Introduction

The vast majority of performances by the Hallé Choir through the years have been by their very nature ephemeral. The choir have turned up at the Free Trade Hall, or Bridgewater Hall, or an out of town venue and done their stuff, and the memory of the performance has existed simply in the minds of the choir and its audience, or in the words of a newspaper review. Very occasionally, however, a concert has been memorialised in the form of a record, be it cylinder, shellac or vinyl, or more recently a compact disc or digital file on a streaming platform, thus enabling future generations of classical music lovers to trace the development of the choir through sound. Over the years the choir has been involved in well over 30 recording sessions that have resulted in commercially available product, from the first in 1928 through the latest, recorded just before the pandemic in 2019, with a similar number of different composers being represented within those recordings.

This is the first part of will end up as a three-part blog outlining the history of the Hallé Choir on record, outlining the recording history of the choir from that first 1928 recording through to possibly the most iconic recording session the choir has ever been involved with, John Barbirolli’s 1964 recording of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius released in 1965. The second part of the blog will look at the many and varied recordings that were made between the departure of Barbirolli in 1968 and the arrival of Mark Elder in 1999, and the final part will cover the ‘Elder years’.

The Development of Choral Recording

The first Hallé Choir recording came 40 years after what is almost certainly the first ever recording made of a choir. On June 29th 1888 during the Crystal Palace Handel Festival 4,000 singers gathered in that vast edifice for a performance of Handel’s oratorio Israel in Egypt, a performance very much in the tradition of large-scale performances of Handel I wrote about in my first blog in this series. Attending that concert was the American Civil War veteran George Gouraud who was in the process of introducing the Edison Phonographic Cylinder recording technique to England, whereby sound entered through the horn of the recording device and was transcribed directly onto a wax cylinder. Gouraud brought just such a device and recorded part of the performance. The recording was made at a distance of about 100 yards from the choir and over time the recording has degraded, but in the YouTube clip above you can just about make out the semblance of a performance.

This early type of recording became known as ‘acoustic’ recording to differentiate it from the ‘electric’ recording technique that began to be used in the early 1920s, of which more later. It was the method used, for example, by some of the early folk song collectors in the early 20th century to record the songs rather than simply transcribe them. One of these was Percy Grainger, and I will talk more about that in Part 3 of the blog, when talking about how early recording, Percy Grainger, and the choir came together in a 2003 CD release.

The inherent problem with the acoustic process was that in order for sound to be recorded, if you didn’t have the luxury of 4,000 voices singing at you, the musicians had to gather close to the horn, which restricted the number of musicians that could be recorded at any one time. Also for singers, not to put too fine point on it, they had to be loud! This inevitably meant that classical recordings of chamber pieces or orchestral pieces with reduced orchestrations were more likely to be effective. Large scale studio recordings of choral pieces were impractical; as an Edison-Bell engineer was quoted as saying, ‘Good recordings of choruses are not easily made, as the greater the number of singers, the more complicated do the sound waves become.’ Editing was also not possible given that the recording was being made directly onto the wax cylinder, or later a shellac disc – if mistakes were made the cylinder or disc would be discarded, a new one would be attached, and the performers would start again.

Hamilton Harty

Among the early classical recording artists was the young Irish pianist, composer and conductor Hamilton Harty. Beginning with a recording of the Irish tenor John McCormack in 1910, for whom he arranged a setting of the traditional song My Lagan Love, he was involved in a number of recordings of pieces of chamber and light classical music, first as pianist with the cellist W.H. Squire, and later as conductor of a small orchestra, often with notable singers of the day such as Clara Butt or Norman Allin. Most of these were on the Columbia label (the term label comes from the process whereby the record companies decided the best way to identify recordings was to stick a piece of paper, or ‘label’, in the middle of the final disc). The Columbia Graphophone Company were originally the UK subsidiary of the Columbia Phonograph Company in the USA, but when that company collapsed, they continued on their own, eventually merging with the Gramophone Company to form Electrical and Musical Industries, known to all and sundry as EMI. EMI became a giant of the recording industry, particularly via the label HMV (short for His Master’s Voice). It was a company for whom the Hallé and the Hallé Choir would record many times over the years.

Hamilton Harty’s star was rising fast in the classical music world, particularly as a conductor but also as a composer (the Hallé Choir would perform his cantata The Mystic Trumpeter, based on Walt Whitman poem, on more than one occasion). He made his debut conducting the Hallé Orchestra in 1914, and after one of the orchestra’s periodic crises following the departure of Thomas Beecham as musical adviser, in 1920 he was appointed chief conductor to help steady the ship and improve the quality of the orchestra. There also appears to be an element of improving the quality of the choir, at that time still rebuilding after the Great War, sharing responsibility for that improvement with the choral director. A profile of Harty from 1941 makes this point: ‘Harty arrived with ideas, one of which was the transference of a greater part of the training of the rather unwieldy Hallé Choir from the chorus-master to himself. He called it a “thorny problem which to my mind has hardly been satisfactorily handled in the past.”‘

In these aims he largely succeeded. Michael Kennedy describes him as ‘a complex personality, one who could coax and charm an orchestra to give superb performances, or, if the mood took him, could plough unsympathetically through a work.’

Throughout his period with the orchestra Harty involved them in his recording relationship with the Columbia label, beginning with a recording of Handel’s Water Music in 1920. These early recordings would still have been acoustic, but a revolution in recording technology soon came courtesy of the American company Western Electric – the process of ‘electrical’ recording. Simply put, in this process the sound was picked up not by an acoustic horn but by a single electric microphone connected to an amplifier which was then linked to an electromagnetic recording head. This still recorded directly onto a disc, meaning editing was still not possible, but the use of a microphone and amplifier meant that more musicians could be involved in the recording and that the recording process could pick up sounds at a much lower volume than previously. For example, in popular music it led directly to the emergence of the ‘crooners’, singers who, without having to shout, could sing with a degree of subtlety. As Bob Stanley says in his excellent recent history of early pop music, ‘having a naturally loud voice suddenly became unimportant, the width of your chest entirely irrelevant.’ In terms of choral singing, it meant that large numbers of singers could be picked up by the microphone and rendered faithfully. From around 1925 onwards, as electric recordings began to outnumber the old acoustic records, large scale choral works therefore began to be recorded properly for posterity.

The Hallé were described in publicity as ‘exclusive’ Columbia recording artists, and through their records being released also on the American Columbia label, the orchestra’s fame spread across the Atlantic. An early issue of The Phonograph Monthly Review in 1927 devoted a whole feature to the Hallé and their recordings under Harty and were fulsome in their praise: ‘Sir Hamilton and his orchestra are now at the heights of their powers and music lovers may well anticipate their future works. We all have had much to thank them for in the past… and we hope to have more of their splendid recordings before long’.

1927 – By The Wayside

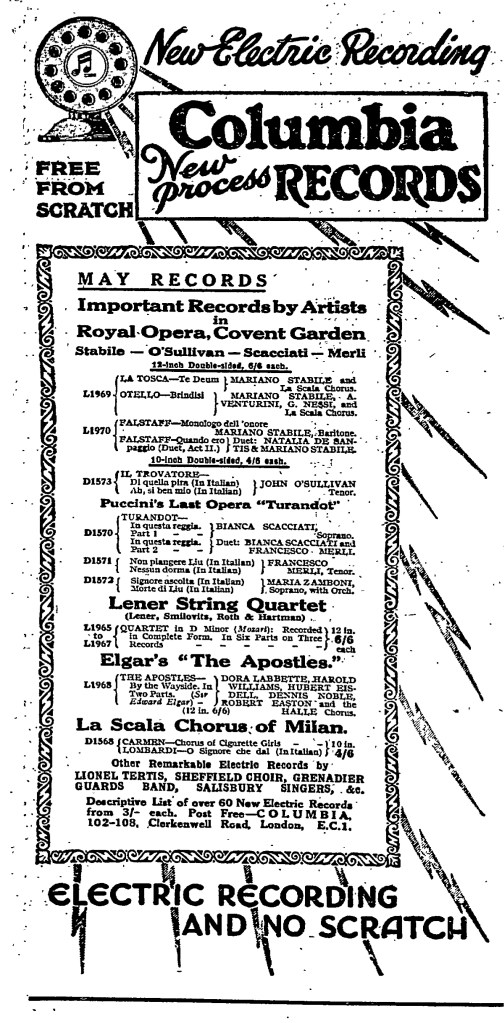

One such recording was being released in the UK in the very month that article was being published and, as far as I have been able to ascertain, it was the first recording ever to feature the Hallé Choir (or the Hallé Chorus as it was more commonly known then). Advertised in the Guardian as being one of a series of ‘new electric recordings’ using Columbia’s ‘new process’ it was a recording, conducted by Harty, of a section of Elgar’s The Apostles, specifically the section recounting the story of the Sermon on the Mount, which Elgar entitled ‘By the Wayside’. The choir had performed the oratorio under Harty in March of the previous year, having been trained by their still relatively new choral director Harold Dawber, who had succeeded the long serving R.H. Wilson in 1925. The performance was a success, the Guardian proclaiming that ‘Elgar is alive in every note’.

The choir, orchestra and conductor reconvened in January 1927 to record By the Wayside for Columbia, though only Dennis Noble of the 1926 soloist remained, joined for the recording by Dora Labbette, Harold Williams, Hubert Eisdell and Robert Easton. Other recordings made by the Hallé around that time were made in the Manchester Free Trade Hall, so my assumption is that this one was too.

The new electrical technology should have allowed a large contingent of the chorus to be present at the recording. Indeed, other choral recordings reviewed in the Gramophone at the same time as this one make great play of the number of singers involved – a recording made in Leicester is described as involving 3,000 voices and one recorded in the ‘Columbia London factory’ 1,500 voices. However, as you can hear by following the Spotify link below the recording very much has the feel of the chamber performance, with the soloists front and centre and what sounds like a very much reduced orchestra and choir as a background accompaniment. It very much suits the intimate nature of this section of the oratorio. The result is a very affecting performance, seemingly combining the subtlety of an electric recording with the reduced numbers that had been normal in an acoustic recording. It is also a fascinating first opportunity to hear the choir, albeit in chamber form, nearly 70 years on from their first performance. The choral interjections are pleasingly consistent with good intonation, and if the choir occasionally has a tendency to swoop onto the note that merely reflects the normal practice of the day given the soloists are often doing it too!

What of the contemporary reviews of the recording? ‘Discus’, writing in The Musical Times thought ‘the blend of soloists, chorus and orchestra is unusually good, though the orchestra is a little too much in the background’, and felt ‘the success of this extract from a noble and still too little known work is full of rich promise’.

The review of the recording in the Gramophone magazine is slightly more grudging in its praise, noting some dissatisfaction with a couple of the soloists and complaining that ‘Columbia still give too much bad tone to be ignored’, though overall they thought ‘if this last fault could be corrected one would be very grateful to have more records like this.’ New digital technology has allowed just such corrections to be carried out – the Spotify link below is to a digitally corrected and remastered version of the recording that was released in 2011.

One final thing that should of course be mentioned is that a 78rpm record at that time could only hold a maximum of about five minutes of music, so when released the recording was split over both sides of the record. It could only be heard complete when joined up for the modern re-release. Recordings of longer pieces would spread over a number of discs which were presented for sale in a package that resembled a photo album. The recordings therefore became known as ‘albums’, a term which continued to be used for recordings even when technology allowed them to be held on a single long playing record or compact disc.

1929/30 – Rio Grande and Nymphs and Shepherds

That, surprisingly, was the last recording that Hamilton Harty made with the Hallé Choir. However, there are two further commercial choral recordings that Harty made during his tenure with the choir that have a connection with the choir, one directly and one indirectly.

I talked about the direct connection in the second part of my blog about Hallé Choir premieres, ‘Beyond the Rio Grande‘. To briefly summarise that story, Constant Lambert’s jazz-influenced cantata The Rio Grande was given its first concert performance by the Hallé Choir and Orchestra under the composer in December 1929. However, when the piece came to be recorded for the first time the following month in London it was Harold Darke’s St. Michael’s Singers who sang, not the Hallé Choir. Whether it was the slightly less than flattering reviews that the choir got at that first performance or the expense of ferrying the choir down to London for the recording, the exact reasons for this switch are lost in the mists of time, Suffice to say that we can file it as ‘one that got away’.

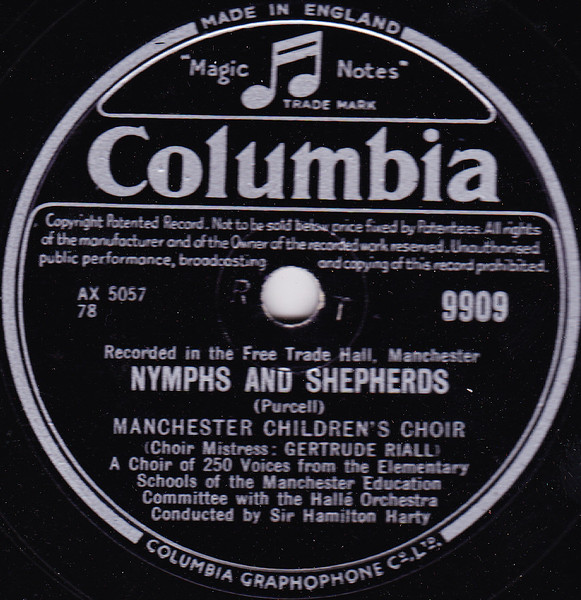

The recording with the indirect connection is a happier tale. The story of the Manchester Children’s Choir and their recording of Henry Purcell’s Nymphs and Shepherds and Humperdinck’s Dance Duet from Hansel and Gretel has achieved legendary proportions. The choir had been formed in 1925 and was led with gusto by the indefatigable Gertrude Riall. It was composed of up to 250 singers chosen from primary schools within the Manchester area, with one of the objectives being to give those with no formal musical training a chance to perform on a wider stage. The height of their fame was this recording, made in the Free Trade Hall on June 19th 1929 with the Hallé Orchestra and Hamilton Harty conducting. It was an immediate popular success and has remained in the catalogue ever since, officially achieving Gold Disc status in 1989.

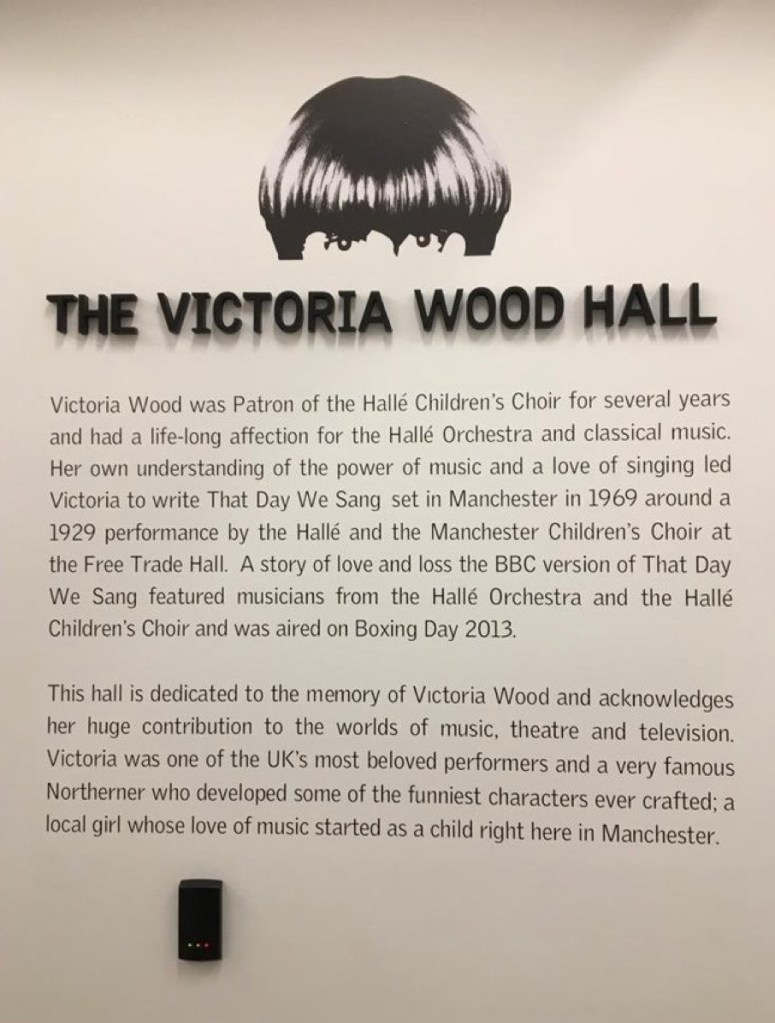

In 2011. more than eighty years after the recording, the much-missed songwriter/comedian Victoria Wood created a musical based on an imagined reunion between former singers in the choir sometime in the 1970s that she entitled That Day We Sang. It had a successful run at the Manchester Opera House in 2011 as part of the Manchester International Festival with the Hallé Youth Orchestra playing and singers once again drawn from various Manchester primary schools. It was revived a couple of years later at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester, and at the end of 2013 it was turned into a TV film with Imelda Staunton and Michael Ball playing the parts of two of the singers reuniting in middle age. For this production the original recording was reproduced using the voices of the Hallé Children’s Choir. This cemented the link between Victoria Wood and the Hallé and when a new block was added to the Hallé’s rehearsal and recording venue at the old St. Peter’s Church in Ancoats in 2019 with partial assistance from the Victoria Wood Foundation, the new recital room within the complex was named the Victoria Wood Hall. This has been used since then as a rehearsal space for the Hallé Children’s Choir, as a breakout room for sectional rehearsals involving the Hallé Choir’s tenors and basses, and occasionally for that most nerve-wracking of activities, the auditioning of new choir members and the re-auditioning of existing members!

John Barbirolli

Harty resigned as chief conductor of the Hallé in February 1933 after a number of less than harmonious disputes with the Hallé Concerts Society. He was replaced first by Thomas Beecham and later in 1939 by Malcolm Sargent, but neither oversaw any recordings with the Hallé Choir. The choir’s recording career, which appeared to have been almost stifled at birth following the release of By the Wayside, was only revived with the arrival in 1943 of John Barbirolli and the ushering in of what proved to be a new golden age for the orchestra. His journey to Manchester was fascinating. He was born in Holborn in 1899, the son of an Italian father, who had played in the La Scala orchestra for the first performance of Verdi’s Otello, and a French mother. The young Barbirolli was something of a prodigy, making two acoustic recordings for Edison Bell with his sister in 1911 and in 1916 becoming the youngest ever member of Henry Wood’s Queen’s Hall Orchestra. After service in the latter part of the Great War, where he first tried his hand at conducting with an army orchestra, he plied his trade through the 1920s both as a freelance cellist, and increasingly as a conductor, particularly in the world of opera with the British National Opera Orchestra. By 1927, now a fully-fledged conductor, he was receiving his first recording contract. His fame really exploded in 1936 when what was meant to be a short-term engagement with the New York Philharmonic, from whom the legendary Arturo Toscanini had just departed, turned into a six-year stint as their chief conductor. Returning to England he received an invitation in early 1943 to take on the Hallé, and over the next 25 years built it up from the small rump of musicians that he inherited when he took over into a truly world-class orchestra that was especially renowned for its recordings, of which a small but significant number would feature the Hallé Choir.

1949 – These Things Shall Be

1948 saw the most significant breakthrough in sound reproduction for nearly 50 years with the development of the first 12 inch long-playing record by the Hungarian electrical engineer Peter Goldmark. He was working Columbia Records in the USA which by that time had no connection to the Columbia label in the UK that was involved in the creation of EMI. The new microgroove format could be played at a much slower speed (33 1/3 rpm rather than 78 rpm), and as result could hold much more music, initially up to 21 minutes per side. The new records were also made of a mixture of vinyl chloride and vinyl acetate that was harder, finer and less easy to break than the old shellac 78 rpm records. Around the same time RCA developed the first 45 rpm 7 inch record that of course went on to be the standard format for the burgeoning pop music industry.

However, despite this new emergent technology, when the Hallé Choir came to make what was only their second recording in May 1948, the EMI label His Master’s Voice was still resolutely in the 78 rpm shellac era. The conductor for the new recording was or course Barbirolli, and the work chosen to be recorded was John Ireland’s These Things Shall Be for baritone or tenor soloist (in this recording, tenor Parry Jones), choir and orchestra. The work had been commissioned by the BBC as part of the celebrations of the coronation of George VI in 1937 and was a setting of part of a poem by J. Addington Symonds that celebrated the rebirth of a nation after a period of hardship, thus making a particularly apposite work to record in the immediate aftermath of the ravages of the Second World War. It was also made up of four short sections such that it could fit neatly onto the four sides of two 78 rpm records.

The recording was made not in the Free Trade Hall, but in Houldsworth Hall on Deansgate. Houldsworth Hall was contained within Church House, opened in 1911 as the administrative centre for the Diocese of Manchester, and whilst it was mainly used for church functions, it was also used extensively for musical events, from classical (for example, concerts by students of the Northern School of Music), jazz (Earl Hines in 1965), progressive rock (Caravan in 1970) and even punk (Generation X in 1976). On the 1st of May 1948, however, it was very much Hallé territory as the EMI produce Lawrence Collingwood recorded the choir (trained by this time by Herbert Bardgett) as Barbirolli conducted the Ireland piece, with the resultant recording being released early in 1949.

Listening to the LP recording now, it is obvious that recording quality had vastly improved in the twenty years since the choir’s first recording. The sound is much fuller and broader with good balance between the choir and orchestra except in the loudest passages where the top end is a little compressed. It is fascinating to hear the evolution of the sound of the choir. The tendency to swoop is still there, but less pronounced and restricted mainly to the tenors and basses, though there is much more vibrato coming from the sopranos and altos than would be normal in a modern recording. Most noticeably, any trace of Mancunian vowels have largely been submerged under layers of BBC-style received pronunciation, and the words themselves become indistinct once the dynamic rises above mf. Sadly, to my ears at least the work itself is not instantly memorable, with the choral line stridently, even relentlessly, homophonic until at change in tone with the entry of the tenor soloist (whose vowels are deliciously mangled!) leads to a softer conclusion.

That said, the review by ‘T.H’ in The Gramophone was very complimentary, praising both the attack and the choral tone which had ‘a fullness and depth which are most satisfying’. He also praised the diction, a sentiment with which, with 21st century hindsight, I would quibble. He spotted the problem with the louder sounds, which he attributed to technology still being unable to cope with ‘big choral recordings’ (which this most definitely is following the more intimate nature of the choir’s first recording), but overall considered it ‘a very worthy performance and recording of some fine music’. The reviewer in Tempo magazine felt that the recording deficiencies ultimately let down the recording, writing that ‘the strong, emotional quality [of the work] has certainly been felt by all performers with the consequence that the spirit of the work is maintained at the expense of other details which, otherwise, would have been this a very fine recording’. The reviewer particularly notes problems with the choral enunciation and the ‘lack of a consistently good balance’.

Note that if you want to hear a cleaned-up version of this recording, the Barbirolli Society have reissued it on a CD (The Barbirolli English Album – catalogue no. SJB 1022), but it isn’t available on any of the streaming services. I have therefore provided a link below to the 1990 Richard Hickox recording of the work for Chandos so you can at least hear what the piece sounds like.

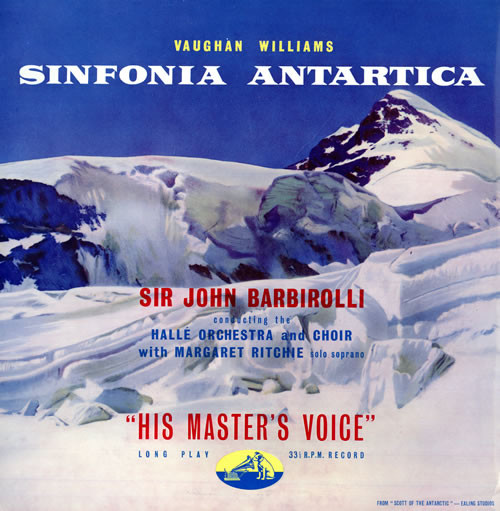

1954 – Sinfonia Antartica

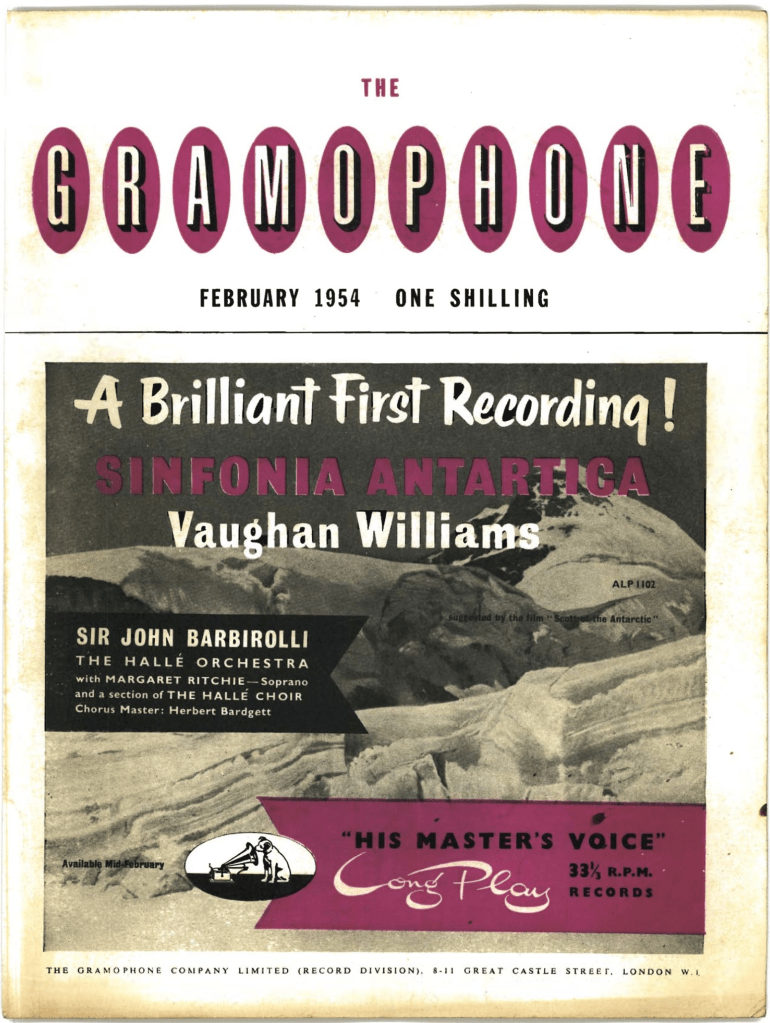

In my earlier blog about the relationship between the Hallé Choir and Ralph Vaughan Williams, I described the origins of that composer’s seventh symphony, the Sinfonia Antartica, and how the Hallé under Barbirolli gave it its first performance at the Free Trade Hall in January 1953, assisted by soprano Margaret Ritchie and the sopranos and altos of the Hallé Choir in an evocative wordless choirs that echoed the snowy wastes of Antarctica. What I did not then go on to describe was how the same forces reassembled in June of that year to make the premiere recording of the piece. By now the Hallé had embraced the microgroove revolution and when the recording was released early in 1954 it was on a single 33 1/3 rpm long-playing record complete with a cover painting of an icy landscape.

The press reaction to the concert premiere of the piece had been very favourable, and the same was largely true when the critics came to review the new LP. The reviewer for The Gramophone felt the ‘unusual colouring [of the symphony was] very faithfully captured’ and the the performance of Barbirolli and the orchestra was ‘very clear and well-toned’, though there were complaints about a degree of boxiness in some of the louder passages and some quibbles about the choral and orchestra fadeout at the end of the symphony, particularly with regard to the wind machine. However, the overall verdict was that it was ‘a first-class recording of an immensely moving work’.

There was no specific mention of the quality of the chorus in the Gramophone review but Dyneley Hussey in The Musical Times wrote that ‘the small women’s chorus is given exactly the right distant effect’. Both reviews praise Margaret Ritchie. Hussey wrote ‘Miss Ritchie sings her wordless music perfectly and creates the impression of a disembodied voice’. In summary, he felt the recording to be ‘a splendid addition to the library of contemporary music’.

In researching this blog I managed to get hold of an original copy of the LP from 1954, and it was fascinating to compare this with the cleaned-up digitally remastered version that was released on the Apple Music streaming platform in June 2020. Even allowing for the inevitable surface noise present on the nearly 70 year old vinyl record, the LP sounds hemmed in, with little of the dynamic range that this piece deserves and that was fully present on the 1970 recording by Adrian Boult that gave me my first introduction to the piece, in particular the cataclysmic entry of the organ in the Landscape section of the symphony, which even on our budget family stereo completely blew me away. In contrast, the remastered version seems to have opened out the orchestral sound, giving it a much greater depth and clarity. This exposes a few minor infelicities in the orchestra but overall it sounds like a complete different recording. I would urge you to give a listen – the relevant link to Spotify can be found below. What is particularly gratifying is how good the female chorus sound. The voices are beautifully blended with most hints of the excessive vibrato that coloured the Ireland recording removed, perfectly evoking the other-worldly effect that Vaughan Williams was after. However, I would agree with the Gramophone that the final fade-out could have been more finely judged.

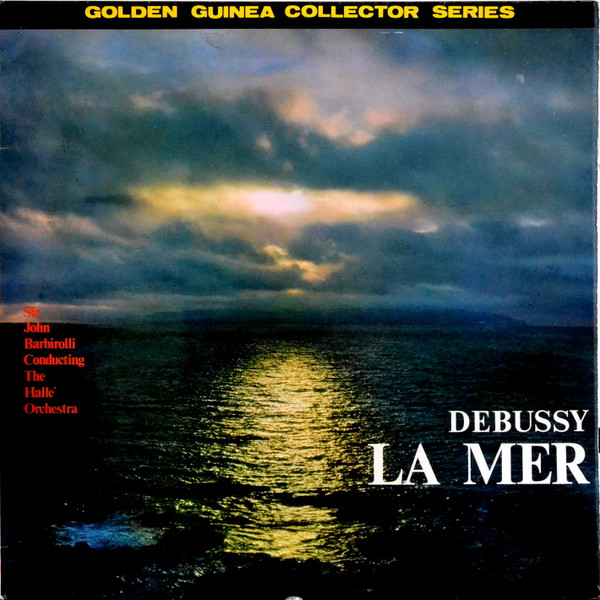

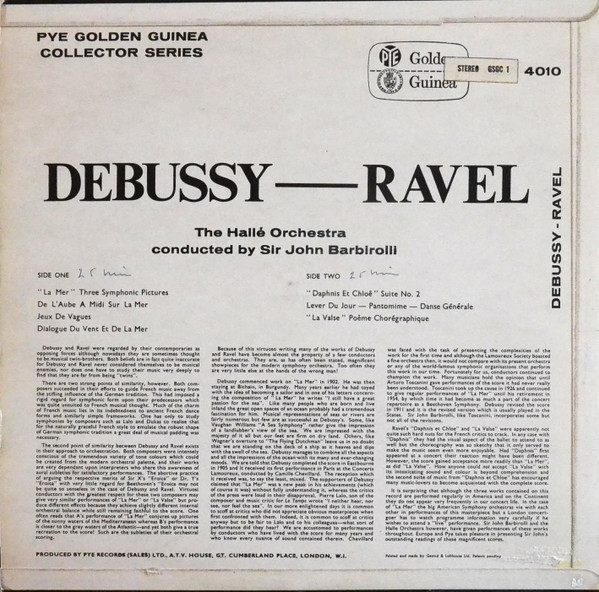

1964 – Daphnis and Chloe Suite No. 2

The late 1950s saw a further revolution in recorded sound. Record companies had been experimenting with stereophonic sound, that is the playback of a sound recording through two separate and distinct channels thus giving the listener an impression of the width of an orchestra or band, since the 1930s. In the early 1950s stereophonic tape recorders and players began to be produced, but it was not until stereophonic sound began to put within the grooves of an LP in 1958 that ‘stereo’ sound, as it came to be known, began to take off. For a long time record companies would produce both monophonic and stereophonic versions of new LP releases but eventually the stereo format won out and is still, despite the recent incursions of surround sound technology, the standard format music is listened to today. By this time recordings were also made onto tape which meant that many different performances or ‘takes’ could be recorded. Bits of different takes could then be cut up and pasted together, or ‘patched’, to form the final performance that would be transferred to vinyl. One trick in listening to old recordings from this pre-digital era is seeing if you can work out where the patches are – they are unfortunately often very obvious! Advances in technology also meant that the tape would also be made up of multiple tracks onto which different parts of the orchestra and choir could be recorded. These tracks could then be mixed together into the final stereo mix.

The first time the voices of the Hallé Choir were heard in stereo came in 1964 with the release of Barbirolli’s recording of the second of the suites Maurice Ravel compiled from his ballet score Daphnis and Chloe. In my humble opinion the full ballet score is the most beautiful hour of classical music ever written, and the Suite No. 2 captures that beauty, beginning with the ecstatic orchestral build-up of the ‘Dawn’ sequence from the second half of the ballet that culminates in a glorious wordless choral outburst that is one of the wonders of early 20th century music.

According to the discography in Michael Kennedy’s biography of Barbirolli the recording sessions for this album, which also included Debussy’s La Mer and Ravel’s La Valse, took place in the Free Trade Hall in September 1959. However, there is no record of it being made available commercially before 1964, when it was released on Pye’s budget Golden Guinea label. There is also confusion regarding the recording of the suite attributed to the Hallé and Barbirolli that has been made available on Spotify, with some online chatter that though the conductor is Barbirolli it might in fact be a recording he made with an American orchestra at around that time. Therefore, while I provide the link, I will make no comment on the musical content therein!

However, I will make mention of the review in The Gramophone, which is a distinctly glowing one. The reviewer, making reference to its low price, starts by saying ‘this is a winner, if ever there was one – at any price’, and talking about Barbirolli says ‘here is a genius of a conductor getting superb quality from the players under him, performances of real mastery…”. Sadly, the only mention of the choir is simply one that ‘there is a chorus in the performance, as in the original ballet score’. That probably needed to be said as there is actually no mention of the choir on the album sleeve itself.

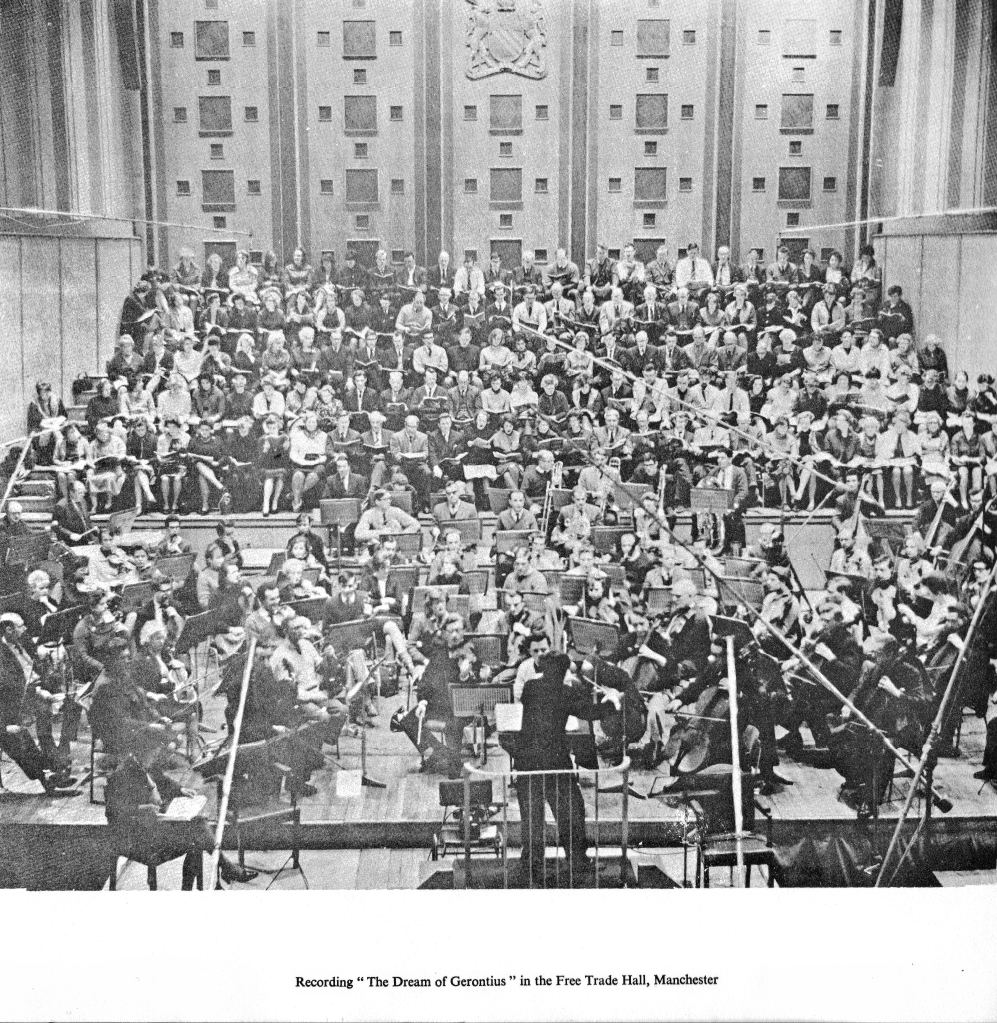

1965 – The Dream of Gerontius

There is no such confusion about the next recording involving the Hallé Choir, as it is possibly one of the most important recordings the choir has ever made. This was the 1965 release of Barbirolli’s recording of Elgar’s choral masterpiece The Dream of Gerontius. Barbirolli had conducted Gerontius many times before, and especially helped popularise the work in the USA – there is indeed a CD available of a recording of the work that he made for PBS with the New York Philharmonic in 1959. However, it wasn’t until 1964 that Barbirolli felt ready to commit the work to vinyl in proper studio recording conditions.

It was obviously a work that meant a great deal to Barbirolli. In a fascinating brief essay that accompanied the LP Box Set of the recording, he talked of receiving the blessing of Pope Pius XII after a performance of the first part of Gerontius that he conducted at the Pope’s summer residence Castel Gandolfo, and reminisced about playing the work under Elgar in Worcester Cathedral as part of the first Three Choirs Festival after the First World War in 1919. He remembered with special poignancy the performance with the Hallé Orchestra and Choir at the Edinburgh Festival in 1950 that proved to be the last time Kathleen Ferrier ever sang Gerontius. His final words sum up his feelings about the work, as well as expressing gratitude that he was recording with EMI again after a period with Pye: ‘I am profoundly grateful to E.M.I. for granting me the privilege of recording, with such loyal and sensitive colleagues, this great work which I love so deeply’.

The recording was made in the Free Trade Hall, and is perhaps most remarkable about it is the timing of the recording sessions – they took place between the 27th and 30th December, 1964. These days, with the audience revenue available from festive concerts, it would be highly unlikely that the Bridgewater Hall would be free for such a long period at such a time. Indeed, December 2023 sees two Hallé concerts on the 29th and 30th. Even so, I’m sure the choir were given strict instructions by chorus master Eric Chadwick to go easy on the sherry and mince pies on Christmas Day and Boxing Day! The Hallé Choir were bolstered for the recording by two further choirs, long-standing collaborators the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus, for whom Eric Chadwick was also chorus master, and the small professional choir, the Ambrosian Singers, who took the part of the semi-chorus. The soloists were a stellar bunch – the Mancunian tenor Richard Lewis, the Finnish bass Kim Borg, and mezzo-soprano Janet Baker, at the time one of the most loved singers in the UK, still fondly remembered following her early retirement but thankfully very much still with us.

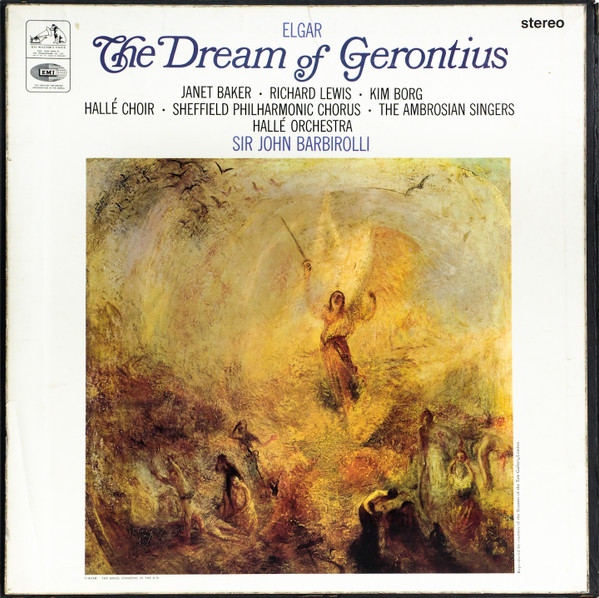

The recording itself was released in late 1965 on the HMV label, with 2 LPs inside a presentation box that was adorned with Turner’s painting of ‘The Angel Standing in the Sun’ and was accompanied by a lavishly illustrated booklet that included all of the words of the oratorio, the above-mentioned essay by Barbirolli, and an analysis of the score by Eric Robertson. It was quite the luxury production and was obviously considered a hallmark release by EMI.

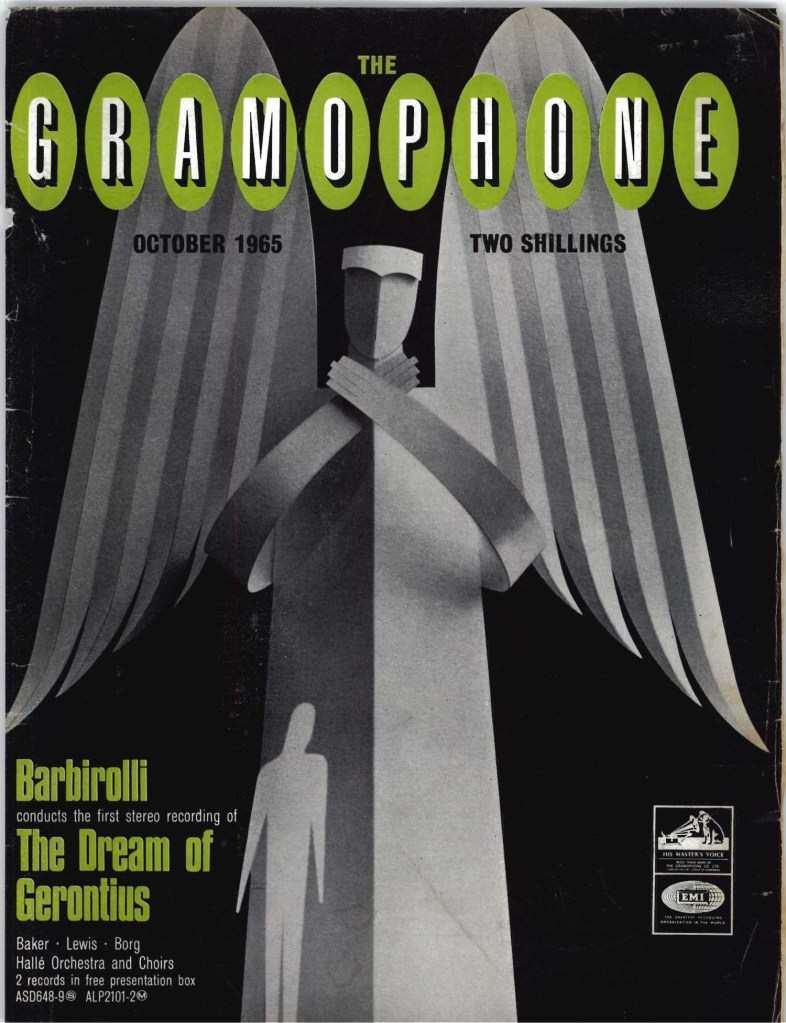

The review in The Gramophone gives the fullest account yet of the recorded sound of the choir. This passage first compares the choir’s rendering of the famous Demons’ Chorus to the then recent recording by Malcolm Sargent, in which the reviewer considered the chorus ‘more bad-tempered than demonic’:

The combined Hallé Choir and Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus, spurred on by Sir John Barbirolli, make a great success of it. They sing it with more venom than I have ever heard, and pay proper attention to their consonants in such phrases as “Dispossessed, chucked down”; even their “ha ha’s” are as convincing as this absurd exclamation, in the context, can be.

Extract from review of Gerontius recording in The Gramophone – October 1965

Further comments are not quite so complimentary. Although the reviewer thinks the chorus are ‘at their best at the end of Part 1 and in the tremendous hymn “Praise to the Holiest’, there is criticism for some of the other singing in Part 1 which ‘sounds a little tentative’. Richard Lewis as Gerontius gets warm praise – ‘he lives intensely through the great drama, and none of the many sublime moments of the part find him wanting’. Whilst Kim Borg singing is ‘expressive’ the reviewer reserves judgement on whether it was right to have a non-English speaking singer in the parts of the Priest and Angel of the Agony, but has no reservations at all about Janet Baker for whom ‘no praise can be too high. She simply is the Angel, with an other-worldly aura about her singing from the first note to the last’. The reviewer finishes by praising ‘Barbirolli’s movingly beautiful interpretation of the work and Janet Baker’s superb singing of the Angel’.

Edward Greenfield, reviewing the recording in the Guardian, is equally fulsome in his praise. He also notes the ferocity of the demons: ‘If anyone has ever complained that Elgar’s demons are half-hearted, less than diabolic in their cries of “Ha-Ha!”, let him hear the Hallé Choir and Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus snarling in bitterness’. He is slightly concerned about the balance of the Ambrosian Singers as the semi-chorus against the other forces but otherwise thinks ‘the choral sound is rich and beautiful’. There is praise for Richard Lewis, and slightly less for Kim Borg (‘virile in tone, but with a depressing reluctance to sing softly’), but the main plaudits are again for Janet Baker: ‘Once again Miss Baker’s natural dominance as an artist makes one hear every phrase as though newly composed’.

Finally in terms of reviews, Wilfred Mellers, writing in the Musical Times, is the dissenting voice. Whilst he feels Barbirolli’s direction ‘ought to be wonderful, for he knows and loves the work’, and whilst ‘the fervent moments are often superb’, what he believes is missing is ‘the occasional glimpse over the horizon that Elgar achieved from within his humanist’s passion’. However he is one more reviewer blown away by Janet Baker’s Angel, ‘which I cannot imagine ever being more radiantly and celestially sung, and with precisely the right degree of human expressiveness’. As for the chorus there is but one brief mention: ‘The combined choruses sing thrillingly in the ecstatic passages, and do the best they can for the devils’.

Back in October 2006 my brother Andrew was tasked with listening through all of the then available recordings of The Dream of Gerontius for an edition of Radio 3’s Building a Library devoted to the work. I remember him telling me that the complexity of the work is such that there probably isn’t any such thing as a perfect performance of Gerontius – in the Barbirolli recording the obvious weak link is Kim Borg. However, in the final analysis (and it took him an agonisingly long time to decide) he took the decision that the high points of the Barbirolli recording, particularly Janet Baker’s singing, so outweighed the low points that it was the obvious choice as his top recommended recording. When the work came up again in 2017, the reviewer Mark Lowther made the Vernon Handley recording with the RLPO his top choice, relegating the Barbirolli recording to one of this two alternative choices, the other being Mark Elder’s later recording with the Hallé which I will talk about in Part 3 of this blog.

In researching this blog I was able, as with Sinfonia Antartica, to compare the original LP sound with the digitally remastered version available on the streaming platforms. Listening first to the digital version, the first thing that hit me was how modern the recording sounds, at least orchestrally. It is remarkable to think that a little over 40 years earlier the young Barbirolli was making his first recording through an acoustic horn onto a wax cylinder, given how full and rich the orchestral sound is here. Janet Baker sounds magnificent on the recording – a true mezzo-soprano, deep and mellow at the contralto end of her range that she occupies most of the time, but bright and clear when she approaches the soprano end of her range, as in the passage that leads up to the first full-choir rendition of the words ‘Praise to the Holiest’. Richard Lewis sings with a pleasingly consistent tone, if a bit pinched when singing quietly. My brother tells me he heard from Michael Kennedy was suffering from a cold at the time, a fact that is hinted at also in the Gramophone review, but there is no sign of that in the recording. Kim Borg’s singing is perfectly adequate. His main problem is his vowels – it is a real shame that Elgar set the word ‘name’ so often and so prominently in the passage that the Priest sings in the first part of the oratorio, as Borg mangles it every time!

As far as the choral singing is concerned, a first listen bears out Edward Greenfield’s comment about the Ambrosian Singers who formed the semi-chorus, as they are far too far back in the mix in their contributions to Part 1 of the oratorio. In Part 2, where the women from the Ambrosian Singers sing the semi-chorus of Angelicals, they sound much more matronly than angelical, meaning that the mix with the purer sound of the main chorus is not all it could be. Other than that the contributions of the main choir are in the main part extremely effective. Yes, to a modern ear the vowels sound extremely mannered, but if you listen to other choral recordings of the time there are far worse examples of choral Received Pronunciation. The basses occasionally get lost in the mix, such as in the ‘Rescue Me’ section where their first entry doesn’t punch through as it should, but there sound is generally well blended, unlike the tenors where a couple of stray individual voices are persistently heard above the rest of the section. Again though, these are minor quibbles. The only point where things go astray is in the meditative section after the first full-choir outburst of ‘Praise to the Holiest’ that begins ‘O loving wisdom of our God’. In the score, the music slows marginally but is still marked allegro molto, but Barbirolli slows the tempo right down so that by the time the choir get to sing ‘O generous love’ they are hardly moving. This gives the choir a chance to wallow, and unfortunately they do! It also means the choir are a little bit too slow at the point at which they start the rush to the fff end of this particular section, and Barbirolli is not able to ramp up the excitement as much as he could do because he simply runs out of road.

Listening to the LP version of the recording, a lot of the contrast that was added to it in the digital mastering is missing but the recorded sound still feels far superior to the sound quality present on the Sinfonia Antartica recording – much more alive and present, and far less contained at both to the top and bottom ends. All in all it is an impressive recording in whatever format you choose.

This was the last recording Barbirolli made with the Hallé Choir, and after suffering a series of heart problems during the preceding months, he died of a heart attack on July 29th 1970, at the age of 70. He became associated with the Hallé in a way that no other conductor other than Charles Hallé has, though it’s probably true to say that Mark Elder will be looked at in a similar light when he finally steps down as chief conductor in 2024. Like Barbirolli, Elder has taken the orchestra back to its roots, particular its deep roots in the music of Edward Elgar, as we shall see in Part 3 of this blog. In the meantime, Part 2 will look at the remarkably eclectic range of music that the choir recorded between the departure of John Barbirolli and the arrival of Mark Elder.

One final note: it’s not the last we shall see of Barbirolli in this blog. In more recent times a couple of CDs have been released of live recordings made for the BBC and as I’m looking at the choir’s recordings in release order I shall look at those at the relevant point in the timeline where they were released.

References:

Guardian and Manchester Guardian archive, courtesy of Manchester Libraries

Musical Times archive, courtesy of jstor.org

Tempo magazine archive, courtesy of jstor.org

The Gramophone magazine archive, courtesy of gramophone.co.uk

Anon, Discography of American Historical Recordings – Hamilton Harty, (UC Santa Barbara Library) <https://adp.library.ucsb.edu/index.php/mastertalent/detail/103404/Harty_Hamilton?Matrix_page=100000>

———, The Dream of Gerontius Discography, (Wikipedia) <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Dream_of_Gerontius_discography>

———, The history of 78 R.P.M. recordings, (Yale University Library Irving S. Gilmore Music Library) <https://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/music/historyof78rpms#:~:text=The%20electrical%20era%3A%201925–47&text=After%20about%201925%2C%2078s%20were,are%20called%20%22electrical%22%20recordings.>

———, Northern School Of Music (NSM), Houldsworth Hall 1950, (Manchester Digital Music Archive, 2020) <https://www.mdmarchive.co.uk/artefact/22193/NORTHERN_SCHOOL_OF_MUSIC_(NSM)_HOULDSWORTH_HALL_PHOTOGRAPH_1950>

———, ‘Sir Hamilton Harty and the Hallé Orchestra’, The Phonograph Monthly Review (May 1927).

———, Stereophonic Sound, (Engineering and Technology History Wiki) <https://ethw.org/Stereophonic_Sound>

Tony Burke, Houldsworth Hall (90 Deansgate), (Manchesterbeat) <https://manchesterbeat.com/index.php/venues/venues-manchester-cbd/houldsworth-hall-manchester>

Colin Charnley, Electrical 78rpm recordings, (Archive of Recorded Church Music) <https://recordedchurchmusic.org/electrical-78-s-1926-1957>

Simon Heighes, Wax cylinders: what they are and how they revolutionised music in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, (Classical Music, September 28, 2021) <https://www.classical-music.com/features/articles/wax-cylinders-what-they-are-and-how-they-revolutionised-music-in-the-late-19th-and-early-20th-centuries/>

Michael Kennedy, Barbirolli: Conductor Laureate; The Authorised Biography (London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1971).

———, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960).

———, The Hallé: 1858-1983 : A History of the Orchestra (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1982).

John F Russell, ‘Hamilton Harty’, Music and Letters (July 1941).

Bob Stanley, Let’s Do It: The Birth of Pop (London: Faber & Faber, 2022).

David Ward, ‘Victoria Wood recalls a historic day for Manchester’, The Guardian, June 30th, 2011.

Leave a reply to On Record – Part 4: The Mark Elder Years 2013 – 2023 – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply