Introduction

During the course of writing this blog I have not touched in any great detail on how the Hallé Choir and other similar symphonic choruses are made up. At its simplest, of course, the voices within the choir are split into four voice parts, soprano (higher female voices), contralto (more commonly just called alto) (lower female voices), tenor (higher male voices) and bass (lower male voices). If we take a work like Handel’s Messiah we see that it is mostly written for just these four parts. However, each part is routinely further split into two more parts, so that we have soprano 1 and 2, alto 1 and 2, tenor 1 and 2 and bass 1 (often called baritone) and 2, with the ‘firsts’ as we call them generally singing in a higher register than the ‘seconds’. Occasionally, there are further splits, as for example in John Adams’ 20th century masterpiece Harmonium, a piece the Hallé Choir were rehearsing at time of writing, which has not only 4-part and 8-part writing, but also 12-part writing where each voice part is split into 3.

There are many works which are written for double choir, where two entirely separate groups of singers work off and against each other. Both of these choirs may also have music written for 8 parts, meaning the choir needs to be split 16 ways. Good examples of double choir pieces would be Mahler’s epic 8th Symphony and Poulenc’s sublime Stabat Mater. Often a work will be written in conventional 4 or 8-part harmony and then suddenly have a section for double choir, as is the case with the Sanctus in Verdi’s Requiem.

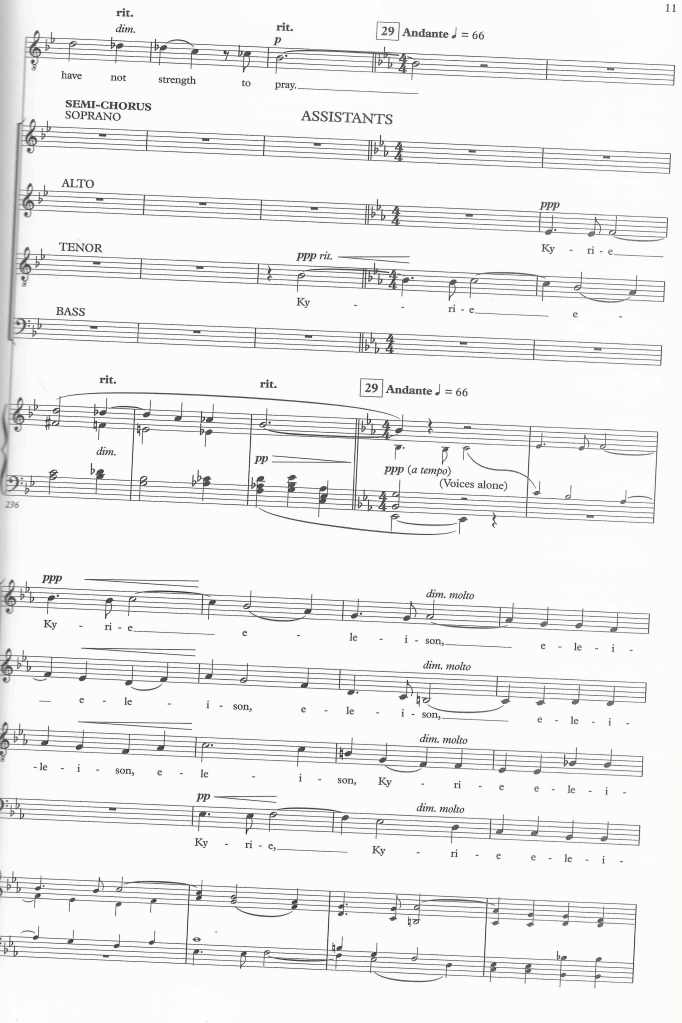

An extension of the double choir concept is the idea of having a semi-chorus. Here a small group of singers from within the choir will during the course of a piece emerge from the body of choir and sing a completely separate line that comments on or counterpoints the main choral line. Occasionally the composer will ask in a particular passage for the semi-chorus to sing alone, usually to provide a lighter texture, as for example in the second movement of Vaughan Williams’ A Sea Symphony (though this usually ends up being sung by the whole choir, just more quietly!).

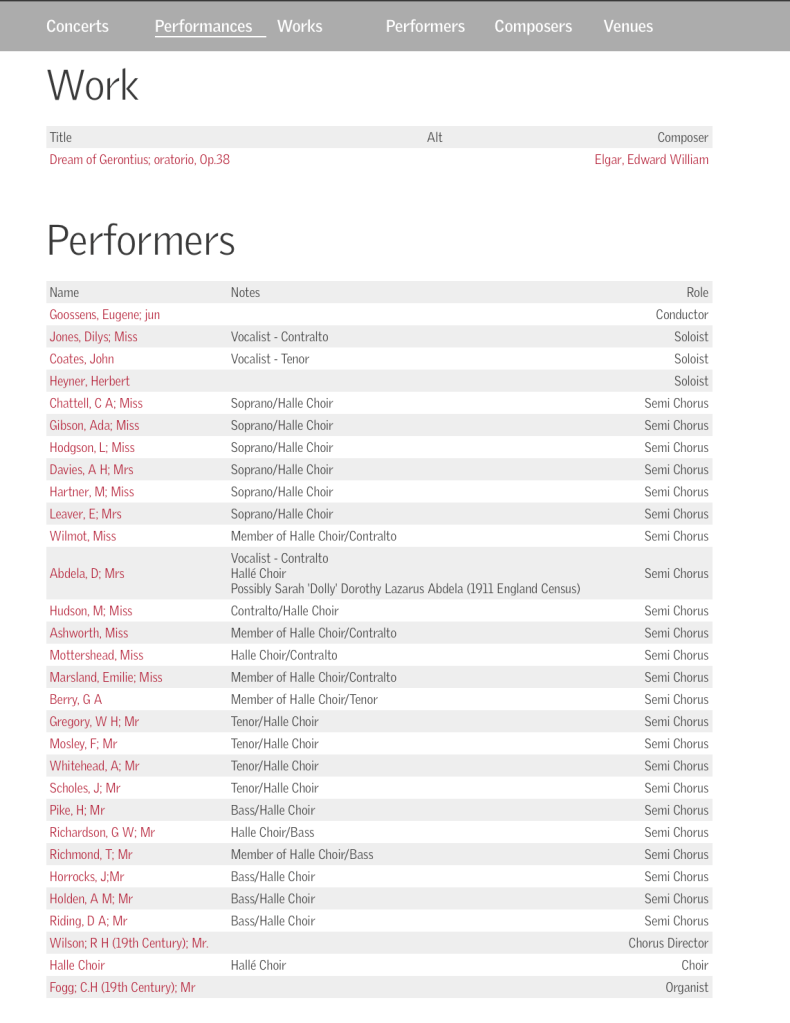

Edward Elgar made great use of the semi-chorus in his oratorios, especially in The Dream of Gerontius, a work long associated with the Hallé Choir. Indeed, as can be seen in the extract reproduced here, the semi-chorus are the first choral voices to be heard in the piece. In order to provide maximum contrast with the main choir in 21st century Hallé performances of the piece these voices are usually provided by the Hallé Youth Choir. Historically, however, the semi-chorus was always drawn from within the main body of the Hallé Choir, and it was the tradition between the first performance of Gerontius in 1903 up to the 1930s to indicate in the concert programme which members of the choir were singing in the semi-chorus. As a result they appear as separate performers in the Hallé’s recently launched performance and repertoire database.

As part of the Hallé Archive’s ‘Ancoats Story’ project myself and a number of fellow archive volunteers were asked to use newspaper archives and genealogical resources to try and find any stories that might lie behind some of the less well-known performers in that database. I was allocated performers beginning with the letter ‘H’ and soon found a number of fascinating stories, especially around these Gerontius semi-chorus singers. Over the course of the next few blogs I will attempt to recount some of those stories, and hopefully you will find them as fascinating as I did when uncovering them. They emphasise a number of characteristics of the choir, some of which can still be seen today, such as the links with the Manchester student body, then the Royal Manchester College of Music and the Manchester School of Music, now the RNCM and the University of Manchester; the attraction of the choir to people from the teaching profession; and the amount of music-making the choir members do outside of the choir. The stories also bring out the close links the choir had in its early days not only with the Anglican choral tradition that I talked about in my very first blog, but also a very specific non-conformist singing tradition. They also evoke a now largely lost world of competitive music festivals, and concert parties that epitomised the age.

I will begin with the story of Margaret Hudson, which began in the 1880s up in the foothills of the South Pennines and continued during a lifetime devoted to education and music up until the dawn of the era of Glam Rock in the early 1970s.

Note that with all of the singers I will be describing there was a large degree of detective work involved in identifying them given that all I had to go with was a simple surname and initial, which is how they appear in the archive, and oftentimes what appeared to be a good lead would turn out to be false. However, I am confident that in all of these stories, having eliminated people with similar names but incorrect address, birth dates that don’t fit the narrative and unlikely positions in life, and having used good old-fashioned circumstantial evidence, the person I have identified is the person listed in the relevant semi-chorus. If anyone knows otherwise, please let me know!

Margaret Hudson: Born in Bacup in 1881, Died in Manchester in 1971

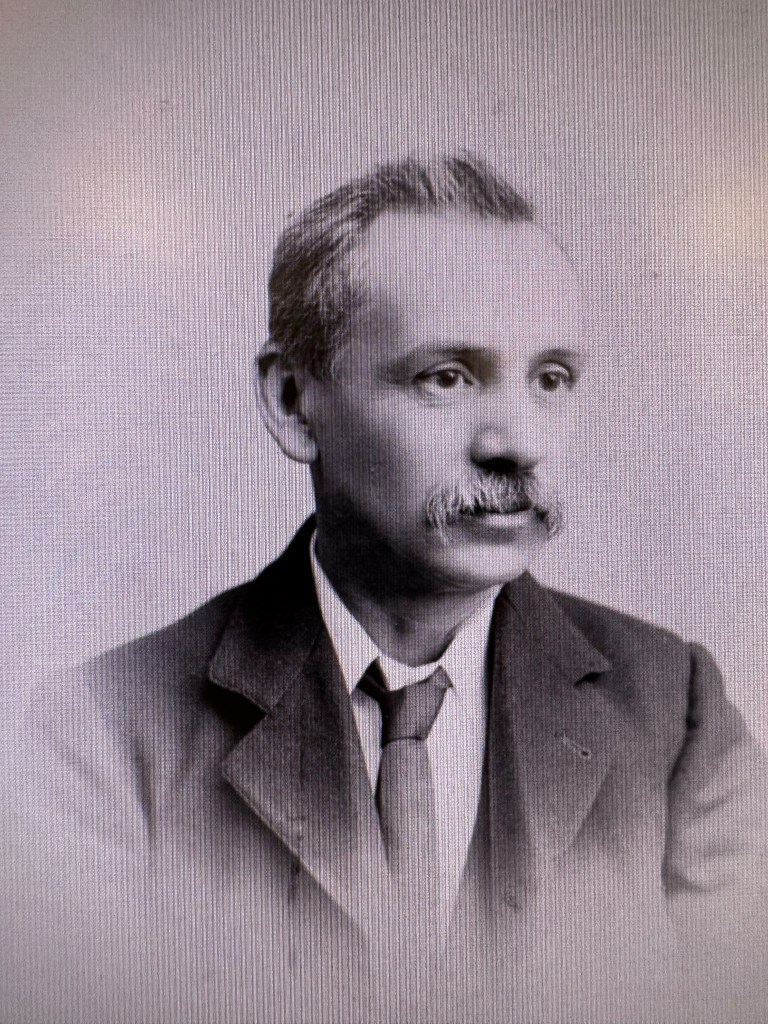

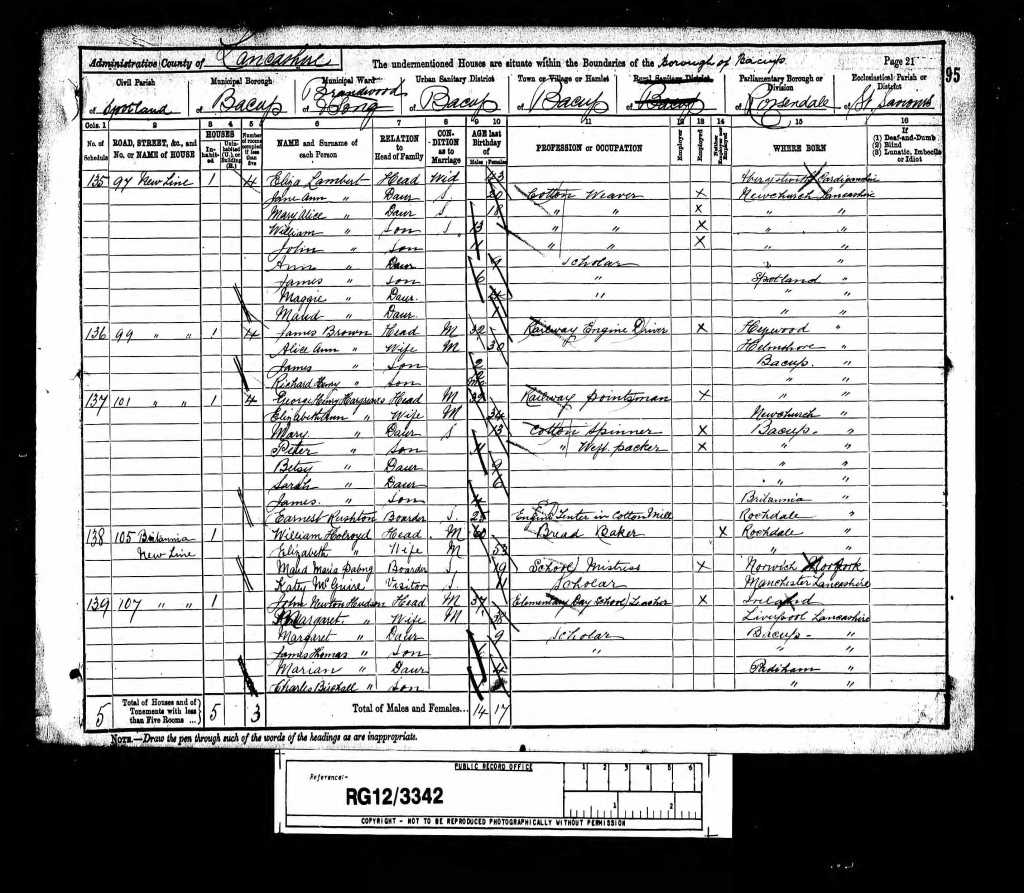

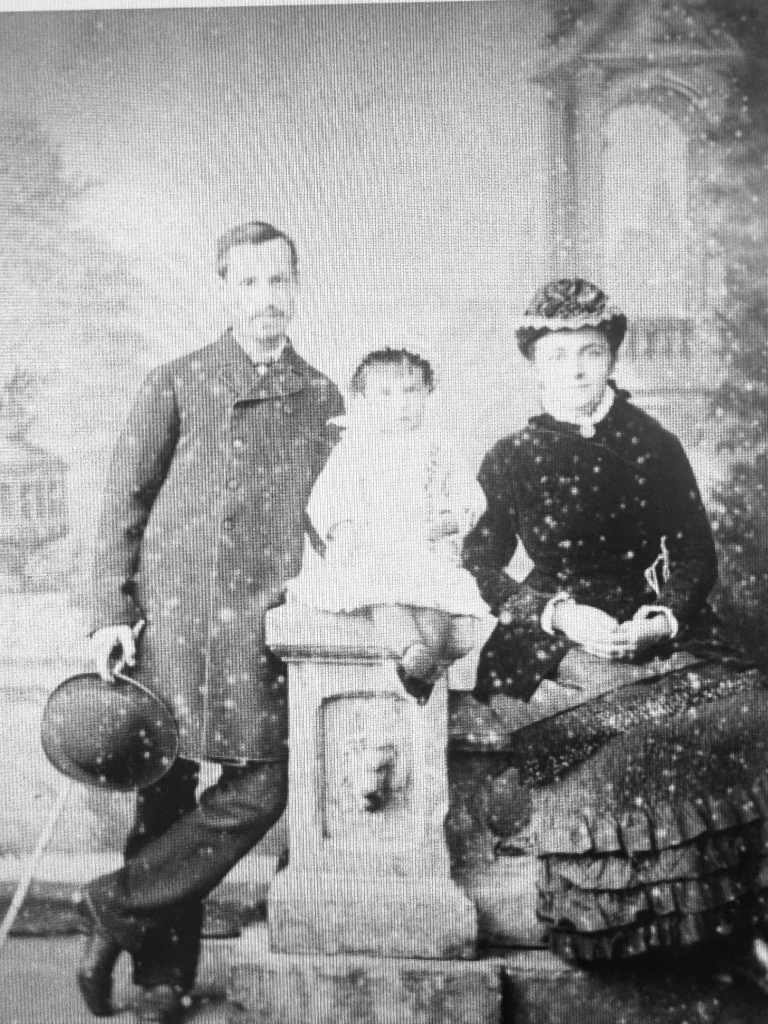

John Newton Hudson was born in Belfast on 3rd May, 1853. Although of Yorkshire stock, his father Thomas had moved to Ireland to work in the shipbuilding industry. Following the death of John’s mother Ann in 1861, Thomas remarried and moved the family to Liverpool to again work in the shipbuilding industry. In the 1871 census, Thomas, his new wife Sarah and their family were living in Toxteth Park. 1870 was a significant date in the history of education as it saw the passing of the Elementary Education Act which gave local authorities the power to set up schools for the teaching of children from the age of 5 to 12. Though true free local education took a while to arrive the act was obviously a milestone on the journey, and indeed, the young John Hudson is described in the 1871 census as being a ‘Pupil Teacher’. The pupil-teacher system was one that pre-dated the widespread availability of places at Teacher Training Colleges and involved senior pupils being enrolled in a form of apprenticeship over the course of five years so that at the end they could fulfil the role of a fully-fledged teacher. In taking on such a position John was consciously moving from the manual role that might have been expected of him given his origins. In 1883 the University of London began providing examinations for diplomas in education, and John must have been one of their first examinees as he is recorded in the University of London’s ‘General Register’ as matriculating in June 1885.

And indeed, by the time of the 1891 census he was living in Bacup, Lancashire, employed as an Elementary Schoolteacher. In the interim he had met and in 1877 married Margaret Ann Birchall, born a year earlier than him in Hindley. Their first child Ann was born in 1879 but sadly died in infancy, making Margaret, born in 1881, their oldest surviving child. Three more children had followed by 1891, James Thomas in 1885, Marian in 1877 and Charles Birchall in 1880.

Why they moved to Bacup, a small town in the Pennine fringes of Rossendale, is not clear, but at the time the mills were booming, especially the Britannia Mill which dominated the landscape of the part of Bacup in which they settled. Judging by the baptism record for James Thomas, they worshipped at the Britannia Wesleyan Methodist Church, so would have had an affinity with the mill and its workers, many of whose children John Hudson would have taught. Around this time John also began work as a Wesleyan lay minister, preaching in his free time, and the Wesleyan sensibility was, as we shall see, something he passed on to his children.

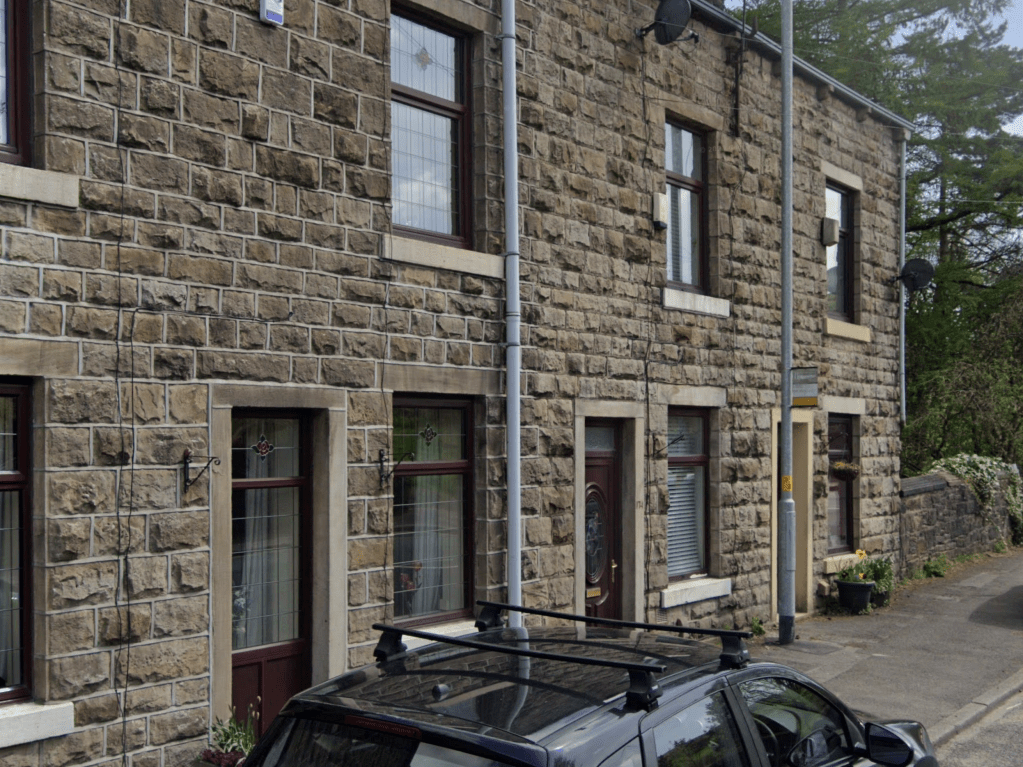

During the course of the following three decades, the Hudson family lived at three different addresses in the street known as New Line, so called because of its proximity to the New Line (or Britannia) tunnel on the Bacup to Facit branch line. As can be seen from the photograph of 176 New Line, the last house they occupied, this was a street of modest but well-built stone houses, well suited for a teacher and his young family.

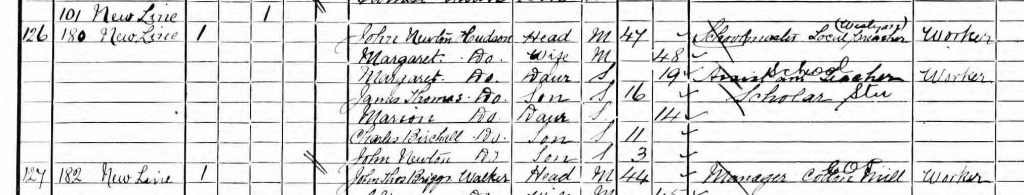

In the 1901 census they were living two doors down at 180 New Line and one further child had arrived, John Newton junior, then aged 3. The main revelation from this census in terms of our story, however, is that the now 20 year old Margaret was following in her father’s footsteps, listed as an ‘Assistant School Teacher’. It is not clear where she was teaching, and the teaching record on a later teacher’s registry entry (see below) makes no mention of this period, but maybe she was assisting her father at a local elementary (primary) school whilst gaining her teaching qualification.

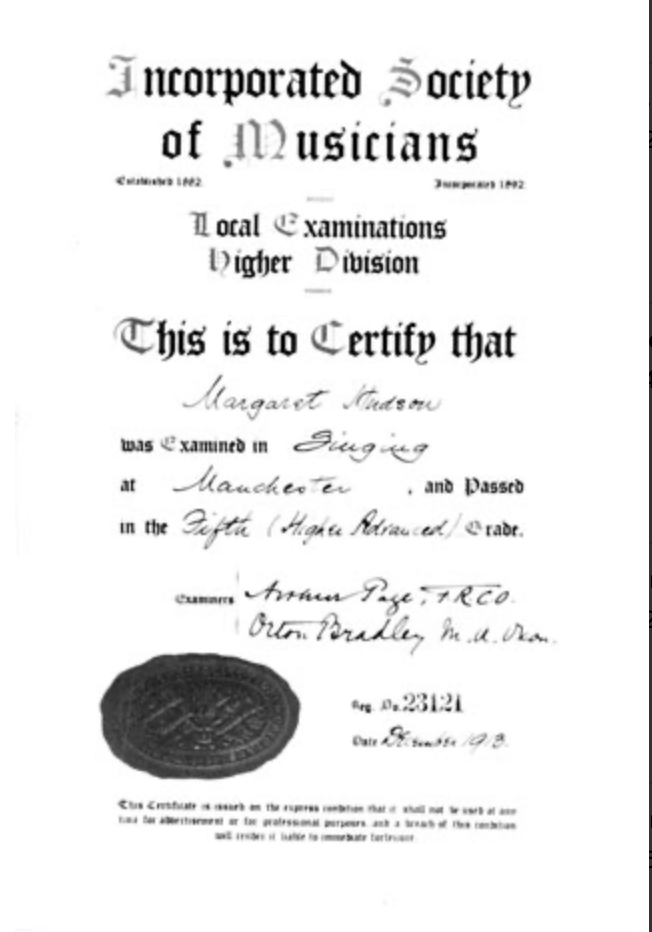

At the same time as she was training to be a teacher, she was also taking singing lessons, as is evidenced by the certificate (sadly undated) from the Incorporated Society of Musicians, to mark her achieving Grade 5 (Higher Advanced) in singing. The Incorporated Society of Musicians (now known as the Independent Society of Musicians) was set up to promote the importance of music and musicians following a public meeting in Manchester in 1882. What I have been unable to ascertain is whether she attended any formal establishment either for teacher training or singing, though a Day Training college for male trainer teachers had been set up in Manchester in 1890 followed in 1892 by one for female students, and feasibly Margaret might have been one of its early students.

However she was trained, she became a properly qualified in 1906 and by 1907 had been appointed Assistant Headmistress at Manchester Road Council Infants’ School, Droylsden, some distance from her home in Bacup. As we will see below, in both the 1911 and 1921 censuses she is shown as living in Bacup, but that would have involved a long journey every day by train and tram. Maybe as a single women (female teachers were not allowed to marry until 1919), she lived near her work during the week and went back to what she considered her home at weekends. What is clear from her first advertisement as a singing teacher, as we will see below, she gave an address close to her workplace, not her address in Bacup.

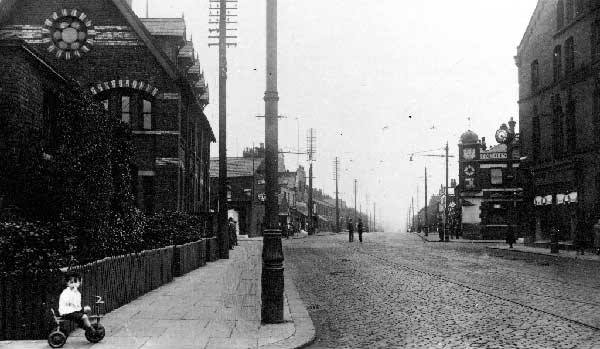

In 1907 Manchester Road council school was a brand new establishment, and maybe the boy on the tricycle in the 1910 photograph of the neighbourhood was one of its early pupils! It celebrated its centenary in 2007 and it still in existence today as Manchester Road Primary Academy.

Gratifyingly, Manchester Council’s ‘Greater Manchester Lives’ picture archive contains a number of photographs of Margaret Hudson at each of the three main schools at which she worked. What is remarkable about the first of the photographs is how much it has the look of my own infants’ school classroom in the early 1960s, over 50 years after this photograph was taken, with obedient children in serried ranks of wooden desks. The 26 year old Margaret looks on approvingly from the back. Was she a stern schoolmistress? We shall never know! Some of the teachers in the second photograph taken at Manchester Road look severe, but I do like the look of the dolls house to the right of the picture.

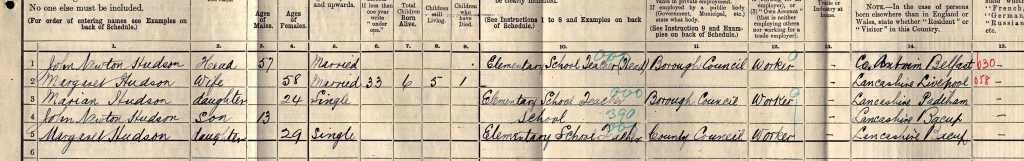

As I have already mentioned, the 1911 census still has her home address as Bacup, whether or not it was her permanent address. What the census does show is that her sister Marian was following in her father and sister’s footsteps and had also become an Elementary School Teacher.

I can’t help but be impressed by the commitment of the Hudson family across the two generations to education, supported no doubt by their Wesleyan Methodist faith. It was also around this time Margaret began to run alongside her duties as a teacher her other passion – music.

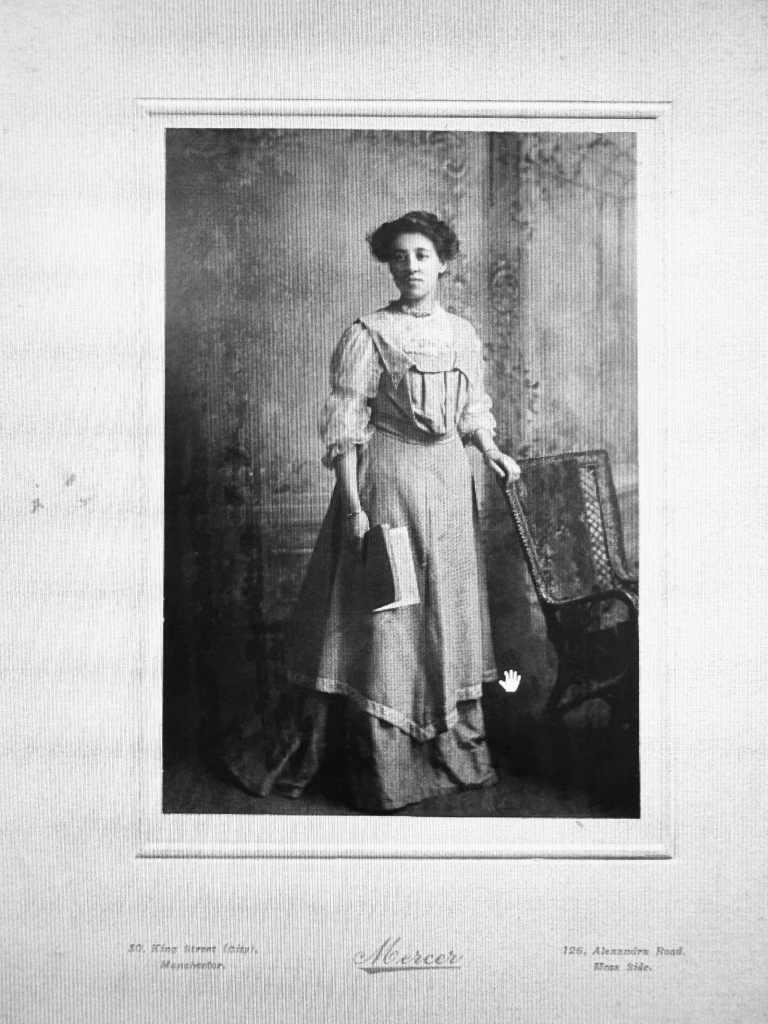

This passion manifested itself initially in three different ways. Firstly, she would take part in many of the competitive music festivals that were a feature of musical life throughout the North West at this time. Many of these festivals continue to this day. For example, I remember singing in my school motet group in the Chester Competitive Festival in the 1970s and the joy of winning the choral competition, and it still takes place every year, but overall in number and significance such festivals are sadly diminished. At this time they were so important that the Musical Times, for example, devoted many pages to reporting the results of the most recent festivals. For budding soloists such as Margaret they were important tests, such as here, where we see Margaret, who had just turned 30, winning first prize in the Contralto solo section at the 1911 Bury and District Musical Festival. Note the name of the adjudicator – R.H. Wilson, the then chorus master of the Hallé Choir. Might he have invited her to join the choir around this time? She must have seen a future for herself as a soloist as is shown by this portrait she had made. It is undated but judging from her appearance it must date from about this time, and must have served as a calling card for her as a singer. I wonder if that is a copy of an oratorio she is holding?

The second way in which her love for music manifested itself was therefore performance, and local North West newspapers over the next four decades include many reports of her various appearances. For example here in February 1914, just before the start of the First World War, we see her advertised as a featured guest of Broughton Gentlemen’s Glee Club, a couple of adverts below the latest Hallé concert to be conducted by Michael Balling and just above a concert by students of the Royal Manchester College of Music. Note the composition of the artists invited – a couple of classically trained singers, an elocutionist, an instrumentalist and a comedian. Such lineups were typical of the professional concert parties that used to tour the seaside pavilions of the country, famously described by J.B. Priestley in his novel The Good Companions.

The third manifestation of Margaret’s burgeoning musical career was her becoming a proper music teacher. Here we see a notice that she took out in the Stalybridge Reporter soon after the appearance at the Glee Club, advertising not just her services as a performer, but also as teacher of singing, piano and musical theory. It is clear that she very much considered herself, along with being a professional schoolteacher, a professional music teacher.

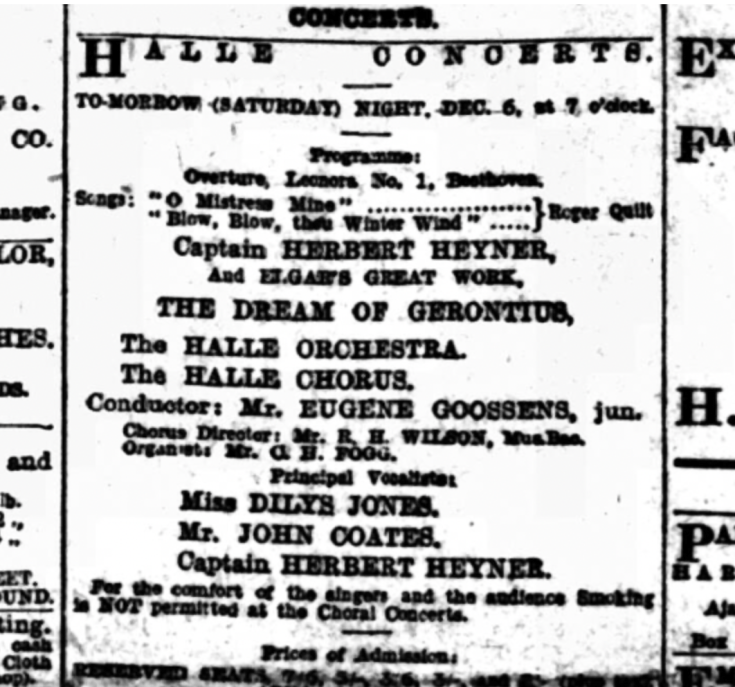

There is one aspect of her musical life for which she would not have been paid however, and that is her membership of the Hallé Choir, which has always been resolutely an amateur organisation. With her prowess as a soloist, it was probably inevitable that when the Hallé Orchestra came to perform Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius for the twelfth time in 1919 she would be asked to sing in the semi-chorus. The performance was to be conducted by Eugene Goossens, member of a formidable musical family that included his father Eugene senior, a Belgian conductor and violinist, and his brother and sister Leon and Sidonie, who both became internationally renowned soloists on the oboe and harp respectively.

You can see below how the semi-chorus members are listed in the Hallé Archive database. There are 23 of them, six to a part apart from the tenors (it was ever thus!).

The performance was well received by critics in both the Manchester Guardian and the Manchester Evening News, though the latter was not happy with the inclusion of three secular vocal pieces sung by Herbert Heyner before the main event which he found a trifle distracting. He felt that for the conductor, the performance of Gerontius was ‘a decided triumph’, and that ‘his grip on the large choral and instrumental forces never relaxed’, and he had special praise for tenor John Coates as Gerontius. As for the choir:

The chorus singing was everywhere splendid in tone and attack, and attained a high level of general expressiveness, in spite of an occasional lapse in a few delicate moments of nuance indicated by the composer.

From a review in the Manchester Evening News, 8th December 1919 (British Newspaper Archive)

Granville Hill’s review in the Guardian was also generally praising of the choir, and whilst the semi-chorus are picked up for a degree of criticism, thankfully it wasn’t criticism of Margaret and her fellow altos:

In the various forms of “Praise to the Holiest in the Height” there was an elasticity and smoothness in the choir singing beyond the grace of other years. The intonation of the semi-chorus in the highest notes was not always above reproach

From a review by Granville Hill in the Manchester Guardian, 8th December 1919 (Guardian Archive)

Margaret’s Teachers Registration Council certificate shows that soon after the Gerontius performance she changed job when, at the age of 40 in 1921, she became a Head Teacher in her own right for the first time at Hooley Hill Wesleyan School in Audenshaw. The Teachers Registration Council ran from 1914 to 1948 and was the body responsible for maintaining records of all qualified teachers. Note that this certificate therefore shows not only her qualification for teaching in schools, the Board of Education Certificate, but that for teaching singing from the Royal College of Music. This 1921 appointment again shows her connection with Methodism.

A Wesleyan Methodist Society was first formed in Hooley Hill in 1786. A purpose-built chapel and Sunday school were built in 1806, followed by another new school in 1855. Hooley Hill Wesleyan School, the school where Margaret taught, opened 1901 and closed in 1950.

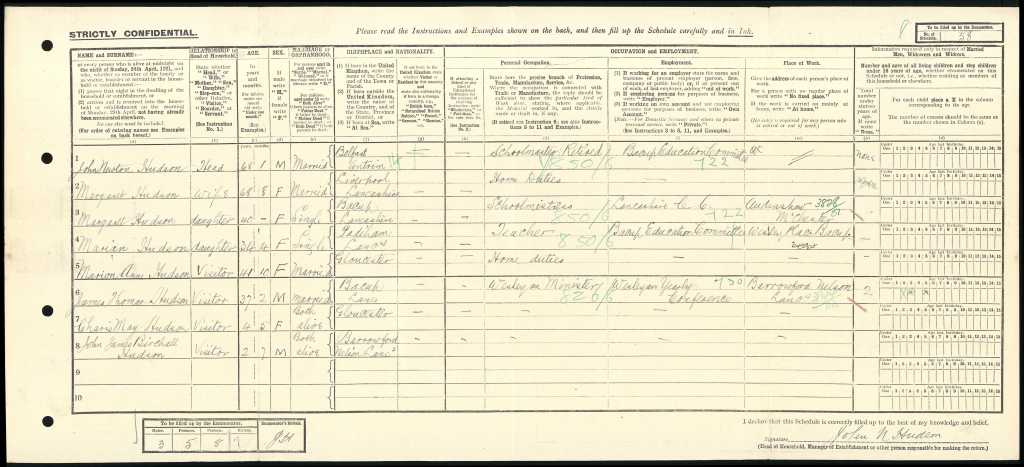

Another Wesleyan connection appears in the 1921 census. As in the 1911 census Margaret appears in the entry for the family home in Bacup, and she is shown as working as a teacher for Lancashire County Council in Audenshaw. Her sister Marian also appears, again as a teacher, but her school must have been local as she is shown as working for Bacup Education Committee. Also staying with them as a visitor, however, is Margaret’s younger brother John Thomas Hudson, his wife Marion and their two young children, and he is described as a Wesleyan Minister in Barrowford, Nelson, Lancashire.

Once again we are really lucky to have photographs of Margaret in her role as Headmistress in the Greater Manchester Lives archive. Here we see a very well-behaved group of young children pictured in May 1921 with Margaret looking on proprietorially from one side of the group and a slightly more harassed and impossibly young looking fellow teacher looking at the camera from the other side.

Margaret only appears to have been in charge for one school year, and in 1922 she moved to be Head Teacher at Denton Central Council Primary School, judging by pictures a much bigger establishment. It had been notable in that during the First World War it had been converted into a military hospital and it would later be converted to a first aid station during the Second World War. In the 2000s it closed as a primary school and is being reopened as a special needs school. The photograph below accompanied a Manchester Evening News report on its conversion in 2025.

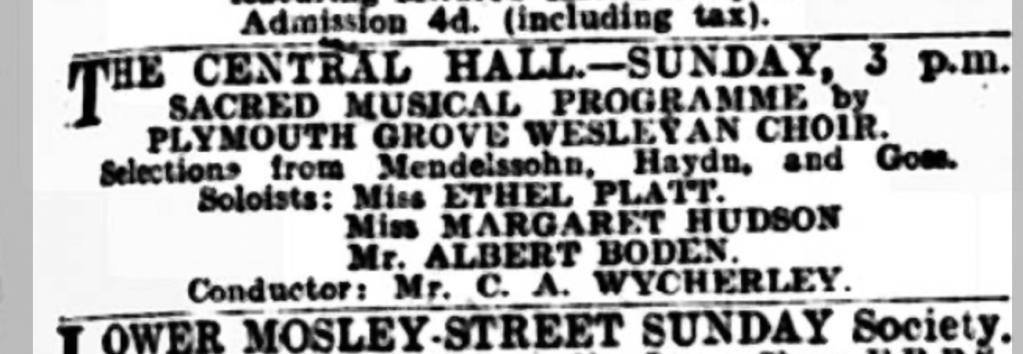

One hundred years earlier, in 1923, Margaret was still pursuing an active singing career alongside her teaching duties. In November 1923 the Manchester Evening News was advertising a concert of sacred music in the Methodist Central Hall in Manchester by the Plymouth Grove Wesleyan Choir (note the double Methodist connection), and among the featured soloists was ‘Miss Margaret Hudson’.

Margaret was to remain Head Teacher at Denton for nearly 20 years, retiring in 1941 to devote herself exclusively to teaching music, of which more below. Sadly there are no pictures of her with her pupils but Greater Manchester Lives does have one photograph of her with her staff which, judging by the hairstyles, was taken sometime in the late 1920s. What seems to be clear from the general sense of order is that she ran a tight ship.

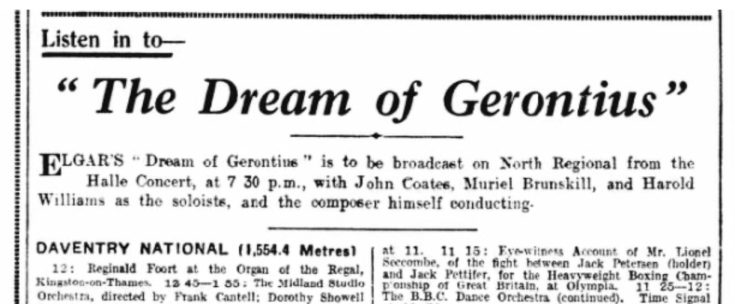

January 26th, 1933 saw a second appearance in the semi-chorus in a performance of Gerontius, and this one had added piquancy in that it was conducted by the composer himself, Sir Edward Elgar. What’s more it was to be broadcast across the regions by the BBC, which was big news in a way that is unimaginable today, evidenced by the Lancashire Evening Post making it their pick of the day in their radio column.

Elgar was to die the following year and so his appearance was very much seen as that of a treasured elder statesman nearing the end of his days. This is exemplified by the opening paragraph of Granville Hall’s review the day after the concert in the Manchester Guardian:

The concert last night was conducted by Sir Edward Elgar, and before his music began and at its close the audience rose to acclaim him with such long-continued applause as is usually reserved in these days for favourite film stars and musical comedy actresses. This spontaneous tribute of admiration and affection for the greatest British composer was a heartening sign that we do really appreciate the unique figure Sir Edward is and what he has done to raise musical art in England to a level on which it can take its place side by side with the best contemporary music of Europe.’

From a review by Granville Hall in the Manchester Guardian, 27th January, 1933

There were signs of age in Elgar’s conducting. Hall writes that he conducted the whole piece seated and that ‘it was obvious that at times the absence of a beat that is commanding as well as alert meant the slight diminishing of effect in the most tempestuous parts of the music.’ Hall made special mention of the choir who, ‘except for a moment or two in the Chorus of Demons’ were ‘clear and sonorous’, rising to ‘splendid heights when there was most need of the conviction of religious exaltation.’

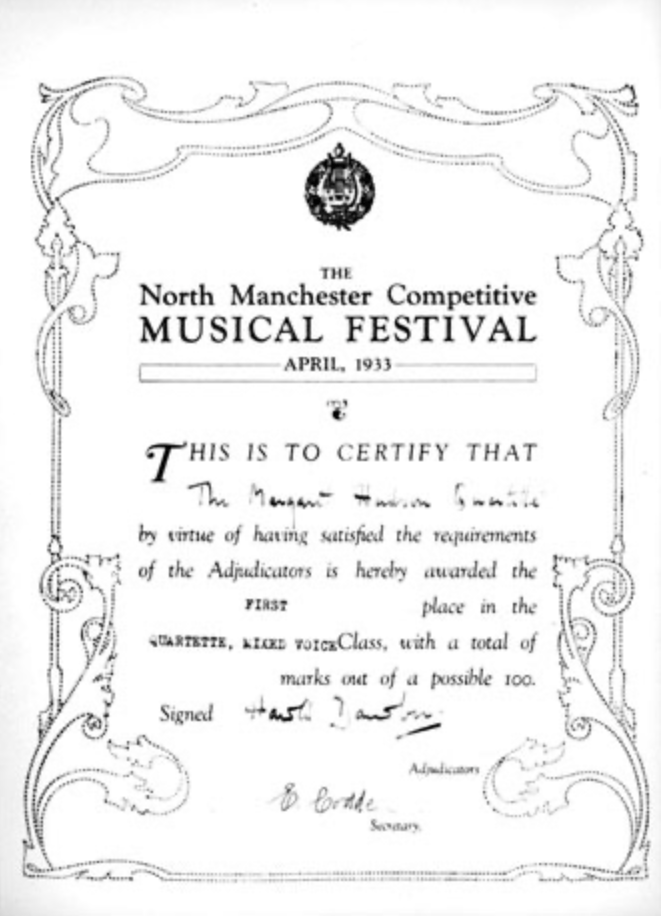

We shall never know Margaret felt about performing under Elgar, but she was to perform once more in the Gerontius semi-chorus, in 1935 under Malcolm Sargent. Through the 1930s her extra-mural musical career continued apace, especially with the ‘Margaret Hudson Quartette’, a group that she had put together both to compete in festivals and to appear in a concert setting. In April 1933 they won first prize in the ‘Quartette, Mixed Voice’ class in the North Manchester Competitive Musical Festival. Note again the Hallé connection – three months after the performance of Gerontius in the Free Trade Hall the adjudicator was Harold Dawber who ten years previously had taken over from R.H. Wilson as chorus master of the Hallé Choir.

Four years later, the Manchester City News was reporting on a ‘delightful concert party’ in Milton Hall on Deansgate in Manchester given by ‘the “Margaret Hudson” Prize Quartette and Concert Party’. There were actually six of them, with Jo Watterson (soprano), Margaret herself (contralto), Lawrence Corrigan (tenor) and John Marsh (bass) singing to May Brierley’s piano accompaniment, and Rose Walters listed as an ‘entertainer’ and described by the reviewer as a ‘most versatile entertainer, her display of dramatic, serious and humorous items proclaiming an all-round knowledge of her art.’ The reviewer enjoyed the singing as well as the humour: ‘the members of the quartette are all talented vocalists, and in their concerted work show a nice blend of tone’, such as in Margaret and John Marsh’s duet rendition of an old Scottish folk song dating back to the early 19th century, ‘Hunting Tower’. It’s noticeable that in the quartette Margaret was mirroring the type of concert party ensemble that she had appeared in 25 years previously.

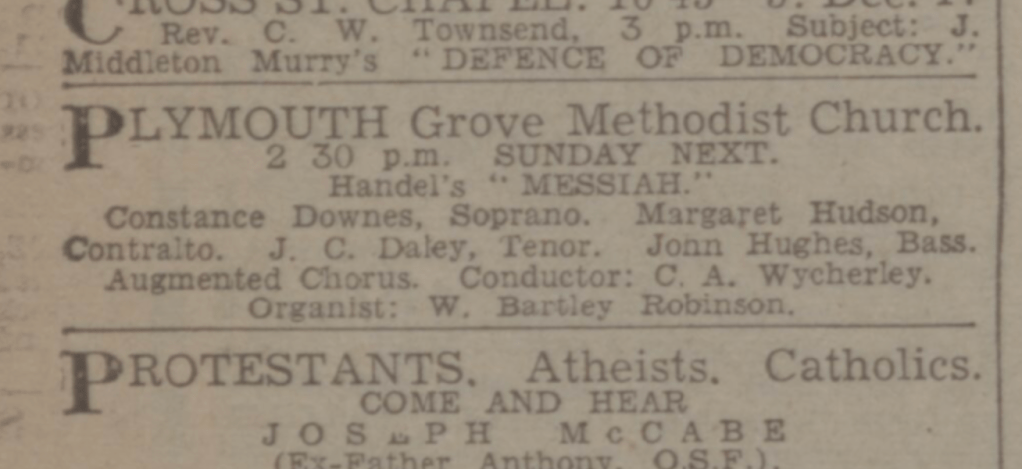

Fast approaching her 60th year Margaret was also still in demand as a soloist. In December 1938 there was an advert in the Manchester Evening News for a performance of Handel’s Messiah featuring Margaret as the alto soloist. It was conducted by C.A. Wycherley, who had conducted Margaret’s Central Hall concert 15 years previously. The concert was to take place at Plymouth Grove Wesleyan Methodist Church, a grand building now sadly demolished but only a stone’s throw from what was in the 19th century the residence of another formidable Manchester woman with Hallé connections, the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell. It would be one of the last opportunities to perform Messiah in peacetime for seven years, but sadly no report exists of how successful it was or how well Margaret sang.

The other side of the Second World War saw Margaret still competing in competitive festivals, though in the Alderley Edge Musical Festival in 1946 she, along with Hilda Hall, Joseph Wright and Clifford Bottomley, only achieved 2nd place in the Vocal Ensemble category.

1951 saw her 70th birthday, and in a private collection of photographs on the Ancestry website I found a delightful picture of her on her birthday looking remarkably happy and content. She was far from retired, however.

Through the 1940s, 1950s and into the 1960s Margaret was regularly putting notices in the Manchester Evening News advertising her services as a singing and piano tutor, just as she had done in the Stalybridge Advertiser back in 1914. The last of these I was able to find dated from 1968, the year of the Beatles’ White Album, the Paris Riots and the Grosvenor Park anti-war demonstration, and one year before a man first walked on the moon. Margaret would have been two months short of her 87th birthday, still going strong and living in the relative luxury of a substantial house in Victoria Park, relative that is to her beginnings in New Line, Bacup.

She died towards the end of 1971 at the age of 90 having brought enlightenment to numerous generations of infant schoolchildren for the first 40 years of the century and having lived and breathed music for the best part of 70 years. She may not be remembered in the same way as the great soloists with whom she sang in the Hallé Choir, but in her own quiet way she enriched the musical life of Manchester in equal measure.

In the next blog I will tell the story of Ernest Houghey, who sang in the very first performance of Gerontius in 1903 and progressed from the streets of Liverpool, via the Hallé Choir and an attempted career in Grand Opera with Thomas Beecham to riches as a property developer in Sussex and a final resting place far away in Southern California.

References

The research tools used were:

Ancestry ancestry.co.uk

British Newspaper Archive britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Lancashire Family History and Heraldry Society www.lfhhs.org.uk

Guardian Archive via Manchester Libraries

Hallé Archive

Greater Manchester Lives picture archive www.gmlives.org.uk

Google Street View www.google.com/maps

Manchester History Revisited Facebook Group

Tameside Council Facebook Group

University of London General Register Part 3 (1901) https://archives.libraries.london.ac.uk/resources/general_register_part_3.pdf

Extra information:

George Lythgoe, ‘New special educational needs school will be built in Greater Manchester town’, Manchester Evening News, 21st August 2025 https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/new-special-educational-needs-school-32316679

Jenny Keating, ‘Teacher training – up to the 1960s’, History in Education Project – Institute of Historical Research (University of London, December 2010)

Helen Patrick. “From Cross to CATE: The Universities and Teacher Education over the Past Century.” Oxford Review of Education, vol. 12, no. 3, 1986, pp. 243–61.

Leave a comment