To celebrate this year’s performance of Handel’s Messiah on December 10th I thought I would write a blog to show how the look and sound of Messiah, as performed by the Hallé Choir, has changed over the years since the first performance of this great work on Ash Wednesday, 1859. By looking at a few particular performances of Messiah over the years, I’ll also be able to take a look at some of the notable singers who have sung with the choir on such occasions and also at the varied locations in which the choir has performed Messiah.

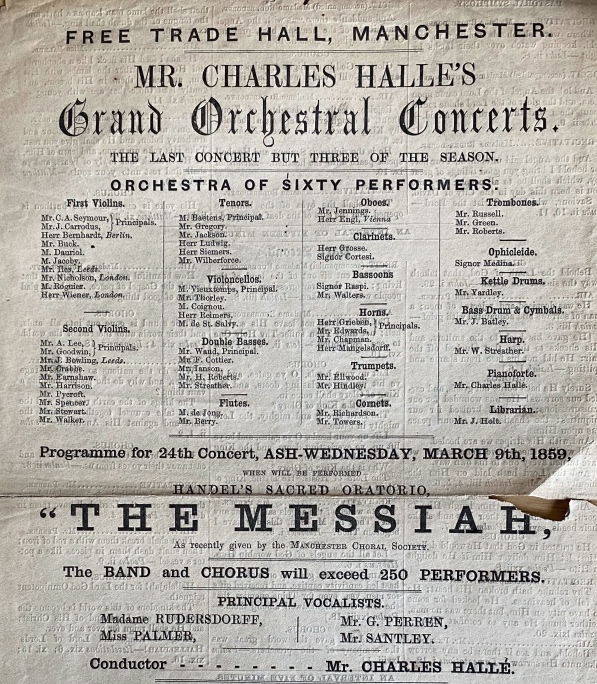

March 9th, 1859

In Part 1 of my first blog, ‘Mr Hallé’s Choir’, I wrote about the development of the choral tradition in Britain and the crucial part Handel’s Messiah played in the development of that tradition. In particular I wrote about how from small beginnings, where the work would be performed by a small Baroque orchestra and small choir, a tradition grew, especially through the 19th century, of putting on much larger scale performances of Messiah with huge orchestras and massed ranks of choral singers – Messiah as spectacle, if you will. This was helped in no small measure by a number of composers ‘improving’ on Handel by re-orchestrating Messiah to suit the orchestral forces available to them, taking the wind forces, for example, way beyond the bassoons, oboes and trumpets that Handel wrote for.

Chief amongst these orchestrations was that produced by Mozart for a German language performance of Messiah in Vienna in 1789, an arrangement that was later published in 1803. Whilst Mozart preserved Handel’s vocal and string lines, he added flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, horn, trombone, trumpet, and timpani parts and rewrote the trumpet parts to suit the changing technique of the time. This beefed up arrangement, especially when transcribed back to the English language original, formed the basis of most of the further versions of the oratorio that appeared through the 19th century, culminating in the famous Ebenezer Prout edition of 1902.

I talked at length about the first performance of Messiah following the inauguration of Charles Hallé’s Grand Orchestral Concerts in 1858 in Part 2 of my first blog. Whilst the front page of the programme does not explicitly state which arrangement was used, you can tell from the list of orchestral players in the programme that the instrumentation reflects the orchestral arrangements that Mozart pioneered. In addition you can see that when Charles Hallé himself played the keyboard continuo whilst conducting, a tradition continued by many current conductors of Hallé Choir Messiahs, he played it on the piano!

Note also the date of the concert – Ash Wednesday, March 9th 1859. It is largely forgotten now that Messiah was conceived as a Lenten and Easter piece, and first performed as such in 1741. Whilst the first part of the oratorio includes a section on the Birth of Christ, its main themes revolved around Christ’s Passion and Resurrection, and the life to come. It was therefore initially far more likely to be performed in the run-up to Easter than in the run-up to Christmas, and that is the case here.

December 22nd and 23rd, 1887

Less than thirty years later, as we can see from the programme for the performance of Messiah in 1887, the work had become firmly established as a Christmas piece, rather than as an Easter piece, the two performances here taking place just before Christmas.

Still under the baton of Charles Hallé, the orchestra had grown even from the large orchestra (for Handel) of 1859, and now numbered 100 players. Meanwhile, the choir, now under the temporary direction of Herr Beyschlag following the sad demise of Edward Hecht earlier in the year, numbered 250. The sound filling the Free Trade Hall must have been remarkable, and we have confirmation from the programme that that sound was most definitely derived from Mozart – ‘with additional Accompaniments by Mozart’. We can also see how popular an event Messiah was becoming in the Hallé concert calendar – these were now the 40th and 41st performances of Messiah in only the 30th season of the orchestra. The tradition of two annual performances of Messiah, which can still be seen today with choirs such as Huddersfield Choral Society, continued for some time to come.

December 19th, 1912

This was not the case in 1912, however. This special announcement in a prior concert programme reminded potential audience members that because there was to be only one performance of Messiah that year, tickets would be at a premium. What is especially interesting about this announcement is the short window of opportunity the public had to purchase tickets, with ticket applications for a concert on December 19th only being processed by the ticket agents on December 9th. What is also interesting is how ticket prices have largely kept in line with inflation. The cheapest tickets were 1 shilling, which would be around £7 today, and the dearest 7 shillings and sixpence, around £50 today.

The concert was conducted by the German conductor Michael Balling, who had succeeded Hans Richter as principal conductor of the orchestra earlier that year, continuing the German tradition that had been established by Charles Hallé and had only been interrupted thus far by the English composer/conductor Frederic Cowen. The numbers involved were still massive – ‘upwards of 350 performers’ – and very Mozartian. As can be seen from the orchestra list below, it even included a Mr H.A. Dunn playing the glockenspiel!

However, in the following passage from the programme notes for the concert there was at least some indication of some idea of ‘authenticity’ when it came to performances of Messiah:

Originally written only for strings, trumpets, oboes, bassoons, organ, and tympani, the score was largely re-instrumented by Mozart in 1789… The arrangement commonly used in England now is fundamentally that of Mozart, but with some additions sanctified by tradition. In the air “The trumpet shall sound,” Mozart has substituted a horn for the trumpet in the obbligato,- most probably because there was no trumpet player available at the moment. We have gone back in this respect to Handel’s original.

From programme notes for performance of Messiah in Free Trade Hall on December 19th, 1912

December 19th and 20th, 1929

The 1929 performances of Messiah took place just a week after the premiere of Constant Lambert’s Rio Grande that I wrote about in my last blog. The Hallé’s principal conductor Sir Hamilton Harty had played the piano in that performance, but here he took to the podium to conduct the choir and orchestra. The programme makes it clear that we are still in Mozart territory here, the work still being advertised in the programme as being ‘with additional accompaniments by Mozart’.

What is noteworthy here, however, is the calibre of the soloists that conductors such as Harty were able to attract to these annual performances of Messiah. Here we see four of the finest singers around at that time, particularly the wonderful Isobel Baillie. Though born in Scotland, she was raised in Manchester, attended Manchester High School and was very much a protogée of Hamilton Harty. She only ever once performed in opera, and was primarily, as here, a concert performer, specialising in British music. She sang in The Apostles and The Kingdom under Elgar’s baton, and was one of the 16 featured soloists in the premiere of Ralph Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music in 1938, singing the magical top A on the words ‘sweet harmony’. The proof of the quality of this quartet of soloists is that all of the other three, Muriel Brunskill, Parry Jones and Norman Allin, also performed in that premiere.

There is one final thing to mention about this concert that places it firmly in its period. Just ahead of the analysis of the work in the programme, the following request is made of the audience: ‘It is hoped that Ladies will not object to removing their hats when these obstruct the view of persons sitting behind’.

December 22nd, 1940

In 1940 we see again a single performance of Messiah but this time in an unusual venue. This was of course wartime, and this concert took place at the height of the Manchester blitz, a series of German bombing raids that began in August and reached their height at around this time, hence the fact that it is also sometimes known as the ‘Christmas blitz’. This presumably explains the fact that the decision was taken to put the performance on in the afternoon rather than the evening. Indeed, that very night, the night of the 22nd/23rd December, 272 tons of high explosive were dropped on Manchester.

This also explains the change of venue. The Free Trade Hall had been closed by bombing and indeed would not reopen, following major reconstruction, until 1951, so instead the performance took place in the Odeon Cinema on Oxford Street. Opened as the Paramount Cinema in 1930 at the height of the cinema building boom, this venue had room for 2,920 people on two levels as well as its own mighty Wurlitzer organ (which I assume was not used in the Messiah performance!).

By hook or by crook Messiah therefore still went on and once again attracted an impressive quartet of soloists which again included Isobel Baillie, this time under the baton of Malcolm Sargent, a regular conductor of Hallé Christmas Messiahs in the years that followed. A reminder, if any more were needed, of the cloud under which the performance took place, was the naming under the list of players of those members of the orchestra who were at that time serving in the armed forces.

This was also one of the first times the Hallé Choir had broadcast live on the BBC. The following announcement appeared in the Manchester Guardian on December 21st under the heading ‘BBC Week-End Programmes’:

To-morrow at 4.15 the Hallé Chorus and Orchestra, conducted by Malcolm Sargent, will broadcast a performance of the second part of Handel’s “Messiah” from a Northern concert-hall.

Manchester Guardian – 21st December, 1940

I particularly like the reference to ‘a Northern concert-hall’ – no sign of careless talk costing lives there!

Granville Hill reviewed the concert for the Guardian on Christmas Eve. Once again there were hints in his review at a more authentic Handelian as opposed to Mozartian approach to the work when he talks about the fact that ‘the rapid pace at which one or two of the choruses are taken nowadays is apparently accepted without demur even by the most conservative listeners. The one movement during which Dr. Sargent openly flouts tradition is the air “Why do the nations?” for here he refuses to admit the repeat, thus acting strictly in accordance with the marking in Handel’s own score.’ The shadow of the war hangs over the review, as shown in this description of the choir seeming to be triumphing in adversity:

The success of the choral singing on Sunday proves that in spite of war-time duties and difficulties about rehearsal the Hallé Choir possesses much of its wonted brilliancy in florid music. Occasionally in loud passages the tenor tone was hard, and the high notes of the basses lacked resonance, but splendour of style, mobility of technique, and precision of attack left no one in doubt as to the choir’s ability… The Christmas choruses and the two final numbers of the work were magnificently done, choral and orchestral tone being skilfully combined in fairness to the texture as a whole.

Granville Hill – Manchester Guardian, 24th December, 1940

Just as a footnote to this concert, I love the fact that 25 years later, this same venue played host to another set of fine Manchester musicians – The Hollies – as can be seen from this concert advertisement.

December 7th, 1969

Nearly 30 years on, and in one of John Barbirolli’s rare performances of Messiah we see a much more cogent expression of a period sensibility appearing in Barbirolli’s programme notes on the work. He agrees with Ebenezer Prout that ‘with our present sized choirs a performance in the original is hardly practicable,’ though he goes on to say that he should, ‘nevertheless, like to make the attempt some time in the future.’ Though he admits he is basing his performance on the Prout edition, he writes about some changes he has made in places in an attempt to get closer to Handel’s original intentions, listing the 7 sections that ‘will be performed in their original setting.’ These include two choral sections, ‘O though that tellest’ and ‘Let us break their bonds asunder.’ He is particularly critical of the Mozart/Prout tradition in his comments on ‘The people that walked in darkness’:

Of this particular piece I would like to say that with all my adoration of Mozart it should be made a criminal offence to play this number in any but its original form, for the bareness and austerity of the string octaves are a stroke of superb genius not to be tampered with.

Sir John Barbirolli writing in Messiah concert programme – December 7th, 1969

This performance also introduces us to another venue that regularly played host to Hallé Messiah concerts, the King’s Hall at Belle Vue. This was the nearest Manchester had to a modern day arena-style concert venue. Originally built in 1910 as a tea room for the Belle Vue Zoological Gardens, it was enlarged in 1928 and converted into a 7,000 seater arena venue, which along with classical and pop concerts also housed boxing matches, brass band competitions, and regular visits from circuses. It began to be used by the Hallé Orchestra in 1942 after the bombing of the Free Trade Hall, and continued to be used by them for the next 30 years, even after the reopening of the Free Trade Hall. The additional volume needed to fill such an arena presumably explains the presence in this Messiah performance not just of the Hallé Choir but also of the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus, regular collaborators with the choir and orchestra over the years.

December 12th, 2015

So now to the modern era, when the idea of Historically Informed Performance (HIP), of performing works as closely as possible to the original intentions of the composer, is very much in the ascendancy. Though the orchestra play modern instruments and the choir is much larger than that for the initial performances of Messiah back in 1741, the approach to Hallé performances of Messiah now is very much one of being as authentic as possible to Handel’s original intentions in terms of instrumentation, tempi and dynamic markings. To conduct the work, the Hallé now regularly engage choral specialists such as Stephen Layton and Sofi Jeannin, or HIP specialists such as John Butt, Christian Curnyn, and as in this case, Lawrence Cummings. Again the soloists are usually specialists in period performance, often with strong links with the conductor chosen to direct the performance.

Cummings came to this performance as someone long steeped in Handel and with an acute period sensibility, particularly with regard to his time as artistic director of the London Handel Festival. He directed this performance from the harpsichord, with a small orchestra of only 35 players very much in line with Handelian authenticity, with oboes, bassoons and trumpets present but none of the extraneous woodwind and brass of the Mozartian orchestrations. For this particular performance the choir were on the platform with the orchestra, a practice that has lapsed for the time being with the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and the increased size of the choir. However, at the time it gave a real sense of intimacy to the performance, a real sense of the choir being at one with the orchestra and being somehow back in time in 1741. Whether this style of performance will continue, one cannot tell. It may be that at some time in the future a conductor may want to experiment with the richer textures of a Mozart orchestration as its own form of period performance. What will be sure, however, is that whatever the style of performance it will very much be in the tradition of Hallé Choir performances!

References:

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

British Library, ‘Mozart’s version of Handel’s oratorio The Messiah https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/mozart-version-of-handel-messiah

Teri Noel Towe, ‘Messiah – Arranged by Mozart’ http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/works/handel/messiah/mozart.php

Emily C Hoyler, Handel’s Messiah: A Christmas Oratorio?’ https://divinity.uchicago.edu/sightings/articles/handels-messiah-christmas-oratorio-emily-c-hoyler

ArthurLloyd.co.uk, ‘The Odeon Cinema, Oxford Street, Manchester’ http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/ManchesterTheatres/OdeonParamountManchester.htm

Jess Molyneux, ‘Manchester’s Lost Concert Hall’ https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/nostalgia/gallery/manchesters-lost-concert-hall-hosted-22613520

Guardian Archive

Hallé Archive

Leave a comment