Much of what I’ve written about so far in this blog has been concerned with the Hallé Choir as an overall entity, with its birth and development, and with the growth in its repertoire and the reactions of the critics and the general public to its performances of that repertoire. However, it should never be forgotten that through the years the choir has been made up of thousands of ordinary individuals who have selflessly given up their time week after week for the greater good of the choir. In the best sense of the word they are true amateurs who often at considerable expense both in terms of time and money have devoted themselves to achieving the finest professional choral standards in support of Charles Hallé’s excellent orchestra.

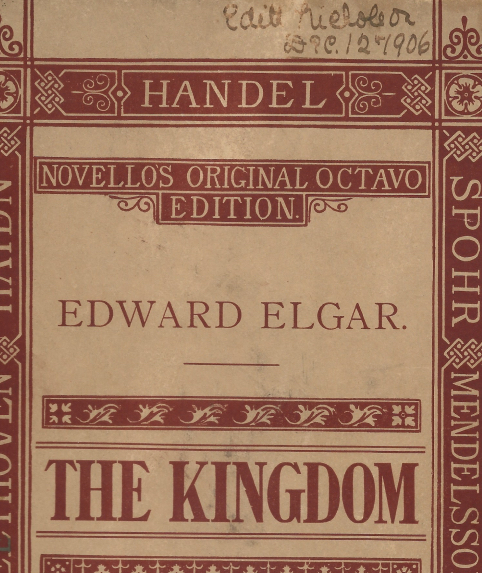

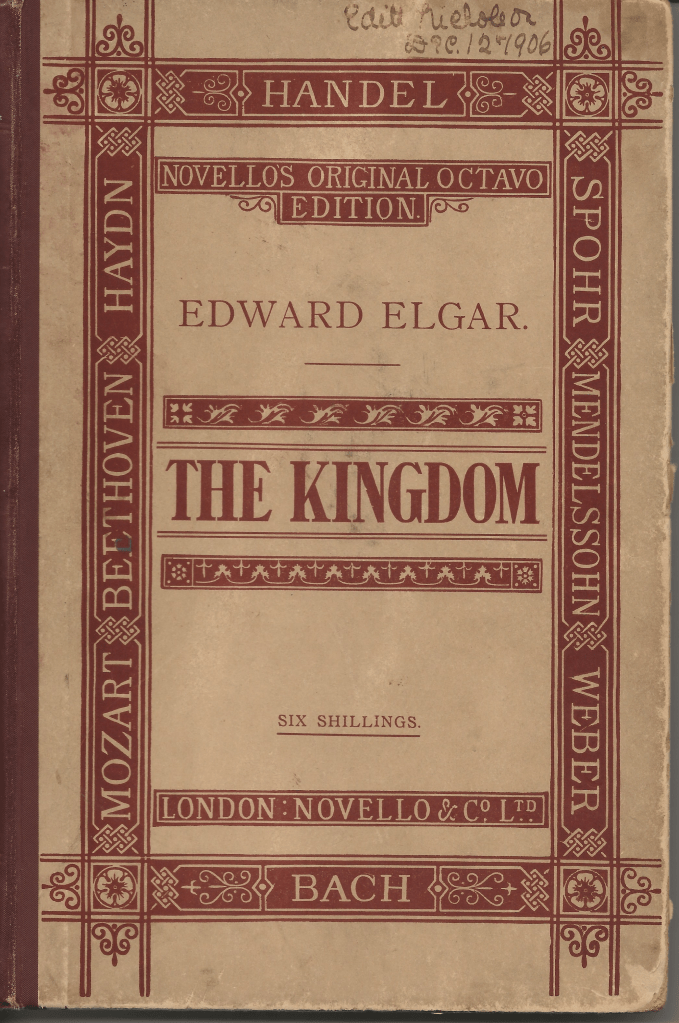

A lucky chance has provided me with the opportunity to highlight just one of these ordinary individuals, whilst at the same time, in preparation for the Hallé’s celebration of the oratorios of Edward Elgar in June 2023, providing some background as to how the works of Elgar entered the choir’s bloodstream in the first decade of the 20th century. That chance was provided me by one of my fellow basses in the Hallé Choir, Vin Allerton, who had come into possession of two early Elgar vocal scores. One was for The Apostles, with indications within that it was purchased for performances of the work by the Hallé Choir in the 1920s. The other was far more interesting – a first edition of the vocal score for The Kingdom that was evidently purchased for the very first Manchester performance of the oratorio by the Hallé in early 1907.

Using the Hallé archives, census records and other historical material I’ll tell the story of Edith Nicholson, contralto, who bought that score for six shillings in December 1906 and was there on February 14th, 1907 to help present The Kingdom to the Manchester public for the first time. As you will see she appears to have led an unremarkable life, as have so many of we choir members through the years, but one in which for brief moments she was part of something truly remarkable, the raising of massed voices in the singing of remarkable music by remarkable composers.

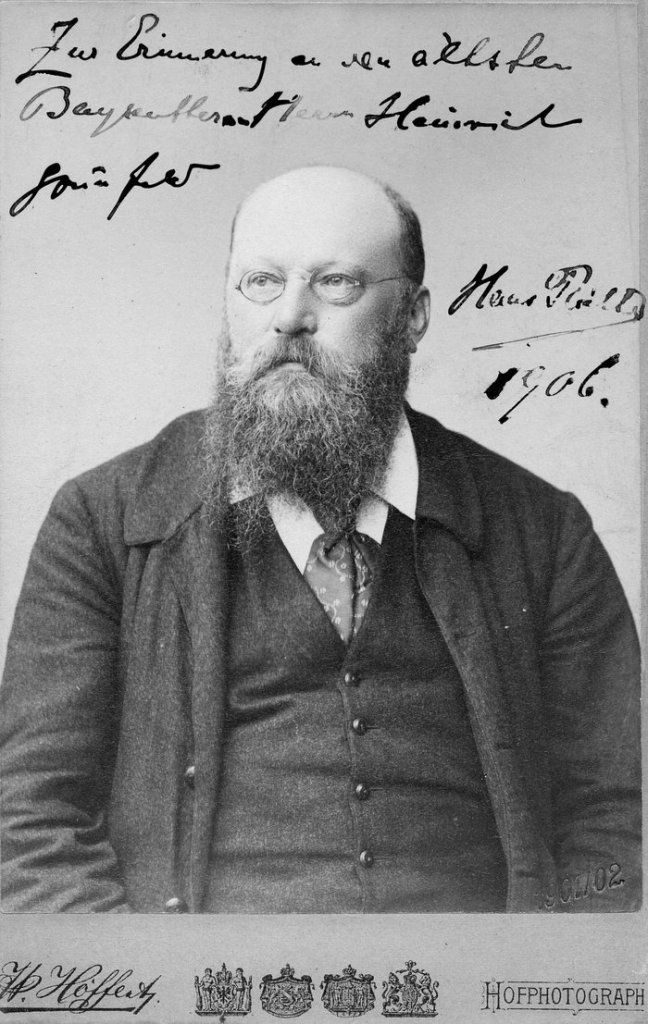

To begin though, I’ll say a bit about how very early on in their life the Hallé Choir first gained a reputation for their performances of the great Elgar oratorios, a reputation that has been enhanced in recent decades under the baton of Sir Mark Elder, but which began with his illustrious predecessor, Hans Richter.

The Austro-Hungarian conductor, Hans Richter, had made a name for himself in the latter half of the 19th century as a Wagner specialist, and also as a champion of the late Romantic repertoire, for example conducting the premiere of Brahms second symphony with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1877. From 1879 onwards he had made frequent appearances in England, and indeed on the very day that Charles Hallé died in October 1895 he was conducting in Manchester.

During the last years of his life Charles Hallé had been in discussions with textile magnate Gustav Behrens to insure the continuance of his concerts after his death. Following his demise Behrens, along with Henry Simon and James Forsyth, took over financial responsibility for the concerts. The hardest decision they had to address was who to appoint to succeed Hallé as chief conductor of his erstwhile orchestra. A series of temporary appointments were made, especially Frederic Cowen, who took over the reins from 1896 to 1899, but in 1899, following the formal incorporation of the society, a more permanent successor was appointed, one whom many considered the best conductor in the world, namely Hans Richter.

1899 was also the year that Richter conducted the first performance of the work that finally made the name of the foremost exponent of late English romanticism. Edward Elgar. That work was Enigma Variations, first performed in St James’ Hall, London in June 1899. Elgar was by this time already 42 and had struggled to gain acceptance from the musical establishment for a variety of reasons, specifically his lowly background as the son of a Worcester piano tuner, his lack of a formal musical education and his Roman Catholicism. A number of works had caused a degree of interest, his early salon pieces like Salut d’Amour, his Serenade for Strings of 1892 and oratorios such as King Olaf and Caractacus, but Enigma Variations became his calling card to the wider world.

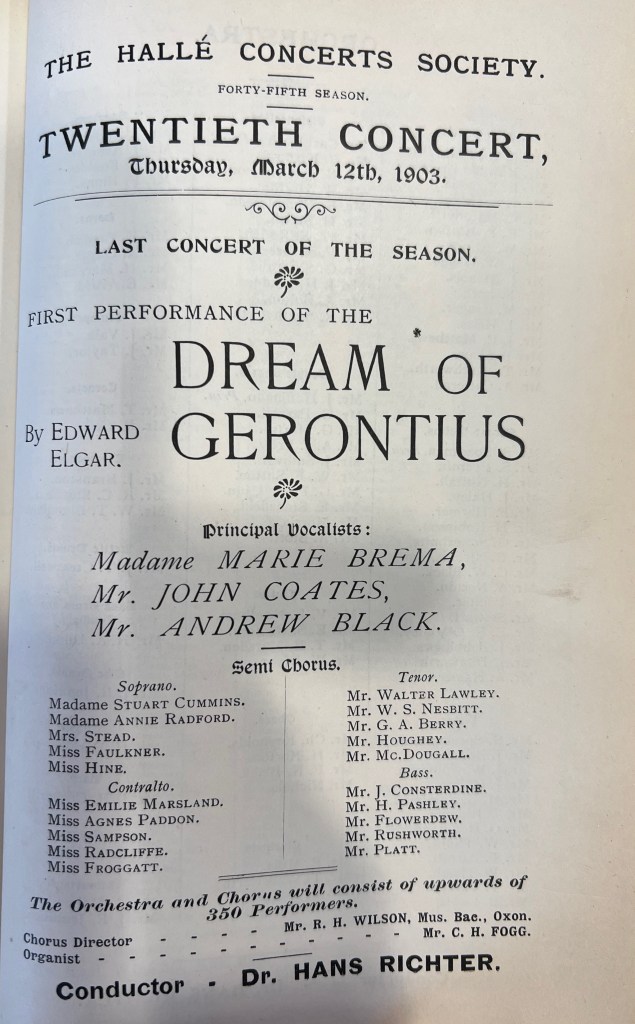

A year later in 1900 there was confidence that his reputation would be bolstered further when the the Birmingham Festival commissioned him to write a choral work based on John Henry Newman’s poem of a soul’s journey from life to the afterlife, The Dream of Gerontius. To further add to the expectation they engaged Richter to conduct the first performance.

However, for a variety of reasons well documented by Jerrold Northrop Moore in his biography of Elgar, the run up to the first performance of on October 3rd 1900 was fraught. Delays in producing the finished score meant that the chorus only had time for seven rehearsals and Richter himself only received the full orchestral score ten days before the concert. Things came to a head in the one and only, public, orchestral rehearsal when after the choral singing fell apart in the notorious Demon’s Chorus, Elgar leapt to his feet to stop the rehearsal in order to castigate the chorus.

The actual performance itself was little better. The review from the Manchester Guardian was generous, proclaiming that ‘the only defect was the occasional flat singing of the chorus’, but Elgar found the experience a deflating and depressing one, writing to tell his friend and editor August Jaeger that ‘I have allowed my heart to open once – it is now shut against every religious feeling & every soft, gentle impulse for ever.’

The work would not be performed again in England for nearly three years. In the meantime, a German translation of the text by the conductor Julius Buths and a number of successful performances of this version in Germany including one after which Richard Strauss proclaimed Elgar to be ‘the first English progressive musician’, meant that by 1903 the work was ripe for rehabilitation in its homeland.

The first London performance of Gerontius, conducted by the composer, took place in the apt setting of Westminster Cathedral in June 1903, but three months earlier, on March 12th, the Hallé and the Hallé Choir gave what quickly came to be regarded as, at that point, the definitive performance of the oratorio. This first Manchester performance, despite having to be delayed by a week because of illness amongst the soloists, was a triumph. The conductor was, as at the premiere, Hans Richter, but this time there were no problems with regard to rehearsal time and the performance. Richter and the chorus master R.H. Wilson had obviously decided the performance would not fail for lack of preparation, as the Guardian correspondent understood in his review, with its implicit allusion to the Birmingham premiere at the start of this extract:

Dr. Richter was, for various reasons, peculiarly anxious that it should go well; Mr. Wilson made up his mind some time ago that whatever conscientious work could do to secure a worthy performance should be done; the hopes and endeavours of choirmaster and conductor were seconded by the choir in an admirable spirit, and, though it seems that for some time the usual difficulties of an unfamiliar style were felt, not a trace of any such thing was to be observed in the performance, the remarkably willing and energetic style in which the choral singers had grappled with their task bearing its proper fruit in a rendering that sounded spontaneous and unembarrassed, as though the singers were sure of the notes and could give nearly all their attention to phrasing, expression, and dynamic adjustments.

Manchester Guardian review – March 13th, 1903

The reviewer gave special praise to the semi-chorus and the way they blended with, but remained distinguishable from, the main chorus, concluding his review by describing ‘the strong impression created by the whole performance’: ‘…the audience… remained applauding for a considerable time at the end, till conductor and principals had bowed their acknowledgments repeatedly, and there were other indications of unwonted excitement and enthusiasm.’

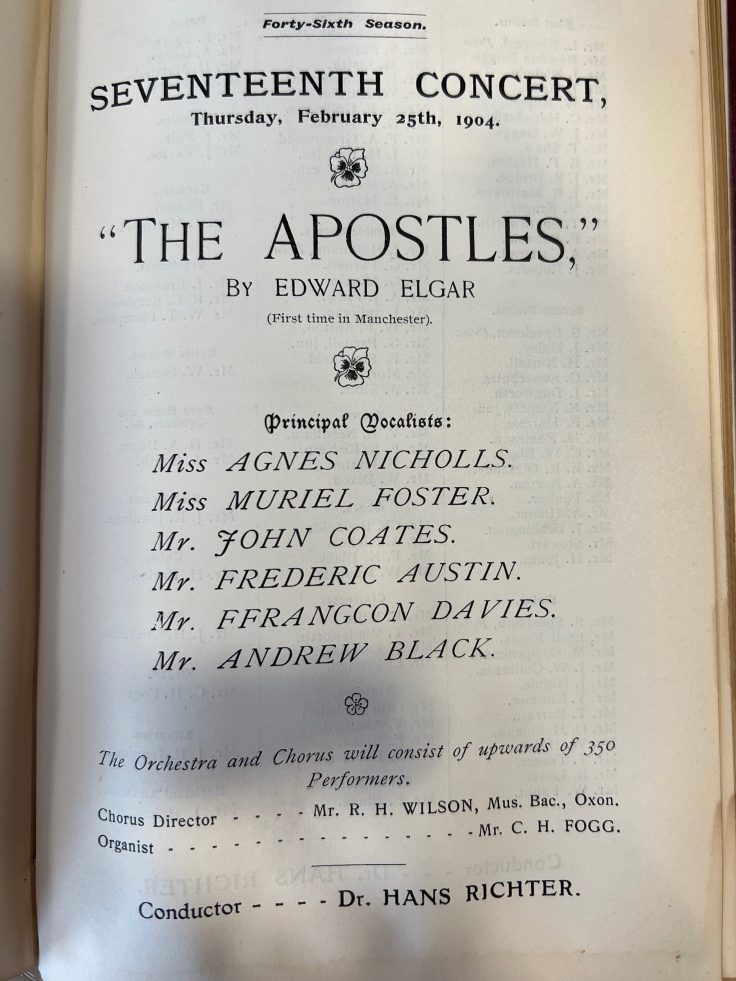

October 1903 saw the first performance, again at the Birmingham Festival, of what was designed by Elgar to be first in a sequence of three connected oratorios, The Apostles. This was essentially a retelling of the story of Christ’s crucifixion, an English Passion if you will, and was followed shortly after by The Kingdom, a retelling of the events of the Acts of the Apostles. Following a crisis of faith, the third oratorio, intended to be based on the Last Judgement, was never written.

The first Manchester performance of The Apostles followed closely on from the Birmingham premiere, with Richter again conducting an orchestra and chorus of ‘upwards of 350 performers’ on February 25th, 1904.

The response, at least according to the reviewer in the Manchester Guardian, was more muted than for Gerontius the previous year, but there was general praise. Considering the work to be, in terms of technical difficulty, a ‘[Berlioz] “Symphonie Fantastique” and [Beethoven] Mass in D combined’, the reviewer was not expecting ‘faultless rendering’. However, he did regard the performance ‘highly satisfactory’, with ‘the general intonation of the choir… better than on any previous occasion, all the delicate fluting rapture of the celestial choruses at the end sounding wonderfully sweet and showing not the least traces of fatigue.’ The orchestral playing was, he felt, ‘more subtle than at Birmingham… a better justification of the composer’s extraordinary colour schemes.’

However, at the end of the night the reviewer felt the performance did not achieve quite the same level of public acclaim as Gerontius had done: ‘There was applause, of course, yesterday, but no scene of great enthusiasm such as the earlier and simpler oratorio evoked.’

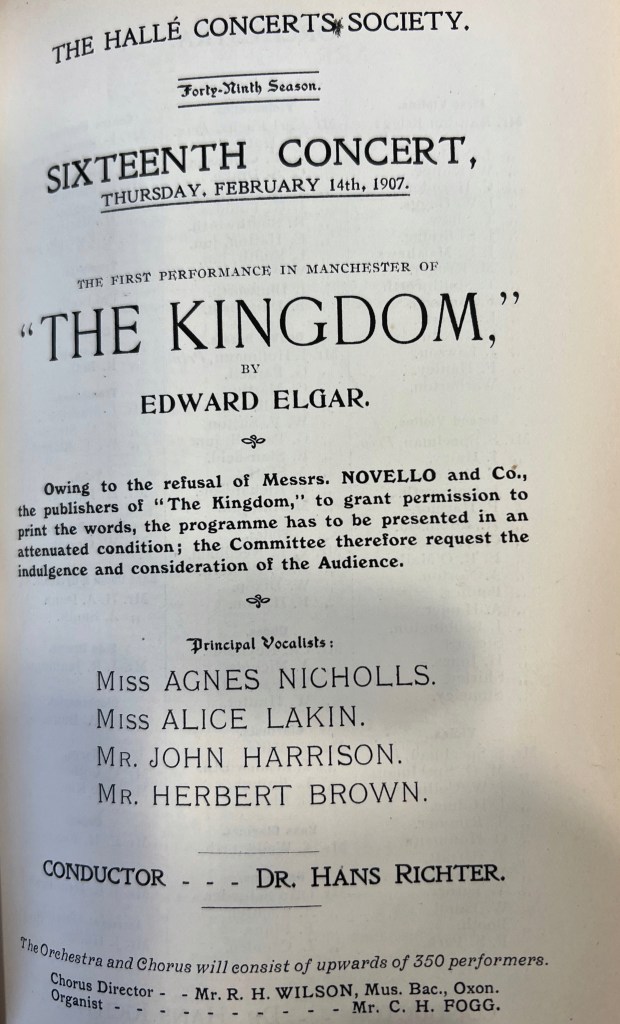

Elgar completed the second part of his proposed trilogy, The Kingdom, for the next instalment of the triennial Birmingham Festival in 1906 and he conducted the first performance himself in Birmingham Town Hall on October 3rd of that year. The first Hallé performance, again conducted by Richter, followed shortly after in February 1907, which brings us, as promised, to one of the members of the Hallé Choir who sang in that performance, Edith Nicholson.

We see her listed in the programme simply as Miss Nicholson, and she had also sung in the performance of The Apostles in 1904. But who was ‘Miss Nicholson’? How can we uncover the background of this ordinary member of an extraordinary choir? Luckily, she wrote her given name, Edith, and her address into her copy of The Kingdom which makes it much easier to trace her life before and after her membership of the Hallé Choir and bring alive the real life of this otherwise anonymous member of the chorus.

Thus we find that Edith’s father Alfred was born in Manchester in 1849, though as his older brother Robert was born in Maidstone, Kent in 1842 one assumes that like so many families in the first half of the 19th century the Nicholsons had moved north in search of betterment. In Alfred’s case he eventually found a career within the cotton industry that had made Manchester preeminent in the world.

In the summer of 1875 Alfred married Jane Elizabeth Ward, born in the same year as Alfred in Liverpool. Jane Annie Edith Nicholson, who proved to be their only surviving child, was born two years later in 1877. This plethora of first names mean that this daughter is slightly difficult to track down in the records as at various times she was known by different combinations of the three names. Indeed, the Birth Index for 1877 shows her as ‘Jane Edith A.’. However, as it appears the name she knew herself as was Edith, we shall call her that for the rest of this history.

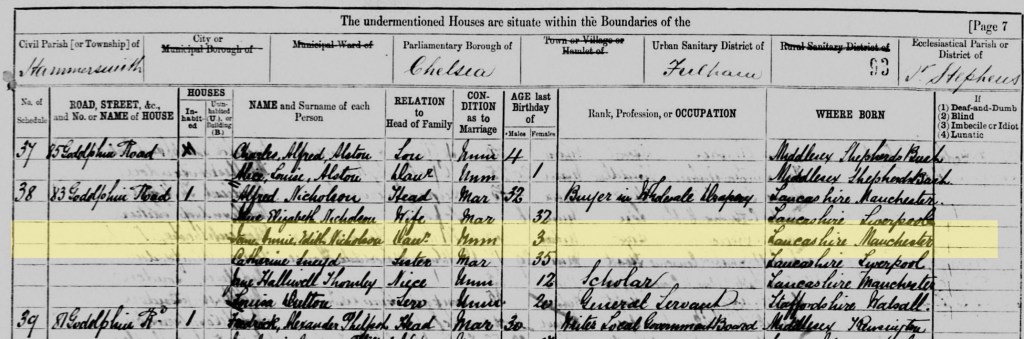

The Birth Index shows Edith as being born in Chorlton, but the census return for 1881, the first in which Edith appears, shows that by this time the family had migrated down south. Alfred is shown as living at 83 Godolphin Road, Hammersmith. As can be seen from the photograph below, this was a modest middle-class dwelling, but it was large enough to house Alfred’s wife Jane, Edith, Alfred’s married sister, a niece, and as an indication of his status, a servant. He is shown as being a ‘Buyer in Wholesale Drapery’ a profession he continued following under various descriptions through his life.

One thing that the Nicholsons didn’t seem to ever do was to stay in one place for too long and by 1891 Alfred and Jane had relocated back north to 247 Upper Brook St, Chorlton-on-Medlock, on what is now the A34 opposite the present-day Manchester Royal Infirmary. Alfred and Jane are shown in the census as living with Jane’s sister, two nieces, a nephew, and a servant. Alfred is now described as a ‘Warehouseman’.

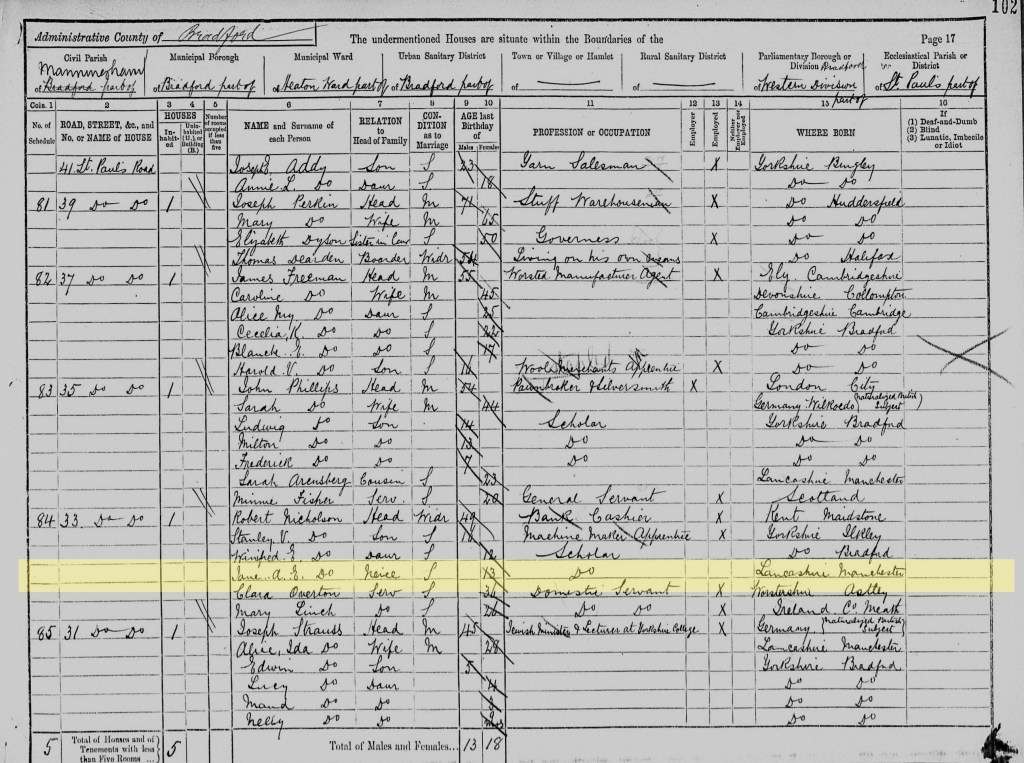

However, Edith was not present for the census. Now 13 she had obviously been sent away for her education and is shown living with her uncle Robert at 33 St Paul’s Road, Manningham, Bradford where ‘Jane A.E. Nicholson’ is listed as a ‘scholar’ alongside her cousin Winifred. At the time Manningham was an immensely important industrial suburb of Bradford and home to a large German community, as is shown by the fact that Edith’s next-door neighbour was Joseph Strauss, a German Jewish minister and lecturer at a local college. Many of the streets in Manningham are named after German cities – indeed, three years later in 1894 the novelist J.B. Priestley was born in nearby Mannheim Road. One other German immigrant to Bradford around this time was Julius Delius whose son Fritz achieved fame as a composer after changing his name to Frederick Delius, writing many works that have been performed by the Hallé Choir over the years.

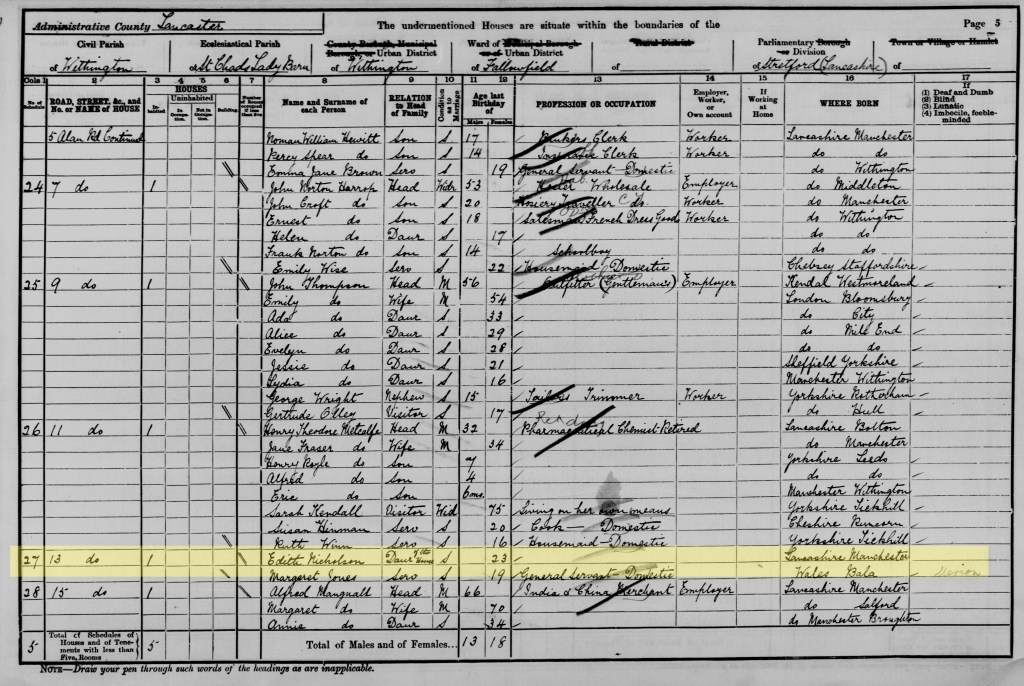

Sadness struck Edith’s little family in early 1898 when her mother died, and one can imagine Edith, now in her early 20s, deciding to stay home and look after her father. Thus, in 1901, listed just as ‘Edith’, she is shown as living at 13 Alan Road, Withington (yet another move!) and is described as ‘Daughter of the House’. One servant is listed as making up the household on the census day, as Alfred was away from home and was listed a ‘visitor’ at a lodging house in Blackpool, described as a ‘Buyer in Cotton Goods’, though he was surely permanently living in Withington with his daughter. Though she was 23, Edith is not shown in the census return as having an occupation, and indeed there is no record in any census return of her having a job other than ‘unpaid domestic duties’. Her lot in life, as with so many at the time, appeared to be looking after the house for the men in her life. Maybe it was around this time that she decided to provide herself with a bit of outside interest by joining a choir – one can only speculate.

Sometime between 1901 and 1906 Alfred and Edith moved to what appears to have been a newly built house, 2 Blair Road, Alexandra Park. Interestingly this is a very short distance from William Hulme’s Grammar School where the Hallé Choir rehearsed frequently in the early 2000s and it must have been around this period in her life that Edith joined the Hallé Choir.

So it was that on December 12th, 1906, Edith inscribed her name and address in a new copy of the vocal score for Elgar’s The Kingdom. Maybe she bought her copy from Forsyth’s music shop in Deansgate, relatively new premises following their move from St Ann Street in the 1890s, or maybe her copy was bought for her by the choir. However she obtained her copy, she soon personalised her copy by writing her name on the front cover and her address on the page of the score where Elgar habitually inscribed the letters A.M.D.G, short for ‘Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam’ or ‘To the greater glory of God’, the motto of the Jesuits.

Her participation in the first Manchester performance of the oratorio was memorialised within the score by Edith through her inscription on the title page of the score – ‘First produced in Manchester, February 14th 1907. Agnes Nicholls, Alice Lakin, Harold Wilde, Herbert Browne.’ The latter were the soloists at that first performance though she gave Herbert Brown an extra ‘e’!

From the score it was obvious that Edith was a First Alto, though other than putting an asterisk against her line throughout the score there are remarkably few markings within the score compared to the number a modern chorister would put in – just a couple of breath marks and little more. What is interesting is the list of sits and stands. Provided by the chorus master R.H. Wilson, they had obviously been formally sent to a printer to be produced professionally. Edith placed this printed list within the score but didn’t write them into the actual score. The numbers shown on the list refer to rehearsal numbers rather than page numbers. There was obviously no concept in Wilson’s mind of sitting or standing on a particular beat of a particular bar as is normally the case with present-day choirs.

What therefore of this first Manchester performance of The Kingdom in which Edith appeared? The Manchester Guardian correspondents lays on the praise from his very first paragraph which I will quote in full as I can imagine Edith reading it with pride:

The warmest and most unreserved congratulations are due to the Hallé Concerts Society on their production of Elgar’s last oratorio. If it was indeed noticeable that the work was being given for the first time, it was only in the best of all possible ways – by the freshness and sincerity of the whole performance. Even for the merit of the performance the first thanks are due to the composer, who in this work shows that, in whatever direction he may be moving aesthetically, he is a least still making great strides forward as a “practical” composer. Almost every idea comes out well. The second person to congratulate is the conductor, for the balance of the whole work. He has shown what he can do if only he is allowed a full rehearsal with chorus and orchestra. All that can possibly be suggested as improving the performance is that a still more daring pianissimo from the players when the voices are singing softly might – it is not safe to say would – have produced a still finer effect. It is possible that the chorus master thought himself robbed of some of his laurels. Even as it is, Mr. Wilson may justly be very proud of the work of the choir. From the first note to the last the singers showed that they were intent not on the notes principally but on the expression. And in this respect they were always trying for the right thing. There was an entire absence of the rough, mistaken staccato effects we have had at so many other concerts. The choir was prepared, even more than orchestra or soloists, for the mystic sudden pianos. And they showed that by singing Elgar’s music they have learnt something of the difficult art of working up steadily through long climaxes. In a few passages the sopranos failed to give quite the full pitch to the highest and most trying notes – and how bitterly they have to pay for the slightest shortcomings in this respect! – but the steadiness of the other parts prevented anything more than the most transitory ill-results. It is indeed refreshing to hear a concert where the chorus singers do not accept a lower standard of expression than the solo singers.

Manchester Guardian review – February 15th, 1907

I wonder if Alfred was in the audience that night at the Free Trade Hall? I can imagine them walking home together to Alexandra Park or riding back on the top deck of a tram, he praising his talented daughter and she telling him tales of that strange Dr Richter, and what a wonderful experience it was despite the sopranos missing those top Gs… again!

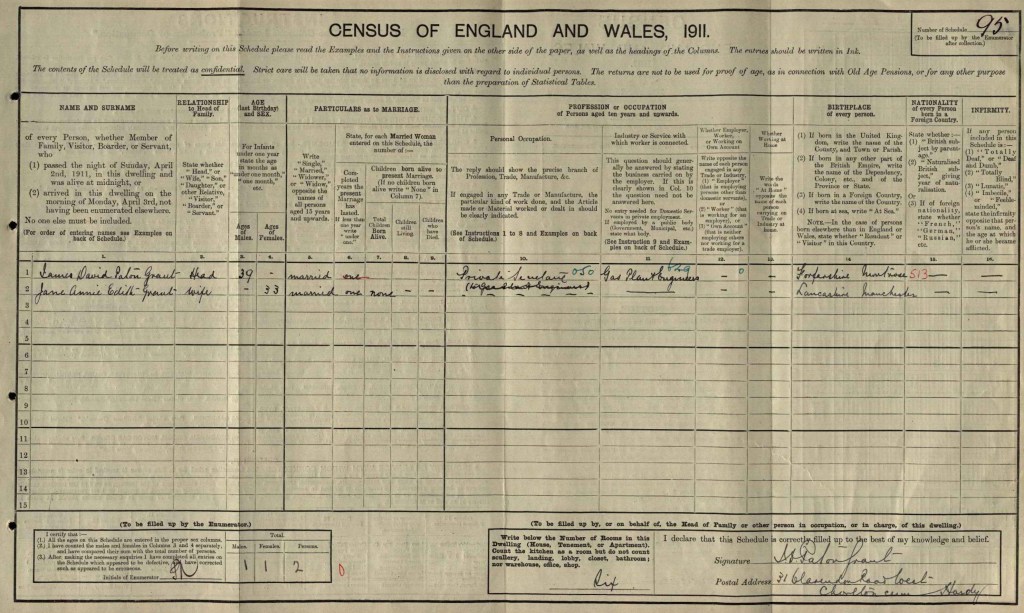

What happened to Edith in the years that followed? Her life with Alfred didn’t last much longer as in the census of 1911 Alfred is still living at 2 Blair Road, not with Edith but with his new wife, having married 42-year-old Sarah Gertrude Jamison the year before. One imagines that Edith, now in her late 20s, may have seen the kindling of a relationship between Alfred and Sarah as an opportunity to seek out love for herself, as the prospect of a lifetime looking after her father began to recede. She therefore actually beat her father to marriage, marrying James David Paton Grant in 1909. James was a Gas Plant Engineer from Montrose 6 years her senior and by 1911 they were living at 31 Clarendon Road West, Chorlton-cum-Hardy.

Sadly, they do not appear to have had any children, and by 1921 James had had a career change and was working as Secretary at Tilstone House near Tarporley in Cheshire, a large mansion built by Lord Daresbury as a hunting lodge. Tilstone House is maybe now more famous for the fact that much of it was gutted in a fire in 2020 that many later suspected was arson. James commuted to work from the couple’s new home, Chilford, Keele Road, Newcastle-under-Lyme.

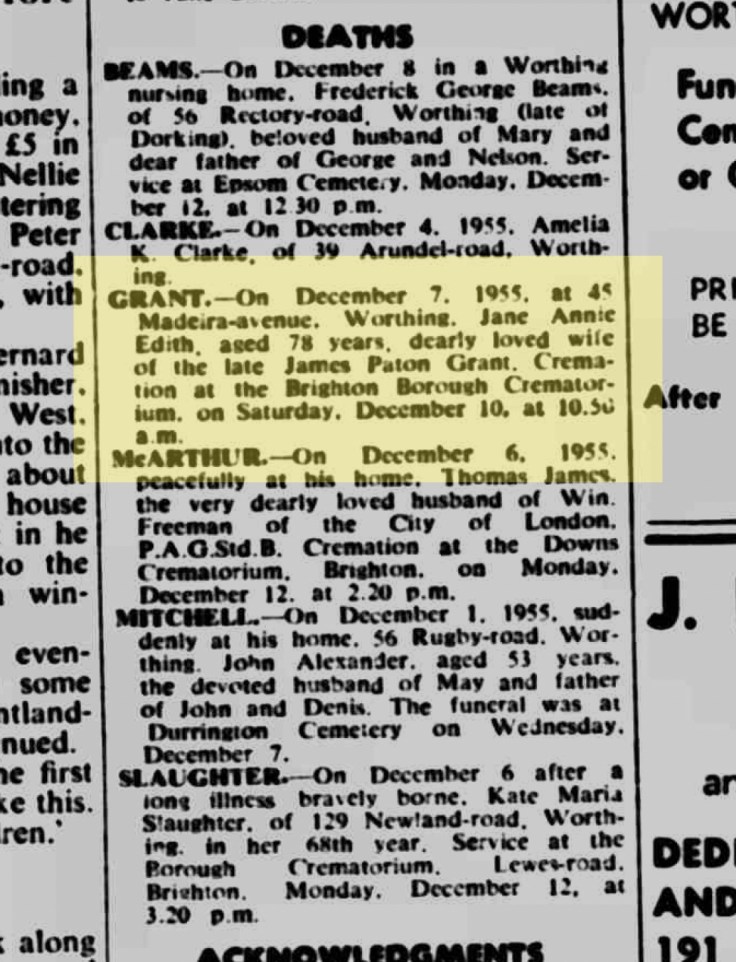

Yet another move came before the outbreak of war in 1939 by which time the couple are shown as living in Thoresby Road, Wilmslow, presumably in happy retirement as James was by now 67. They lived here throughout the war but sadly James died soon after in 1946. As an only child and with no other dependents, Edith was obviously quite comfortably off so took the decision to move to the south coast where she purchased a modestly grand detached house on Madeira Avenue in Worthing, Sussex. It was here that she died on December 7th, 1955, aged 78. Jane Annie Edith Grant’s death notice in the Worthing Herald describes her just as the ‘dearly loved wife of the late James Paton Grant’, with no mention of her time singing with the Hallé Choir nearly 50 years before.

The relationship between the Hallé Choir and the choral music of Edward Elgar that began with Hans Richter in the first decade of the 20th century has remained strong down the years. There was a classic recording of The Dream of Gerontius made by John Barbirolli, in which the choir were joined by Janet Baker, Kim Borg, Richard Lewis and the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus, that many consider the definitive recording of the piece. Others however may point to the recording Sir Mark Elder made with the choir in 2008 that together the recording he made of The Kingdom in 2009 and of The Apostles in 2012 made up a trio of award-winning recordings. This legacy will be picked up again in June 2023 when over the course of two weekends the Hallé Choir will sing all three of these great oratorios.

Edith Nicholson by contrast is now forgotten (though if anyone reading this has more information about her I would love to hear from you). However, her place in the long line of ordinary people who have sung in the Hallé Choir since its beginnings in 1858 is assured, and in that sense she will never be forgotten, especially as she was there when, as far as Elgar is concerned, it all began.

References:

Edward Elgar, The Kingdom. An Oratorio. – Op. 51. [Vocal Score.] (London: Novello and Co, 1906)

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

Jerrold Northrop Moore, Edward Elgar : A Creative Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984)

‘Our Manchester Correspondent’, ‘Seventy Years of the Hallé Orchestra’, The Musical Times, 1927.

Guardian Archive

British Newspaper Archive

Hallé Archive

myheritage.com

freebmd.org.uk

Google Street

Leave a reply to Hallé Choir Knights Part 1: Sullivan, Stanford, Elgar and Wood – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply