Wednesday 31st August, 2022 marked the thirteenth time that the Hallé Choir has appeared at the great British summer institution known these days as the BBC Proms, accompanying the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Choir in a performance of Edward Elgar’s sublime oratorio, Dream of Gerontius. This blog will look at the twelve previous performances in detail, the works sung, the circumstances in which they were sung and the critical response to them including, for the later concerts, personal testimony from current choir members.

Today the Proms are associated very much with the BBC and with the Royal Albert Hall, their home since the destruction of the Queen’s Hall by German bombing in World War Two. For most people the Proms are also associated with the flag-waving frenzy that is the Last Night of the Proms and the rituals associated with it, such as the singing of Land of Hope and Glory, Rule Britannia and Jerusalem, rituals that, as we will see, the Hallé Choir were able to experience at first hand on one memorable occasion. The Proms are however much more than the Last Night. Over the years they have grown into our premier classical music festival, featuring orchestras, choir and performers not just from all over the UK but from all around the world. The remit has also expanded to include many other styles of music – film music, jazz, folk, soul and R&B, and also, for the first time in 2022, music associated with video games!

This eclecticism, along with the informality and affordability that has always been an important feature of the Proms, has been present since their beginnings back in the 1890s. Though the name of Sir Henry Wood was intrinsically associated with the Proms in their early years, they were actually begun by the impresario Robert Newman, with financing provided by George Cathcart, a wealthy physician, who agreed to put up money on condition that Henry Wood be employed as the sole conductor of the concert series. Wood had made a living conducting for opera companies such as the D’Oyly Carte and Carl Rosa companies, but it was with the Proms that he really made his name, and his association with them continued with them until his death in 1944. An orchestra was engaged, calling itself the Queen’s Hall Orchestra, and the first of “Mr Robert Newman’s Promenade Concerts” took place on August 10th, 1895.

In a letter to Wood, Newman outlined the philosophy that lay behind his concept of the Proms: ‘I am going to run nightly concerts and train the public by easy stages. Popular at first, gradually raising the standard until I have created a public for classical and modern music.’ Whilst seating was available, what made them specifically ‘Promenade’ concerts was the fact that a large standing area was provided, at low cost, in which concertgoers could walk around, eat, drink, and even smoke during the concerts. This aspect of the Proms has continued to this day, with cheap arena and gallery tickets being provided from people who are prepared to stand through the concerts (though smoking has been banned since 1971!).

The programmes Newman and Wood put together were long and varied, and were initially a mixture of light music and standard classical repertoire. However, as Wood, always a champion of new music, became more involved directly with the programming, they increasingly included more challenging works from the emerging composers of the early 20th century. As an example, Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, a early modernist classic, received its world première at a Promenade Concert in 1912.

The music publishing company Chappell took over the financing of the Proms after the First World War but when Newman died in 1926 they withdrew their support and the Proms seemed doomed. It was only in following year when the recently formed British Broadcasting Company (later, of course, the British Broadcasting Corporation) took over the running of the Proms that their future was secured. Wood continued as conductor and planner, but though the concerts continued to be staged at the Queen’s Hall, the performing group was now re-billed as ‘Sir Henry J. Wood and his Symphony Orchestra’. This arrangement that continued until 1930 when the BBC Symphony Orchestra was formed, and this orchestra has been the mainstay of the Proms ever since. Though the concert series is generally now termed the BBC Proms, not least by the BBC itself, its official title is still the ‘Henry Wood Promenade Concerts’, and each year a bust of Wood, retrieved from the rubble of the bombed-out Queen’s Hall, is placed in front of the organ at the start of the Proms series.

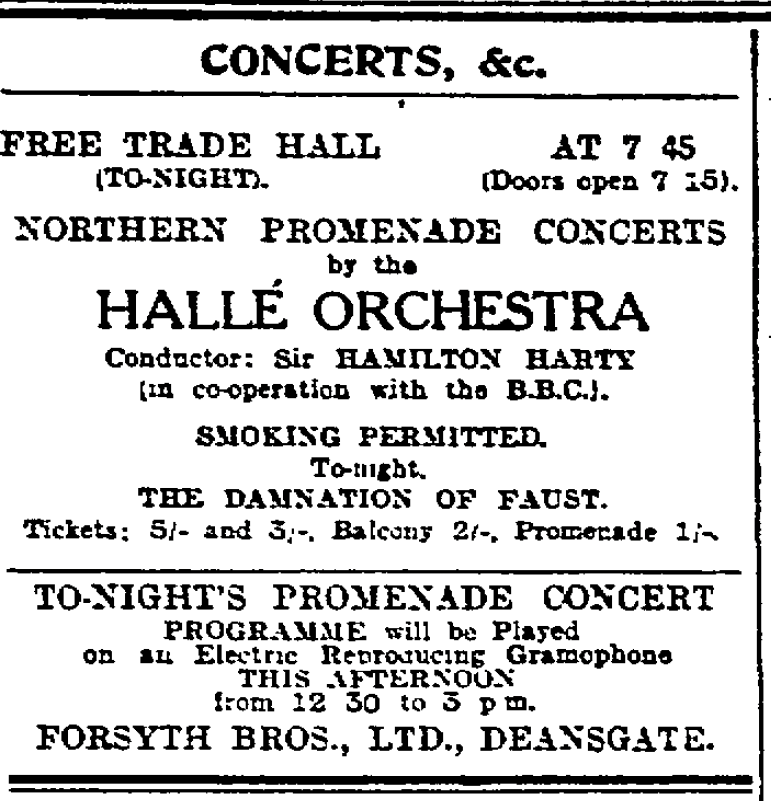

1930 was also the year that the Hallé Choir first entered Proms history. Having taken over the running of the Proms the BBC was keen to repeat the ‘promenade’ formula elsewhere in the country, and as an experiment put on a season of what they termed ‘Northern Promenade Concerts’ in the early summer of that year, with two weeks of concerts in Manchester followed by one week in Liverpool and another in Leeds. To perform in the concerts they engaged the Hallé Orchestra and their chief conductor of the previous ten years, Sir Hamilton Harty. The Manchester Guardian previewed the concerts as follows:

The B.B.C. and the Hallé Concerts Society announce that they have concluded negotiations for the series of Northern Promenade Concerts in Manchester, Leeds, and Liverpool…

The idea of the concerts, as the official announcement puts it, is to offer to Northern audiences opportunities of hearing music of a high standard during the summer months at very popular prices… These Promenade Concerts will be used not only as contributions to the Northern England programmes but also to National and other wave-lengths.

Manchester Guardian, April 1st, 1930

The North Regional Director of the BBC, a Mr Liveing, was quoted in the Guardian on May 16th as being ‘animated by a very genuine desire to promote northern orchestral interests for their own sakes.’ He was ‘anxious that they should be a success’ and confident that ‘if they are they may lead the way to other schemes.’

Indeed the concerts were an apparent success, with 18,000 people attending the Manchester concerts. A columnist in the Guardian, writing on June 7th, was confident that ‘public response had already been so good that it may be taken for granted that the Hallé Committee and the British Broadcasting Company will have every sympathy with the desire that such concerts should become a permanent feature of our musical activities.’ However, the BBC soon abandoned the experiment, claiming heavy losses, which led to considerable bad blood with the Hallé Concerts Society, whose chair E.W. Grommé made much of the fact that the orchestra had been engaged at much less than its normal rate, with Harty in particular being paid a third of his normal fee.

Despite this, the concerts remain as part of the official Proms performing history, such that the two concerts that the Hallé Choir were involved with can rightly be claimed as the choir’s first Proms performances. This first performance, on May 28th, was an opera concert featuring extracts from, amongst others, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, Borodin’s Prince Igor (the Polovtsian Dances) and Act 3 of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger. Neville Cardus, that doyen of the twin arts of music and cricket, gave a typically colourful description of the choir’s contribution to one of the extracts, along with an interesting assessment of the success or otherwise of the Proms experiment:

The singing of the chorus [in Boris Godunov] could be enjoyed up to a point, but the sense of a multitudinous palpitation, of a quicksilver passion running through massed, untamed blood was entirely missing…

An enthusiastic and fairly numerous audience enjoyed everything. But, so far, the promenade spirit has not been captured. There is perhaps too little room for us to promenade. At Queen’s Hall, in late summer, the whole of the ground floor is available for a free-and-easy stroll between one piece and another an during the interval. Last nights audience was very polite and reserved. A bold man, but nobody less than bold, might have dreamed of talking to a perfect stranger. Manchester apparently takes its music in summer as seriously as it takes its county cricket.

Neville Cardus – The Guardian, 29th May, 1930

The second concert on June 4th was taken up with a performance of Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust that also featured the boys of Manchester Cathedral Choir and a stellar cast of soloists that included Isobel Baillie as Marguerite and Parry Jones as Faust. This time Cardus was much more taken with the choral sound: ‘The chorus combined very finely pace and power, blend and expressive transition. In the celestial scene at the close the vocal texture was sweetened by the young voices of the boys of the Manchester Cathedral Choir. Sir Hamilton Harty conducted like a man possessed.’

It would be fifty years before the Hallé Choir performed again in the Proms, appearing in what was for a long time the traditional performance of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony on the night before the Last Night. The Hallé Choir always seem to have been fortunate in the choice of soloists they have sung alongside in the Proms, and this, the choir’s first appearance at the Royal Albert Hall, was no exception with a cast that comprised Heather Harper, Alfreda Hodgson, John Mitchinson and Robert Lloyd. The concert, which also included Beethoven’s 1st Symphony, was conducted by James Loughran, who had succeeded John Barbirolli as the Hallé Orchestra’s chief conductor in 1971 and who made many appearances at the Proms over the years including five at the Last Night (of which more in a moment).

Maybe because of its place in the season on the Friday immediately before the Saturday of the Last Night, critical reviews of the concert seem to be impossible to find. However, we do have the memories of choir member Vin Allerton to call on. His memories tally with many who have suffered the back stage facilities at the Royal Albert Hall!

The only clear memory I have of the event is being struck how tatty the hall was, particularly back stage, with almost no changing space, and no privacy – I think we had to change in a bar, which was open to the public. This was, I believe, the first time the choir had sung at the Proms in London.

Vin Allerton

The following year the choir returned, and this time went one night better with an appearance at the Last Night of the Proms itself, unusual because the Last Night is usually exclusively the choral domain of the BBC Symphony Chorus and the BBC Singers. Choir members Susan Oates, Kath Renfrew and Vin Allerton all have the same recollection of why this happened, though interestingly the official histories of the Proms make no mention of this 1981 deviation from the norm. Here’s Susan:

As far as I can remember we were asked to sing for the Last Night of the Proms because Jimmy Loughran was conducting and the BBC Symphony Chorus were unavailable because they had booked themselves out for a foreign tour so he suggested that ‘his’ choir were available and could do it.

Susan Oates

The first half of the concert included, along with Elgar’s Cockaigne overture and Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending with Iona Brown as soloist, a suitably rumbustious piece for such an occasion, William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast with David Wilson-Johnson as the baritone soloist. Vin Allerton remembers the difficulties of combining the rehearsal with the requirements of television, plus a salutary note on the importance of detailed planning before a trip to London:

In those days, the whole concert was broadcast live on Radio 3, but only the second half was televised. I recall that we had 3 hours rehearsal scheduled at the RAH, but that about 2 hours was spent on the second half items, mainly for the cameras; so we only had about an hour’s rehearsal time with the BBCSO on the Walton, and they were a rather different kettle of fish to the Hallé of the time (their brass was much louder). However, we had sung Belshazzar in 3 performances in April/May 1981 at the Free Trade Hall, so we were pretty au fait with the work. My other standout memory is that I left my copy of the Walton score at home, but was able to buy a copy in London before the rehearsal.

Vin Allerton

Vin’s purchase obviously paid off and the performance of Belshazzar’s Feast was very well received by the critics. Paul Griffiths in the Times thought it ‘… a performance under James Loughran which showed up all the ironic glee and artifice beneath the pomp and savagery,’ and Edward Greenfield in the Guardian thought it ‘made a splendid Last Night work, noisy but musically meaty.’ His only issue was with the amount of sound, such that ‘with seats at a premium we had to make do with a chorus of 120 or so (this year Loughran’s Hallé Choir lustily down from Manchester) where the Royal Albert Hall serves best with twice that number.’

As for the televised part of the concert YouTube has a brief excerpt from the beginning of the second half that includes some glimpses of the choir and the singing of Land of Hope and Glory. To Kath Renfrew such was the occasion that the atmosphere remains more vivid in the memory than what was actually sung:

I can’t remember now what we sang, apart from the usual second half pieces… I just remember that it was a fantastic atmosphere and a great thrill to be able to sing at the Last Night and see all the flag-waving promenaders in front of us!

Kath Renfrew

Another thirteen years were to elapse before the Hallé Choir, or at least the sopranos and altos thereof, were to appear again at the Proms – the era of regular appearance would not arrive until the advent of Mark Elder. By 1994 the Hallé’s chief conductor was Kent Nagano, an era in the orchestra’s history that was interesting artistically but somewhat less than interesting financially. However, he must have been very conscious of the orchestra’s heritage and a programme was put together for August 5th as a tribute to John Barbirolli that included works by Elgar, Berg and Mahler that were associated with Nagano’s illustrious predecessor. The final item on the programme was the work premiered by the Hallé in 1953 that was covered in the last blog, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antartica.

This would have been a work made for the wide open spaces of the Royal Albert Hall and in particular the mighty Albert Hall organ. Meirion Bowen certainly thought so, reviewing the concert for the Guardian, believing the orchestra ‘made a strong case, too, for Vaughan Williams’s Sinfonia Antartica, picturesque tableaux evoking Scott’s heroic endeavour in a bleak landscape. Organ, offstage women’s chorus and solo soprano (Susan Gritton) were tellingly exploited.’

‘Offstage’ in this instance meant the gallery, where the women’s voices were joined by the soprano soloist. Daphne Dawson describes the experience well:

It was a hot day and we didn’t sing in the normal choir seats, but in the ‘Gods’ – where I had once promenaded, the stalls area being full, some ten years before. This time we women sang in the area to the left of the promenaders while the soloist was opposite us on the right of them. I think everyone enjoyed our antarctic wailing, feeling quite a bit cooler afterwards somehow!

Daphne Dawson

1999 saw the appointment of Mark Elder (later Sir Mark) as chief conductor of the Hallé Orchestra, a moment in the orchestra’s history that in retrospect stands equal in importance to Charles Hallé’s initial decision to create the orchestra and the appointment of John Barbirolli as chief conductor in the midst of the Second World War. I will cover the effect this had on the choral output of the Hallé in more detail in a later blog post, suffice to say that in 2001, when the whole choir was invited once more to sing at the Proms, the Hallé Choir was in something of a hiatus that would only be settled by the appointment of James Burton as Choral Director the following year.

The programme that Elder chose for his first Proms appearance with his new orchestra on July 22nd, 2001 reflected his background in opera (he had been musical director of English National Opera from 1979 to 1993 and also had close links to the Royal Opera House and Glyndebourne). It consisted of selections from various Verdi operas including a performance of the complete Act 2 of Aida. A large chorus was assembled for the occasion, not just members of Hallé Choir but also members of Leeds Festival Chorus and the London Symphony Chorus.

Hilary Finch, writing in the Times, knew that this was a very different Hallé on display: ‘This minutely rehearsed performance [of the Sinfonia from Nabucco] not only indicated thrilling what might lie ahead, but revealed how the Hallé Orchestra is already a transformed creature at the start of Elder’s first season there.’ Erica Jeal in the Guardian described how the ‘massed ranks’ of the assembled choirs when they finally got a chance to shine in Aida ‘filled the hall with thrilling sound.’

By 2005, the time of the choir’s next Albert Hall appearance on July 24th of that year, James Burton had revitalised the choir and also added an extra element into the choral mix, the newly-formed Hallé Youth Choir, part of a wider project to expand the Hallé’s choral offering that now includes a children’s choir, various training choirs, a community choir and a long-standing workplace choirs initiative.

Mark Elder had realised on taking over the orchestra that he needed to bring it back to one of its core specialities from the time of Barbirolli, quality performances of the British orchestral and choral repertoire, and in particular the music of Edward Elgar. And what better way to emphasise this commitment than a performance of Elgar’s mighty Dream of Gerontius? With the massed ranks of the Hallé Choir, the London Philharmonic Choir and the Hallé Youth Choir (singing the semi-chorus), a fine cast of soloists that included Alice Coote, Matthew Best and, as Gerontius and drafted in very much at the last moment, the American tenor Paul Groves, a live television audience was given a real treat. My own experience of that weekend is unusual. I actually appeared in the Prom the night before, singing with Chester Festival Chorus in the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic’s performance of Vaughan Williams’ Sea Symphony, itself a wonderful experience, and travelled back up north the following day just in time to catch the Hallé’s live broadcast. I think it was watching that broadcast that made me realise that one day I had to join the Hallé Choir!

That weekend was also memorable in other, darker ways. A few weeks earlier, on the day after London had been awarded the 2012 Olympics, the city had been hit by a number of coordinated terrorist attacks that became known as the 7/7 bombings. Another terrorist incident occurred a few days before the concert and so the whole city was on high alert. Graham Worth describes the effect this had on the choir and on him personally:

Under the circumstances we were individually given the opportunity not to take part but I think pretty much everyone turned up and I remember hugging my wife and young children and wondering if I’d see them again, but determined, like everyone else, not to let terrorism beat us. I think what impressed me the most was the courage of the parents of the members of the Youth Choir – it’s one thing making that decision as an adult, but letting your children go must have been agonising for them. Nobody was taking the tube or using buses, they had sniffer dogs checking for bombs in the Albert Hall, and police sirens were going off left, right and centre, with concerns about further attacks (I think there was a suspicious package on HMS Belfast or maybe The Cutty Sark among others).

Graham Worth

Once the performance started, however, any such fears vanished. Here’s Graham again, on the way the Youth Choir transformed the sound of the concert:

Prior to this concert I’d sung in the semi chorus for Gerontius on a number of occasions and was a little disappointed when told that the Youth Choir would sing the part but then I heard the heavenly purity of their voices and had no regrets!

Graham Worth

For another choir member, the experience of being on live television was a standout memory:

For the 2005 Dream of Gerontius several of us sopranos were lucky enough to be behind the harps, a good spot to feature on the TV cameras. I’m afraid they caught me making suitably evil faces during the Demons’ Chorus.

Daphne Dawson

Paul Brennan’s abiding memory of the concert shows how a work such as Gerontius can help help both public and private grief:

My Prom memory of Dream of Gerontius is that I and a couple of choir members met Paul Groves in the labyrinth of corridors after the performance. We were chatting about how much we enjoyed the performance and congratulated him on his very moving performance. He said that his father had died a short time before the concert and the text seemed so appropriate to his own feelings at that time.

Paul Brennan

The critics were suitably impressed by the performance. Andrew Clements in the Guardian commented on how Elder’s operatic experience informed the performance and enthused over the ‘huge set pieces’ that ‘had all the necessary presence – the choral sound at the end of Praise to the Holiest was simply glorious – with nothing speciously pious about it either.’ Geoff Brown in the Times felt that ‘top marks for blended sound, except when shouting in exultation’, went to ‘the throats united for Mark Elder’s Elgar: the Hallé Choir, the London Philharmonic Choir, the Hallé Youth Choir’, believing to be ‘a classy performance all round.’

The Hallé Choir now settled into a pattern of Proms performances every few years that continued until the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020. 2009 saw a performance of Mendelssohn’s choral Symphony No. 2, known as Lobgesang or ‘Hymn of Praise’, first performed by the orchestra and choir back in the 1860s under Charles Hallé. This performance, where the choir were joined once again by the Hallé Youth Choir, had been trialled by the choir in Valencia, where the Hallé had travelled to perform all five of his symphonies as part of the Mendelssohn bi-centenary celebrations.

The Proms performance on July 30th was James Burton’s swansong as Hallé Choir Director following a fruitful seven-year stay that laid the basis for the choir we see and hear today. Judging by the reviews, he had prepared the choirs well. This extract from Hilary Finch’s review in the Times is worth quoting in full:

The massed presence of the Hallé Choir and the Hallé Youth Choir arose as one, and sung with raw and robust enthusiasm their opening chorus, All that Breathes, Praise the Lord!… Elder drew maximum effect from the juxtaposition of the great dawn chorus and the hushed opening of the hymn Nun Danket alle Gott, before choral praises rolled over each other in the final chorus.

Hilary Finch – The Times, August 1st, 2009

Martin Kettle in the Guardian was slightly more concise, writing that ‘the Hallé Choir gave their all’.

Note that video of the choir’s performance is available on YouTube, but couldn’t be embedded in this blog post. However, it can be found by following this link: https://youtu.be/WWtGdNsCK5I The choir’s performance of Lobgesang starts at about 1 hour 3 minutes in.

By 2012 Mark Elder’s submersion in the music of Elgar had resulted in a number of fine recordings, including recordings with the Hallé Choir of two oratorios, Dream of Gerontius and The Kingdom, and his later choral gem, The Music Makers. A further recording of his other great oratorio, The Apostles, was soon to follow, based on a performance given early in 2012 in the Bridgewater Hall in Manchester. It was this work that was reprised on the 10th August as part of the 2012 BBC Proms. Another top-class selection of soloists, including Alice Coote and Paul Groves from the earlier Gerontius performance, Jacques Imbrailo as Jesus and Clive Bayley as Judas, joined the Hallé Choir, Hallé Youth Choir and London Philharmonic Choir. In a typically inventive Mark Elder conceit, the semi-chorus of Apostles was performed not by a section of the tenors and basses of the choir as would normally be done, but by a group of students from the Royal Northern College of Music.

The 2005 performance of Gerontius followed close on the heels of the awarding of the 2012 Olympics and the terror attacks that followed. For the 2012 performance of The Apostles, London was en fête – the Olympics were actually in town. This was my first Proms performance with the choir having joined in late 2009 and most of my non-musical memories of the occasion are tied up with the Olympics. I vividly remember walking through Hyde Park in warm sunshine on my way to the Albert Hall for the afternoon rehearsal and seeing the men’s long distance swim in full swing in the Serpentine, and the following morning walking across the Millennium Bridge with my nephew to watch the men’s marathon runners go past St. Paul’s Cathedral. Daphne Dawson has similar memories, showing how much fun our brief trips to the Proms can be:

It’s always enjoyable to sing at the Proms with such a lively audience just in front of you. It’s good to be in that lovely building and to have a chance to see that bit more of London too. I managed to see a little of the Olympics in 2012, and completed my walk round London, the Capital Ring, after our performance in 2016 – great music and some glorious green spaces (Richmond Park amongst others)… the very best of a capital city.

Daphne Dawson

This time around, the reaction from the critics was mixed. Hilary Finch in the Times was wholly enthusiastic, writing that ‘Elder’s performance reaffirmed the stature of this once marginalised piece… Elder creates a seamless garment of orchestral and choral writing, with one emotionally charged confrontation hard on the heels of the next’, and Edward Seckerson in his blog thought ‘the choral singing from the combined Hallé and London Philharmonic choirs was thrillingly unanimous and rhythmically precise despite such large numbers and the clarity and freshness of young voices – the Hallé Youth Choir – brought something really resonant to the Mystic Chorus of “The Ascension”.’ However, the reviews of Guy Dammann in the Guardian and Michael Church in the Independent were coloured by their lack of empathy for the work itself, a ‘second-rate choral extravaganza’ according to Dammann, and full of ‘high-flown Edwardian religiosity’ according to Church. However, both were forced to admire the performance. For Church ‘Elder’s control was so finely calibrated that the transitions between fortissimo choral shouts and delicate instrumental solos felt entirely natural’, and Damman wrote that ‘Mark Elder, always a generous and insightful Elgarian, led the Hallé, on superlative form, backed by massed ranks from the Hallé Choir and Youth Choir together with the London Philharmonic Choir.’

The work chosen for the Hallé Choir’s 2015 Prom was alluded to in my previous blog about the choir’s association with Ralph Vaughan Williams. This was the composer’s 1926 oratorio Sancta Civitas (‘The Holy City’), a work much loved by the composer himself but somewhat neglected since his death – indeed this would be the first ever performance of the work at the Proms. The neglect may partly be explained by the forces required to perform the piece – a main choir (Hallé Choir and London Philharmonic Choir for this performance), a semi-chorus (Hallé Youth Choir), a children’s choir (Trinity Boys’ Choir, singing from the gallery), a baritone soloist who only sings for the first two-thirds of the piece (Iain Paterson) and a tenor soloist who only sings a few bars right at the end (Robin Tritschler). For all this, it is still to my mind a deeply affecting piece, a musical evocation of words from Revelation about the fall of Babylon and the creation of a new heaven and a new earth which has moments of profound beauty.

The work is above all a satisfying choral experience, as noticed by Chris Garlick, writing for the Bachtrack blog: ‘What committed singing there was from all the choirs (Halle Youth Choir, Trinity Boys Choir, Halle Choir and the London Philharmonic Choir), relishing the sensuous quality of the music and rising to a final intense climax supported by the organ, with everyone singing for all they were worth.’ Michael Church in the Independent relished the spatial element of the performance: ‘With Ian Paterson as the baritone, this performance was punctuated by majestically dramatic surprises, as the focus moved between vast blocks of sound coming from all sides of the auditorium including the gallery.’ For Hugo Shirley in the Daily Telegraph, the choirs ‘all sang their socks off’! The choir even got what was possibly their first ever review in the New York Times, with David Allan describing how ‘encircling the hall with singers from the Hallé Choir and Youth Choir, The Trinity Boys Choir and the London Philharmonic Choir, Mr. Elder brought out both its enormity and, somehow, its intimacy.’ Finally, Richard Morrison in the Times praised the ‘ecstatic polychoral writing, engulfing us like vast tidal waves.’

The second half of the concert, a performance of Elgar’s Symphony No. 2, was shown on BBC Four. However the whole of the concert was recorded, and in a first for the choir the performance of Sancta Civitas was made available on-line (and is now available on YouTube).

What of the work itself? Martin Kettle in the Guardian felt that the case for the work had been made: ‘…these were near ideal conditions for the Hallé players and singers to make the case for this important piece… They succeeded impressively.’ However, performances of the work since 2015 have been few and far between and a planned recording of the work by the Hallé fell victim to the pandemic. Maybe one day it will be held in higher regard.

The choir did not have to wait long for their next performance at the Proms. The powers that be at the BBC Philharmonic, Manchester’s other great orchestral institution (or should that be Salford’s?), had heard us sing Beethoven’s monumental Missa Solemnis with Mark Elder in the Bridgewater Hall during 2015, and possibly as a result we got an invitation, along with the Manchester Chamber Choir, to sing the work with the BBC Philharmonic and their former principal conductor, Gianandrea Noseda, at the 2016 Proms. Knowing what a gruelling and yet satisfying sing the work is, we knew what an experience it would be. It would also be overwhelmingly a Manchester experience, a point made by the then choir chair, Merryl Webster, in a interview with the online news feed Mancunian Matters: ‘It’s really important that Manchester is featured in the Proms, so we have to go and sing our socks off down there!’

And sing our socks off we did, supporting another magnificent cast of soloists that included future Last Night of the Proms soloist Stuart Skelton. Fiona Maddocks in the Guardian was particularly impressed by both the choirs and the Mancunian overtones: ‘A performance by the joint forces of the Hallé Choir, the Manchester Chamber Choir and the BBC Philharmonic – thus joining so many excellent Manchester-based musicians in joyful concord – was a highlight of the first week… [Noseda’s] former orchestral colleagues, as well as the 160-strong chorus, responded deftly to his electrifying mix of clarity and enigma.’ Anna Picard in the Times thought ‘the urbanity of the orchestral playing was beautifully contrasted with the votive intensity of the chorus in the Kyrie’, and Nick Kimberley in the Evening Standard felt that ‘it was the chorus that deserved star billing… the 160-plus members of the Hallé Choir and Manchester Chamber Choir articulating every word with minutely calibrated passion.’

And so the last time the Hallé Choir featured at the BBC Proms, though on this occasion it was only a sub-section of the sopranos and altos of the Hallé Choir and Hallé Youth Choir that performed. It was also the only Hallé Choir performance at the Proms that I have attended as a paying customer! The choir were to sing Debussy’s early cantata La Damoiselle Élue, a setting for choir and two soloists (Sophie Bevan and Anna Stéphany) of a translation of Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s poem ‘The Blessed Damozel’, in a programme that also included Wagner’s Tannhäuser overture and two works by Stravinsky, Song of the Nightingale and the 1945 suite taken from his ballet Firebird.

The choir, though small in number, were an effective presence. Alan Sanders, writing on the online review site Seen and Heard International, thought ‘the pure-toned voices of the ladies of the combined Hallé Choir and Hallé Youth Choir provided just the right gentle, ethereal contribution’, whilst Young-Jin Hur on Bachtrack described how ‘Katherine Baker’s flute had a touch of brazen songfulness, yet equally impressive were how the Hallé Choir and the Hallé Youth Choir projected a firm presence while maintaining a transparent tone as to allow all instruments discernible.’

That was not the choir’s only contribution to proceeding, however. In another example of innovative Mark Elder programming, the decision was made to start the performance of Firebird with the choir singing in unison two of the Russian folk songs quoted in the work, as taken from Rimsky-Korsakov’s book of 100 Russian Folk Songs, and conducted from within the orchestra by choral director Matthew Hamilton. Young-Jin Hur praised the idea: ‘It was a fine programming decision, elucidating the Russian spirit underlying of a work Diaghilev called “the first Russian ballet.”’

This then is the history of the Hallé Choir at the Proms, an association that goes back nearly 100 years and that has included both some of the great works in the choir repertoire as well as a number of relative rarities, and that has also moved from the musical high jinks of the Last Night to the quiet reflection of works such as Sancta Civitas and La Damoiselle Élue. Whatever the quality or nature of the work, however, the commitment and quality of performance appears to have been almost universally high and in their many trips south the Hallé Choir have been great ambassadors for Manchester and its music making. Let us hope that many more such trips await in the future.

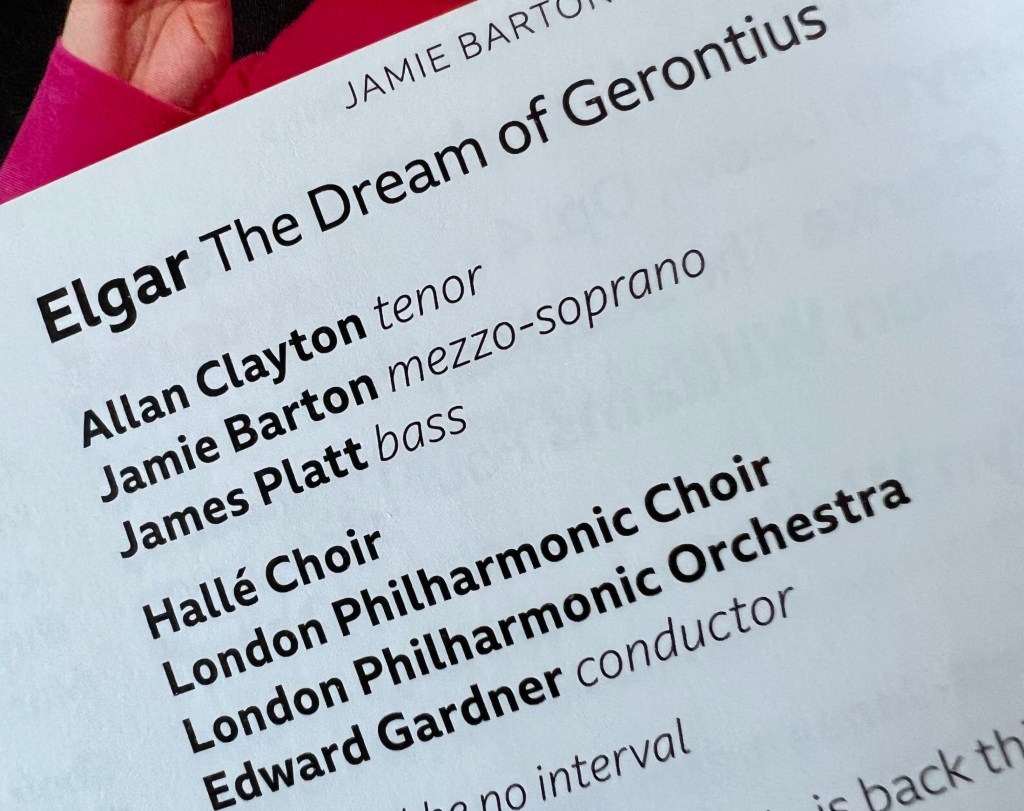

Postcript: The performance of The Dream of Gerontius in August 2022 was, if the immediate reviews are to be believed, a great artistic success. It certainly felt like that from the choir seats as the nearly 300 singers of the combined Hallé and London Philharmonic Choirs filled a packed Royal Albert Hall with the sound of Elgar, helped by three soloists on top form – Allan Clayton, Jamie Barton and James Platt. The ground work was done at a joint rehearsal the night before in the unfamiliar surroundings of the Fairfield Halls, Croydon, with the conductor Ed Gardner mediating as the London Philharmonic Orchestra on the platform and the choirs in the audience seats faced off against each other over the course of three hours.

As for the concert itself, Richard Morrison in the Times summed up the effect of the choral sound, especially at the emotional high-point of the piece: ‘The combined lungs of the London Philharmonic Choir and Hallé Choir sounded terrific, whether whispering rapt prayers round the dying man or turning the C major blaze of Praise to the Holiest into a full-throated yet perfectly focused roar of exultation.’ Andrew Clements in the Guardian was of similar mind: ‘The choral sound from in excess of 250 voices was majestic, even if with that number of singers the trickier corners of the Demons’ Chorus were not ideally nimble; the hush of the final pages was beautifully controlled and, like the rest of the performance, was never pushed or overplayed by Gardner.’ Special praise in many of the reviews, however, was given to the sopranos, as from Rupert Christiansen in the Daily Telegraph: ‘And special praise to the sopranos of those two wonderful choirs: their cry of ‘Praise to the holiest’ as Gerontius crosses the threshold into the divine presence was absolutely electrifying – a nuclear explosion of dazzling light that could have blown the National Grid.’

References:

Cox, David, The Henry Wood Proms (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1980).

Doctor, Jennifer R., Wright, David C. H., and Kenyon, Nicholas, The Proms: A New History (London: Thames & Hudson, 2007).

Kennedy, Michael, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960).

plus the Times Archive, the Guardian and Observer Archive, and the various newspaper and internet review sites quoted

Special thanks to the choir members who contributed to this blog post

Leave a reply to lordgnome1 Cancel reply