Introduction

In my last post I told the story of Margaret Hudson, who through her long life devoted herself in equal part to the education of children and the entertainment of others through music. Importantly for the overall story of the Hallé Choir she also sang several times in the semi-chorus for choir performances of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius. In this post I will continue my series about notable semi-chorus singers with the story of Alfred Ernest Houghey, also known, as you will see, as Ernest Howie. He was born in Liverpool in the same year as Margaret, but his life followed a very different trajectory to hers, ending over 5,000 miles from his birthplace in the sunshine of California. Though his connection with the Hallé Choir ended when he was 30 it is worth telling his story in full not least because it encompasses many of the key social and political developments of the 20th century.

In writing this blog I have been indebted to his great-granddaughter Kristene Vaughn who has provided me with some key information about his early musical career as well as some remarkable photos.

Alfred Ernest Houghey: Born in Liverpool in 1881, Died in Campbell, California in 1955

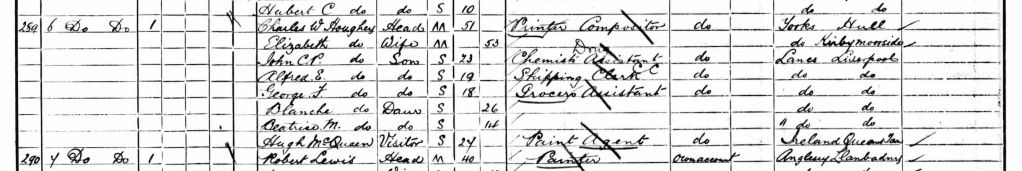

Alfred Ernest Houghey was born in West Derby, Liverpool to his Yorkshire born father and mother Charles and Elizabeth. Judging by most future references to him and the name he chose for himself for his singing career, I am happy to assume that he was generally known by his second name, Ernest, so I will call him that from hereon in. He had two brothers, an elder brother John and a younger brother George, and two sisters, an elder sister Blanche and a younger sister Beatrice. The 1901 census sees the family living in Silverdale Terrace, Wavertree. It shows Charles working as a compositor, arranging the type on a printing machine, presumably for one of the Liverpool newspapers, and Ernest (Alfred E) working as a shipping clerk.

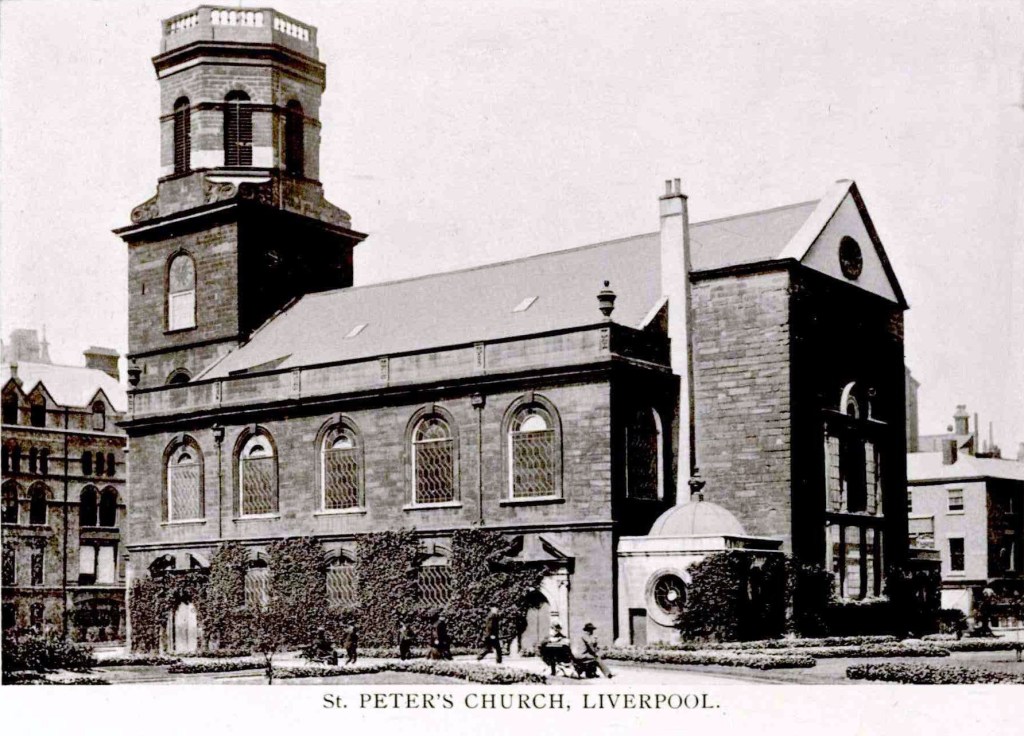

Ernest may have been working in an ordinary job in 1901 but a singing career that would blossom in the following years had begun at the age of 9. In 1880 the new Liverpool Church of England diocese was carved out of the old Chester diocese, following on from those of Blackburn and Manchester which had been created in similar fashion in 1847. St Peter’s Church in the middle of Liverpool, the church where Messiah was first heard in that city, was made the pro-cathedral for the diocese as the process began of finding a site for a new permanent cathedral. Work on building the new cathedral did not begin until 1904 so when the young Ernest Houghey was admitted into the Liverpool Cathedral Choir in 1890 he would have sung in St Peter’s. The church itself, though not the prettiest of buildings, is now sadly demolished though commemorated by the name of the street on which it sat, Church Street. Ernest sang in the cathedral choir until 1897 and for three of those years he was the leading boy treble, a sign that he was already developing a formidable voice.

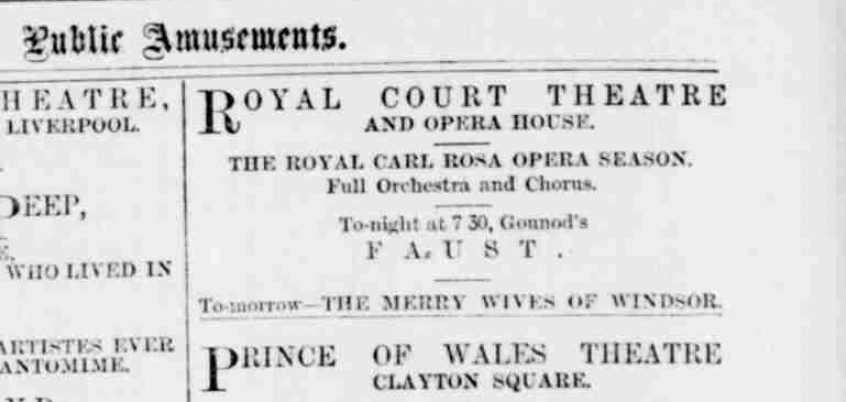

This is further evidenced by the fact that from 1894 to 1896 when his treble voice would have been at its strongest he also sang operatic boy soprano roles with the famous Carl Rosa Opera Company. This company had been founded in 1873 by the German impresario Carl Rosa and was specifically founded to present operas in English, like the present day English National Opera, and to bring them not just to London but to other major British cities. These included Liverpool, where they the company would appear at the Royal Court Theatre in Roe Street. This theatre had opened in 1881, but a previous incarnation of the theatre on the same site had featured a variety show, a copy of the poster for which was seen by John Lennon and became the inspiration for the Beatles song Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite. The Carl Rosa Company would regularly present series of operas there featuring some of the finest singers of the day. Whenever the need for a treble soloist arose one assumes they called on the young Ernest. Maybe he performed in the 1895 season advertised above.

After his voice broke Ernest fulfilled solo tenor duties at The Central Hall concerts at St Luke’s Church in Liverpool, which is best known today for having been bombed during the 1941 Liverpool blitz. The shell of what remained has been left as a memorial. Ernest obviously left an impression during his time there, as shown by this testimonial by G. Edwin Collier, the organist for the Central Hall concerts: ‘His unfailing courtesy, punctuality and conscientiousness, coupled with powers as a vocalist, will render him a valuable addition to any musical combination.’

From 1901 to 1903 he was also a member of the chorus and semi-chorus in the Liverpool Philharmonic Choir, and when he moved to Manchester during the course of 1903 it was therefore only natural that he should look to join the Hallé Choir, a choir he sung with until 1911. He thus became one of a select few to have sung for both the now Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir and the Hallé Choir (which includes myself, though my three appearances with the RLPC have only been as a guest!).

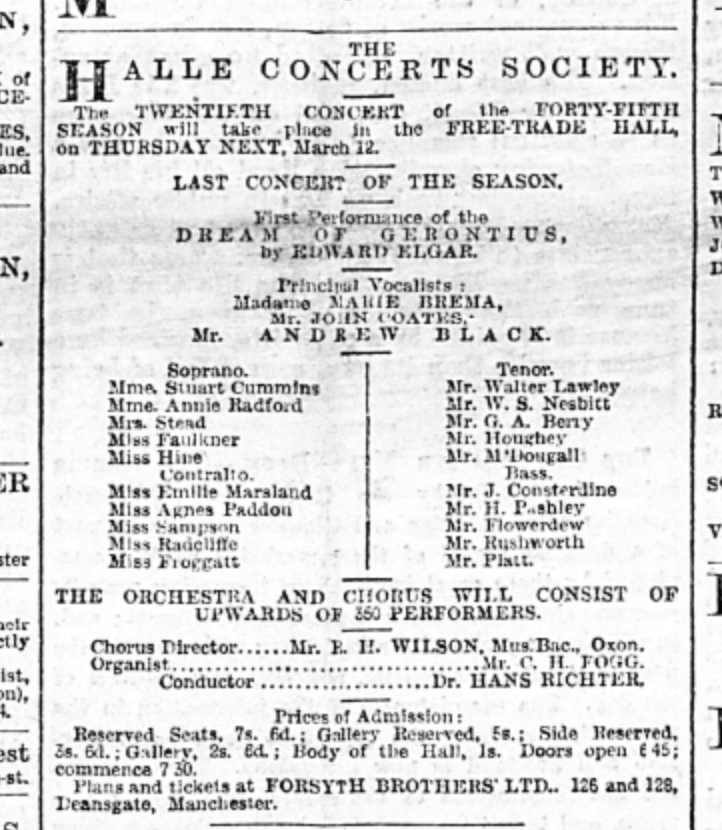

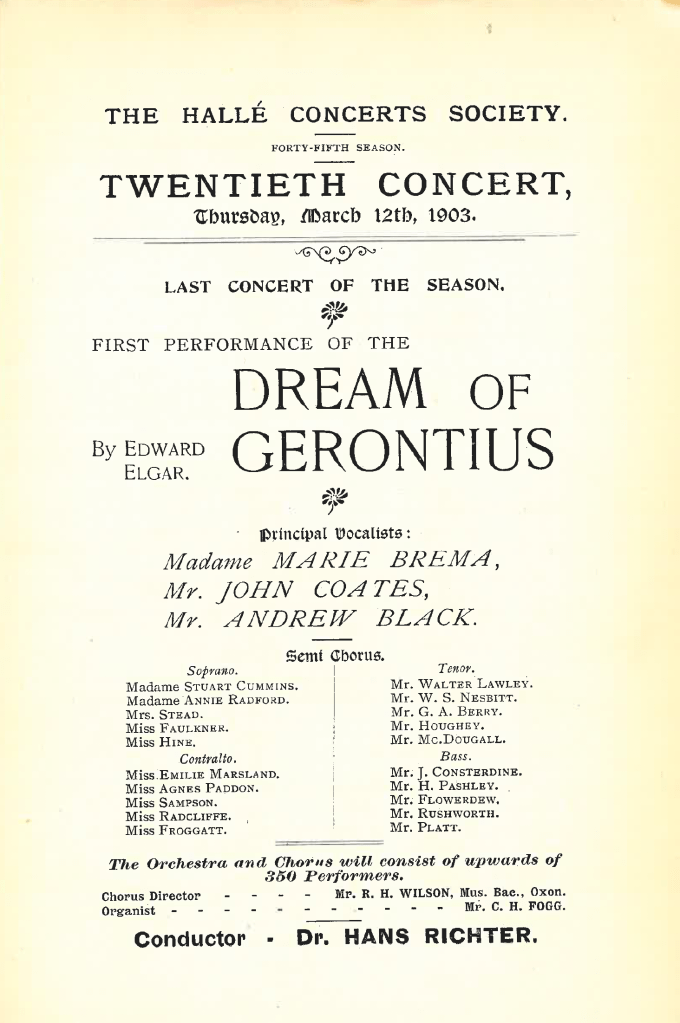

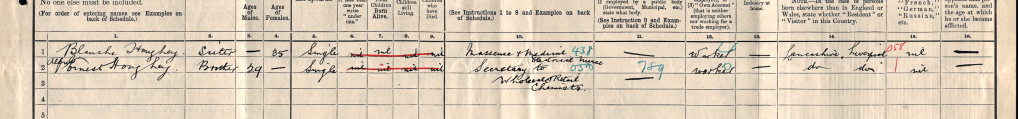

Whilst, as you will see, he later came to study singing in Manchester, judging by the dates I am guessing that he initially came to Manchester to work, maybe following in the footsteps of his older sister Blanche, with whom the 1911 census shows him living in Withington. Fortuitously, he arrived in Manchester just in time for the famous Manchester premiere of Elgar’s first great oratorio The Dream of Gerontius. I covered this concert extensively in a previous blog, but to recap briefly, the world premiere of this work in Birmingham three years earlier, conducted by the Hallé Orchestra’s principal conductor Hans Richter, had been something of a disaster. Its reputation began to grow as a result of performances Richter gave in Germany but it was this first Manchester performance, with the choir trained by the formidable R.H. Wilson, that truly sealed the work’s reputation in Britain. As you can see both from the advertisement in the Manchester City News and the title page of the concert’s programme, ‘Mr Houghey’ is named amongst the tenors of the semi-chorus.

The reviews of the concert seem to indicate that the semi-chorus of which Ernest was a member was an unqualified success. The Manchester Guardian reviewer gave fulsome praise to them:

…the difference between thorough success and ordinary half-success with this oratorio depends more on the semi-chorus than on any other point, and this is where the pre-eminence of last night’s rendering, among all yet given in this country, is most unquestionable… The voices blended well, and their combined tone was clearly distinguishable from the larger choir’s. At the notoriously dangerous points, such as the re-entry with the “Kyrie” after the invocation of “angels, martyrs, hermits, and holy virgins,” there was no hint of embarrassment, and they played their part as a slightly more delicate choral unit with absolute success in the litany and throughout the marvellous concluding chorus of the first part, where… the noble pedal-point harmonies symbolise the swinging of golden censers, as the supplications of the friends and of the church rise up to the throne of God.

From the unsigned review in the Manchester Guardian, 13th March 1903

The Manchester Evening News review makes similar comments: ‘The semi-chorus which play an important part in the scheme were most successful. They maintained the pitch accurately, the quality of tone was excellent, and in every respect, save the one of attention to the minute marks of expression, their difficult task could not have been better accomplished.’

Ernest appeared in the semi-chorus in a second performance of Gerontius in November 1903. The performances were such a success, that when a three-day Elgar Festival was organised at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden the following year, the first such festival to be curated for a living composer, Richter brought down the Hallé Orchestra and members of his choir, including Ernest in the semi-chorus, to perform Gerontius again. The reviewer for The Times considered the performance ‘in many ways an admirable one, in spite of the inevitable incongruity of the surroundings’. Having been to the Royal Opera House many times I can appreciate his concerns, especially given where the chorus were placed. As the reviewer writes: ‘The performers were placed on a large orchestra [sic] erected on the stage, at the back of which the full chorus were placed – so far back, indeed, that their voices made a good deal less than the effect anticipated.’ However, he goes on to write that the ‘Manchester chorus and a semi-chorus of chosen singers did their parts well.’ Ernest was obviously also pleased with the experience and would include it amongst his list of achievements on his professional CV (see below).

Ernest sang in further performances of Gerontius in the March and November of 1905, and in all of these performances thus far he was billed in the concert programme either as ‘Mr Houghey’ or ‘Mr A.E. Houghey’. This is where my research began to get a little confused, because the programme for a Hallé performance of Gerontius in November 1906 has listed amongst the semi-chorus a ‘Mr E. Howie’, and the Hallé performance archive as a result has ‘Houghey’ and ‘Howie’ as separate entries. However, as I dug deeper into this story I realised that A.E. Houghey and E. Howie were the same person, a fact corroborated by Kristene Vaughn.

What had happened was firstly that Ernest had become a student at the Manchester School of Music and secondly, to perform under its auspices he had decided to give himself a stage name, namely ‘Ernest Howie’. I can only assume that a) he was worried that people would mispronounce the surname Houghey and guide them towards the right pronunciation by spelling it more phonetically and b) since he was known by his second given name anyway he would take that as his first name. Whatever the reason for the change, it suggests that he must have started his studies at around this time, and from this time on he was always ‘Alfred Ernest Houghey’ when appearing in a personal capacity, such as on census forms or later business dealings, and ‘Ernest Howie’ when appearing in a musical capacity.

The Manchester School of Music is not to be confused with the Royal Manchester College of Music, which later merged with the Northern School of Music to become the present day Royal Northern College of Music. It was founded in 1892 by a Manchester instrument dealer, Albert Cross, to provide teaching in music, elocution and foreign languages, and at the time Ernest started it studies it would have recently moved into new premises in Albert Square. As an institution it continued well into the era of the RNCM, finally closing its doors in 1994. The school regularly put on concerts and recitals in Manchester venues such as Houldsworth Hall in Deansgate, and students training to be opera singers would mount fully staged productions in theatres in Manchester and beyond.

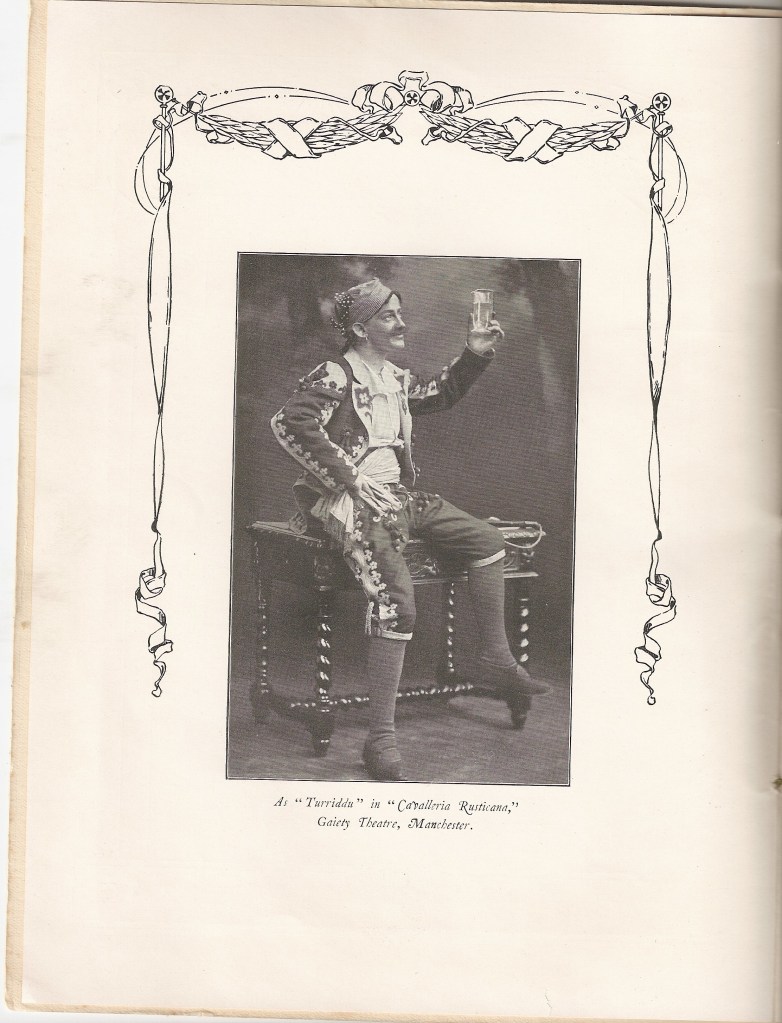

In March 1908 Ernest appeared in his first such production, a performance of Mascagni’s one-act opera Cavelleria Rusticana, which was part of a double bill with Bizet’s Djamileh. He played the lead tenor role of Turridu and photographs of the production show him in all his Sicilian peasant finery. The reviewer in the Manchester Courier appreciated the nature of the students’ undertaking: ‘We are glad to see the Manchester School of Music persevering in its determination to give the students annual opportunities of testing their powers in opera under ordinary stage conditions, for such experiences are just as necessary and invaluable to the young pupil who one day hopes to win renown in opera’, which final sentiment certainly applied to Ernest. The orchestra, conducted by Albert Cross himself, were obviously also students and the reviewer thought them ‘decidedly in advance of the standard of previous performances of the School of Music.’ He was generally praising of the female principals, but not so much of the male principals, writing that one ‘sang better than he acted’, and that the two tenor principals, which would have included Ernest, ‘were lacking in the requisite vocal strength.’

The production was reprised at the Gaiety Theatre in London, as reported by a correspondent in the Ladies’ Field magazine who wrote that ‘a considerable measure of talent was discernible in the performances recently given by the Manchester School of Music at the Gaiety Theatre’, and went on to say that ‘In “Cavelleria Rusticana” praise especially pertains to Miss Clara Broadbent, Miss Bessie Wood, Miss F. Hayward and Mr. Ernest Howie, who gave an effective rendering of their music.’

The following April saw Ernest appearing in the school’s 1909 production of Daniel Auber’s now largely forgotten opera Le Domino Noir, a somewhat unlikely looking tale of novice nuns and nobility in 18th century Spain. Ernest played the lead tenor role of Count Horace, who falls in love with the aforementioned novice nun. The performance was staged at the Midland Hall, a short-lived theatre space attached to the Midland Hotel in Manchester. The reviewer in the Manchester Courier noted the ludicrousness of the plot but wrote that ‘our bewilderment must not be laid to the charge of the performers, who, on the whole, annunciated their words clearly enough and acted with spirit and intelligence.’ Similarly, when moving to Ernest’s performance, he wrote that ‘Mr. Ernest Howie and Mr. R. Reginald Jackson made the most of their difficult parts, and more than reconciled us to the fatuous words they had to sing.’

By 1911 Ernest had graduated from the School of Music and at the age of 30 was looking to start a career in opera. As we can see from his entry in the 1911 census, however, he was not yet able to support himself from his music and is listed as being a ‘secretary to wholesale cosmetics’.

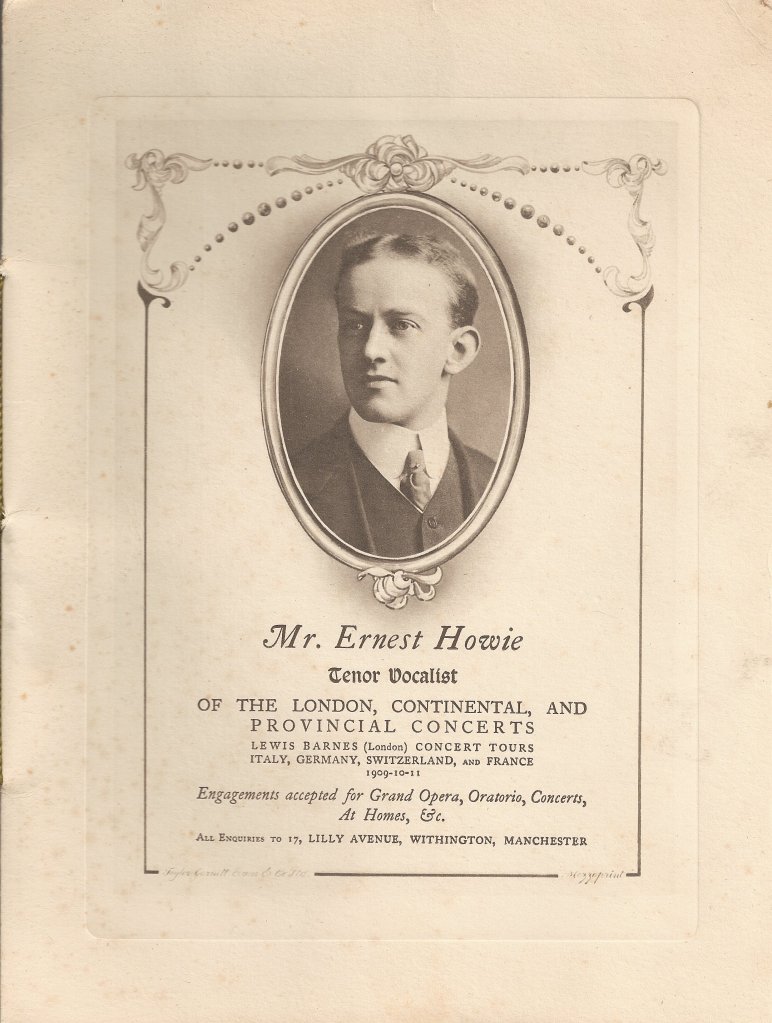

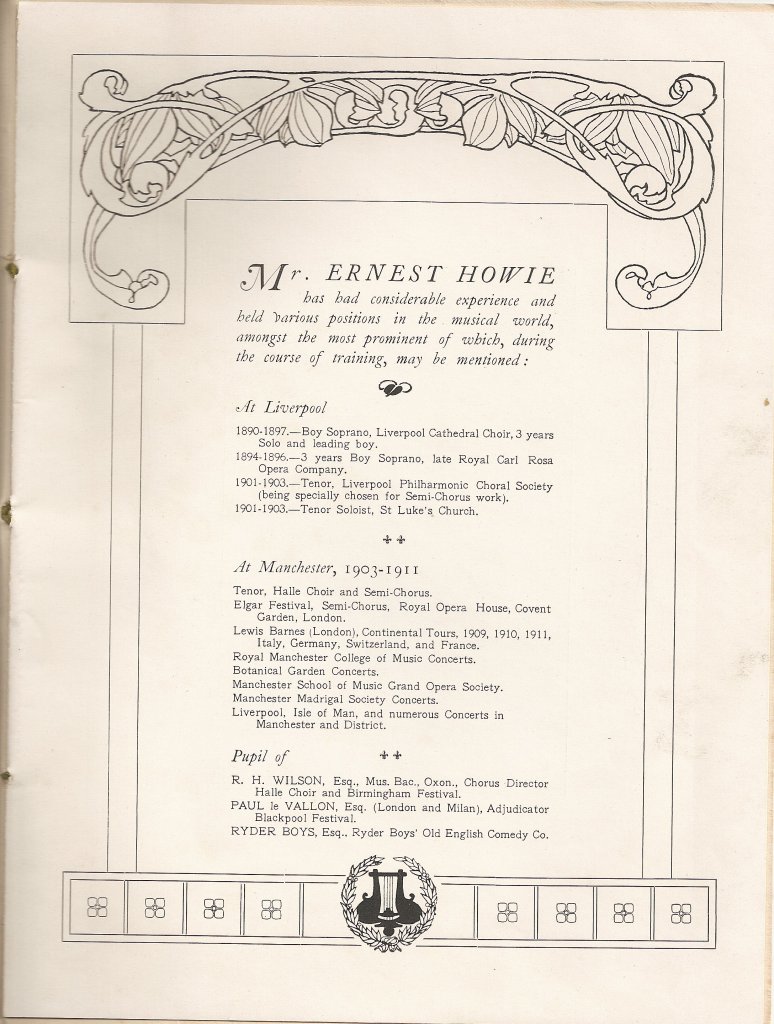

To promote himself he produced a very professional looking brochure that has been handed down through his family. It was effectively a CV for his work to date, including the photos from the opera productions that I have reproduced above, a list of his musical accomplishments in both Liverpool and Manchester, his teachers (who included R.H. Wilson, the aforementioned director of the Hallé Choir), and testimonials from various individuals associated with his career thus far. These included one from Albert Cross of the Manchester School of Music who wrote:

I have every confidence in recommending MR. ERNEST HOWIE as a smart artistic singer. His rendering of the parts of ‘Turriddu’ [sic] in Mascagni’s ‘Cavalleria’ and ‘Count Horace’ in Auber’s ‘Le Domino Noir’, both of which he played for me, gave me much satisfaction

Testimonial from Albert J Cross, May 8th 1911

Note that Ernest’s accomplishments also included work done with the Royal Manchester College of Music and concert tours undertaken to Italy, Germany, Switzerland and France under the auspices of Lewis Barnes of London.

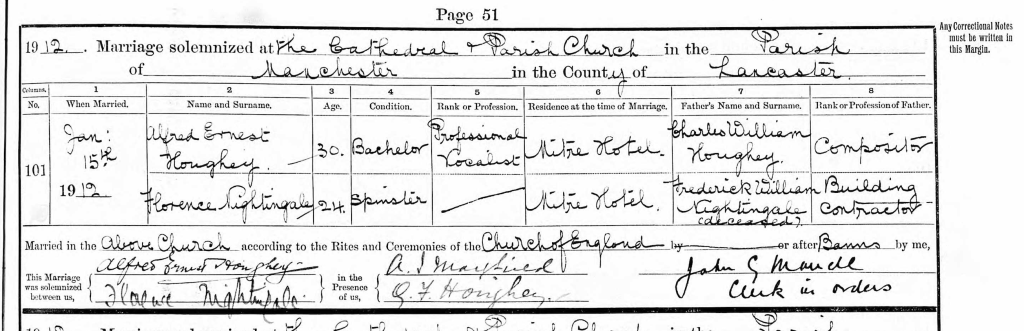

Note also that the contact address printed on the brochure was 17 Lily Avenue, Withington, the house he shared with his sister Blanche. This was not to be his home for much longer, however. He had met a woman six years younger than himself who gloried in the name Florence Nightingale, and they were married in January 1912 in Manchester Cathedral. Whether Ernest had been involved with the cathedral in a singing capacity I have been unable to uncover but nonetheless it was a prestigious venue in which to get married and one that allows us a glimpse at the registry entry. This shows that at the time of the wedding the couple were both resident at the Mitre Hotel, which still exists just across the road from the cathedral. This suggests that they were no longer permanently resident in Manchester and this is borne out by the fact that Ernest’s membership of the Hallé Choir lapses in 1911 and from 1912 we start seeing references to Ernest Howie appearing in concerts in the south of England.

The first such appearance I was able to find was in April 1912. As maybe befits a newly trained soloist, it was a relatively small event, a performance of Edmund Turner’s now probably justly forgotten Lenten cantata Gethsemane to Golgotha at Addlestone Church, Surrey, in which Ernest sang the role of Pontius Pilate. The reviewer in the Surrey Herald stated that the soloists ‘without exception, ably performed the respective parts allotted to them’. It was not Covent Garden, but it was a start.

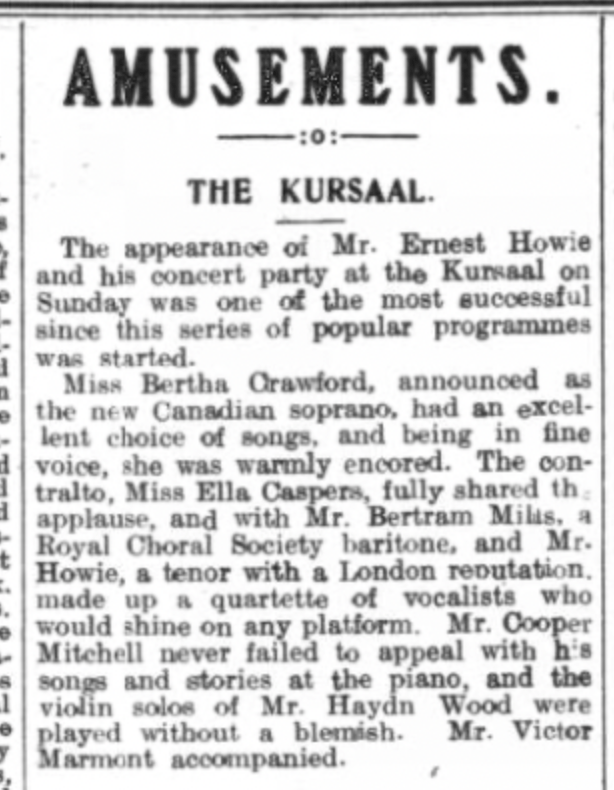

In May 1912 we see Ernest organising his own concert party and appearing at the Kursaal in Bexhill-on-Sea, the predecessor to famous Grade I listed De La Warr Pavilion. I talked about concert parties in the previous blog with regard to Margaret Hudson and this would have been along similar lines as hers with a mixture of light classical vocal and instrumental pieces and humorous songs and stories from the pianist. The Bexhill-on-Sea Observer reviewer thought it ‘one of the most successful since this series of popular programmes was started’. Ernest, ‘a tenor with a London reputation’ helped make up ‘a quartette of vocalists who would shine on any platform’. Note the presence of Haydn Wood on violin. He had studied violin and composition at the Royal College Music and would become one of the most popular composers of light music of the first half of the 20th century, his fame beginning with the publication of his hit song Roses of Picardy, which he wrote for his wife Dorothy in 1916, and continuing on to pieces such as Horse Guards, Whitehall, which became the signature tune for the long running BBC Radio programme Down Your Way. As for the soprano Bertha Crawford, newly arrived from Canada as the report says, her story, especially her escapades in Poland and Russia during World War 1, is much too rich and fascinating to summarise here. I would urge you to search for ‘Bertha May Crawford’ on Wikipedia. The fact that Ernest was performing with, and indeed organising, performers of such stature suggests that his career at this stage was on the right track.

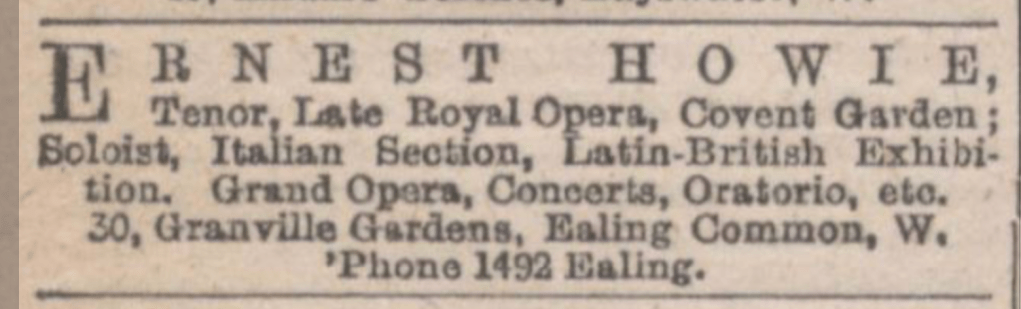

To further his career in that same year Ernest also took to advertising in the acting profession’s trade journal The Stage. He had a London address and phone number, though of course they may have been his agent’s rather than his own, and advertised himself as being open to ‘Grand Opera, Concerts, Oratorio, etc.’.

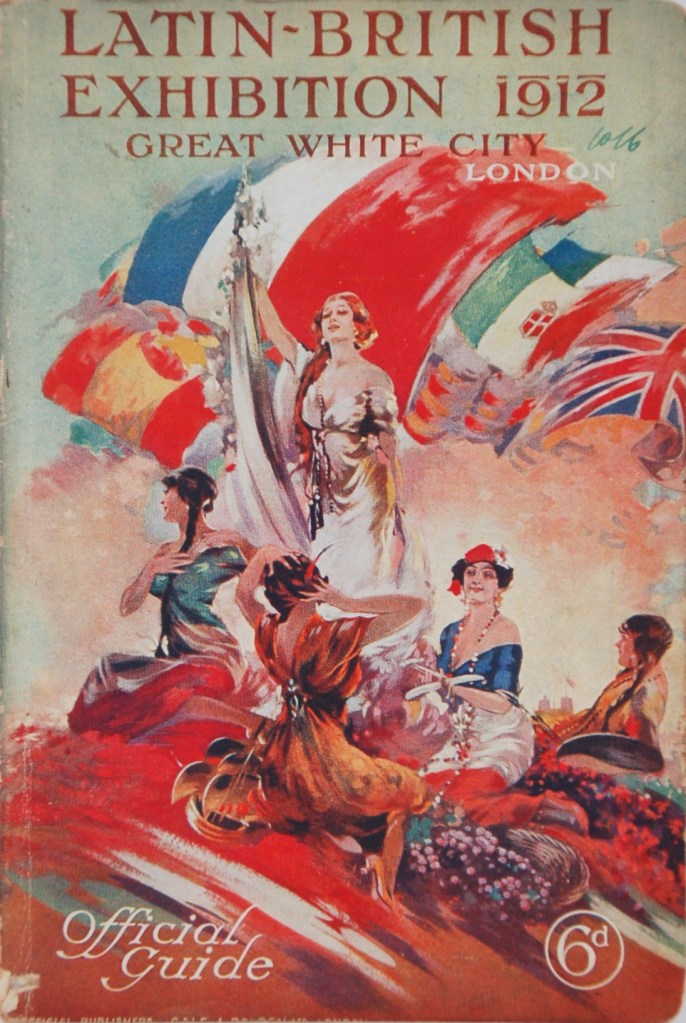

In his brief resumé he mentions Covent Garden, maybe a reference back to his appearance in the Elgar Festival eight years previously, and also an appearance as a soloist in the ‘Italian Section’ of the Latin-British Exhibition. This was a very recent event that had taken place at the White City exhibition grounds in West London, on the site now occupied by the Westfields Shopping Centre. The exhibition was designed to showcase the art and culture of the Latin countries of Europe and South America, including art treasures and a series of themed exhibits and fairground-style rides to entertain the visitors. It also advertised ‘alfresco promenade concerts by the Grenadier Guards and three other famous Military Bands’, and concerts of Neapolitan music, which presumably featured Ernest as an operatic soloist.

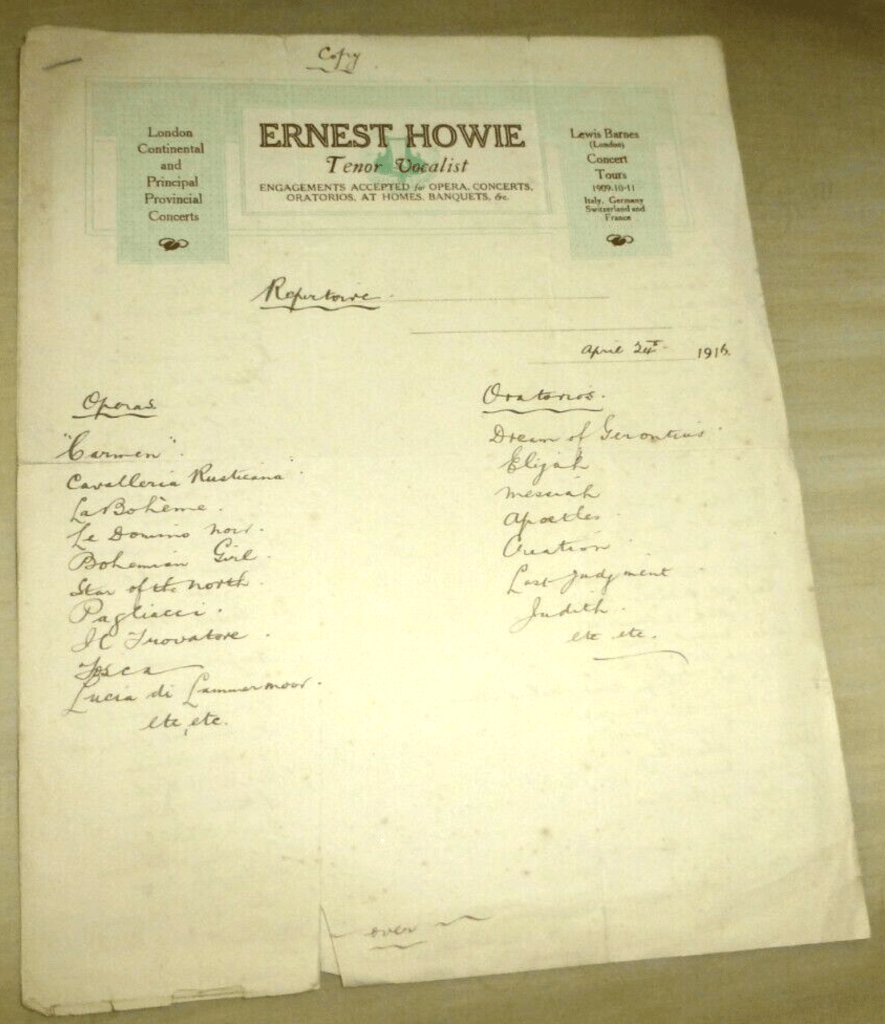

1914 saw the outbreak of the First World War. Ernest was not called up for active service, but continued plying his trade as an operatic tenor in what must have been trying circumstances. He was also still promoting himself, as we can see from the headed notepaper from April 1916 on which he has written both his operatic and oratorio experience, presumably for a prospective client or agent. Remarkably, at the time of writing this list is available to buy on eBay! In the opera column you will notice the operas he performed with the Manchester School of Music, Cavelleria Rusticana and Le Domino Noir. I love the use of ‘etc etc’ at the end of the list as if there is no end to his operatic experience – such is the way artists have had to promote themselves from time immemorial! The oratorio list includes many of the works he would have sung with the Hallé Choir, such as Dream of Gerontius, Messiah and Elijah.

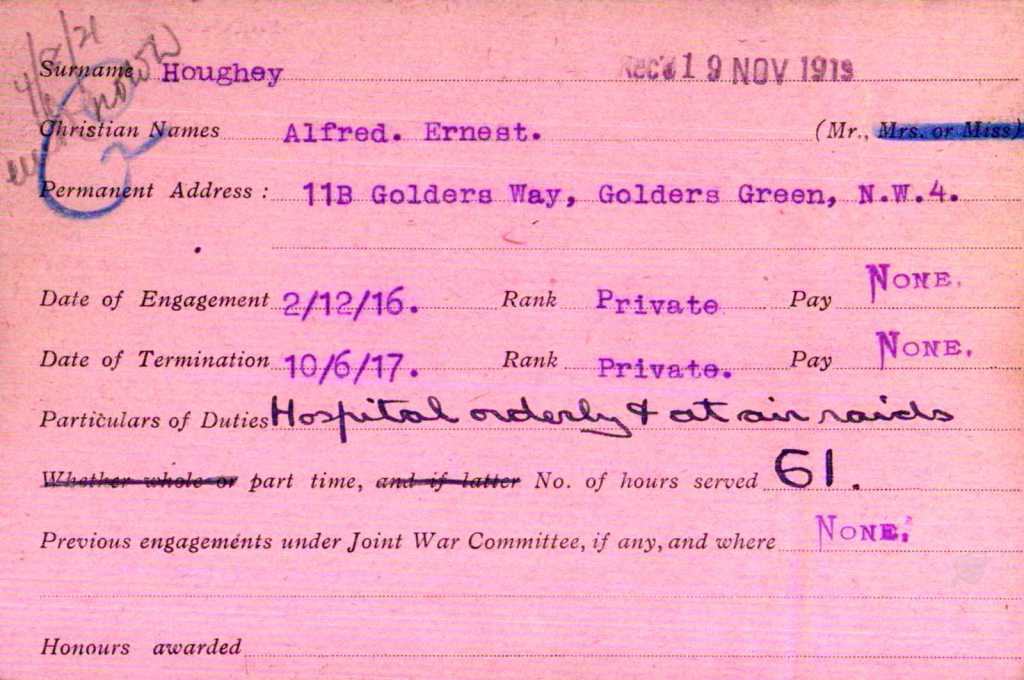

He did make a contribution to the war effort as is shown by this record of his service as a volunteer for the Red Cross between 1916 and 1917. During the First World War the Red Cross volunteers were organised into Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) and Ernest was attached to the Middlesex VAD Number 15 (Spalding Hall). The volunteers did a variety of work, from nursing to transport duties, the organisation of rest stations and hospital work. The record shows that Ernest worked as a hospital orderly and as an air raid warden. Though bombing raids were nowhere near as severe as they would be in the Second World War, but particularly at this time Zeppelin airships were a distinct threat. As we will see, Ernest would later have further direct experience of bombing.

Note that the record also shows that Ernest now had a permanent address in London, 11b Golders Way, Golders Green, which sounds impressive but was in fact a tiny flat at the back of a row of shops close to Golders Green Underground station. Crucially, however, it was a London base from which he could further his operatic aspirations, and indeed at around this time he started to appear with Sir Thomas Beecham’s Grand Opera Company. Thomas Beecham, heir to the St Helens based Beecham pharmaceutical company, baronet, conductor, impresario and generally large- than-life character formed the Beecham Opera Company during the First World War in 1915 as Britain’s first permanent opera company. Financial problems that often seemed to beset Beecham caused the company to collapse in 1920 but during its brief history it attracted first-rate soloists and conductors.

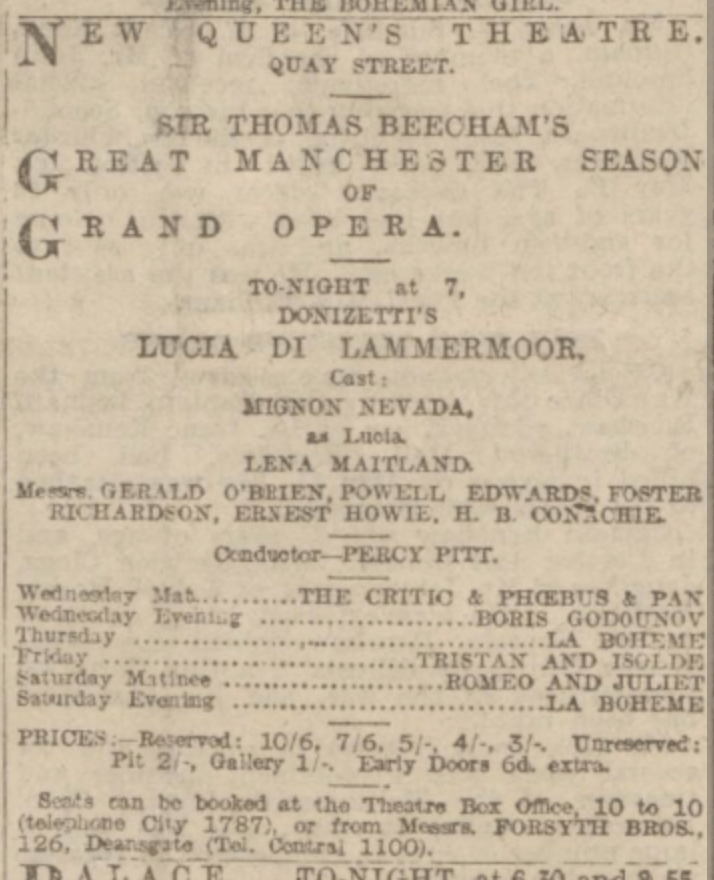

In May 1916 it was obviously in full health and we see an advert in the Manchester Evening News for a performance of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor by the Beecham company at the New Queen’s Theatre in Quay Street, Manchester, the building now known as Manchester Opera House. Included amongst the advertised soloists is Ernest Howie, returning to Manchester, and we can see that the season would include a host of other well-known operas. Ernest was too far down the cast to be mentioned in a brief review in the same paper of the opening performance of the opera, but the opening line suggests the production was well received: ‘A few more performances as musically perfect as that given on Saturday night would probably break down the unreasoning prejudice against the old form of Italian opera.’

In February of the following year we an advertisement in the Birmingham Daily Post for a performance by the Beecham company of Saint-Saëns’ biblical opera Samson and Delilah at the Prince of Wales Theatre, Birmingham, conducted by Percy Pitt. Again Ernest Howie is named in the cast. Though this was again a minor role, he impressed the reviewer in the Birmingham Daily Gazette enough to mention him alongside the lead male soloists Walter Hyde, Frederic Austin and Normal Allin: ‘As a Philistine good work was done by Ernest Howie’.

We lose track of Ernest between 1917 and 1922, when out of the ashes of the Beecham Opera Company, which had gone into liquidation in December 1920, emerged the new British National Opera Company, with Percy Pitt rather than Beecham as its first artistic director. Though there is no direct link with either of them, this idea of a national opera company would reach fruition with the creation of the Royal Opera and English National Opera after the Second World War. Like the Beecham company, however, although they reached high artistic standards they had financial problems throughout their short lifetime and were wound up in 1928 with the assets taken over by a new company, the Covent Garden Opera Company, whose first musical director was one John Barbirolli.

The new company gave its first performance in February 1922 at the Alhambra Theatre, Bradford, at that time a relatively new theatre and one very much still alive today. As you can see from the advert in the Bradford Daily Argus, like the predecessor company they would perform a large number of different operas during a season in any given theatre. They opened with Verdi’s Aida, and amongst the cast, performing the role of the Messenger, was Ernest Howie. The review in the Leeds Mercury was extremely positive, describing the performance as ‘an operatic triumph’ and Ernest received a mention in dispatches: ‘Mr Ernest Howie as the Messenger completed a thoroughly good cast’.

June 1922 should have been a cause for some satisfaction as Ernest made it back to the stage of the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden to sing with the British National Opera Company in a single performance of Wagner’s Tannhäuser conducted by Eugene Goosens,. He was the middle of three famous musicians bearing that name and the father of a number of renowned artists including the third Eugene, the harpist Sidonie and the oboist Léon. Sadly, the production was not well received by The Times, which described it as ‘an unequal performance’ that had ‘the character of a rough-and-ready improvization. The reviewer felt that for the National Opera Company to ‘fare better than its predecessors at Covent Garden it must avoid at all cost the reputation for giving “scratch” performances’. The reviewer for The Era was slightly more charitable, praising some of the soloists without saying a great deal about the production. It did made mention of Ernest, however: ‘As Henry and Reinmar, Mr. Ernest Howie and Mr. Frank Le Pla were more than adequate.’

So yes, it should have been a cause for satisfaction, but Ernest was now 41 and had two young daughters to support, Florence Evelyn and Doris Diane, born in 1913 and 1917 respectively. Yes, he was appearing on the stage of the Royal Opera House but he wasn’t yet singing the big roles, the kind he had sung 15 years previously as a student, but rather the minor roles down the bill that only occasionally merited a review in the papers. However, as we have seen in the way he promoted himself in his early days as a professional singer, Ernest was a focused and determined man and decided to make a complete career change.

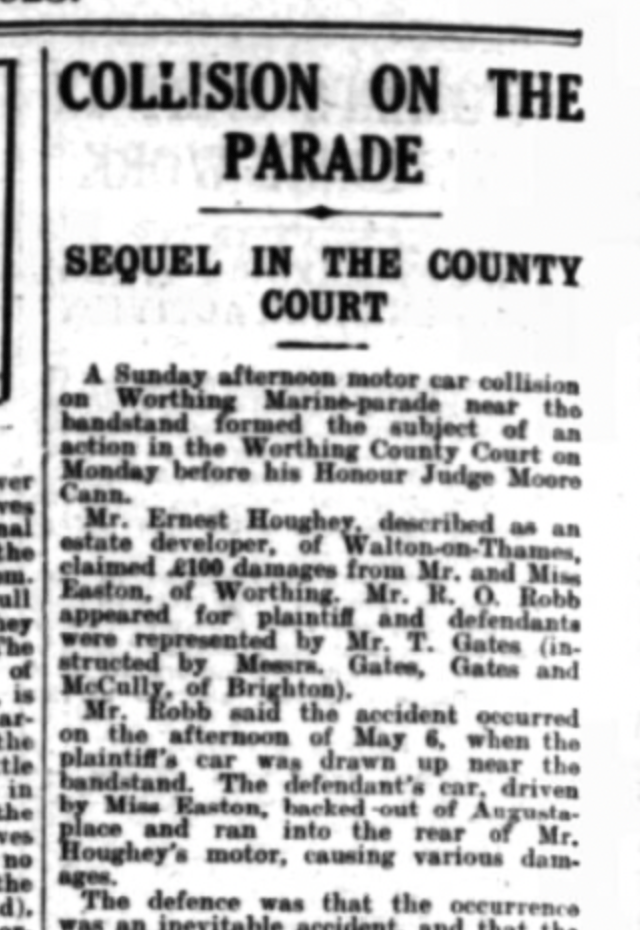

We know about this change, bizarre as it may seem, from county court reports in the local Worthing newspapers in December 1923. We first read a report in the Worthing Herald on the 15th December that describes a collision on Marine Parade in Worthing between two cars, one belonging to Ernest Houghey of Walton-on-Thames and one driven by an Edith Easton and her brother Harry. Houghey is described as an ‘estate developer’. Edith Easton’s car had backed out of a side road into the rear of Houghey’s car and he was claiming £100 in damages because with his car being out of action he was having to travel by train from Walton to Worthing for his work rather than drive. The judge gave in favour of the plaintiff but only with regard to the damage to the car and Florence Houghey’s dress, and the cost of taking the car back to London, a total of £27 5s. He did not award the cost of train travel ‘owing to the plaintiff’s method of giving evidence’!

Is this our Ernest? He is obviously well off for the time. He not only owns a Belsize motor car, but according to the report he employs a chauffeur to drive it. The answer comes in another report of the same case, this time in the Worthing Gazette, where part of the report reads: ‘Cross-examined by Mr. Gates, the plaintiff said he was formerly a professional singer, but since June last year he had been in business as an estate developer.’ So yes, this is our man, and he was engaged in one of the most important activities of the inter-war years, house building.

At the end of the First World War the Prime Minister David Lloyd George, in an address that became known as the ‘homes for heroes’ speech, made a commitment to honour the sacrifice of those who had served on the front line in that war to end all wars by providing ‘habitations fit for the heroes who have won the war’. This commitment was made flesh a year later by the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919, also known as the Addison Act, an act that in the words of Professor John Bryson, ‘imposed a duty on every local authority to survey housing needs and to make and carry out plans. It also guaranteed a state subsidy. The Addison Act was the start of a long tradition in the UK of housing provided by the state for the people’. This was followed by two further acts in 1923 and 1924 which encouraged public sector home building and local council house building respectively.

There was therefore money to be made in house building especially in towns close to London catering for overspill from the city, and Ernest had obviously got in on the ground floor in setting himself up in just such a town, namely Walton-on-Thames. Assuming he hadn’t dipped his toe whilst still active as a professional singer he had obviously made great strides in the 18 months since what must have been his last professional engagement at Covent Garden in June 1922. This is further evidenced by the fact that the 1926 Surrey Electoral Register finds him living with his family in Ashley Cottage, Oatlands Drive, Walton-on-Thames close to the site of Oatlands Palace, built by Henry VIII for his fourth wife Anne of Cleves. It may have been nominally a ‘cottage’ but Ashley Cottage is now a grade II listed building, described as being early 18th century in rendered brick.

Ernest Howie was no more, replaced forevermore by Alfred Ernest Houghey. Except was he? I found one further reference to ‘Ernest Howie – tenor’, from 1929 in the unlikely setting of the Penistone, Stocksbridge and Hoyland Express in South Yorkshire. It was a report of a performance of ‘the delightful musical play Katinka, by the Barnsley Amateur Operatic Society. Way down the cast list we see a reference to Ernest Howie singing the role of Henry. Could this be our Ernest Howie in one final performance, maybe helping out an ex-colleague, before final retirement? Unless someone can confirm one way or another I suppose we will never know, but I do know from my researches that tenors called Ernest Howie are very thin on the ground!

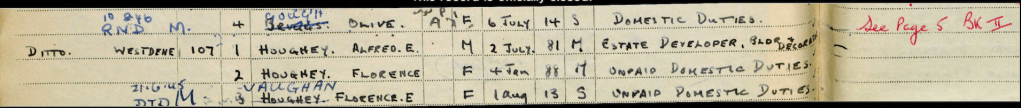

We next pick up Ernest’s story around the time of the beginning of the Second World War in 1939. Immediately after the outbreak of war a quick census was taken of the civilian population of England and Wales which included recording name, date of birth, marital status and occupation. These details would be used to create the identity cards and ration books that people would use through the war, and also for conscription purposes. As you can see below, ‘Alfred E.’ Houghey had moved his base of operations from Walton to the village of Barnham in Sussex, close to the seaside resort of Bognor Regis, and was listed as an ‘Estate Developer, Bldr and Decoratr’. He lived in a house known as Westdene in West Barnham, an area of large detached villas well suited to a person of Ernest’s stature. He was living with his wife Florence and his daughter Florence Evelyn, who would soon become very important to Ernest’s ongoing story. His younger daughter Doris had married Hubert Baldwin in 1938 and so had moved away from the family home.

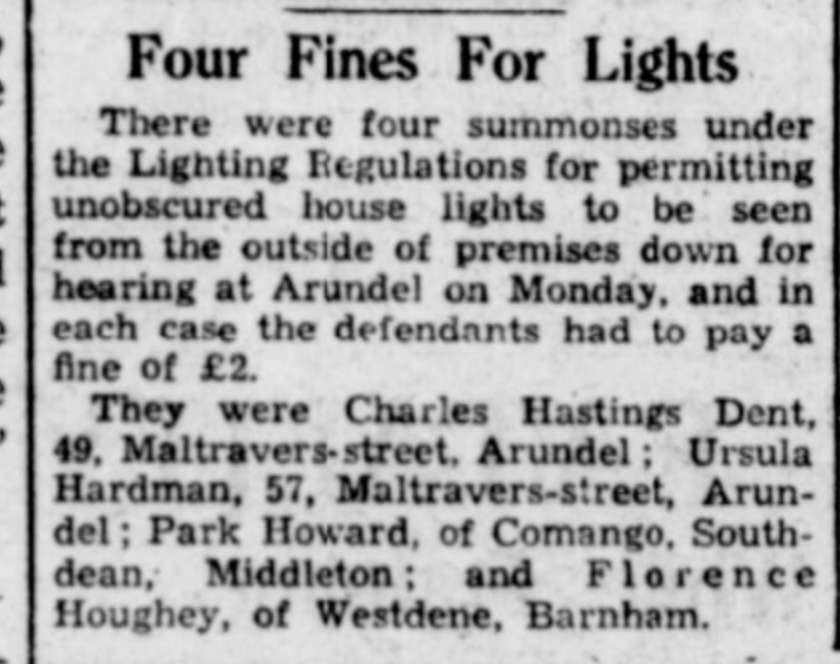

We see three futher references to the Houghey family during the Second World War. The first relates to the blackout that was enforced throughout the war to ensure that no houselights or other external lights were visible from the air and therefore able to assist German bombers. Any infringements were met with fines and I am sure that most local papers had reports of such fines every week. The Littlehampton Gazette of 12th November 1943 certainly did, and we can see that one of the offenders for ‘permitting unobscured houose lights to be seen from the outside of premises’ was Florence Houghey, of Westdene, Barnham.

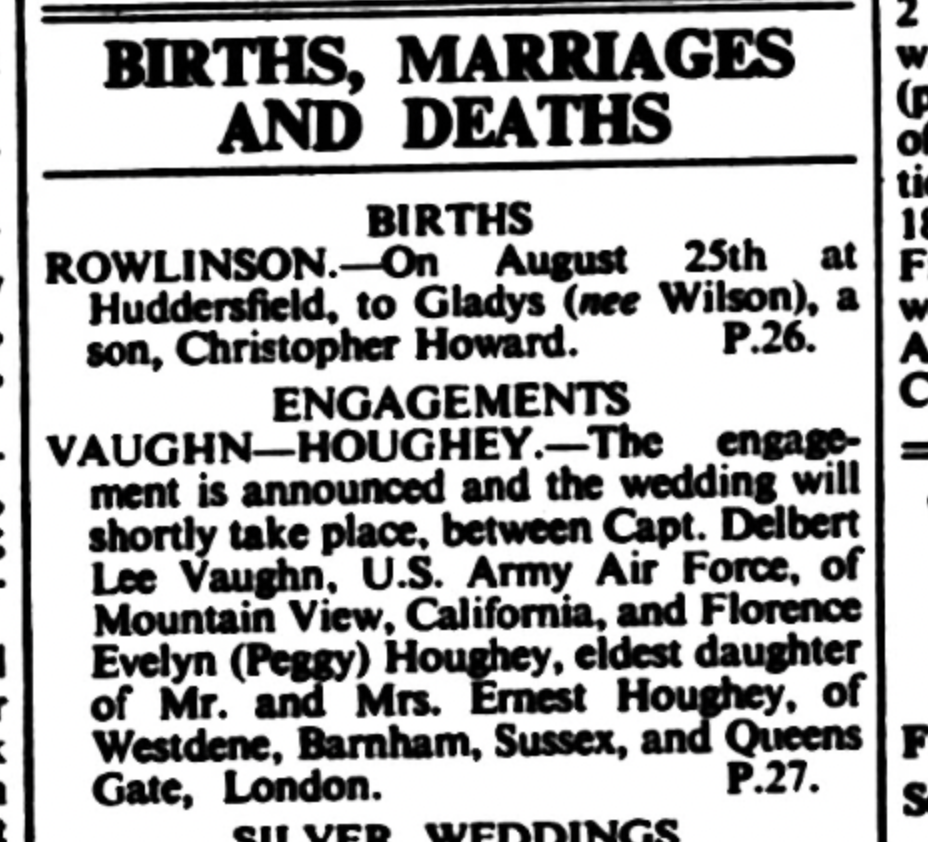

The second, much happier, reference came in the births, marriages and deaths column of the Chichester Observer in September 1944, in which the engagement was announced between Florence Evelyn Houghey, Ernest and Florence’s 31 year old daughter, and Delbert Vaughn of Mountain View, California, a captain in the U.S. Army Air Force. Florence Evelyn was to be, in what would soon become common parlance, a ‘GI Bride’. Note the addresses given for Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Houghey, not just their villa in West Barnham, but also ‘Queen’s Gate, London’. If the Hougheys also had a pied a terre in South Kensington, then they were doing very well financially.

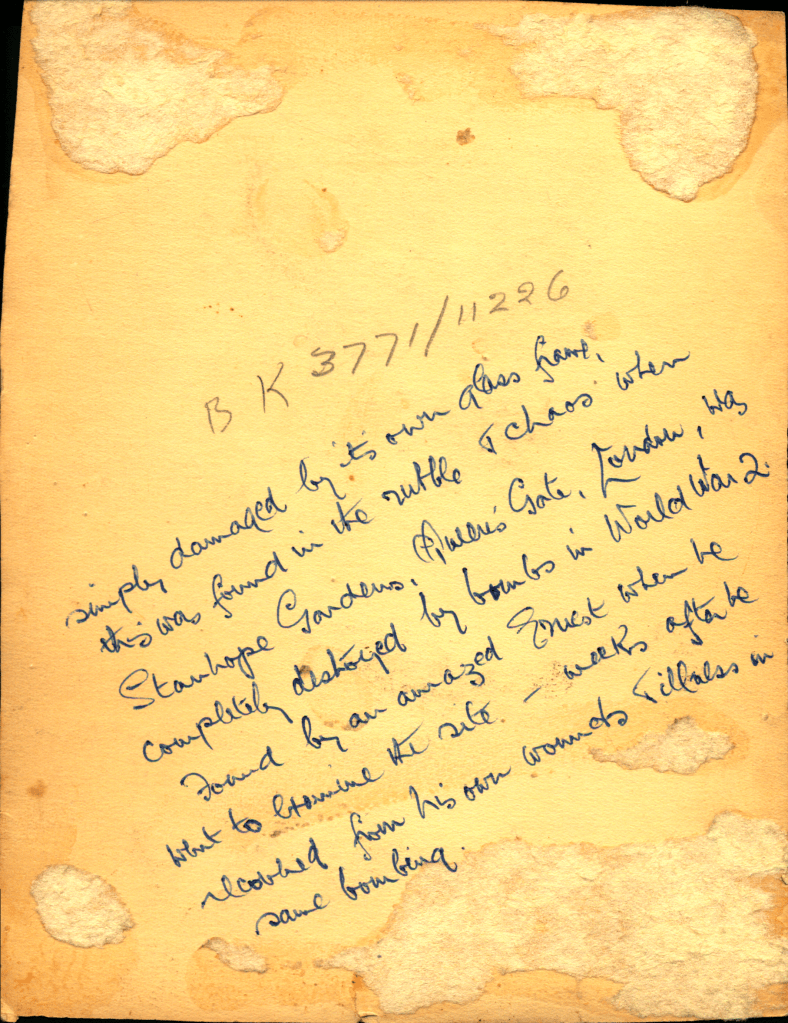

The third reference dates from before the previous one and shows how the war visited Ernest with a vengeance. It also confirms that they spent some of their time in London. It is the back of a photo on which has been written, presumably by Florence, that it had been recovered by Ernest from the rubble of Stanhope Gardens, Queens Gate some time after Ernest had himself been wounded in the same air raid that had brought about the damage.

Florence Evelyn and Delbert married on the 23rd June 1945 and their granddaughter Kristene believes that Florence was one of the GI brides who travelled across to the USA on the Queen Mary in 1946, and indeed that she was interviewed by Time magazine in the process. Sadly I have not been able to find any record of an interview but it could well be that she is one of these brides photographed on the Queen Mary at Southampton about to set sail on one of the crossings for America.

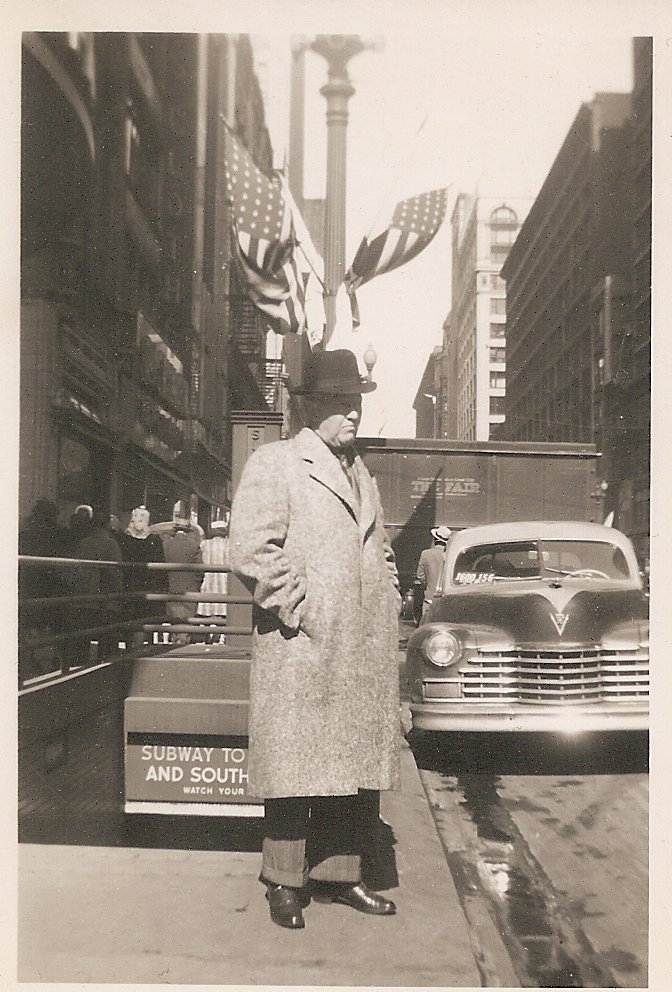

There now comes a twist that even exceeds that in 1922 when Ernest made the decision to give up singing professionally. One year after Florence Vaughn sailed across the Atlantic to be with her husband Delbert, we see Ernest Houghey (described as an accountant) and his daughter Doris sailing to the USA on the Dutch-registered transatlantic liner the S.S. Veendam to join Florence. Doris had divorced from Hubert Baldwin and had reverted to calling herself Doris Houghey. She would later remarry in America, becoming Doris Thiess. What is noticeable from the ship’s manifest below is that Ernest’s wife Florence did not sail with them. According to Kristene, the family believe that she intended to follow her husband but in the end never did.

We can speculate as to why Ernest decided to make such a momentous move, but he was now 65 and comfortably off. Maybe the attraction of a warm climate for his retirement, plus the presence of his daughters swung the scales.

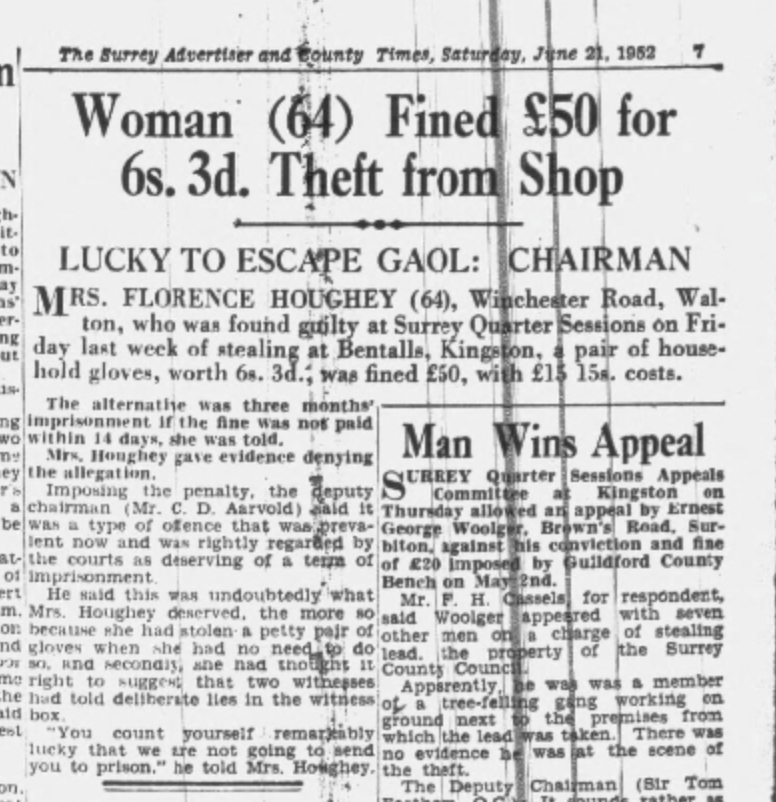

Back in England Florence Houghey made the decision to move back to Walton-on-Thames, leading to a unfortunate postscript to her story. In June 1952, five years after Ernest had moved west, the Surrey Advertiser reported that Florence Houghey, aged 64 (which would match with her birthdate), of Winchester Road, Walton, was found guilty at Surrey Quarter Sessions of stealing gloves worth 6s 3d from Bentalls department store in Kingston-on-Thames. She was fined £50 with 15 guineas costs, with the chairman of the sessions stating that she was ‘lucky to escape gaol’. Such a sad end to her side of this remarkable story. She lived on in Walton for another 14 years, dying in 1966, aged 78.

Ernest himself settled in Campbell, California, close to his two daughers, Florence in Los Gatos, and Diane in San Jose. There is one final picture of him looking happy and contented with his daughter Florence and her children on what would be his last Christmas in 1954. He died the following December, aged 74 and was buried in the historic Oak Hill Memorial Park in San Jose.

His brief obituary in the Los Gatos Times-Saratoga Observer only makes mention of his nearest relatives, Florence Vaughn and Doris Theiss, and his wife Florence back home in England. It says nothing of Liverpool Cathedral choir, the Carl Rosa Opera Company, the Hallé Choir and the Manchester School of Music, of Thomas Beecham, the Royal Opera House and the British National Opera Company, of Homes for Heroes, wartime bombing raids and GI brides. There is certainly no mention of that night 52 years earlier in March 1903 when, as a valued member of the tenor semi-chorus he became one of the first five members of the Hallé Choir to sing the opening words of the opening chorus of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, ‘Kyrie eleison…’.

It’s a long way from the Free Trade Hall to California, but such are the stories that can be told about Hallé Choir members. In the next final part of this series I will talk about another couple of semi-chorus members whose lives followed similar paths to Margaret Hudson and Ernest Houghey, though perhaps not as dramatically!

References

Special thanks to Kristene Vaughn for sharing some wonderful photos of her great-grandfather along with various pieces of publicity material. I’ve only been able to include a few of them here but they were invaluable in helping me get a picture of the man.

The research tools used were:

Ancestry ancestry.co.uk via Cheshire Libraries

British Newspaper Archive britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Guardian Archive via Manchester Libraries

Times Archive via Manchester Libraries

Hallé Archive

Extra information

Anon, ‘90,000 volunteers, one remarkable legacy’ British Red Cross, undated. https://vad.redcross.org.uk/volunteering-during-the-first-world-war

Anon, ‘Ashley Cottage – A Grade II Listed Building in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey’, British Listed Buildings, undated. https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101365886-ashley-cottage-elmbridge-walton-central-ward

Anon, ‘British National Opera Company’, OperaScotland.org listings & performance history, undated. http://operascotland.org/operator/98/British+National+Opera+Company

John Bryson, ‘Reflections on the 100th Anniversary of the Addison Act: Housing as a Social or Economic Asset’, University of Birmingham, undated. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/perspective/reflections-on-the-anniversary-of-the-addison-act

Richard Fletcher, ‘Manchester School of Music’, RNCM Archives, 16th October 2020. https://www.mdmarchive.co.uk/tag/9317/Manchester-School-Of-Music

Daniel Jaffé, ‘Thomas Beecham: master of the waspish one-liner. But an often visionary conductor too’, BBC Music Magazine, March 14th 2025. https://www.classical-music.com/features/artists/thomas-beecham

Brian Watson. ‘The 1912 Latin-British Exhibition’, Benjidog Historical Research Resources: White City, undated. https://www.benjidog.co.uk/WhiteCity/1912.php

Leave a comment