We left the story of the birth of the Hallé Choir in 1858 just after the first choral performance at one of Charles Hallé’s newly-established ‘Grand Orchestral Concerts’ at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. I quoted the Manchester Guardian’s rather disparaging remarks about the choir. The Guardian were not alone in this regard, and the Manchester Times was equally scathing when its review landed a few days later:

If Mr Hallé had been as fortunate in his choral as in his instrumental forces, we might consider him a gentleman to be envied; but the choir, we should feel inclined to think, have not had the training of the band, nor the opportunity of familiar acquaintance with the exceptional style of music they were called upon to perform.

Manchester Times review, February 13th, 1858 (British Newspaper Archive)

Whether it was the effect of these less than effusive reviews of his choir, but Hallé soon set about improving the standard of the choir by adopting, consciously or not we will never know, the helpful suggestion of ‘Amateur’, in his letter to the Guardian that I quoted in the previous blog, that he should consider organising ‘a vocal corps qualified to support the high class of instrumentalists who compose his admirable orchestra’.

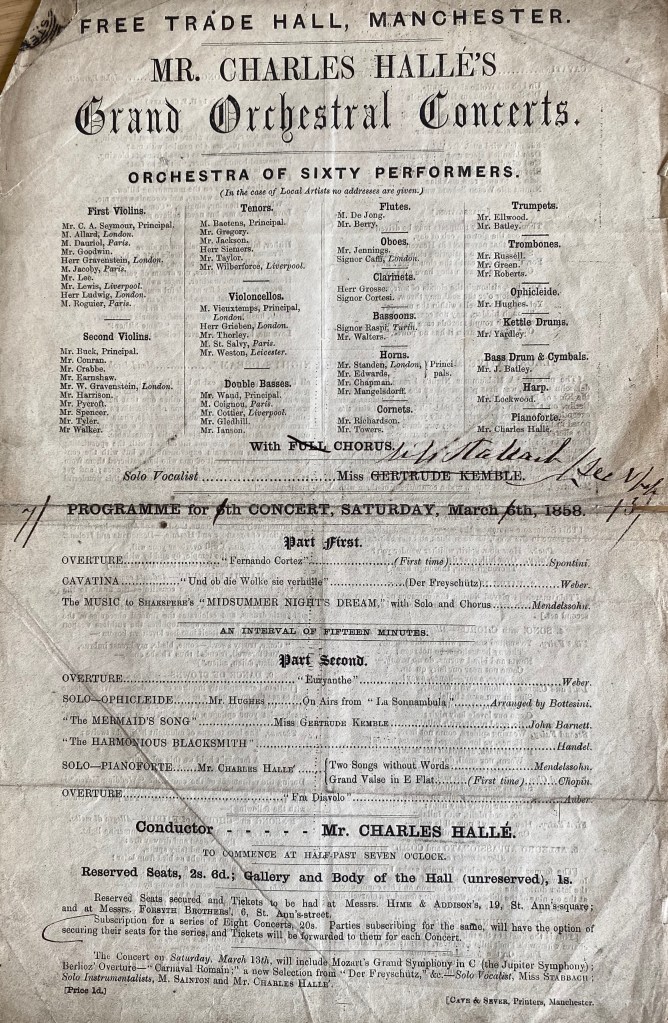

In the meantime more choral items appeared in the concerts of Hallé’s first season. On February 13th, a choir of sopranos and altos joined the orchestra in a performance of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream music along with an aria with chorus from Rossini’s La Carita, accompanying Miss Gertrude Kemble, much of which concert was repeated on March 6th. The Manchester Guardian commented favourably on Miss Kemble, but made no comment on the quality of the choral singing, other than that they were a ‘compact chorus’.

In the background, things were beginning to happen. The demise of the Hargreaves Choral Society and the fracturing of the choir that Hallé had assembled for the Art Exhibition concerts in 1857 had led to a situation where, as Robert Beale quotes from a Manchester Guardian review published on March 6th 1858 of a concert by the visiting Bradford Choral Society, ‘‘our choral singers are so scattered and broken up and the prestige that once attached to Manchester in reference to a vocal chorus is in danger of passing away.’ The reviewer goes on to qualify that this will happen ‘unless the attempt now being made by Mr Hallé to reunite the various smaller choral bodies in one comprehensive society should prove successful.’

Beale sheds light on what the reviewer was talking about here. Word had got around that Hallé was endeavouring to form a new choir that would unite Manchester’s best choral singers, and to the end a meeting was held in Manchester Town Hall on March 17th to provide more details on what would be known as the ‘Manchester Choral Society’. This new society would perform a series of six ‘dress concerts’ in the Free Trade Hall, conducted by Hallé, that would be available to subscribers at a cost of one guinea. As Hallé told the meeting that the choir would consist of around 200 voices and would ‘mainly consist of amateurs possessing the necessary musical qualifications,’ and that it would ‘be superior to anything we have had before in Manchester’.

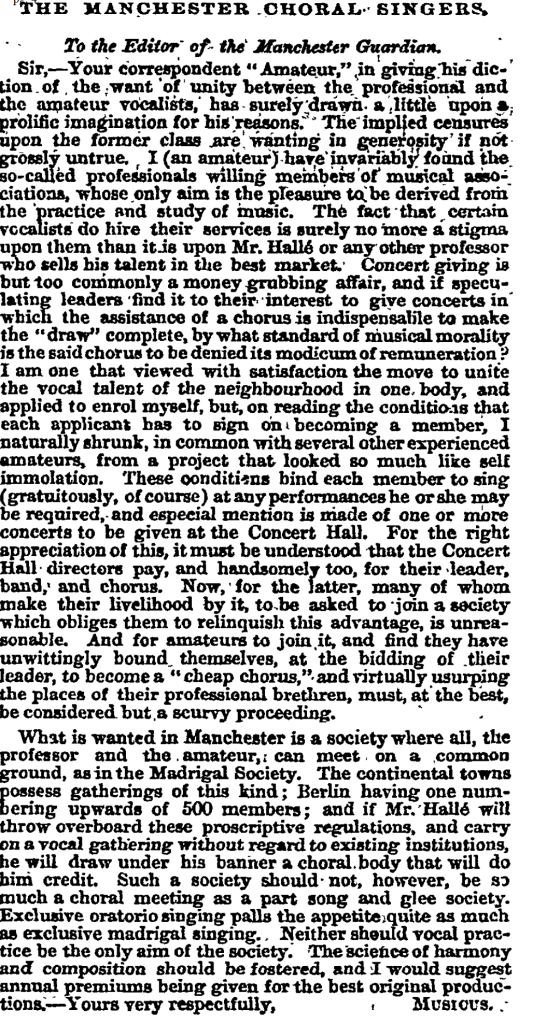

So far, so good, one might imagine, but the proposals incited a wave of opposition from the type of professional choral singer that had been the mainstay of the Hargreaves Choral Society. A letter to the Guardian objected that in making the proposed choir open only to amateurs, Hallé was restricting membership to ‘those who are of the highest class’, the implication being that this would have been the class of person most able to afford to sing without being paid. The immediate response of the professionals was the announcement of the setting up of a rival choir, made up entirely of professional singers and led by a Mr Banks, that would be called the Lancashire Choral Society, though this name was soon amended to the Manchester Vocal Union.

Hallé was obliging his singers to attend all rehearsals and appear in performances as required, and the fact that some professional singers were known to have signed up to these conditions as ‘honorary amateur members’ caused further resentment that those who made a living from singing in such concerts should join a society that forced them to relinquish any such remuneration. Another letter to the Guardian, though written by a professed ‘amateur’, complained that it would be ‘unreasonable’ for professional singers to relinquish the advantage of making their livelihood from singing and complained that ‘for amateurs to join it, and find they have unwittingly bound themselves, at the bidding of their leader, to become a “cheap chorus”, and virtually usurping the places of their professional brethren, must, at the best, be considered but a scurvy proceeding’.

Following further pressure, the term ‘honorary amateur’ was withdrawn and at a further meeting on April 12th that formally constituted the choir it was noted that though over 300 amateurs had applied to join the chorus it was also intended ‘to secure the services of the most efficient of the professional chorus singers of this locality’. Therefore, Hallé from the very beginnings of the Manchester Choral Society made payments to some of the chorus members. Indeed he formally advertised for professional singers who wanted an ‘engagement’ with the chorus to formally apply to him. The choir thus became a mixture of amateurs and, in the words of the society’s secretary, ‘competent professionals’.

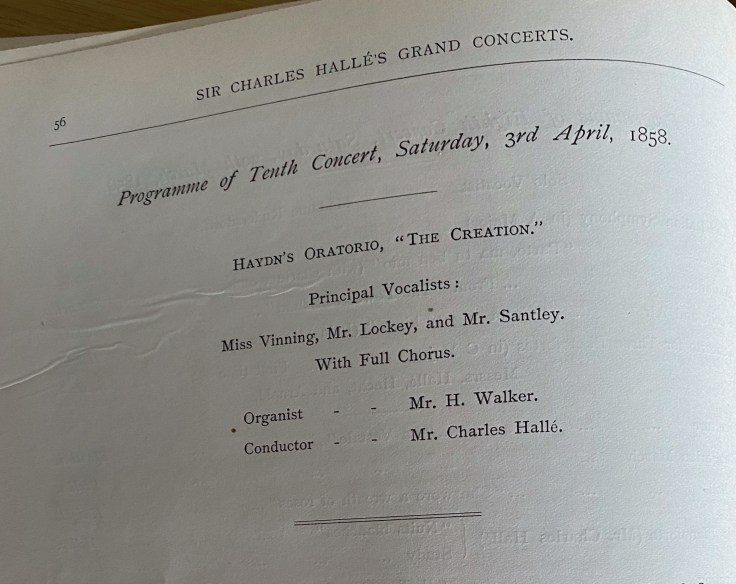

To return to the music of Hallé’s first season, the major choral event of the first season was the performance of Haydn’s Creation on April 3rd, the first time one of the works that had become a mainstay of choral society repertoire appeared in one of Hallé’s concerts. Sadly, the Hallé Archives no longer have a copy of the programme for this concert – it only exists as a page in a book recording all of the early concerts. What was described as a ‘Full Chorus’ joined Miss Vinning, Mr Lockey and Mr Santley in a performance that received much more fulsome praise than the Choral Fantasia a couple of months earlier. The Manchester Guardian praised it thus:

With Mr. Hallé’s superb orchestra, a carefully selected chorus of 140 to 150 (not paper singers, be it observed, but real flesh and blood vocalists), making thus, with the band of 60, a total strength of 200 and upwards; and Miss Louisa Vinning, Mr. Lockey, and Mr. Santley as principals, the production of Haydn’s great work could not fail to be successful. Perhaps 40 to 50 more voices might, in some of the choruses, have been desirable, in order to balance so powerful a mass of stringed and wind instruments; but upon the whole, the chorus was satisfactory. Neither precision, correct intonation, nor light and shade, though it is in these latter elements that there exists the greatest room for improvement, were wanting.

Manchester Guardian Review, April 5th 1858 (Guardian Archives)

Whilst this performance took place after the formal announcement of Hallé’s Manchester Choral Society, it is not clear to what extent the choir was utilising those who had applied to join the society. However, what does seem clear from the Guardian review is that the chorus had been significantly bolstered since their lacklustre Beethoven performance back in February.

The actual status of the chorus at this stage is therefore unclear, as is shown by the various ways in which the chorus was described in programmes during the early years of the orchestral concerts, which were often restricted to describing just the quantity of singers, rather than their actual provenance. In tandem with this in these early days, Manchester Choral Society maintained a parallel existence, with its first official performance being another performance of Haydn’s Creation in October 1858 as part of their first season of subscription concerts. Though conducted by Charles Hallé and presumably using the same musicians that he used, this concert is not listed in the Hallé Archive as an official Hallé concert, so at this point in time there was very much a distinction between the two.

The reviewer in the Guardian noted that the bulk of the singers for this performance were ‘carefully-selected’ amateurs assisted by ‘the most experienced of our [presumably professional] choral singers’, and wondered if the effect of this mixture would, mixing his linguistic references, be equivalent to an ‘omnium gatherum selection of soi-distant professionals’. His wonder did not last long – he found that ‘the choruses of the oratorio were gone through in the most satisfactory manner; no point was missed – all were up to their work, and all seemed animated by a desire to do justice to the noble work entrusted to their charge’.

The rivalry with the Manchester Vocal Union continued up to this point. The Vocal Union held its first concert month earlier on September 5th, a performance of Handel’s Israel in Egypt with a chorus of ‘upwards of 200 professionals’, but it would appear that the venture was not a success and by December the choir was being referred to in a notice in the Manchester Guardian as the ‘late Manchester Vocal Union’.

So, as he entered his second season of Grand Orchestral Concerts, Hallé had the singers of the newly-formed Manchester Choral Society to use as a resource along with the singers from the various choirs he had called upon in the past. The first choral concert of the new season was on September 25th 1858, when amongst various instrumental items a ‘Full Chorus’ reprised Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia, again conducted by Hallé from the piano, and also performed two glees by Spofforth and Webbe and the Market Chorus from Auber’s opera Masaniello. A glee was a variety of part song, usually sung by male voices, that was popular time. Many societies formed whose purpose was the singing of glees. Indeed the notice referenced above that referrred to the demise of the Manchester Vocal Union announced that many of its members had joined the new ‘Manchester Glee and Choral Union’. A brief review in the Manchester Guardian on September 30th called the choir ‘a well-selected chorus of professional singers, numbering 90 to 100’, indicating maybe that Hallé was determined the performance should improve on the previous season’s, but there is no mention yet of any link with the Manchester Choral Society. The review states that Hallé was ‘well supported by the band and the chorus’.

The fifth concert of the new season, again featuring a ‘Full Chorus’, was a similar miscellany, featuring this time the Fishermen’s Chorus from Masaniello along with excerpts from Weber’s Preciosa and a madrigal by Festa. The Guardian again spoke of a ‘well-selected chorus’ being engaged to sing alongside the soloist Miss Armstrong, and described their performance of the excerpts from Preciosa as being ‘very charmingly given’.

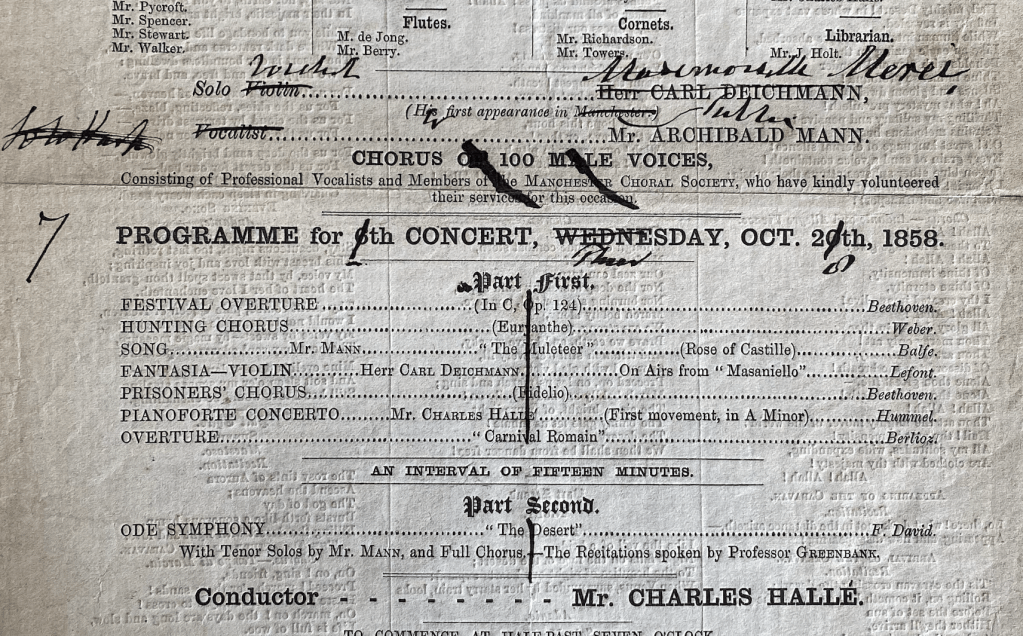

For the sixth concert of the season we see a change in the way the chorus is described. A chorus of 100 male voices was engaged which was described in the programme as ‘consisting of Professional Vocalists and Members of the MANCHESTER CHORAL SOCIETY, who have kindly volunteered their services for this evening’, the suggestion being that the Choral Society members were not being paid. In the first half of the concert the choir sang the Hunting Chorus from Weber’s Euryanthe and, for the first time, the Prisoners’ Chorus from Beethoven’s only opera Fidelio. The second half of the concert was taken up with a real historical novelty, the so-called ‘Ode Symphony’ Le Désert by the French composer Félicien David. Composed in 1844 following a trip to the Holy Land by the composer, it is neglected now, but was championed at the time by the likes of Hector Berlioz. It was set for unusual forces – tenor solo, male chorus, orchestra and speaker (for this performance ‘Professor Greenbank’). The Guardian reviewer was of no doubt that ‘David’s work is one of genius’, but although he felt the tenor soloist Archibald Mann and Professor Greenback both performed well, he made no mention of the quality of the chorus, but did hope that ‘Mr Hallé will give the public another opportunity of hearing the music of “The Desert”‘.

Two further concerts featuring miscellaneous opera choruses sung this time by a ‘Powerful Chorus’ were followed on January 26th, 1859 by a concert to celebrate the 103rd anniversary of the birth of Mozart the following day, which featured a ‘Full Chorus’ singing a chorus from Idomeneo in the first half and two choruses from The Magic Flute amongst a selection of solo arias from that opera in the second half. Interestingly the opera is named as ‘Zauberflöte‘, and yet the choruses and arias are listed in Italian rather than the German in which the opera was originally written.

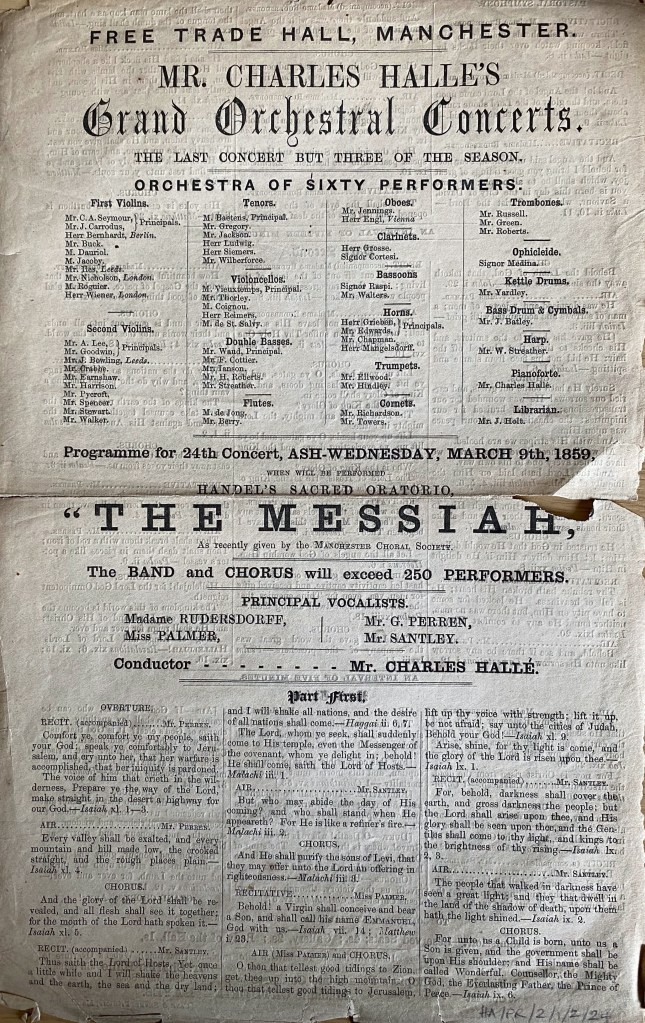

The choral highlight of this second season, though, was undoubtedly the first ever performance of, as the programme described it, ‘HANDEL’S SACRED ORATORIO “THE MESSIAH”, as recently given by the Manchester Choral Society’. Note the reference to the Manchester Choral Society who had performed Messiah twice within their first season of subscription concerts, the second performance, according to the Manchester Guardian, being an extra performance ‘for the benefit of the working classes’ which attracted an audience of ‘more than 4,000’. The Guardian’s review of this third performance, which took place on March 9th, 1858 – Ash Wednesday – states that although the lineup of soloists had changed since the Society’s performances, it was performed ‘with the same band and chorus’, suggesting that a process was beginning where the Manchester Choral Society would become synonymous with Hallé’s Grand Orchestral Concerts. The forces were massive, the programme stating that ‘the Band and Chorus will exceed 250 performers’. In passing, note the use of the definite article in the naming of the work in the programme, something that would be frowned upon by purists today! The makeup of the orchestra would also alarm modern purists, including as it did all the woodwind and brass instruments, harp and piano. The brass instruments included an ophicleide, a large brass instrument invented in 1817 that was popular throughout the century, appearing regularly in Hallé’s orchestra before being succeeded by the tuba.

The programme listed all of the words of the oratorio, indicating that it was performed uncut, a practice that the Hallé Choir follows only occasionally today. It is no surprise therefore that the Guardian reports that ‘the concert terminated about eleven o’clock’! The paper compared the performance favourably to the previous Choral Society concert:

The audience last night was a very large one, quite as much so as at the performance for the working classes, while the performance itself was in nowise inferior. The band and chorus were quite up to the mark, every chorus being sustained with precision and effect, especially the magnificent “Hallelujah,” “For unto us a child is born,” and “Worthy is the Lamb.”

Manchester Guardian review, March 10th, 1859 (Guardian Archives)

At the beginning of the 1859/60 season the pattern appeared to be set for the choral elements of Charles Hallé’s concerts, with a mixture of amateur and professional singers and frequent use of the forces of the Manchester Choral Society. What is noticeable through this new season is a rise in the number of performers. A reprise of excerpts from The Magic Flute in November (this time definitely in English) advertised a ‘Band and Chorus of upwards of 200 performers’, and the same forces appeared in excerpts from Beethoven’s Fidelio (also in English) a month later. However, by January’s performance of Gluck’s Iphigenie in Tauris, repeated a month later, this number had risen to 250, and by time of the February 22nd performance of Messiah to 300, 50 more than the number advertised for the first performance of the work a year earlier.

A week later, a performance of choruses from Mendelssohn and Haydn advertised a ‘Powerful Chorus consisting members of Manchester Choral Society’, and the first performance of Mendelssohn’s Elijah in April boasted the same forces as Messiah. The season ended with a benefit concert for orchestra in which various choruses for which the programme stated the ‘Chorus will consist of Professionals and members of Manchester Choral Society, who have kindly offered their services’.

The strong dependence of both the Grand Orchestral Concerts and the Manchester Choral Society on Hallé as organiser, programmer, performer and conductor is evidenced by the fact that the following season, when Hallé’s commitments in London took him away from Manchester, he only conducted one, purely orchestral, concert at the Free Trade Hall. When normal service resumed the following season, 1861/62, there were changes.

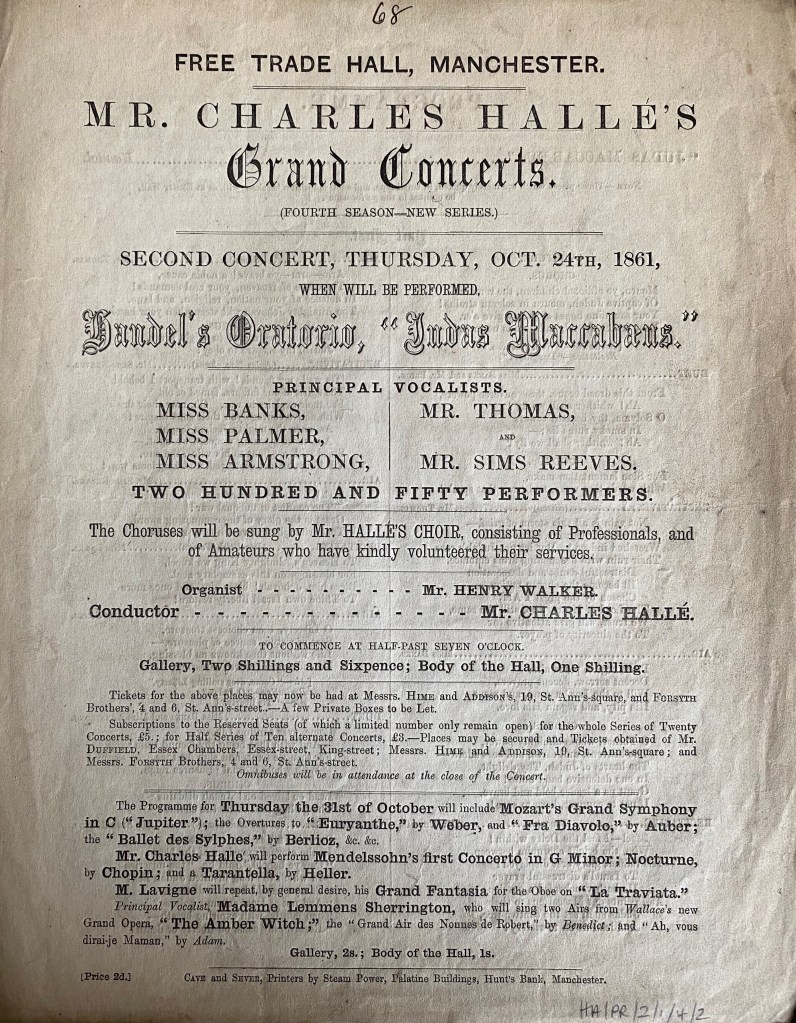

Firstly, the concerts were now simply called ‘Mr. Charles Hallé’s Grand Concerts’. Secondly, the Manchester Choral Society was no more. A preview of the season published in the Manchester Guardian on October 2nd, 1861 stated that ‘of the 20 concerts to be given, eight will be choral concerts, thus supplying the gap occasioned by the dissolution of the Manchester Choral Society’. The society had managed to put on its own concerts, conducted by Hallé, through the 1860/61 season, including a well-received Messiah in December 1860 and a performance of Cherubini’s Requiem in March 1861, but now Hallé had decided to subsume the choir formally into the structure of his Grand Concerts.

As a result, for the second concert of the season, a performance of Handel’s Judas Maccabeus, there was the following grand announcement in the programme:

The Choruses will be sung by Mr. HALLÉ’S CHOIR, consisting of Professionals, and of Amateurs who have kindly volunteered their services

Programme for Mr Charles Hallé’s Grand Concert of October 24th, 1861

The review in the Manchester Guardian, suggested that this was an official designation, a collection of singers who had ‘voluntarily enrolled themselves under Mr. Hallé’s banner, the united body taking the designation “Mr. Hallé’s choir”‘. This was therefore the first point at which the chorus accompanying Hallé’s orchestra could truly be called the ‘Hallé Choir’. The reviewer was impressed by the ability of the newly united chorus, stating that the choruses of the oratorio were ‘of a character to try the best-trained chorus’, but that the choir showed ‘not only accurate knowledge of what was wanted, but the power to accomplish it’.

For the rest of the season, which included two performances of Messiah, and Mendelssohn’s St Paul, the combined band and chorus were consistently described as being 250-strong, which suggests a stability in membership had been achieved.

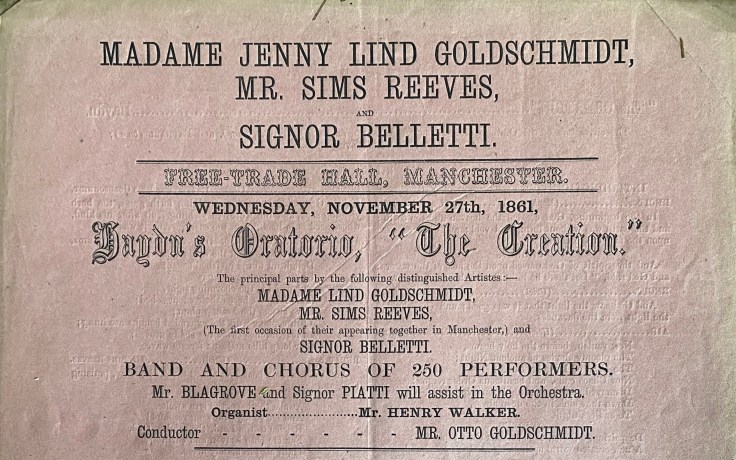

The highlight of the season, though, was undoubtedly the performance in November, 1861 of Haydn’s Creation which featured the renowned soprano Jenny Lind, known throughout the world as the ‘Swedish Nightingale’. Lind had worked with Hallé on occasions before, but this was her first performance with Hallé’s orchestra and came after a brief retirement from public life to care for her young family with her husband, the pianist and conductor Otto Goldschmidt. Interestingly, Goldschmidt rather than Hallé performed the conducting duties, the first time the chorus had sung under someone other than Hallé. Such was Lind’s fame that practically all of the review in the Manchester Guardian was devoted to discussion of her vocal talents, on which the reviewer was ambivalent (her voice ‘is not remarkable for purity of tone nor for evenness’, but she has ‘the old Scandinavian force of imagination and depth and intensity of feeling’), her charitable works (she had donated £2,700 to the Manchester Infirmary), and her performance on the day (‘an exceedingly fine one’ though ‘the music is not of a character to exhibit Madame Goldschmidt’s powers to the greatest advantage’).

The choir got brief praise at the end of the review – once again ‘they were fully up to mark’ – though the reviewer was rather more exercised by the distribution of the choir, complaining that ‘both they and the band materially interfere with each other’, and suggesting that ‘if a better distribution of them could be made, so as to raise them up one above another, a much greater effect could be produced’. Arguments about choir layout and balance between orchestra and choir are nothing new!

The choir entered the 1862/63 in fine fettle, and obviously augmented as all of the concerts for this season and the following season advertised a ‘Band and Chorus of nearly 300 performers’. This was a quiet season though, with a concert in November celebrating the music that had been played at the Art Exhibition five years previously, one in December including choruses by Rossini and Auber and another in December featuring a further performance of Messiah, and a concert in March 1863 that included the Choral Fantasia and choruses by Gluck, Beethoven and Mendelssohn.

The following season, however, saw a run of concerts that would test the best modern symphony chorus. Hallé was obviously keen to let his choir off the leash and show what they could do. I will end this review of the early days of the Hallé Choir by simply listing the astounding list of works that were performed in a brief period during the 1863/64 season, which included the first ever Hallé Choir performance of the Ode to Joy from Beethoven’s 9th symphony. For the next blog I will leap forward in time and look at the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams, the 150th anniversary of whose birth is being celebrated in 2022, and the history of his association with the Hallé Orchestra, and specifically with the Hallé Choir.

| Date | Composer | Work |

| November 5th | Handel | Judas Maccabeus |

| November 19th | Handel Beethoven | L’Allegro il Penseroso ed il Moderato Part 1 (with Jenny Lind) Choral Fantasia |

| November 20th | Mendelssohn | Elijah |

| December 3rd | Haydn | Creation |

| December 24th | Handel | Messiah |

| January 7th | Handel | Samson |

| January 28th | Beethoven Meyerbeer | Symphony No. 9 ‘Choral‘ Choruses |

| February 25th | Cherubini Weber Gluck Beethoven Gounod | Choruses (including accompaniment by the Military Band of the 49th Regiment) |

| March 3rd | Mendelssohn Rossini | Symphony No. 2 ‘Lobgesang’ Stabat Mater |

Sources

Beale, Robert, Charles Hallé: A Musical Life (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008).

British Newspaper Archive

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Hallé Archives, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester

Hallé, Charles, Life and Letters of Sir Charles Halle (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1896).

Johnson, Rachel M., ‘Musical networks in early Victorian Manchester’ (Thesis (Ph.D.), Manchester Metropolitan University, 2020) <http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/627596/>.

Kennedy, Michael, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960).

Leave a reply to The Hallé Choir Through The Years – An Exhibition at Hallé St Peters – The Hallé Choir History Blog Cancel reply