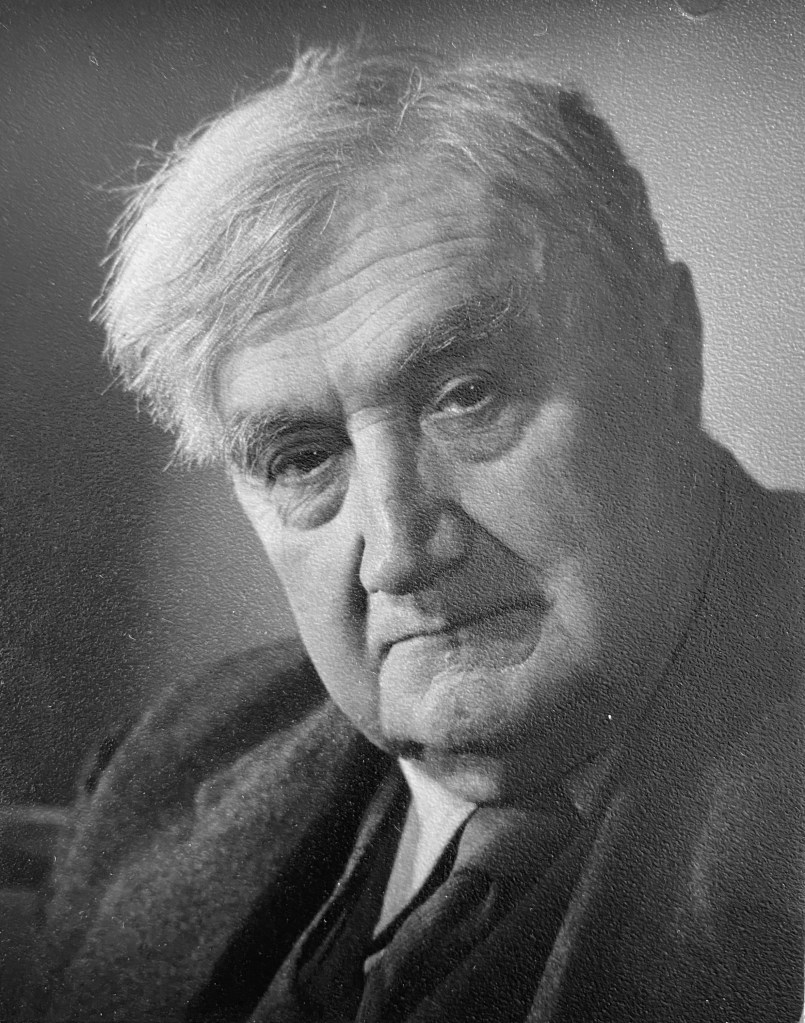

In my first two-part blog I outlined how various disparate groups of singers in the Manchester of the 1850s coalesced into what began to be called as Mr Hallé’s Choir and which now is known to all as the Hallé Choir. I will revisit the early years of the choir in future blogs, but for now I want to celebrate, in the year that marks the 150th anniversary of his birth, the choir’s relationship with Ralph Vaughan Williams, arguably the most influential English composer of the 20th century, and certainly one of the greatest symphonists of that century. I will show how from rocky beginnings, the choir’s relationship with the music of Vaughan Williams began to flourish, particularly in the years immediately before the composer’s death in 1958, and continues to thrive today in the hands of the Hallé’s current principal conductor, Sir Mark Elder.

Ralph Vaughan Williams was born on October 12th, 1872 in the small Gloucestershire village of Down Ampney, where his father was serving as vicar. On the death of his father when he was only two, his mother Margaret took him and his siblings to live at her family home, Leith Hill Place in Surrey, high on the North Downs and with distant views of the Sussex coast. Margaret was born into the Wedgwood family and was also related to the Darwins (her mother was Caroline Darwin and her uncle Charles Darwin). Thus, whilst his upbringing was very much a privileged one, it was also one informed by the liberal views of those two families, and throughout his life Vaughan Williams would espouse radical and socialist views and fight against any élitist view of his art, endeavouring to bring it to the widest possible audience.

With the encouragement of his aunt, Sophy Wedgwood, he began to show early musical talent, writing his first piece of music at the age of 5, and whilst at school at Charterhouse he developed this love for music, and specifically for composing (he never excelled as a performer on either of his chosen instruments, piano or viola). This led him in 1890 to enrol at the Royal College of Music where he studied composition under Charles Hubert Parry, who instilled within him an appreciation of the English choral tradition stretching back to the Tudor composers Byrd and Tallis. Parry’s own choral compositions were also a huge influence on Vaughan Williams’ early attempts at writing for the choral voice.

Following parental pressure he withdrew from the RCM in 1892 to study for a History degree at Trinity College, Cambridge. During his time in Cambridge he found himself influenced by radical contemporaries such as Bertrand Russell (who instilled in him an appreciation of the work of the transcendental American poet Walt Whitman), and also met and fell in love with Adeline Fisher, who became his first wife in 1897. On graduating, the call of music drew him back to the RCM, where he now studied composition with Charles Villiers Stanford. Vaughan Williams’ relationship with Stanford was somewhat stormier than that with Parry, but Stanford nonetheless became a great early champion of Vaughan Williams’ music.

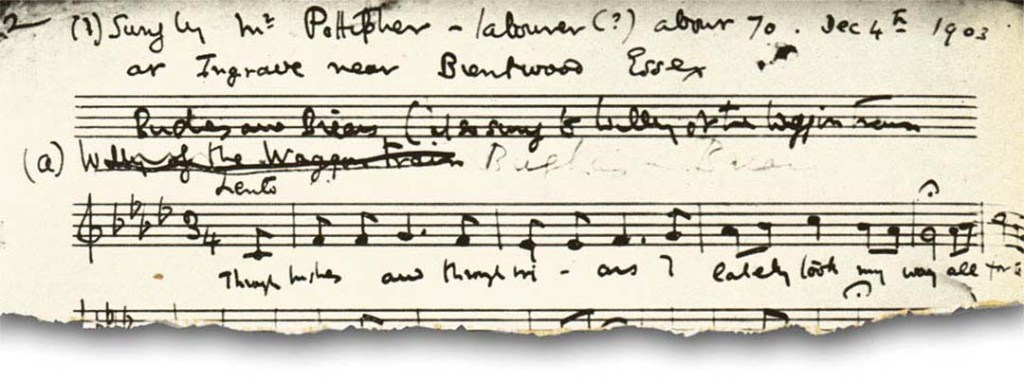

The most significant event of Vaughan Williams’ second spell at the RCM, however, was undoubtedly meeting fellow student Gustav Holst, with whom he formed an enduring musical friendship which lasted until Holst’s early death in 1934, the two constantly criticising and encouraging each other’s compositional endeavours. In the early 1900s the two also used to go on expeditions together collecting folk songs from towns and villages throughout England. This followed a seminal moment in Vaughan Williams’ musical development in 1903 when, on a visit to Ingrave in Essex, he heard the retired farm labourer Charles Potiphar sing the folk song Bushes and Briars, igniting a love for the tunes and modalities of folk music that began to infect his compositions, driving out the Germanic elements that had been influenced by Parry and Stanford. Nowhere was this more evident early on than in the tunes he selected for the English Hymnal of 1906, which he had been asked to help edit by Percy Dearmer, amongst which were original compositions such as the beautiful Down Ampney tune to which he set the hymn Come Down, O Love Divine, but also arrangements of the folk tunes he had collected, such as John Bunyan’s hymn He Who Would Valiant Be, which he set to the tune of the folk song Our Captain Cried All Hands.

The final piece in Vaughan Williams’ musical jigsaw came in 1907 at the age of 35 when, believing his music needed a little ‘French polish’, he went to Paris to study with Maurice Ravel, who was three years his junior. By the end of the decade, the influences of Tudor polyphony, English folk song and a healthy dose of Ravel’s variety of French impressionism had begun to form the mature voice of Vaughan Williams as a composer, nowhere more so than in the A.E. Housman song cycle On Wenlock Edge, and the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, which was premiered to great acclaim in Gloucester Cathedral in 1910. That same year also saw the premiere in Leeds by the Leeds Festival Chorus of a full-blown choral symphonic setting of words by Walt Whitman that he called A Sea Symphony, using excerpts from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and the metaphor of the sea to chart the journey of the human soul into the unknown. It followed a smaller scale Whitman setting on a similar theme, Toward the Unknown Region, that had been premiered by the same forces two years earlier.

Whilst the two heavily chromatic Whitman pieces tended to hark back to the influences of Parry and Stanford, this new mature Vaughan Williams began to assert itself, charting a musical path through the 1910s and 1920s that may not have been as revolutionary as the music of Schoenberg and the other composers of the Second Viennese School, but was like theirs very much a contemporary, albeit very English, response to the changing world of the new century. Nowhere was this more evident than in his third symphony, the Pastoral, and its genesis in the trenches of the First World War, which Vaughan Williams had experienced at first hand as a stretcher bearer and ambulance driver.

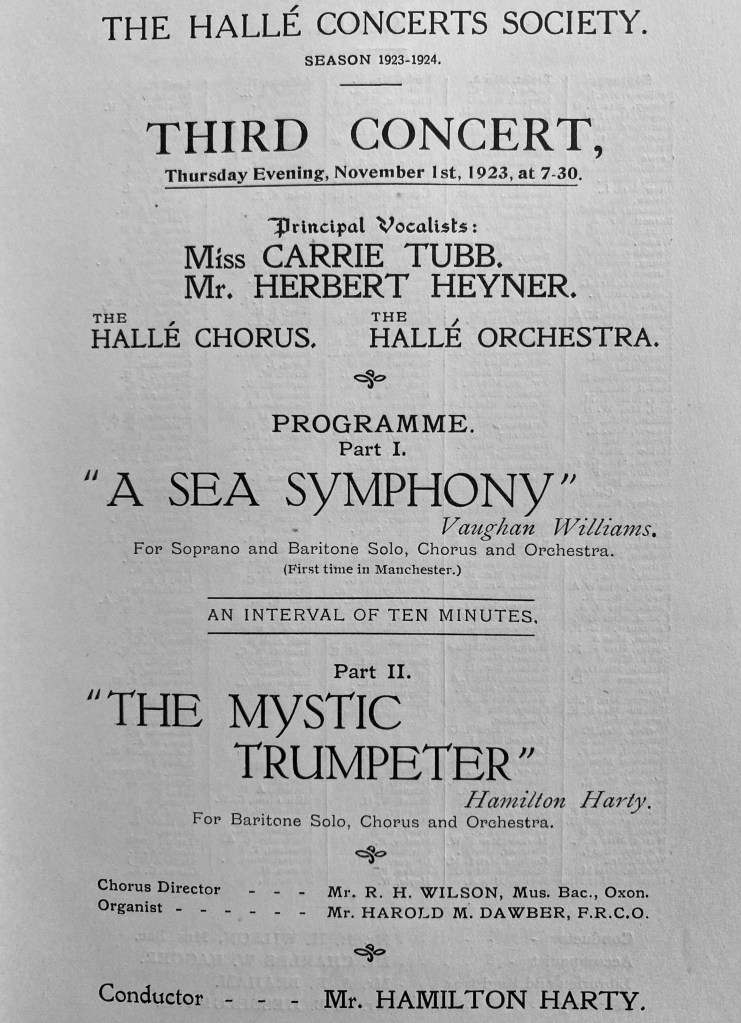

It may have been this very ‘newness’ that caused problems for the Hallé when it came to programming Vaughan Williams’ works during this period. Michael Kennedy suggests that ‘the new wind sweeping through music in the South and which had produced Vaughan Williams’ Sea and London symphonies… was felt as only a whispering breeze in Manchester’, hinting that the then principal conductor Hamilton Harty was ‘hardly a man to pioneer’. Declan Plummer’s research suggests that there may also have been a reluctance on the part of the Manchester public ‘for certain modern composers like Vaughan Williams’, and this is borne out by the takings for some of Harty’s early Vaughan Williams performances, including the one where we first see the Hallé Choir perform Vaughan Williams. The Hallé premiere of the Wasps overture in March 1923 was the third lowest-attended concert of that season, and the first performance of the Sea Symphony the following November, paired with Harty’s own Whitman setting The Mystic Trumpeter, attracted the lowest receipts of any concert in the 1923/24 season.

It had taken 13 years from the first performance for the Hallé Choir to embrace the Sea Symphony, and as well as being financially unsuccessful, it also went down badly with the reviewer from the Manchester Guardian. Perversely, his view of the symphony was not that it was modern, but that it was not modern enough. Whilst recognising a degree of genius within Vaughan Williams, who was in attendance at the concert, his view was this was ‘hardly a mature example of that genius’. He would rather have heard ‘one of his later orchestral symphonies’, which he believed were ‘more difficult for the listener but… more unified in their content and more vital.

He was hardly less congratulatory in his description of the performance itself, which ‘had its brave moments of superb assurance and triumph’, but also ‘had its hair’s-breadth escapes and some moments of catastrophe and weakness’. The choir itself was not mentioned in person, so there is no indication as to whether those moments of weakness were orchestral or choral. Whichever they were, it was not a particularly auspicious introduction for the choir to the music of Vaughan Williams.

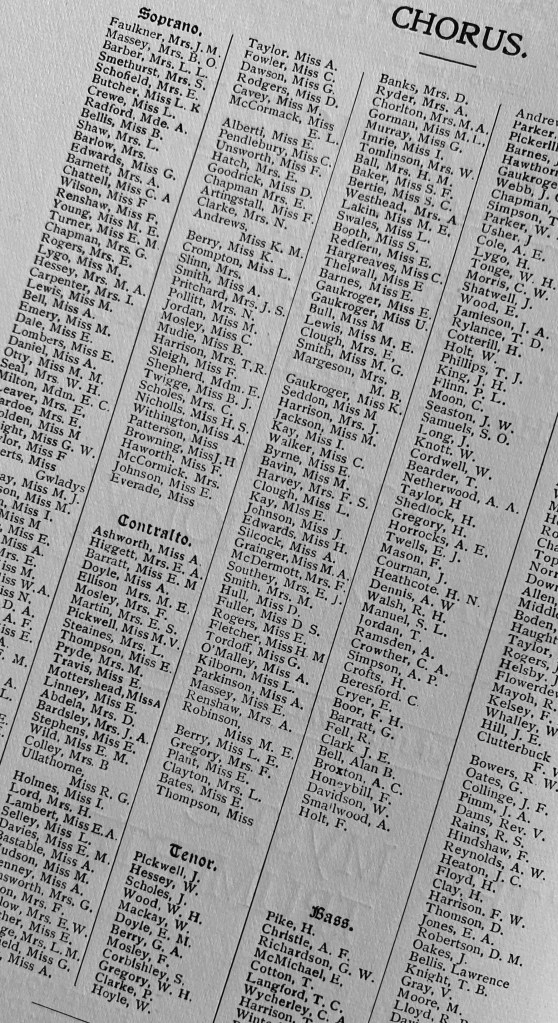

In terms of sheer numbers of choral singers, however, the concert must have been impressive. Under their long-serving choral director R.H. Wilson, no fewer than 368 singers are listed in the programme. Even allowing for the fact that this is probably a list of the total membership of the choir rather than a list of those singing in the concert, it is a mighty number, more than twice the total membership in 2022. The sound of the choir blasting out the opening words of the symphony – ‘Behold, the Sea Itself’ – must have shocked the Free Trade Hall audience in 1923, as it still has the capacity to do today in the Bridgewater Hall.

Whether it was because of the critical reception or the poor audience, the Hallé Choir was not to sing Sea Symphony, or any other Vaughan Williams work for that matter, for another 13 years. In the interim Vaughan Williams continued to produce fresh choral works and choirs in Manchester and the North continued to perform them, with the Manchester Vocal Society performing the Tudor-inspired Mass in G Minor in 1925 and the Five English Folksongs in 1930, the Leeds Festival Chorus reprising the Sea Symphony in 1925, this time with the Hallé Orchestra, and the Sale and District Musical Society performing his setting of the Magnificat in 1935. In 1936, the Huddersfield Choral Society, along with the Hallé Orchestra, gave the premiere of one of Vaughan Williams’ most substantial choral works since the Sea Symphony, his Dona Nobis Pacem, an impassioned plea for peace in the midst of the growing unrest of the early 1930s that also included more settings of words by Walt Whitman.

The Hallé Choir would not undertake its first performance of Dona Nobis Pacem until 1973, but at least in 1936 the Sea Symphony returned to the repertoire, conducted by no less an eminence than Sir Henry Wood. Granville Hill, who reviewed the concert for the Guardian, hinted at this long hiatus and consequent unfamiliarity by describing how ‘some chorus singers regarded some portions of the work as exotic growths whereas the whole thing is probably more truly English in character than any other music ever heard at the Hallé Concerts’. He lamented the apparent lack of enough combined choral and orchestral rehearsal, saying that in their absence the audience had to ‘trade on the alertness and the sporting instincts of our performers’! However, he was kinder in his descriptions of the ‘harmonious and finely blended’ choral singing in the concert itself, though admitting that ‘precision in the vocal entries, clear definition of all the short notes of florid passages, and a confident treatment of certain phrases that should be pounced on suddenly and cut off with equal abruptness were not always managed’.

All therefore was still not well in the relationship between Vaughan Williams’ music and the Hallé Choir, which was again evident in 1941 when at the height of the Second World War the choir performed the choral version of the serene Serenade to Music, written for Sir Henry Wood in 1938 to mark the 50th anniversary of his first performance. Granville Hill remarked on the ‘tentative choral expression’ resulting from an apparent lack of familiarity with the score.

The event that cemented the work of Vaughan Williams as an indispensable part of the Hallé Choir’s repertoire was undoubtedly the appointment of John Barbirolli as principal conductor of the Hallé Orchestra in 1943. Barbirolli and Vaughan Williams developed a deep friendship following a performance of the Sixth Symphony in Oxford in the early 1950s with which Vaughan Williams was particularly impressed. This soon led to Barbirolli programming all of his then existing symphonies, plus his Concerto for Oboe, to be performed in the 1951/52 Free Trade Hall season.

Via this cycle, and at the age of 80 Vaughan Williams established a working relationship with the Hallé Choir that was to last for the next five years until shortly before his death in 1958. One of the highlights of the 1951/52 symphony cycle was that the performance of the Sea Symphony was to be conducted by the composer himself, as indeed would a performance by the Sheffield Philharmonic Choir a few days later. Vaughan Williams was not renowned as the most meticulous of conductors, though he had conducted the amateur singers at the annual Leith Hill Festival since its foundation by his sister Margaret in 1905 and was much loved by the choirs at that event despite occasional fiery outbursts! However, Ursula Vaughan Williams, who became Vaughan Williams’ second wife after the death of Adeline following a long fight with illness, wrote in her biography of her husband, R.V.W., how ‘the prospect [of the Sea Symphony concerts] was not too alarming’ because the Hallé and Sheffield choirs had both been ‘admirably trained by Herbert Bardgett’ and the soloists at both concerts would be Isobel Baillie and Denis Dowling, ‘both old friends’.

In the event the Free Trade Hall concert was very well received by J.H. Elliot, who reviewed it for the Guardian, despite some ‘errors of balance and ensemble that might have been avoided under the direction of one who is so to say a conductor by habit’. Overall he felt that ‘chorus, orchestra and soloists – Miss Isobel Baillie and Mr Denis Dowling – gave a sufficiently vivid and poetic experience’. This was after all the Grand Old Man of English music, and Elliot talked of how ‘audience and performers alike rejoiced in the opportunity of paying generous homage to a great man.’

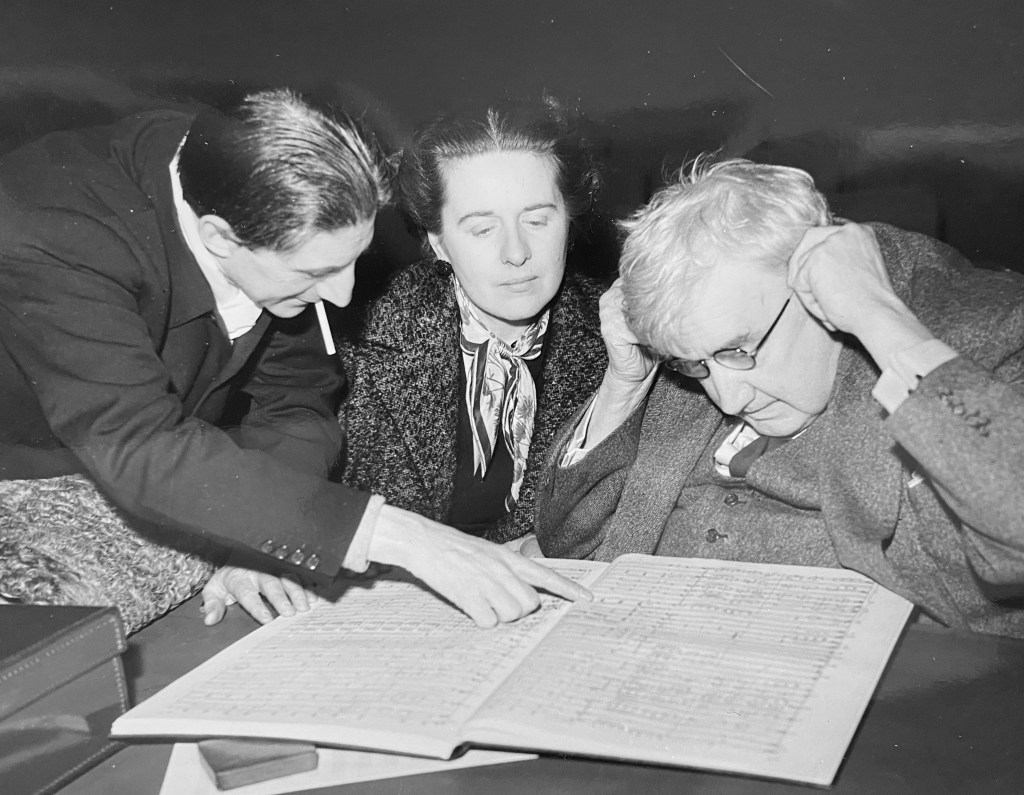

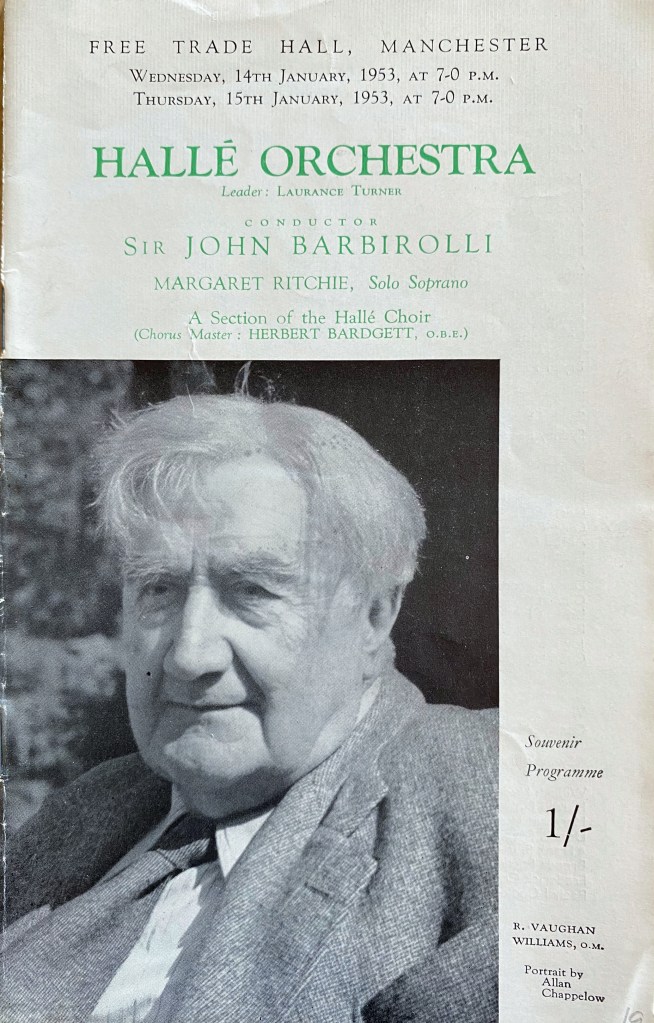

The big event the following season was however the first performance of Vaughan Williams’ seventh symphony, the Sinfonia Antartica, with its critical role for wordless female chorus, solo soprano and wind machine as they portray the desolate Antarctic wastes in the first and last movements of the symphony. The premiere was quite the event. Ursula Vaughan Williams describes Ralph being besieged by reporters and photographers, along the explorer’s son, the naturalist Peter Scott. Her description of the conclusion of the piece is particularly evocative:

By now we were beginning to know the symphony and something of the cold, desolation and strength of that remote world must have entered the experience of each one present, so that it was almost a release when the siren voice, the wind machine and the lower strings merged into silence. The silence lasted a moment before the applause began, and Ralph had to dash downstairs to take his call. He and John beamed at each other, Mabel Ritchie emerged from the hiding place dedicated to ‘voices off’, applause went on and on, and the symphony was safely launched

Ursula Vaughan Williams: R.V.W. – A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams, p. 317

The critical reviews reflected this sense of occasion. Eric Blom, writing in the Observer, called it ‘the veriest Vaughan Williams, not only because it is so entirely characteristic of him, but also because it shows that even now, at the age of eighty, he never stands still… Much of he music gives such a vivid impression of frostiness that sounds almost becomes transformed into temperature’. The reviewer for the Times marvelled at the sound world of the symphony: ‘A vibraphone is added to the percussion, a piano puts the edge on the chords of winds an strings, the organ has a solo, a wind machine provides a touch of icy realism, and, strangest of all, the ultimate desolation is portrayed by a female chorus and the solo voice of Miss Margaret Ritchie.’

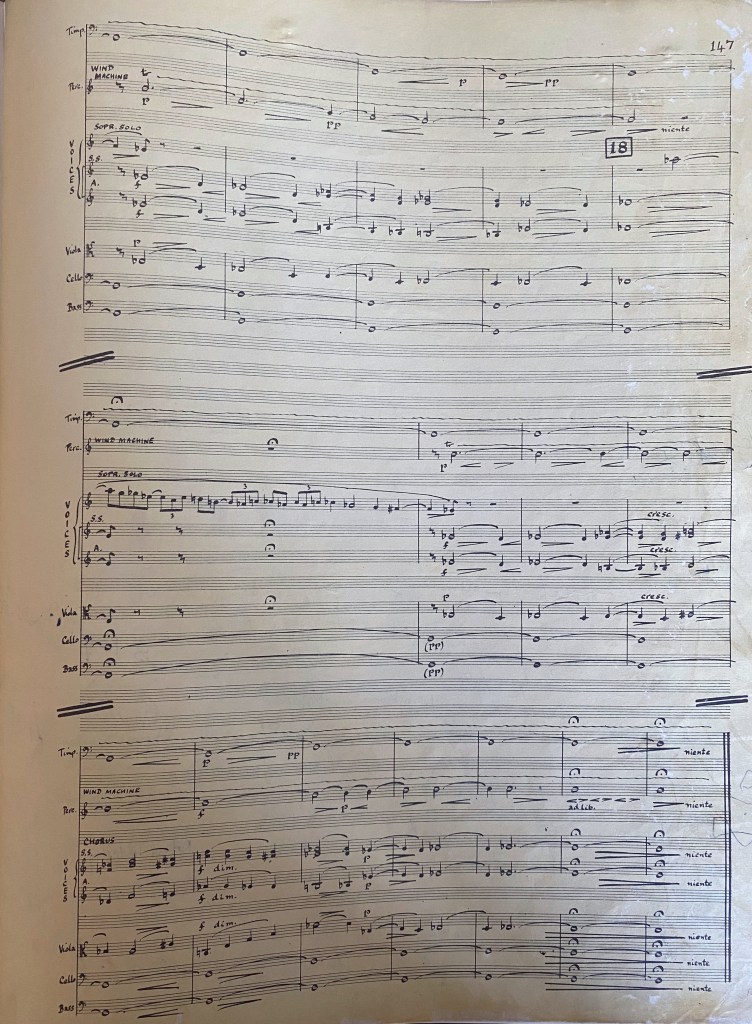

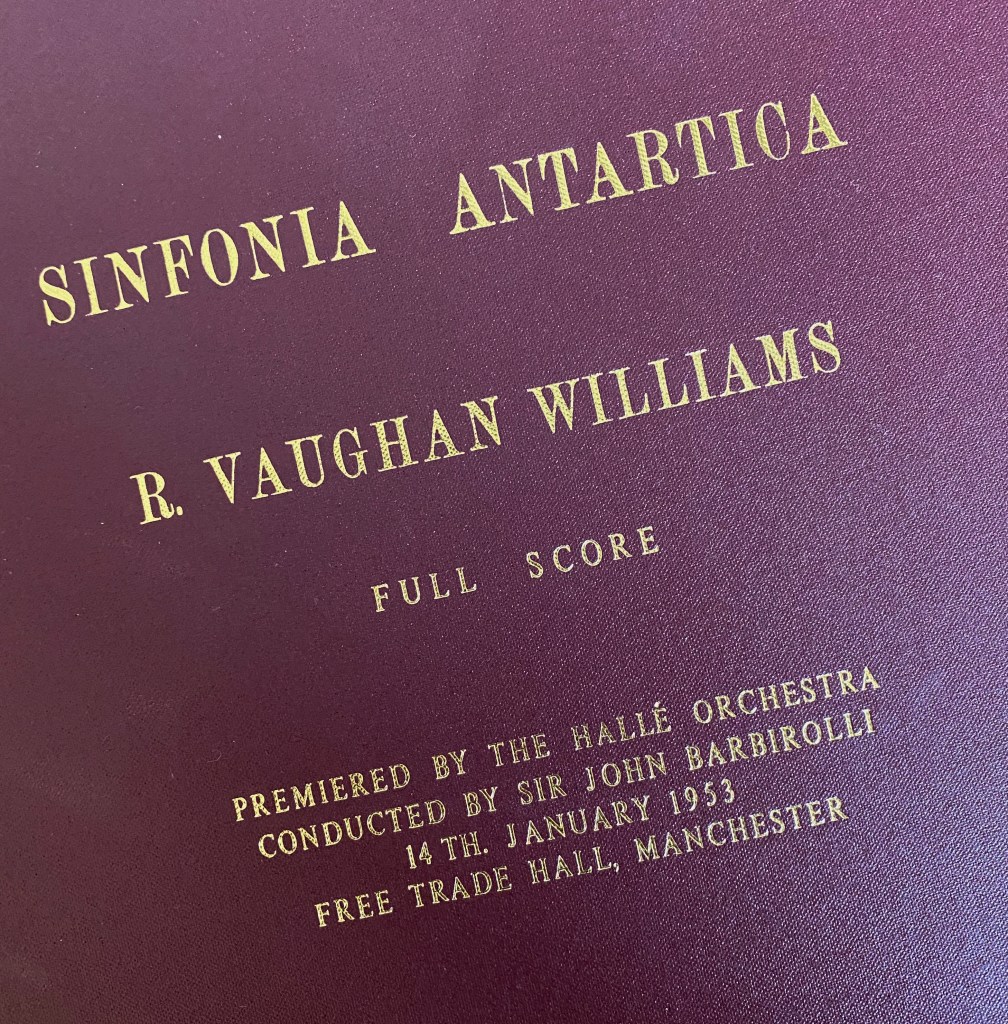

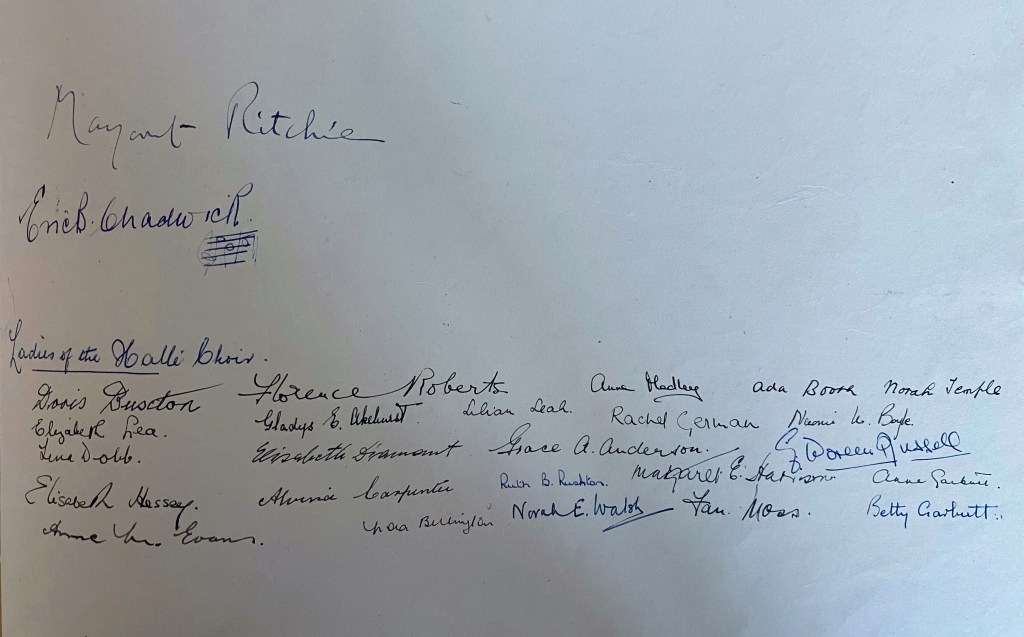

Though they sang off stage and it would appear they did not come onto the platform to take their applause, the sopranos and altos who sang in this premiere are remembered in a wonderfully special way. Whilst the manuscript score of the symphony was donated to the Royal Philharmonic Society, the performing score that was used by John Barbirolli on the day remained in Manchester and can be found in the Hallé Archives. What makes it special is that it has been signed by all those involved in the performance – the composer and conductor, Ursula Wood (as she was known at the time before her marriage to Ralph), all of the members of the orchestra, the soloist Margaret Ritchie, the choral director Eric Chadwick, and all of the sopranos and altos of the Hallé Choir who took part in the performance.

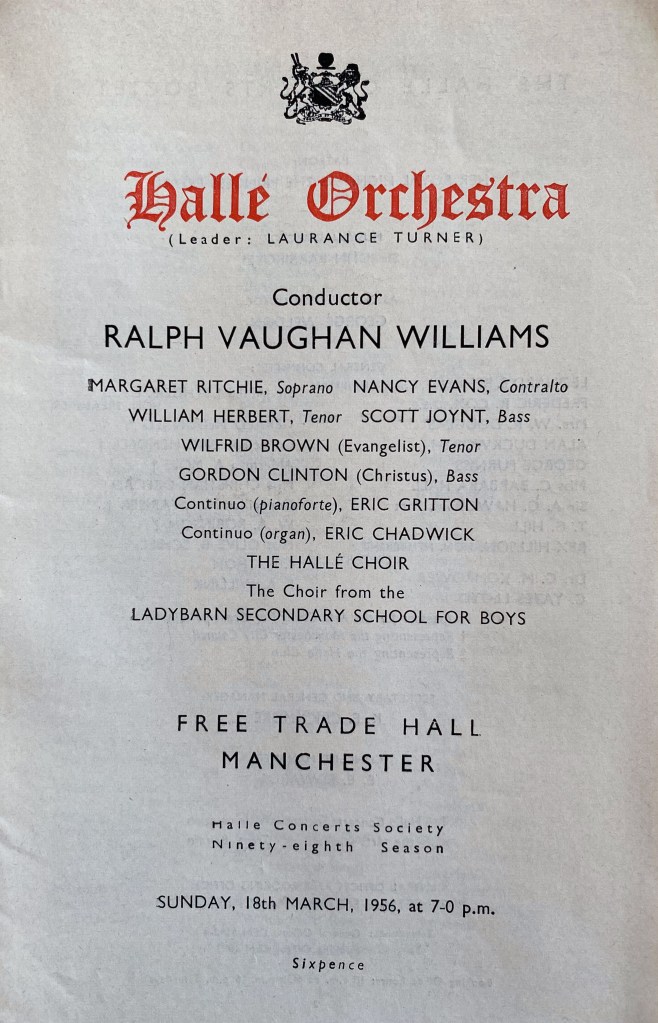

Vaughan Williams’ greatest musical hero was probably Johann Sebastian Bach, and a feature of the Leith Hill Festival concerts over the years had been the regular performances of the two great Bach passion settings, the St Matthew Passion and the St John Passion. It was therefore probably no surprise when Vaughan Williams was engaged, at the age of nearly 84, to conduct a performance of the St Matthew Passion with the Hallé Orchestra and Choir, Ladybarn School Choir, a stellar cast of soloists, and Vaughan Williams’ customary piano continuo. Here was music that Vaughan Williams had lived and breathed all his life, and this is reflected in Colin Mason’s review of the performance in the Guardian. As always with Vaughan Williams conducting there were technical issues – ‘the exciting effects were more in the conception than the performance’ – but ‘the chorus sang strongly, and Vaughan Williams held them together with the orchestra.’

Most moving to the reviewer were the chorales, in which in typically democratic manner Vaughan Williams frequently asked the audience to join. Mason describes two chorales in particular lighting up with ‘the most marvellous beauty and poignance’.

Once again, as with the Sinfonia Antartica and Sea Symphony performances, there was a real sense of occasion about the performance. Given the reception Mason suggested that a performance of this work could become an annual fixture, maybe in order to ‘give “Gerontius” its well-earned and much-needed rest’!

This solid link between Vaughan Williams and the Hallé was further reinforced by the gala concert given in the Free Trade Hall to celebrate his 85th birthday in October 1957. Though the Hallé Choir was not directly involved, the concert being made up of selections from Vaughan Williams orchestral repertoire, including his Eighth Symphony that had been premiered by Barbirolli in 1856, it started with a rendition of his setting of the Old 100th that involved boys from Chetham’s School. The hall was full for the concert, a contrast with Manchester’s previous attitude to the composer that was hinted at by Colin Mason reviewing the concert for the Guardian. He reported the person next to him saying ‘Forty years ago you could hardly get people to the hall for a work by Vaughan Williams’. Not so now, it would seem.

The immediate aftermath of Vaughan Williams’ death in August 1958 saw the Hallé Choir perform his Fantasia on Christmas Carols at the Hallé’s annual Christmas Concerts in 1958 and 1960 under George Weldon, and also, in November 1960 and with the same conductor, the first performance of Sea Symphony since the composer’s own reading almost ten years earlier. J.H. Elliot’s review harked back to that concert in his comment that ‘V.W.’s gifts did not embrace conspicuous skill with the baton’, but saw this time a ‘performance that yielded a generous measure of [the Sea Symphony’s] poetic force and musical beauty’. He praised the choir – ‘the considerable demands of the symphony were very well fulfilled’ – and gave special praise to the soloists, Heather Harper and John Cameron. He saw it as a ‘considerable adornment to the Hallé season’.

In the following decades Vaughan Williams’ choral works only occasionally appeared in Hallé concerts, one notable event being the Hallé Choir’s first performance in February 1973 with conductor Meredith Davies of Dona Nobis Pacem, nearly 40 years after its first performance by the Hallé Orchestra and Huddersfield Choral Society. It formed part of that season’s centenary tribute to the composer. Gerald Larner’s review in the Guardian heaped praise on the performance, seeing it as ‘the best possible combination of precise and dramatic attack with the soft-edged poetry of the English choral tradition’. The choir ‘seemed at ease amid the numerous rhythmic difficulties and, though once or twice upset by the strange modulations, they sang with a sense of knowing what the harmonies are about, or at least what their expressive intentions are’. This suggests a composer whose idiom the choir now understood, fifty years after their uncertain introduction to the Sea Symphony.

The next major event in the story of Vaughan Williams and the Hallé was the appointment of Mark Elder as principal conductor of the orchestra in 1999. Whilst Sir Mark is rightly praised for bringing Edward Elgar centre stage in the orchestra’s repertoire, particularly in his award-winning recordings of Elgar’s oratorios, he was also a champion both in performance and in recording of many other English composers of the 20th century, composers such as Delius, Holst, Bax and Ireland. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the gala concert held to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the orchestra in 2008, which featured four works that demonstrated Sir Mark’s commitment to the English repertoire, a new fanfare by Colin Matthews that opened the concert, Elgar’s In the South, a performance of Constant Lambert’s The Rio Grande that featured the Hallé Youth Choir, and finally Vaughan Williams’ Toward the Unknown Region, sung by the Hallé Choir, according to Tim Ashley writing in the Guardian, ‘with passion’.

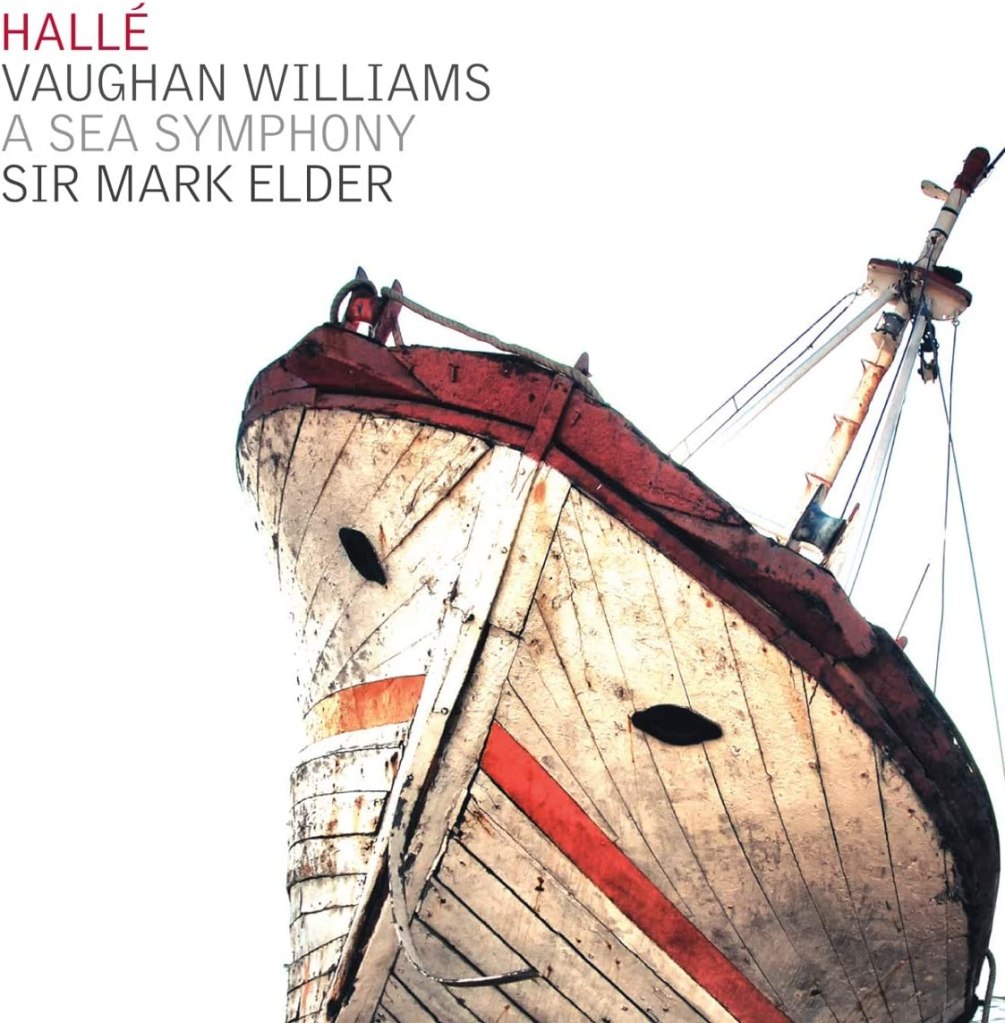

Two years later in 2010, Sir Mark began the process of recording a complete cycle of all nine Vaughan Williams symphonies. The choir’s first chance to contribute to this cycle came in 2014 when a performance of the Sea Symphony on March 29th and the rehearsals that preceded it were recorded for the CD that was released a year later in 2015. In the concert the choir and orchestra were joined by soloists Katherine Broderick and Roderick Williams, the Hallé Youth Choir, the Ad Solem choir from Manchester University and the Schola Cantorum of Oxford. The choir was trained by James Burton who had been brought in by Sir Mark early on in his tenure with the orchestra to both raise choral standards and expand the choral family with the creation of the Hallé Youth Choir and Hallé Children’s Choir. He had left the choir in 2009 to pursue other interests but had been brought back as a guest director for this project. I will say more about the choir’s recent history of choral directors in a later blog.

The concert and the subsequent recording received much praise from the critics. Tim Ashley, reviewing the concert itself in the Guardian, thought the choral singing ‘had tremendous nobility, weight and elation’. The recording was shortlisted for the orchestral category in the Gramophone Classical Music Awards for 2016, losing out to Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Given the five-star reviews it received this nomination was no real surprise. Andrew Achenbach in the Gramophone praised ‘the superbly honed choral and orchestral contribution’, and Robert Matthew-Walker in Classical Source the ‘exceptional quality’ of the combined choral forces. Geoffrey Norris in the Telegraph especially praised the final movement:

The long finale – a full half-hour – is exceptionally well modulated and shrewdly paced, achieving a fusion of flow and moving intensity in which orchestral and choral colour, together with the deep expressivity and dynamism of both the baritone and the soprano Katherine Broderick, combine to attain inspiring heights.

Geoffrey Norris – Daily Telegraph, August 30th 2015

The choir’s second contribution to the Vaughan Williams symphony cycle came about in January 2019, when the sopranos and altos gathered backstage with soprano Sophie Bevan to provide the wordless voices for a performance of Sinfonia Antartica, 62 years after that first performance in the Free Trade Hall. As an offstage chorus behind a partly closed door, the singers apparently had to sing very loudly to sound suitably quiet and ethereal! Owing partly to coronavirus pandemic, the recording of the performance was not finally released until the spring of 2022, but like the earlier recording it garnered much praise. Richard Fairman in the Financial Times found ‘the atmospheres of frozen landscapes uniquely chilling’. Terry Blain in Classical Music thought the Hallé’s playing mixed ‘grandeur and tragedy, with Sophie Bevan’s siren soprano and the voiceless chorus atmospherically integrated’.

This brings the story of Vaughan Williams and the Hallé Choir almost up to date. I will touch on the choir’s landmark performance of the oratorio Sancta Civitas at the Proms in 2015 in my next blog, which will look at the choir’s relationship over the years with the Proms. Mention should also be made of some memorable performances of Vaughan Williams Serenade to Music that occurred in 2019. In the first of these, the choir sang the choral version of the work as an encore following a performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, to celebrate the final performance by Lyn Fletcher as Leader of the orchestra. A few months later, the choir were in Valladolid as guests of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Castilla y León and their English conductor Andrew Gourlay, appearing in two concerts with the orchestra in which they performed the version of the Serenade for four soloists and choir, and which also included other English works such as The Planets by Holst and Vaughan Williams’ Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. The first of these Serenade performances, in a stifling concert hall, was enlivened a member of the bass section fainting at the quietest point of the piece, an event that the choir negotiated with their usual resolve! The concerts were enthusiastically received by a Spanish audience many of who were hearing these pieces for the first time.

And so to 2022 and the celebration of the 150th anniversary of Vaughan Williams’ birth. Vaughan Williams’ music has experienced many critical peaks and troughs over years, but particularly with works like the Tallis Fantasia, The Lark Ascending, and the Sea Symphony, his works have remained popular with the general listening popular, and there now seems to be a much greater appreciation of the visionary nature of his work and the sheer breadth of his musical achievement, from the lyrical beauty of The Lark Ascending and Serenade to Music to the naked anger of Symphony No. 4, both of which are combined in works such as Dona Nobis Pacem.

As I have shown above, it maybe took the Hallé Choir a little time to get to grips with the music and Vaughan Williams, but the choir’s early uncertainties with his music have led to an appreciation today that Vaughan Williams lies at the core of what the choir is all about, and indeed the Hallé Choir has done its bit to celebrate Vaughan Williams and his music in this his anniversary year in its contributions to the Hallé and BBC Philharmonic’s joint cycle of symphonies that took place in the first half of the year in the Bridgewater Hall. Firstly the choir joined forces with the BBC Philharmonic and veteran Vaughan Williams interpreter Sir Andrew Davis to perform Toward the Unknown Region. This was followed a few weeks later by a performance of the Sea Symphony, conducted by Sir Mark Elder, in which the choir were joined once again by the Hallé Youth Choir, along with soloists Roderick Williams and Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha. This concert again drew many favourable reviews. Rohan Shotton in Bachtrack wrote that the choirs’ sound ‘in the fortissimos of the first movement was overwhelming without ever compromising on diction or attention to the text’, and Robert Beale, writing on theartsdesk.com, felt Sir Mark ‘was able to draw remarkable effects from his choral singers’.

It would appear that Vaughan Williams’ reputation is safe with the Hallé and the Hallé Choir for the next 150 years!

References:

Alldritt, Keith, Vaughan Williams: Composer, Radical, Patriot – A Biography (London: Robert Hale, 2015).

Kennedy, Michael, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960).

Plummer, Declan, ‘Hamilton Harty’s Legacy with the Hallé Orchestra (1920-1930): a Reassessment’, Journal of the Society for Musicology in Ireland, 5 (2010), pp. 55-72.

Vaughan Williams, Ursula, RVW : A Biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams ([S.l.]: Oxford University Press, 1964).

plus the Hallé Archive, the Guardian and Observer Archive, and the various internet review sites quoted

Leave a reply to On Record – Part 4: The Mark Elder Years 2013 – 2023 – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply