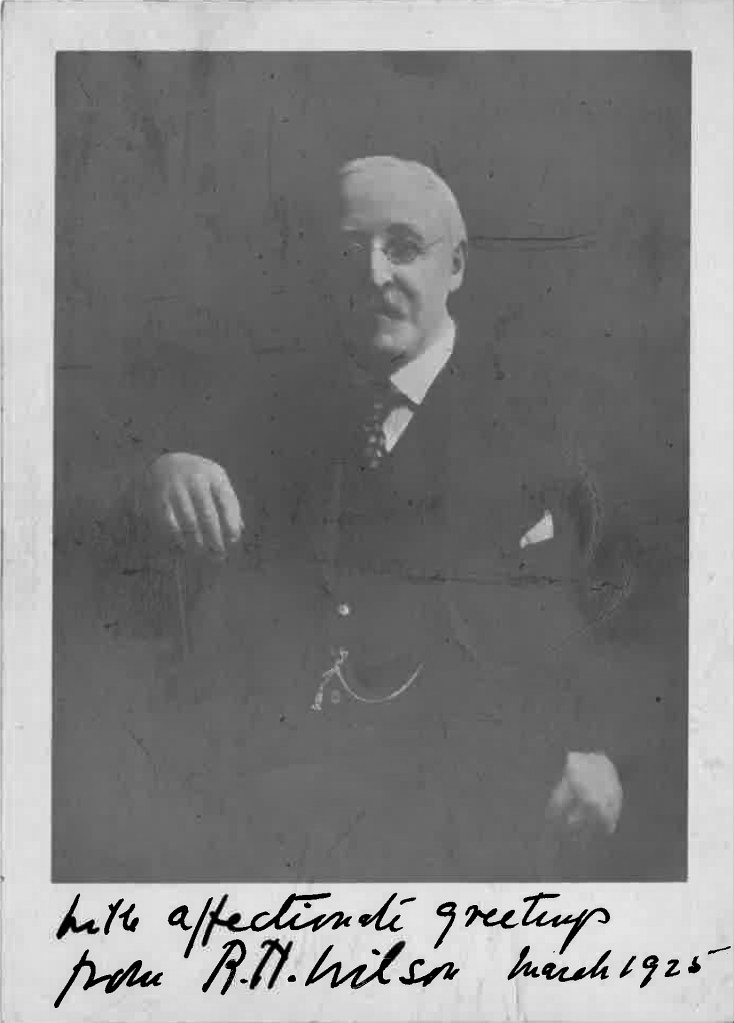

The Hallé Choir has had remarkably few choral directors in its 165 year history. For example, the first 67 years of the choir’s existence saw just three, one of whom only served for a couple of years. Edward Hecht, the man Charles Hallé himself picked to lead his nascent chorus, served from the choir’s foundation in 1858 until 1887. There followed a brief interregnum where Hecht’s fellow German Adolf Beyschlag took temporary charge. 1889 saw the appointment of the man who would lead the choir through the fading years of the Victorian era and through two exhausting wars to the heart of the Roaring Twenties in 1925, making him by some distance the longest serving director in the choir’s history. This man, known to all but his closest acquaintances as R.H. Wilson, is the subject of this blog.

Robert Henry Wilson was born in Manchester in 1856, the year before the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition that led to the formation of Charles Hallé’s orchestra. He appears to have been the only surviving child of his Yorkshire-born father Robert senior, a draper, and his mother Eliza. In 1871, they were living in Rochdale Road in the St Michael’s Ward of Manchester and thus only a short walking distance from St Peter’s Church in Ancoats, where the choir he was later to direct now rehearse. Though they were not in the smartest area of town the Wilson family were wealthy enough to afford a live-in servant. Remarkably, though he was only 15, the young Robert’s occupation is already shown as ‘organist’.

Obviously exhibiting musical talent at a young age, he began to study under Sir Frederick Bridge, who was organist at Manchester Cathedral from 1869 to 1875 before moving to become organist and choirmaster at Westminster Abbey and a teacher at the newly formed Royal College of Music. This study may have taken place at Owens College, the predecessor institution to the University of Manchester, where Bridge had become professor of harmony in 1872. Wilson moved on to gain a Bachelor of Music degree from Oxford, and would from this time forward term always term himself as a ‘Professor of Music’ in census returns.

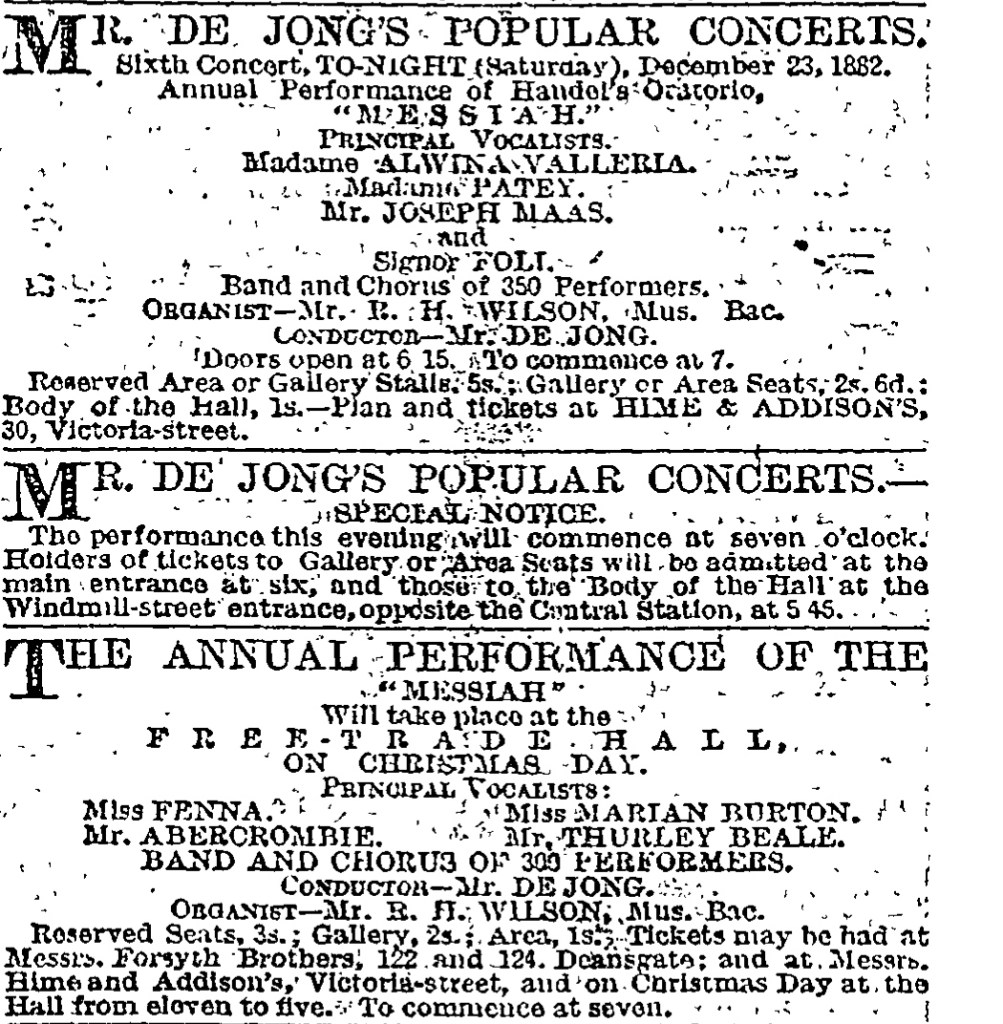

Wilson first described himself thus in the census return for 1881 which saw him lodging with one Margaret Banks in York Street, Cheetham, which was renamed Cheetham Hill Road in 1900 and was then, as now, one of the most diverse and eclectic streets in Manchester. The following year saw him performing as organist for two performances of Messiah for the Dutch conductor Edward de Jong, one of which was actually on Christmas Day in the Free Trade Hall.

De Jong was a former flautist in Hallé’s orchestra who had left in 1871 to set up a rival series of concerts of a more popular nature which he advertised, logically, as ‘Mr de Jong’s Popular Concerts’. Wilson’s participation in these concerts is evidence that he was making a name for himself in the Manchester musical and choral establishment

Wilson was obviously also attracting the attention of Charles Hallé, who at 70 was nearing the end of his time with the orchestra and choir he had founded. An editorial in the Manchester Guardian in November 1889 extolled the benefits to Manchester of the Hallé Orchestra and Choir: ‘In no other city of the kingdom do amateurs enjoy such musical privileges as we have now possessed for more than a generation. Week after week we have the opportunity of hearing either a great choral work performed by a fine choir and eminent principal vocalists, or a series of orchestral works of not less commanding interest’. That ‘fine choir’ was now directed by Mr de Jong’s former young organist, R.H. Wilson, who had taken over from Adolf Beyschlag at the beginning of the 1889/90 season.

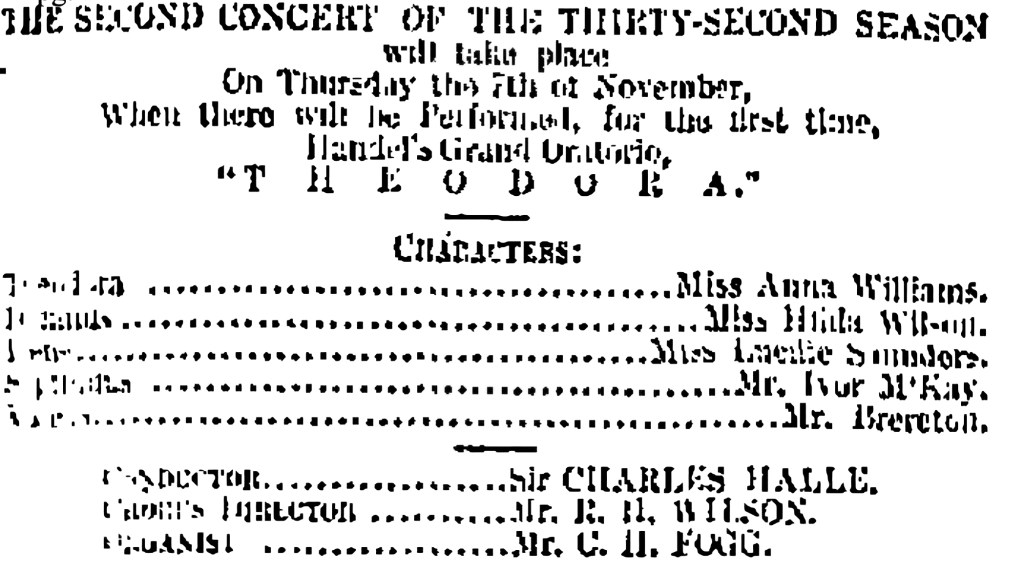

The first works he prepared are mostly rarely heard today, beginning with Handel’s oratorio Theodora on November 7th, a work being performed according to the Guardian in a preview article ‘if not for the first time in Manchester, certainly for the first time within the recollection of the oldest amateur’. Their later review of the concert questioned ‘how it has experienced such undeserved neglect’, as ‘its attractions for choralists alone would have sufficed to make it popular’, and ‘the interest of the choruses is, indeed, unique amongst the works of Handel’. Having said this at the top of the review it is perhaps surprising that the reviewer leaves it to the very end to make mention of the chorus, but when he does it is obvious that the new young chorus master has done his work well: ‘The choruses were capitally given, the work of rehearsal having evidently been thoroughly performed by the new chorus master, Mr. R.H. Wilson. The whole work met with a degree of appreciation which proved that there was an unusually critical and discriminating body of musical amateurs present’.

Wilson’s next concert in charge, on November 29th, brought the choir together with one of the major musical figures of the late 19th century. Sir Arthur Sullivan is known today more for his comic opera collaborations with W.S. Gilbert than for the concert pieces that he himself would rather have been remembered for. Sullivan had been engaged to conduct the choir in his cantata The Golden Legend, a piece now lost to history apart from a very few recordings of small sections of the cantata, but at the time being sung by the choir for the third time. The work itself was based on Longfellow’s poem of the same name and after its first performance at the Leeds Festival in 1886 was performed frequently not just by the Hallé but by choral societies throughout the country. The Guardian reviewer of the 1889 concert was of the opinion that ‘every new hearing of it confirms the opinion more than once expressed, that in this noble and beautiful cantata Sir Arthur Sullivan is heard at his best’. Sullivan would have loved those words, but history has been less kind.

The reviewer quoted Sullivan as saying that the performance by the choir was ‘certainly as refined and poetical a working of his work as any he has ever heard’, and that ‘this very complimentary verdict is very creditable to Sir C. Hallé’s fine choir, and certainly not less so to the chorus master R.H. Wilson’. Wilson was obviously getting his feet well under the table and was working the choir hard – this very concert alone also included the choir singing Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia with Hallé playing the virtuoso piano part and conducting, along with the Pageant March for Orchestra and Chorus from Gounod’s now neglected opera La Reine de Saba. And of course only a couple of weeks later Wilson was preparing the choir for their traditional two performances of Messiah.

Wilson’s arrangements had changed significantly by this time, professionally, financially and domestically. The 1891 census shows him living in middle class comfort in Swann Lane, Cheadle Hulme, married to his wife Ada, with a two year old son Harold, a one year old daughter Norah, and two live-in servants. Wilson was obviously gaining a reputation. This is reflected in the review for a concert in 1893 where the Guardian critic proclaimed that ‘one of the finest performances of the “[Rossini] Stabat Mater” ever heard in this city was due to the choir and their excellent chorus-master, Mr. R.H. Wilson’.

As I hinted at the top of this blog, Wilson long tenure in charge of the Hallé Choir was played out against a background of tragedy and conflict, both local and especially national. Local tragedy struck two years later in 1895 with the death of the man who had steered the orchestra and choir that both bore his name from their foundation almost forty years earlier. The autumn of 1895 saw Charles Hallé apparently fit and as keen to work as ever. On his return from a trip to South Africa with his wife that summer, his son Charles Jr. declared him ‘full of health and spirits and apparently stronger and better than he had been for some time’. Hallé opened the Liverpool Philharmonic season on October 22nd, and on the 24th rehearsed for the first concert of the Hallé’s Manchester season. That night he sent word to his son that he was ill and soon after suffered a cerebral haemorrhage and died at 10 a.m. on the morning of the 25th without regaining consciousness.

His funeral took place on October 29th at the Catholic Church of the Holy Name, Oxford Road, close to where the Royal Northern College of Music now stands. All of the flags in Manchester flew at half mast to honour the beloved adopted Mancunian, and large crowds gathered in thick fog as the funeral procession was led by some of the tenors and basses of Hallé’s choir. According to Hallé’s own wishes Adolph Brodsky conducted the Hallé orchestra and choir in a performance of Mozart’s Requiem. The Guardian related how, despite the short preparation time Brodsky and R.H. Wilson managed to put together a performance worth of the solemn occasion:

An orchestra of fifty members of Sir Charles Hallé’s band and a chorus of a hundred of his choir occupied the organ gallery. Mr Brodsky conducted the performance of Mozart’s “Requiem” – perhaps the best known of all the great works of the kind, and one, moreover, associated with the great musician in whose memory it was sung yesterday. It is often said that music of this character is heard to finer effect in a great Gothic church than anywhere else; and the circumstances and the solemnity of the occasion yesterday would have given distinction to a far less admirable interpretation of the work than that which was heard.

Extract from a report of Sir Charles Hallé’s funeral – Manchester Guardian, October 30th, 1895

Hallé’s baton passed briefly to Sir Frederic Cowen, also at the time conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (as had been Hallé for a short period before his death). The choir continued to flourish under Cowen, thanks in no small part to the efforts of Wilson, who by now had firmly established himself. A Guardian report of a performance of Elijah in 1897 declares that ‘No small share of the success of this memorable performance was due to the careful oversight of the conductor, Mr. Cowen, and he would be the first to admit that the honours of the evening were largely shared by the choirmaster, Mr R.H. Wilson’.

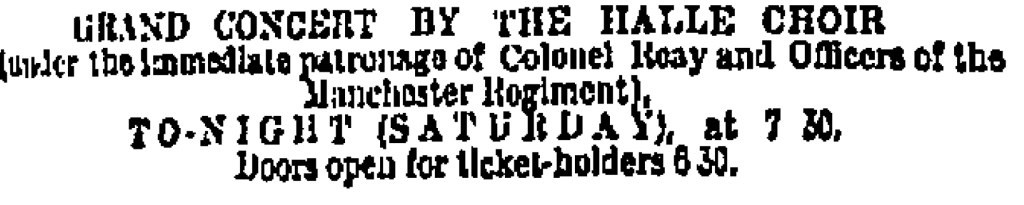

The next 20 years of Wilson’s time with the choir would be marked by war, most notably the carnage of the First World War, but the turn of the century saw the event that presaged that tragic conflict, the dispute between Britain and the Afrikaans-speaking settlers in the South African Republic and the Orange Free State that became known as the Boer War. As with the First World War (at least in its early phases) the Boer War was accompanied by a degree of patriotic fervour that is reflected in a fundraising concert organised in December 1899 which showed an important aspect of Wilson’s association with the Hallé Choir, namely the degree to which he himself would conduct the choir in concert. This particular concert, given in aid of the South African War Fund, took place in a packed Free Trade Hall on the night of December 2nd, with Wilson conducting the choir accompanied by Charles H. Thompson on the organ. This created its own problems with the Guardian stating that Thompson was ‘only moderately successful’, but Wilson and the choir rose to the challenge to deliver an eclectic programme that included Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang, Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens (performed with the orchestra a couple of days earlier), the chorus ‘Hail, Bright Abode’ from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, and ‘The Heavens are Telling’ from Haydn’s Creation. Further vocal items were delivered by the Lobgesang soloists and by the Orpheus Prize Glee Society who sang a couple of items conducted by a Mr. Nesbitt. The audience evidently liked seeing Wilson at the helm in the Hallé Choir items, welcoming ‘the opportunity of paying a tribute to Mr. Wilson, the chorus master, the nature of whose work necessarily keeps him much in the background. He conducted the choral performance most capably’.

The highlight of the evening was a rousing rendition by soloist Gregory Hast of Arthur Sullivan’s setting of Kipling’s Absent-minded Beggar, in which, according to the Guardian, ‘the audience joined the choir in singing the chorus, which was interrupted at every verse by loud applause’. During the singing of the song a hat was passed round the audience for further contributions to the war fund, and at the end of the concert Wilson announced to much applause that a further £50 had been collected, the equivalent of over £5,000 in today’s money.

Wilson may have previously been ‘in the background’, but he was also given for the first time the honour of conducting the choir in their annual performances of Handel’s Messiah, the first of which took place less than three weeks later, on December 21st, 1899. The Guardian reviewer believed that ‘everyone concerned must have been gratified by the decision to invite Mr. R.H. Wilson, the zealous and accomplished choirmaster, to conduct the performances’. The reviewer went on to describe the scene, emphasising the difference that can occur when the person who prepares the choir also conducts the choir:

Mr. Wilson, who was greeted on his appearance with ringing cheers from auditorium and platform, more than justified the confidence of the Committee, and may be congratulated on one of the best “Messiah” performances ever given in Manchester… The choruses of the “Messiah” were probably never more satisfactorily sung here than last night. Perhaps they had been more carefully rehearsed than usual, and probably the choir were specially anxious to do justice to the conductor. However that may have been, there was not only unflagging energy and unfailing accuracy, but, better still, these were accompanied by careful attention to light and shade and to the spirit and sentiment of the successive choruses.

Messiah Review from Manchester Guardian, 22nd December, 1899

Wilson evidently had a taste for the dramatic which was sadly not shared by the reviewer, who felt some of the choruses were taken ‘at a more rapid tempo than that to which we have been generally accustomed’ and regretted that he ‘did not, unfortunately, resist the temptation to produce a sensational but certainly not appropriate contrast at the words ‘Wonderful Counsellor” by taking the opening section of the chorus “For unto us” almost pianissimo’. Maybe Wilson was an early exponent of Historically Informed Performance!

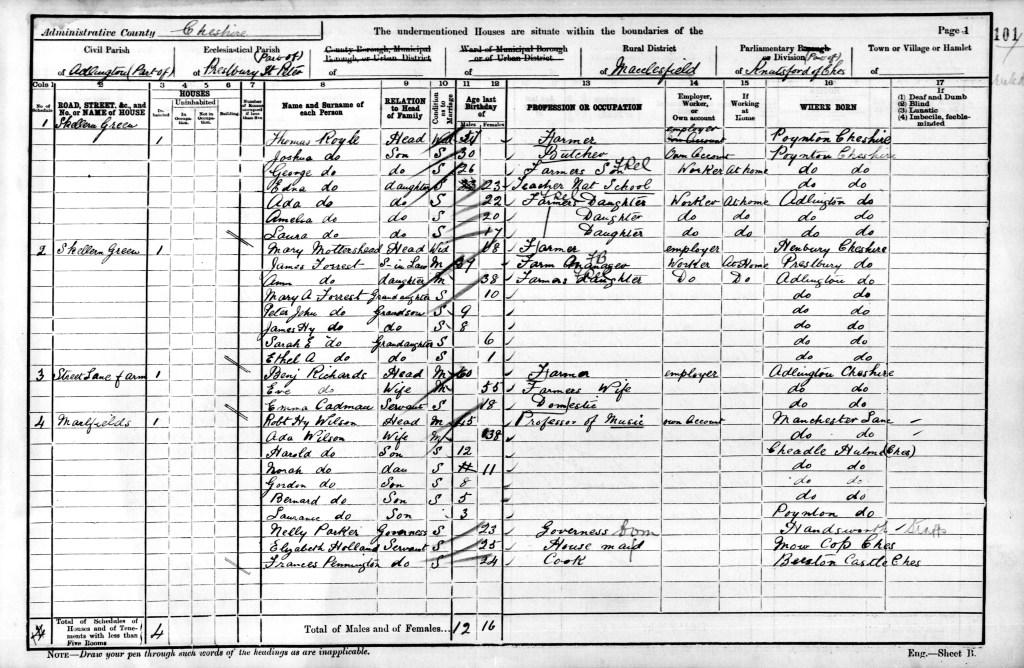

As Wilson’s status within the Hallé organisation grew, so did his family. By 1901 three more sons had arrived, Gordon, Bernard and Lawrence. The family had moved further up-market to the semi-rural setting of Skellorn Green, Adlington, and had not only two servants but also a governess for the children.

Frederic Cowen had moved on in March of 1899 to be replaced by the esteemed conductor Hans Richter. The relationship that developed between Richter and Wilson underlines the value that was placed on Wilson as a choral trainer.

As I described in a previous blog, the first performance of Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius conducted by Richter at the Birmingham Festival in 1900 was blighted in no small measure by lack of preparation on the part of the choir. This was not helped by the fact that the chorus master Charles Swinnerton Heap had died suddenly and the qualities of his replacement, the elderly William Stockley, were not equal to the demands of the music. The first truly successful British performance of the oratorio was that given by Richter and the Hallé in March 1903. Wilson’s preparation of the choir must have impressed both Richter and Elgar because by the time of the next Birmingham Festival in 1903, the preparation for the premiere of Elgar’s new oratorio The Apostles, again to be conducted by Richter, was put in the hands of Wilson. He went on to act as chorus master in 1906 for the first performance of The Kingdom, and for two further Birmingham Festivals.

The Elgar Society’s timeline of the composer’s life shows that Wilson worked closely with Elgar in the final stages of the preparation of the Apostles score. It shows that July 18th, 1903, following a choir rehearsal in Birmingham, Wilson visited Elgar at his Welsh home to go through Part 2 of The Apostles. The following day Wilson got a lift back home along with Elgar’s editor August Jaeger (of Nimrod fame) only for Elgar’s car to break down! Wilson obviously had a galvanising influence on the Birmingham chorus. The Musical Times review of the 1906 festival that included the Kingdom premiere commented that ‘throughout the week [the choir] showed a familiarity with its task, for which R.H. Wilson, the Manchester choirmaster, deserves a chief share of the praise, for he had evidently done his work most thoroughly’.

Wilson’s growing affinity with the music of Elgar manifested itself in a lecture that he gave at the Whitworth Institute in Manchester in the December of 1904 entitled ‘Elgar and the Oratorio’, one of a series that he gave that year. This and subsequent public utterances show that Wilson must have reflected deeply on his craft. In this lecture he contrasted Elgar’s work with that of older composers such as Sullivan and Sterndale Bennett who he believed were too in thrall to a Mendelssohnian model of choral writing, whereas, as the Guardian reporter had it, ‘it had been Elgar’s task to apply to the purposes of oratorio the accumulated musical resources of a century’, epitomised by The Apostles, in which, quoting Wilson directly, ‘music of a modern and revolutionary type is blended with the religious spirit of the Middle Ages’. In this, as with the other lectures he had given, musical examples were given by members of the Hallé Choir, who along with extracts from Gerontius and The Apostles, also sang pieces by Sullivan, Sterndale Bennett and Parry.

Interestingly, that same year Wilson also addressed a subject that has been the bane of many a Hallé Choir member over the years, the re-auditioning of existing members. At the Hallé Concerts Society AGM in June of that year Wilson reported that he had approached the Committee a few months earlier to suggest the adoption the policy that he had recommended when he took over the Birmingham chorus, namely that ‘every voice should be tried’. His suggestion had been adopted and Wilson reported that ‘the work was now nearly over, and the approval of the great majority had been expressed’. He believed that ‘the choir would now be in a finer condition than ever before, and that the valuable results experienced at the Birmingham Festival [in 1903] were likely to be repeated in Manchester’.

Wilson’s association with Hans Richter came to an end with Richter’s departure from Manchester in 1911. Richter’s last piano rehearsal with the Hallé Choir in March of that year ended with him being presented with a silver cigar box by the choir and with many speeches, including one from Wilson that underlined the importance of the relationship of choir to chorus master to conductor. A report of that speech appeared in the Guardian. To begin with it reported that Wilson expressed satisfaction that Richter had the previous week made a confidential statement to the choir about his retirement. Wilson then addressed the choir thus:

“I am sure I express your feelings,” Mr. Wilson continued, “when I say that that loyal confidence has, if possible, drawn you still more closely to him. We have been associated together ten years-(Dr. Richter: Eleven years),-and it is a very significant thing that the very first work the Doctor took with us was Bach’s Magnificat, and the last tonight is Bach’s B Minor Mass. In that time we have had a good deal to do with each other. We have experienced the Doctor’s terrible frown-(laughter),-and we have known the antidote of his most benevolent smile when things have been satisfactory.-(Cheers.) I think I can say for you that you have tried to do the best you can, and that whatever the performances have been you have been always loyal.”-(Cheers.)

Report of presentation by the Hallé Choir to Hans Richter, March 8th, 1911

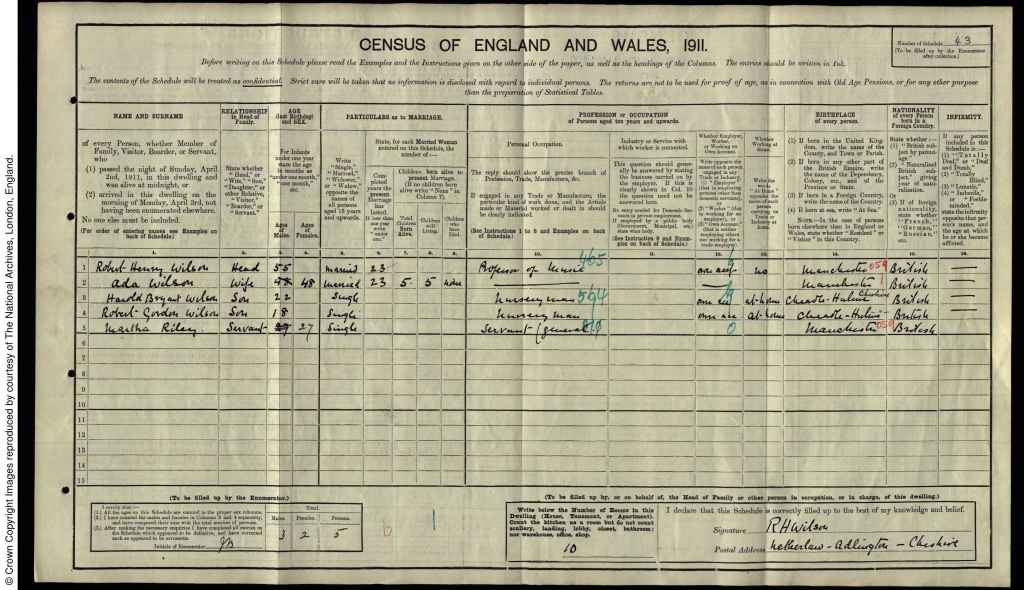

1911 was another census year. Still living in Adlington, as Robert Henry and Ada’s family had grown, so now it shrank, with only the two eldest boys still living at home and the governess long since dispensed with. Now 55, Wilson had been in charge of the choir for 22 years.

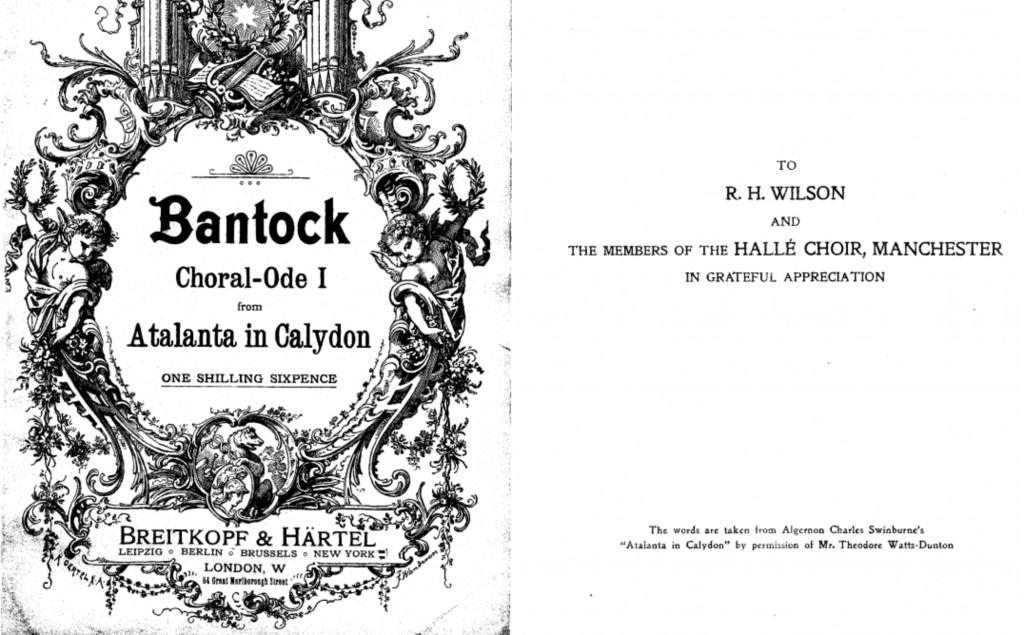

Wilson’s close connection to contemporary composers is again evident in the story of a first performance that the Hallé Choir gave in 1912. Unfortunately I completely missed this work in my earlier blog about the choir’s premiere performances, so I hope this will remedy the situation for any who might have spotted my omission! Granville Bantock is a composer little regarded today but at that time he was at the vanguard of contemporary British composition along with Elgar and, increasingly, Vaughan Williams. His choral symphony Atalanta in Calydon was a setting of a poem in the Greek classical style by the English poet Algernon Charles Swinburne who had died three years earlier in 1909 but who was in his time very much an acolyte of the Pre-Raphaelite set. Bantock wrote it specifically with the Hallé Choir in mind and indeed the score contains a dedication ‘to R.H. Wilson and the Members of the Hallé Choir, Manchester in grateful appreciation. However, Bantock made no concessions to the amateur nature of the choir. At times it is scored for four separate choirs such that there are up to 20 separate vocal parts at any one time. Gramophone magazine, in its review of a 1996 recording of the work by the BBC Singers, concedes that it is an ‘extraordinarily ambitious offering’.

This difficulty is reflected in the Guardian review of the work’s first performance on January 25th, 1912. In praising the trust Bantock put in Wilson and his choir in dedicating the work to them, he immediately puts in a large caveat: ‘But if he chose the choir as the most likely large body of chorus singers to place his work well before the public, it is nevertheless true that the work differed totally from everything that the choir had hitherto undertaken’. If this rings alarm bells, they are intensified by this description of the opening of the work: ‘The opening phrase of the men’s chorus was so much wanting in beauty of tone and the flexibility asked for by the composer that all hope of a fine interpretation of the opening section vanished on hearing it. To judge from this singing, the tenors and basses have trusted largely to the orchestra to give smoothness and grace to their singing’. However, the women of the chorus soon came sailing to the rescue: ‘In the third section of the symphony, for the women’s voices only, the singing was as good as in the first section it was poor, and it was only in this movement that the listener could receive a true impression of the music. It served to set the seal of success on the work’.

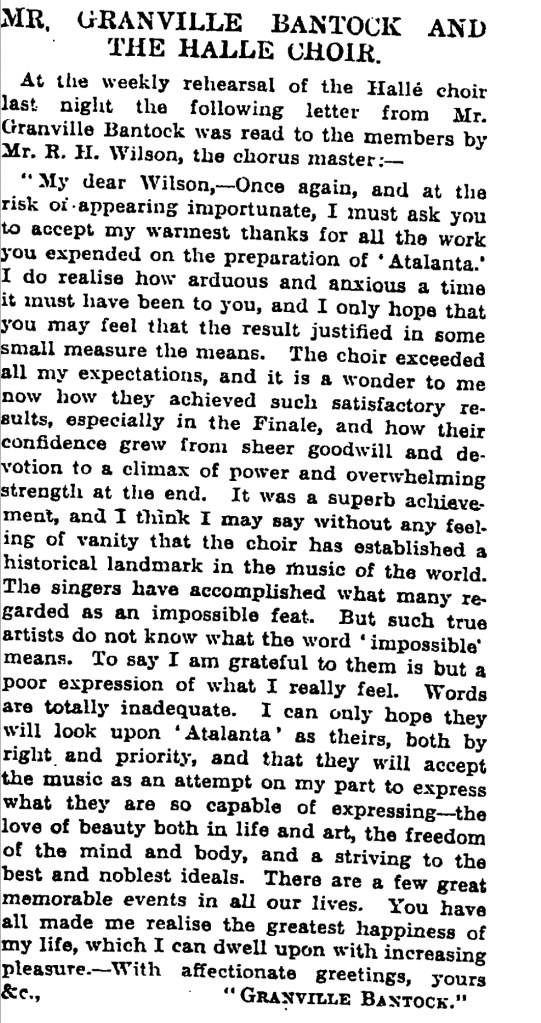

Overall, the reviewer felt that ‘the work may be considered as safely launched on the tide of public favour’, and this was reflected in the letter reproduced below that was sent by Bantock to Wilson and later published in full in the Guardian.

Sadly, though it received several more performances in the immediate aftermath of the premiere, Atalanta in Calydon has now, apart from that one isolated recording, vanished from the public gaze. Maybe Greek tragedy mattered little set against the very real tragedy that was put in train two short years later in 1914.

Michael Balling had succeeded Richter as chief conductor of the Hallé and the years leading up to the First World War appeared full of hope. The outbreak of war in 1914 ended all that. However, though R.H. Wilson took no fee for the duration of the conflict, the choir continued to perform through the war years. Moreover the association between Wilson and Elgar continued as the choir were involved in early performances of Elgar’s choral response to the war, finally recorded by the choir one hundred years later, conducted by Sir Mark Elder, namely The Spirit of England.

The Spirit of England was Elgar’s main response to the war during the conflict itself, a setting of three poems by Lawrence Binyon, one of which, For the Fallen, has remained familiar from countless Festivals of Remembrance over the years. This For the Fallen section was completed late in 1914 as reports of the first casualties began to filter back from France. The other two sections were finished in 1916 with the first performance of the complete work being given in Birmingham in October 1917. Despite occasional militaristic inflections, such as in Elgar’s depiction of the soldiers marching off to war, it is far from the patriotic jingoistic outpouring that one might have expected given the myth that had grown up around Elgar. In fact, much of it is imbued with a deep melancholy that make parts of it, especially the closing pages, feel like a true war requiem. As such it must have caused deep resonances in the minds of those early listeners given their knowledge of the sheer scale of the slaughter in the conflict.

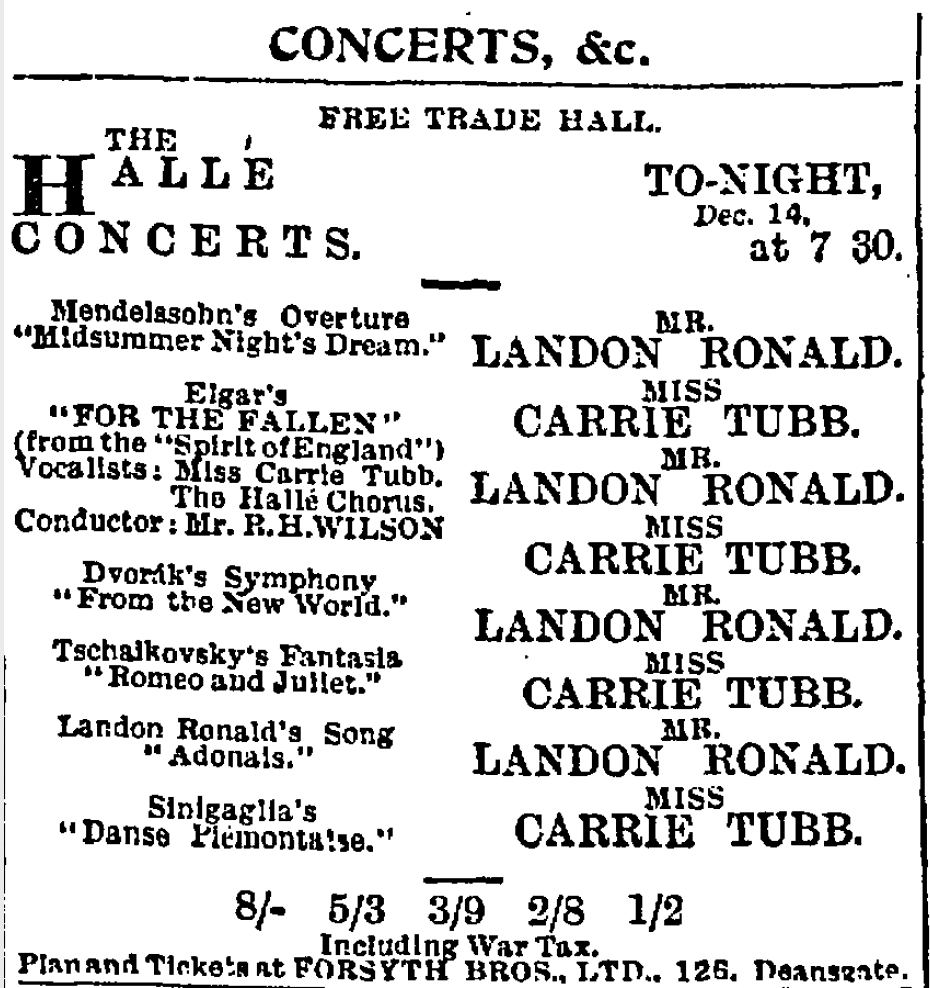

For the Fallen first appeared in a Hallé concert in December 1916, a short time after Elgar himself had conducted the Hallé Choir in a performance of The Dream of Gerontius. The performance was conducted by R.H. Wilson with Carrie Tubb as the soprano soloist. The Guardian reviewer made the connection between the ‘poignant expression of the sharpness of death to the single soul’ in Gerontius and ‘death when consecrated by the fellowship of our country’s cause’. As far as Wilson was concerned, despite his many years with the choir and his long association with Elgar, the review considered the performance ‘much the most creditable achievement that Mr. Wilson as chorusmaster-conductor has had’ – high praise indeed. Moreover, ‘in every instrument and voice one felt the conviction of what was due to the work, to its subject, and to the occasion’.

For the Fallen was reprised in March 1917 to a somewhat critical review in the Guardian, but in December of that year, two months after the Birmingham premiere, Wilson again conducted the choir in their first complete performance of The Spirit of England. The reality of a country in its fourth year of conflict affected the tone of the elegiac Guardian review, expressed as the outpourings of someone tired of war, though he also found time to underscore the close affinity between Wilson and his choir and Elgar:

The splendour of the long, sustained notes in the solos of the choral pieces lent a singular appropriateness to music which hymns a fortitude whose trial is still enduring, and the softness and vocal loveliness of other dying strains with which the solo closes were as appropriate in their pathos. To be in every sense satisfying now, during the fourth year of the war, these pieces are too purely, or at least too nearly, a philosophy of fortitude in defeat. We have fought too long in this strain to have any further delight in it, and have need for something more assured. The chorus has so much experience of Elgar’s music that its style has become almost instinctive to the singers even the allusiveness of the present pieces being everywhere given with relish and point.

Spirit of England Review from Manchester Guardian, 17th December, 1917

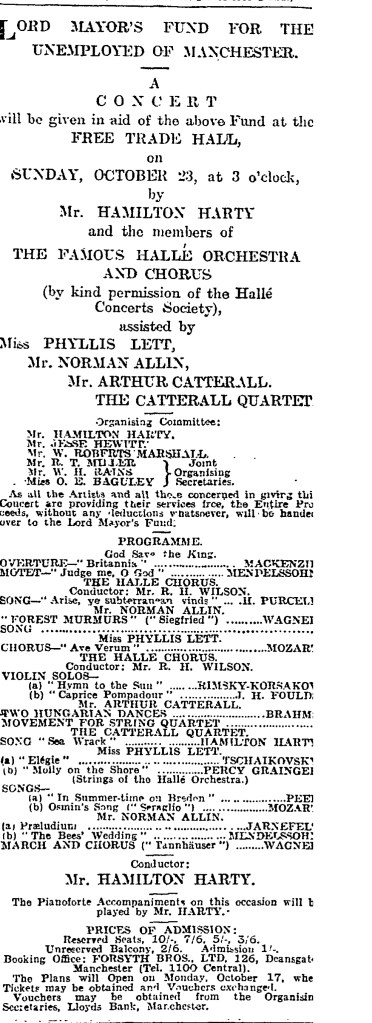

When the war ended in November of the following year Wilson was 60, but determined to stay at the helm of the choir he had served now for 28 years. As the promise of ‘Homes fit for Heroes’ following the war slowly dissipated so new problems arose and by 1921, just over 20 years after the Boer War benefit concert, Wilson was again involved in a large benefit concert, this time in aid of the ‘Lord Mayor’s Fund for the Unemployed of Manchester’, The bulk of this concert was conducted by Hamilton Harty who had been chief conductor of the Hallé in 1920 and would go on to rebuild its reputation during the course of the following decade. However, Wilson conducted the choir in two items, Mendelssohn’s setting of Psalm 43, Richte mich Gott, rendered here as Judge Me, O God and Mozart’s setting of Ave Verum Corpus, with Harty then conducting the choir in the final item, an extract from Wagner’s Tannhäuser.

There was comment within the Guardian review of the miscellaneous nature of the programme for the concert which ‘did not lean at all, as most charitable concerts appear to do, on its social object’. However, the reviewer felt that ‘the Hallé Chorus, conducted by Mr. R.H. Wilson, played a highly appropriate part in maintaining the more particularly sacred part of the programme’, praising the ‘soft legato singing’ in the Mendelssohn and the Mozart pieces. The fund benefited hugely, with Alderman Carter announcing during the interval that the proceeds from the concert had reached £500, over £24,000 in today’s money.

Following his earlier forays into musical commentary in 1904 with his lectures at the Whitworth Institute, Wilson continued to both speak and go into print on matters musical following the war. In 1922, in a lecture on ‘Hymns – good, bad, and indifferent’ at Central Hall in which he was assisted by members of the Hallé Choir singing examples, he outlined the history of English hymnody from Lutheran chorales through the influence of G.F. Watts and the Wesleys through to the present day. He railed against the ‘new school’ that had arisen that ‘despised this tradition and was bent on getting back to plainsong and Gregorian chants; in fact, to mediaeval melody’, and wished ‘to educate congregations and to eliminate the ornate and the sentimental’. He believed such a wish to be ‘gross impertinence’. Though only referred to as the ‘revised book’ in the report of this particular lecture, one assumes he was alluding to the recent published English Hymnal in which the editor Ralph Vaughan Williams had jettisoned many well known Victorian hymns in favour of hymns set both to folk tunes and from Tudor composers such as Tallis and Byrd. To Wilson ‘a good hymn should have style, outline, or contour of melody, should be contained within reasonable compass without ever going so high or so low that it forced some voices into silence, and it should fit absolutely its words’. He believed the best hymns to be those ‘that we could not imagine dissociated from their words’, and as an example got the choir to sing the hymn My God, how wonderful Thou art. As a contrast he got the choir to sing a hymn by Christina Rossetti from the ‘revised book’ which he described as ‘worse than the very worst Moody and Sankey’. The report does not name the hymn but we have to assume it is In the Bleak Midwinter for which Vaughan Williams had commissioned a tune from Gustav Holst for inclusion in the English Hymnal.

A further lecture the following year at All Saints’ Church, Manchester, which in the course of a general criticism of music-making in Church of England churches, also made it clear that the book he was aiming at above was indeed the English Hymnal, as this report shows:

Mr. Wilson referred to the young English school, and the advocates of plain-song who, he said, hoped by means of the English Hymnal to substitute for “your tunes”, ” The Churches one foundation” and “Jesus, the very thought of Thee,” tunes quite inappropriate to the times. The churches, he concluded, could yet become the musical centres of the country if they took up hearty congregational singing of hymns and of anthems.

From article in Manchester Guardian entitled ‘Bishop’s Advice on Church Music. Criticism by Hallé Chorus Master’, December 13th, 1923

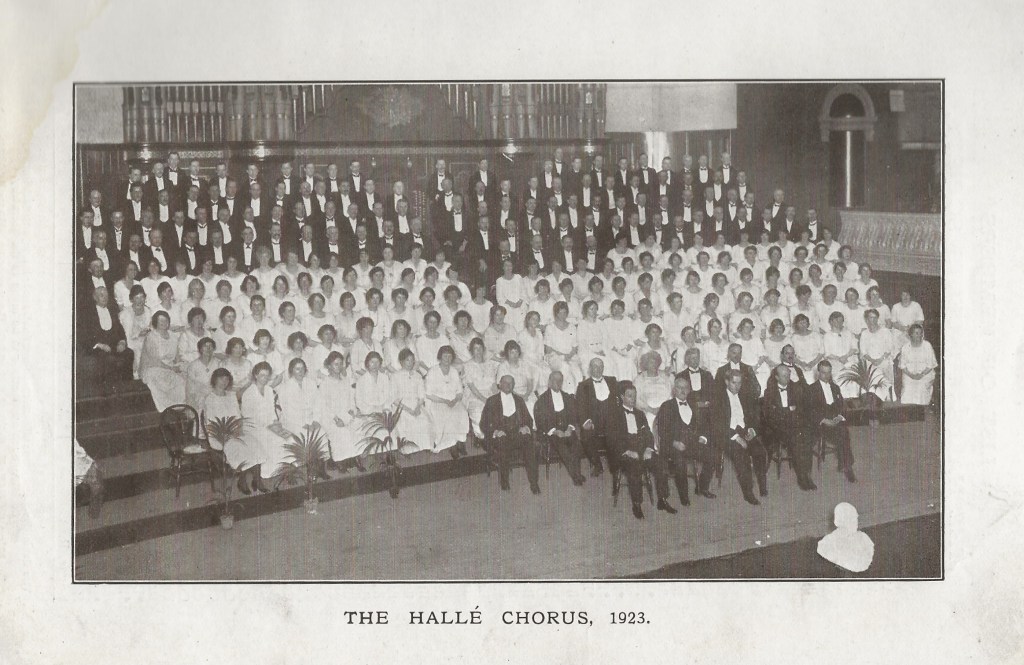

This report appeared a week before special performances of Messiah on the 20th and 21st December, 1923, the second of which was deemed to be the 100th performance of the work by the Hallé Orchestra and Choir (though more recent research suggests that number may have been reached earlier!). The souvenir programme for the concerts is notable for two things. Firstly, it contained a miniature version of the complete vocal score so that the audience could follow along with the singing, though presumably not join in! Secondly, it included a picture of Wilson with his beloved choir sitting in the choir seats in the Free Trade Hall. Wilson can be seen second from the left on the front row, next to the concerts’ conductor, Hamilton Harty.

Wilson was however nearing the end of his time with the Hallé Choir. The huge legacy that he would leave behind when he finally retired in 1925 was summed up in an article in the Guardian in April 1923 by their chief music critic Samuel Langford. Langford must have contributed many of the unsigned concert reviews I have quoted from above, so knew Wilson and his work with the choir intimately. He concludes the article thus:

Under Hans Richter and the present choir-master, Mr. R.H. Wilson, the Hallé Chorus perhaps reached its highest point of perfection, and for a few years not the public merely but the leading musicians of the city were loud in its praise. The war has made a difference for a time to that as to many another reputation. It is, however, a matter for the highest satisfaction that years of reconstruction under Mr. Wilson and the present conductor, Mr. Hamilton Harty, have not been unfruitful, and the performances of the Bach Mass [in B minor] especially have given a line of comparison with the past which is highly flattering to future prospects.

From article by Samuel Langford in Manchester Guardian entitled ‘Choralism in Modern Music – The Hallé Chorus’, April 21st, 1923

Wilson announced his resignation as chorus-master of the Hallé Choir at the beginning of 1925. He had served the choir for 36 years and his leaving was marked by a presentation from members of the choir on February 24th. The report of the presentation in the Guardian echoes the words of Langford above: ‘To know Mr. Wilson’s quality and appreciate his great services to the Hallé Society, the memory must be thrown back to the time of Dr. Richter’s musical reign in Manchester. Dr Richter’s ideas were sound and plain, and for the fulfilment of his requirements no more capable man could have been found in England than Mr. Wilson’. The respect that the choir had for its departing leader is made clear by the fact that the gift they presented to him was in fact a piano, inside which was a cheque that represented, in the words of the chairman of the choir committee, Mr. H. Pike, ‘an endowment fund to cover the cost of keeping the piano in tune’. In response, Wilson concluding a series of reminiscences of his time with the choir with the following exhortation: ‘Remember that the Hallé Choir has a long and brilliant history. Reflect on the great past, and see that there is no falling away from it’.

Robert Henry Wilson continued to involve himself in the choral life of the Manchester area. For example, the following year in 1926 he was active in trying to promote the idea of a civic choir for Salford. However, on January 20th, 1932 the Guardian broke the sad news of his death at the age of 75. He was survived by his wife Ada, who died nine years later in 1941. In his obituary, Neville Cardus outlined the extreme length and breadth of his work – his long service with the Hallé Choir, his time with the Birmingham Festival, his work with composers such as Elgar and Bantock and especially his relationship with Hans Richter. It praised his humour and how ‘he understood that it is easy enough to make English vocalists work hard if they are at once put in a good mood – and if their sporting instincts are aroused’. Cardus summed up Wilson’s worth with these final eloquent words: ‘He was a full man and a musician of a culture which in his day was unusually broad and humane. Manchester will not soon forget him’.

References:

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984)

Eleanor Roberts, The Hallé and the First World War, Actes du colloque international ‘Les institutions musicales à Paris

et à Manchester pendant la Première Guerre mondiale’ (Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris, 2021)

‘Our Special Correspondent’, ‘The Birmingham Musical Festival’, The Musical Times, 1906.

Elgar Society elgar.org

Guardian Archive

Hallé Archive

myheritage.com

University of Manchester Minerva service

Leave a comment