close to the original Act 1, superbly achieved in Kent Nagano’s powerful performance with the Hallé Orchestra and Choir.’ Alan Blyth, reviewing the recording in the March 1998 issue of Gramophone, commented on the fact that the recording had been made in the new Bridgewater Hall and the ‘amazingly wide spectrum of sound on the recording’ that resulted, though he qualified this with a comment that as a result ‘sometimes the orchestra is simply too loud’, though overall he feels it is a ‘wonderfully full-bodied, accurate and detailed account of the many-faceted score.’ The choir get a special mention, with Blyth recommending ‘this new version which, in almost every respect, is equal to the demands of a technically difficult piece, not least as regards the choirs taking part.’ The reissue of the recording under the Warner Opera Collection imprint in 2011 brought an on-line review, courtesy of John Sheppard writing on the MusicWeb International website. Sheppard echoes my one misgiving about the choir’s performance: ‘the chorus sing accurately and lustily but without the dramatic projection that one expects from an operatic chorus.’

The recording is still available on Spotify and Apple Music. Follow the link below to hear the Spotify version.

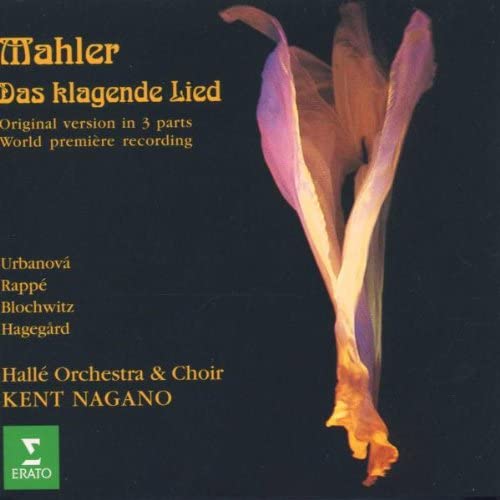

1998 – Das Klagende Lied

The second of the Hallé Choir’s two recordings with Kent Nagano was, like the recording of Billy Budd, largely derived from a live recording given in the Bridgewater Hall in October 1997, with the CD being released the following year. In such recordings, the concert recordings are usually patched with sections taken either from rehearsals before the concert or patching session carried out after the concert, usually to cover some stray audience noise or a fluffed note or two. In this recording, however, a major piece of audio subterfuge was carried out post-concert, of which more below.

Das klagende Lied, or ‘Song of Lamentation’, is one of Gustav Mahler’s earliest works, begun when the composer was only 18. In its original version this was a monumental piece in three parts lasting over an hour with multiple vocal soloists including two boy soloists, a large choir and a typically large Mahlerian orchestra. The work did not receive its first performance until 1901 but by then Mahler had made many alterations to the original score, reducing the number of soloists, removing the boys’ solo parts and rescoring the work into two rather than three parts. However, the parts for the original version did survive, and Nagano decided to present this version at the Bridgewater Hall, with the subsequent CD being advertised as a ‘world premiere recording’. Nagano assembled the full Hallé Choir and four impressive soloists supplemented, to make up the original numbers, by soloists from within the choir and a treble and an also soloist from the Manchester Boys Choir.

Andrew Clements reviewed the concert for the Guardian and gave Nagano full marks for bringing this version back into the repertoire – ‘the full, unadulterated Klagende Lied is a fascinating document as well as a compelling experience in its own right.’ However, he was less sure about the concert performance itself:

This first performance, though, did not quite measure up to the excitement of the occasion. The Bridgewater Hall, a year-old now, still has problems coping with a full orchestra playing at anything above forte, and the rather spotty playing and tentative singing, from the Hallé Chorus, … suggested that a couple more rehearsals would have been time well spent.

Review of Das klagende Lied in the Guardian – October 8th, 1997

Normally when recording a work as well as performing it such problems can be taken care of in the patching process. However, for this recording a radical, and perhaps slightly unethical, fix was found for one aspect of the performance that was obviously deemed unsatisfactory, namely the boy soloists. Rather than re-record them or use rehearsal takes, the decision was made to completely replace them in the recording. Thus the eventual CD release features not the original boy singers but two soloists from the Wiener Sängerknaben (Vienna Boys Choir), recorded separately sometime later in Vienna.

However it was derived, the final recording reveals a work that shows the young Mahler already in full control of the passionate late romantic style that would become so familiar in his later symphonies and song cycles. The choir sound confident throughout, strident or mysterious as required with any ‘spottiness’ seemingly removed, though once again they seem a bit too far back in the mix. The overall quality of the recording makes it odd that it has slipped out of the catalogue and is no longer available even on streaming services – I was only able to hear it thanks to a choir member lending me their original copy.

Having reviewed the original concert for the Guardian, Andrew Clements also reviewed the CD when it was released, and gave it a much more favourable verdict than he had given the concert. Whilst the original concert ‘failed to catch fire… on disc it’s another matter… Mahler completists will certainly want to hear his first thoughts on a cantata that contains so many of the fingerprints of the later masterpieces.’ Alan Blyth, writing in the Gramophone, was less sure, comparing it unfavourably to the Riccardo Chailly recording of the revised score. Whilst ‘Nagano’s Hallé players cover themselves with glory under his almost demonic direction’, in comparison to Chailly’s ‘superb pacing and precise attack’ Nagano ‘goes for a more subjective and in the end exhausting approach.’

1999 – Mahler’s Third Symphony

That would be it for my round-up of recordings of the Hallé Choir that were released between the departure of John Barbirolli and the arrival of Mark Elder, had I not come across mention of a 1999 CD release of a recording the choir had made back in July 1969, back in Barbirolli’s time in charge of the orchestra. It was a recording of Mahler’s epic Third Symphony made under studio conditions by the BBC in Manchester, with the women of the Hallé Choir, the boys of Manchester Grammer School and Kerstin Meyer as the mezzo-soprano soloist. Mahler scholar Deryck Cooke thought the recording worthy of a commercial release by EMI, but apparently the label were more interested in a live recording of the symphony by Barbirolli with the Berlin Philharmonic made a few weeks earlier, and so no LP ever materialised. Sadly, the CD itself is now no longer in the catalogue and as it is also not available on streaming services and second-hand copies of the CD are very expensive it’s one of the recordings I’ve not been able to listen to.

However, it was reviewed by David S Gutman in the January 1999 issue of the Gramophone, and his review, while slightly ambivalent, is generally favourable – ‘admirers of the conductor will not hesitate.’ Of the choral 5th movement, “Es sungen drei Engel”, Gutman simply says that the orchestral commitment present earlier in the symphony ‘extends to a boisterous ‘angels’ movement. Tony Duggan, writing in 1999 on the MusicWeb International website what was surely one of the choir’s first on-line reviews, was more effusive, giving the recording 4 stars and comparing it more than favourably with Simon Rattle’s then recent EMI recording of the symphony with the CBSO. Duggan especially liked the contrast between the boys and women in the fifth movement:

The boys of Manchester Grammar School are nowhere near the pretty angels we are used to elsewhere. These are urchins from the mean streets of Manchester and they give an earthier quality to match the purer sounds of the women and the darker tone of Kerstin Meyer.

Excerpt from Tony Duggan’s review of Barbirolli’s Mahler 3 recording on MusicWeb International

As you have seen above, whilst the period between Barbirolli and Elder may not have been one of the most settled in the Hallé’s history, for the choir it provided multiple opportunities to record a wide variety of wonderful music, usually to much acclaim. The arrival of Mark Elder would herald a new era, and a particular concentration a very special part of the Hallé’s musical heritage, the music of Edward Elgar. As you will see in part three of this blog they have been very special years for the choir.

[Blog edited on September 13th, 2023 after listening to the LP recording of the Brahms Alto Rhapsody]

References

Guardian and Manchester Guardian archive, courtesy of Manchester Libraries

Tempo magazine archive, courtesy of jstor.org

The Gramophone magazine archive, courtesy of gramophone.co.uk

MusicWeb International, http://www.musicweb-international.com

Peter’s Planets https://petersplanets.wordpress.com/2015/01/01/loughran-1975/

Colin Anderson, ‘Many Happy Returns to conductor James Loughran, Barbirolli’s successor at the Hallé, 89 today.’, Colin’s Column, June 30th 2020 https://www.colinscolumn.com/many-happy-returns-to-conductor-james-loughran-89-today/

Duncan Hadfield, ”Classical & Opera: The Halle Orchestra, conducted by Kent Nagano”, The Independent, May 23rd 1997

Ian Herbert, ”Manchester’s debt-ridden Halle Orchestra loses star performer”, The Independent, May 24th 1999

Owain Arwel Hughes, My Life in Music (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2012).

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé: 1858-1983 : A History of the Orchestra (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982).

Peter Scott, ‘James Loughran, Hallé Orchestra, 1975’, Peter’s Planets, January 1st 2015 https://petersplanets.wordpress.com/2015/01/01/loughran-1975/

Leave a reply to Make A Joyful Noise – The Hallé Choir on TV – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply