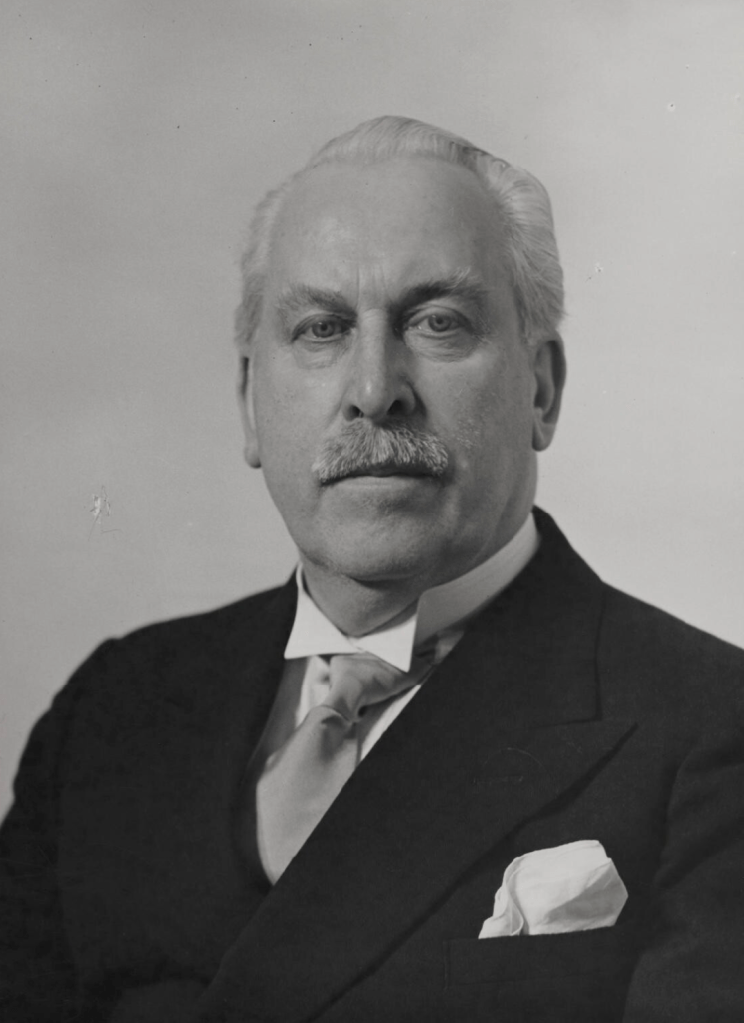

Sir Arthur Bliss (first appearance with choir 1956, knighted 1950)

We pick up our survey of Hallé Choir conducting knights in the 1950s with a composer/conductor who at the time held the hallowed position of Master of the Queen’s Music, the first holder of the role to serve exclusively under the new monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. Bliss was from the generation of Royal College of Music-trained composers, along with notable musicians such as Herbert Howells, Ivor Gurney, Arthur Benjamin, and Eugene Goossens, that immediately succeeded the generation that included Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. Both of these generations were deeply affected by the First World War. Vaughan Williams served as a stretcher bearer on the Western Front, an experience which deeply affected his compositions in the immediate aftermath of the conflict. Likewise Bliss served on the front line through the duration of the war and took part in at least two major battles.

Bliss’s experiences also fed into his post-war compositions. Though he is perhaps best known today for his incidental music for Alexander Korda’s film adaptation of H.G. Wells’ Things to Come and a number of ballets for Ninette de Valois and what would become the Royal Ballet, there is one work in particular that directly addresses his wartime experiences, namely his 1930 work for narrator, chorus and orchestra, Morning Heroes. It is a fascinating work in the way in which it prefigures two later works that achieved greater popular fame but on which it may well have been an influence, namely Vaughan Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem of 1936 and Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, written for the opening of the new Coventry Cathedral in 1962. Like Morning Heroes, Dona Nobis Pacem is a compendium piece using a variety of literary sources, including a number of poems by the American poet Walt Whitman, excerpts from whose The Mystic Trumpeter and Drumtaps featured prominently in Morning Heroes. Britten’s War Requiem weaves the words of the Latin Requiem Mass around the First World War poetry of Wilfred Owen, and Morning Heroes similarly uses Owen’s poem Spring Offensive. Britten’s work is dedicated to friends who had died in action during the Second World War, but Bliss’s is dedicated more personally to his brother Francis Kennard Bliss, killed in action in September 1916 ‘and all other comrades killed in battle.’

The work itself traces a battle through from dawn to a battle and its fearful aftermath with the climax being a setting of Robert Nichols’ poem Dawn on the Somme, deeply personal in that it was in this battle that Bliss was wounded and his brother killed. In his autobiography Bliss wrote about a recurring nightmare about the war that afflicted him through the 1920s and the cathartic effect that writing Morning Heroes had – after its first performance the nightmares disappeared.

The work was commissioned by the Norfolk and Norwich Festival of 1930 but despite what would have been distinct resonances to a contemporary audience it took a further eleven years and another conflict for it to receive its first Hallé performance, in February 1941 with Malcom Sargent conducting. As such it was one of the rare Hallé Choir performances during the Second World War that wasn’t a performance of Messiah. A further Hallé performance took place in 1950 with the Hallé Choir’s choral director Herbert Bardgett conducting, before Bliss himself was invited to conduct the work in December 1956.

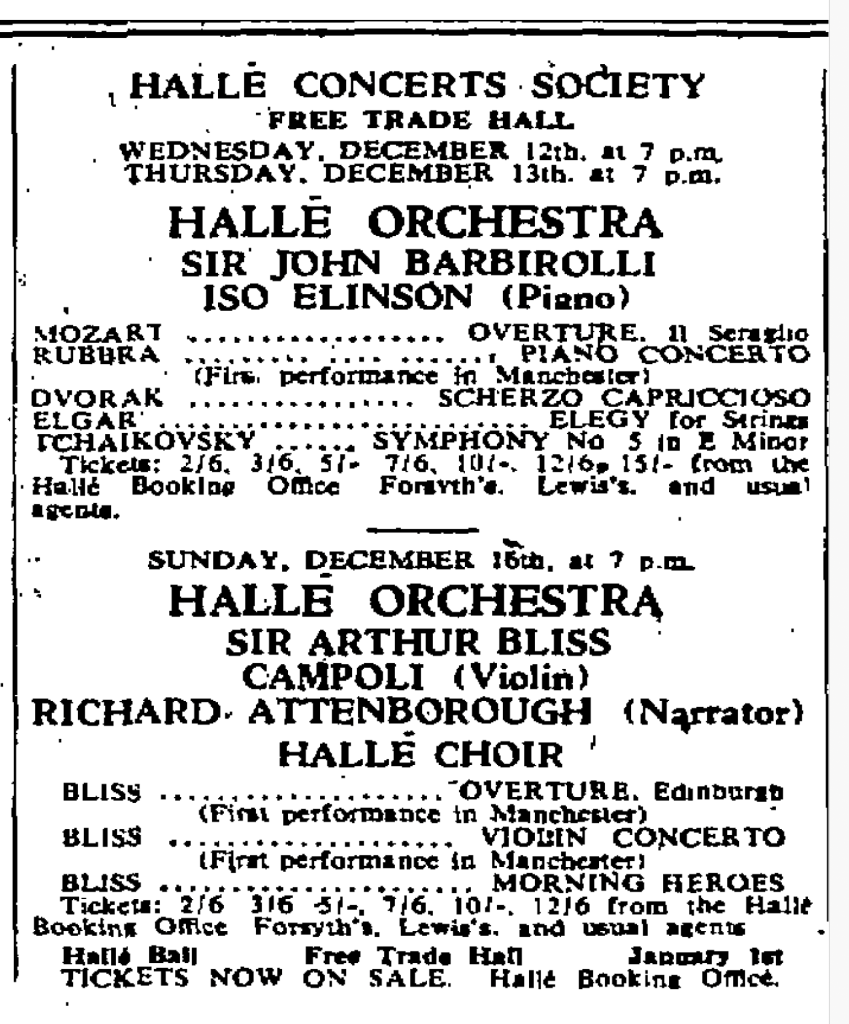

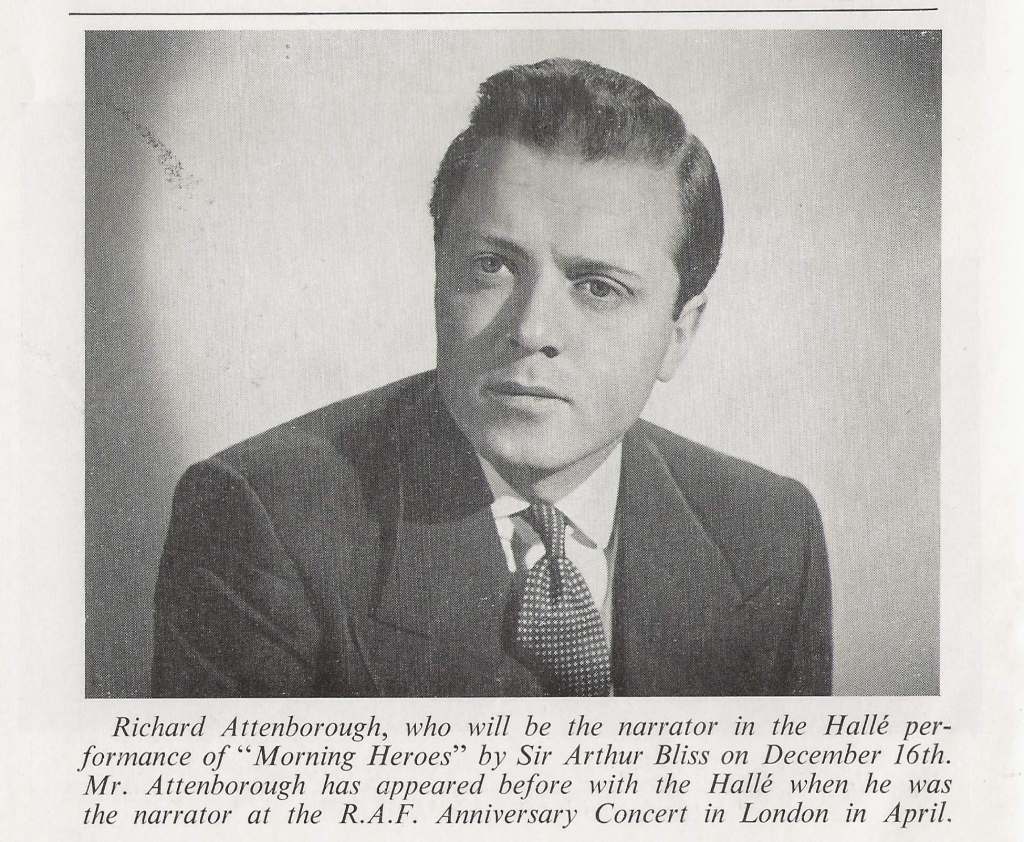

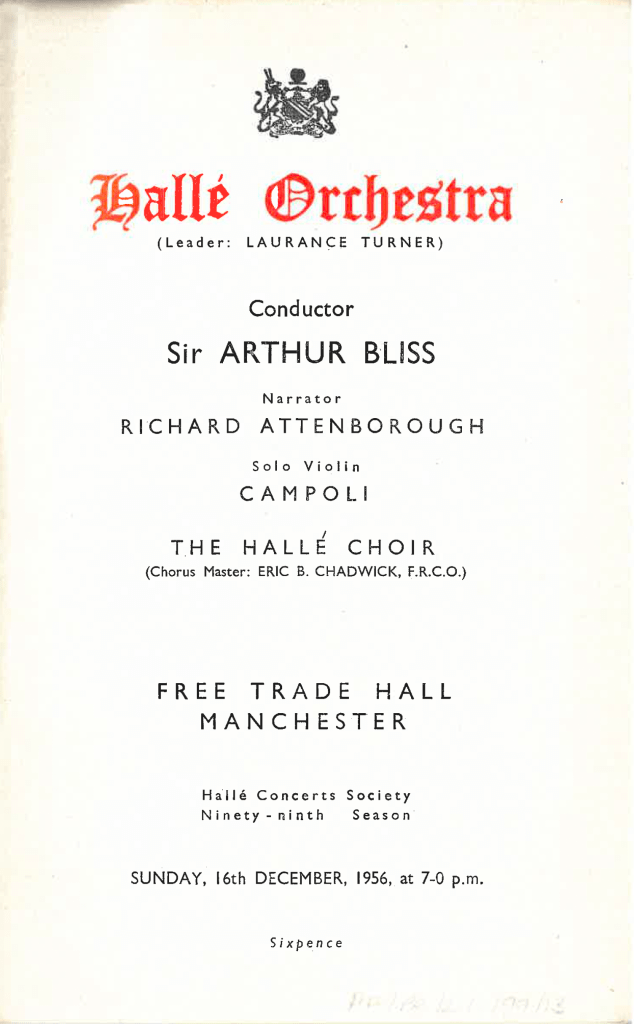

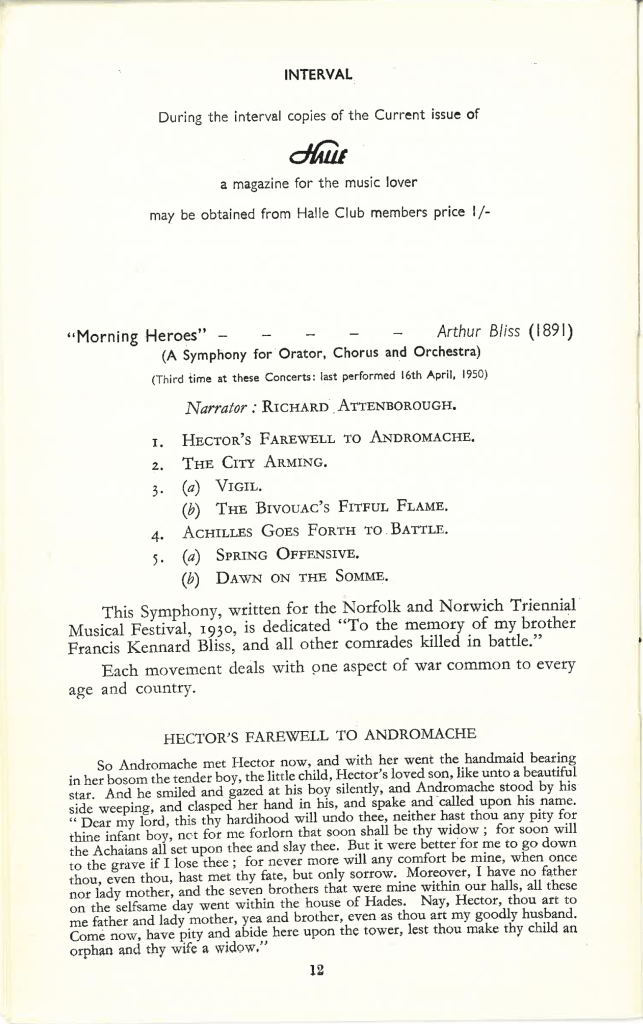

A crucial element of the work is the narrator and indeed the work begins with a lengthy spoken extract from Homer’s Iliad in which Achilles prepares for his bloody battle with Hector at a decisive point in the Trojan War. The Hallé’s performances certainly attracted acting royalty for its performances of Morning Heroes. The 1941 performance had Sir John Gielgud narrating and the 1950 featured his great acting rival Sir Ralph Richardson. For the 1956 performance the Hallé went to a later generation of actor in the shape of Richard Attenborough. Attenborough’s first big film role had been as a young stoker in Noel Coward’s classic wartime drama In Which We Serve in 1942. Though he was called up by the RAF the year after and trained as a pilot, he never saw active service as he was deemed to more useful as an actor in the RAF’s Film Unit. By 1956 he was a household name as an actor from appearances in films such as Brighton Rock and London Belongs to Me and plays such as The Mousetrap (he was the original detective sergeant in this epically long-running drama, as noted in the recent comedy drama film See How They Run). Though he had already appeared with the Hallé in an RAF anniversary concert (as featured in a previous blog), as can be seen from the above photograph in the Hallé magazine his appearance was something of an event.

Given this build up it would be nice to report that the choir’s performance of Morning Heroes was a critical success. Sadly, that wasn’t the case, at least as far as the Manchester Guardian was concerned. Part of may be the fault of the work itself, which while it is obviously deeply personal for the composer doesn’t have the depth and colour of the Vaughan Williams and Britten works. Whilst the spoken word passages are effective, especially Owen’s Spring Offensive, set for just timpani and narrator, the choral passages too often simply alternate between pathos and bombast depending on the mood of the poem being set. Reading Colin Mason’s review of the concert in the Guardian, he seems to share my opinion, though as a supposedly dispassionate reviewer he appears here to be reviewing the work rather than the performance, a trait that you will see below reappears a year later:

“Dawn on the Somme,” ‘Vigil” and “The Bivouac’s Flame,” all provide examples of banal and unimaginative adherence in the music to the natural prose or verse rhythm of the text. The composer is at his best in this respect in the more martial parts. But his verbal unsubtlety is only part of a more general literary and aesthetic failing…

From a review by Colin Mason in the Manchester Guardian, December 17th, 1956

Richard Attenborough is not spared criticism. Though Mason describes the setting of Spring Offensive as ‘the composer’s finest poetic and dramatic stroke’, he feels ‘it was almost wrecked here… by Richard Attenborough, who in trying to find the tone of low tension and relaxation required for the first two stanzas, delivered them like a B.B.C. announcer.’

Mason’s final comments, however, may provide the clue as to why, when Dona Nobis Pacem and War Requiem continue to find a place in concert programming, Morning Heroes does not, in that it doesn’t chime well with modern attitudes towards. It is similar in this regard to Elgar’s The Spirit of England, though the musical excellence of that particular work has ensured it does at least get the occasional performance. In the nearly 70 years since that 1956 performance Morning Heroes has yet to receive a further performance, and indeed Bliss never again conducted the Hallé. Here is Mason’s summation:

Bliss’s general treatment of the theme of war belongs in the age before 1914. He deals with the glory of war, the tears of mothers, adventure, thoughts of home in the trenches, heroism and peace through war, voicing no moral protest against war, nor seeming to have considered the futility of it. Such notions and sentiments are irrecoverably remote from us to-day and if we respond to the work at all it is to go home not elated by it but depressed by the pessimistic thoughts to which it inevitably leads us.

Colin Mason

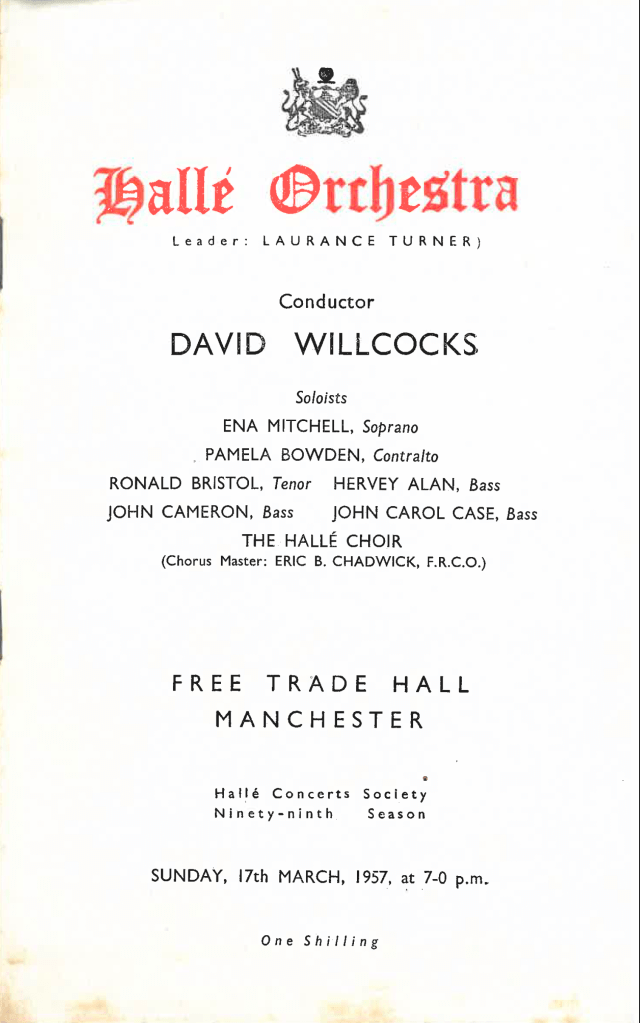

Sir David Willcocks (first appearance with choir 1957, knighted 1977)

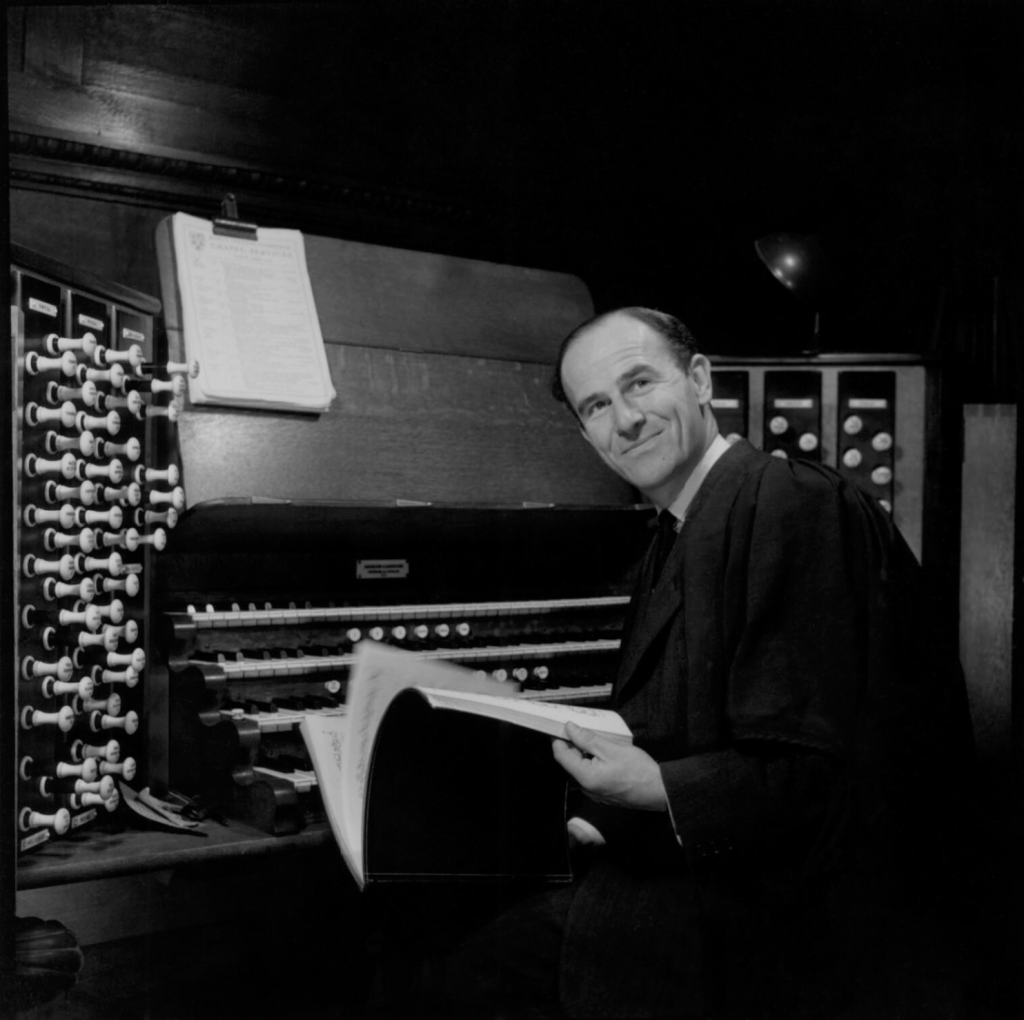

Our next conducting knight is David Willcocks who first conducted the choir in 1957 at the age of 38, but continued to be active well into his 90s and only passed away relatively recently in 2015. Born in Cornwall in 1919 he gained an organ scholarship at King’s College, Cambridge before serving in the Second World War (he took part in the Normandy campaign in 1944). It was as an organist and choirmaster at Salisbury and Worcester Cathedrals that he began his musical career, before returning to King’s College in 1957 to take up the post of organist and director of music. During his 17 years at the college he achieved national and international fame, through his stewardship of the famous college Nine Lessons and Carols service, through the many recordings he made with the choir and through his editorship along with Reginald Jacques and John Rutter of the Carols for Choirs series of music books. King’s College became synonymous with the English choral tradition, a status it arguably still holds today, largely as a result of his legacy. As the composer John Rutter wrote of Willcocks in a tribute in his centenary year, ‘Quite simply, that choir made choirs everywhere else sing better.’

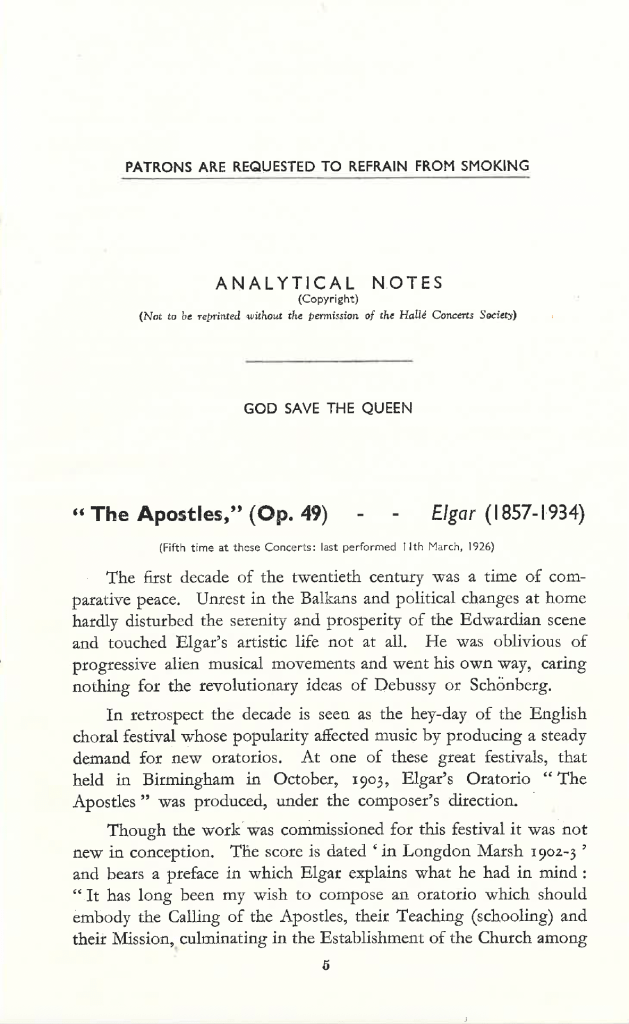

Although at Cambridge he worked with relatively small forces, he was never afraid to work at a larger scale, as evidenced by his becoming director of the Bach Choir in 1960, one of the largest independent symphonic choruses in the country, and by the many ‘Come and Sing’ events he would direct at the Royal Albert Hall where the number of participating singers would often in the thousands. Crucially, in his capacity as choirmaster at Worcester Cathedral, he had also from 1950 onwards been involved with the Three Choirs Festival both preparing choirs and conducting performances. Indeed, 1950 saw him conduct Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius at the festival. Therefore, while it might seen slightly surprising that a humble cathedral choirmaster should be asked just before taking the job that made his name to conduct the Hallé orchestra and choir in a performance of Elgar’s most monumental oratorio, The Apostles, in retrospect it made absolute sense.

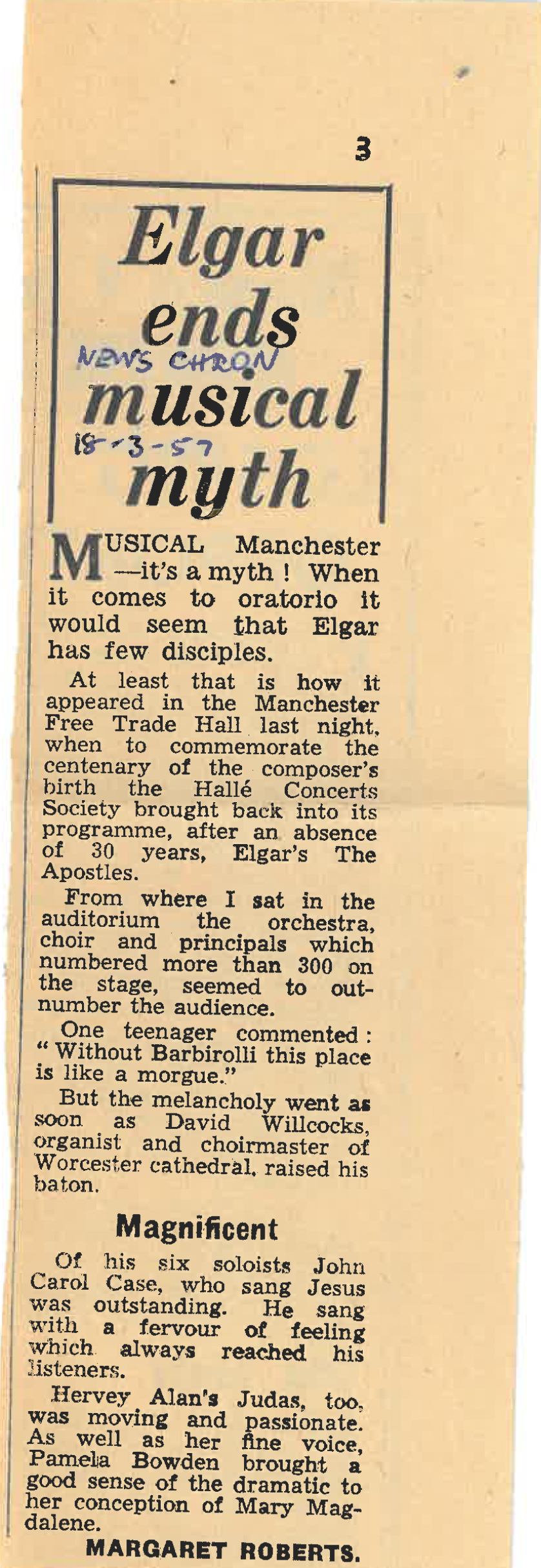

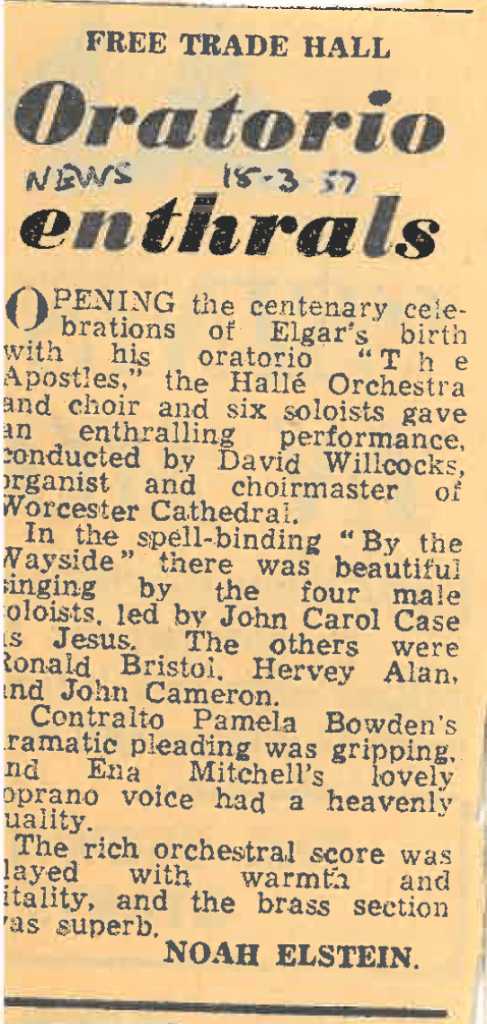

It was a delight to find that the copy of the programme for the concert in the Hallé Archive also included three clippings of reviews of the concert and as you can see I’ve included them in the blog. They indicate a degree of enthusiasm for the music on the part of the programme buyer, which, judging by a comment in the News Chronicle review may not have conveyed itself in advance to the concert-going public of Manchester, who do not appear to have turned up in large numbers: ‘From where I sat in the auditorium the orchestra, choir and principals which numbered more than 300 on the stage, seemed to outnumber the audience.’

However, whilst Margaret Roberts was dismayed by the audience size, she was not dismayed by the performance, writing that ‘the melancholy went as soon as David Willcocks, organist and choirmaster of Worcester Cathedral, raised his baton.’

Noah Elstein, writing in the Manchester Evening News, was of like mind, calling it ‘an enthralling performance’, with a special mention for the By The Wayside section of the oratorio that had formed the choir’s first commercial recording 30 years earlier in 1927 (as described in this blog).

As a counterpoint, writing in the Manchester Guardian Colin Mason used much of the same style of critical vitriol that he had used when reviewing Morning Heroes a year earlier. He committed what in my humble opinion is a cardinal reviewing sin in that he spent much more time critiquing the work than he did the performance, a sin that was repeated many years later by a reviewer from the same esteemed paper in a review of the choir’s Proms performance of The Apostles in 2012. After commenting on the size of the audience at the performance ‘which looked worse attended than any Hallé previous concert this season’, he proceeded to lay the blame for this on the quality of the work and spent two thirds of the review explaining why he did not like The Apostles, such as where he writes that ‘Part 1 of “The Apostles” is in truth an hour of almost unmitigated dullness, relieved only by the occasional recurrences of one or two striking musical motives.’ Later he writes about how some of Elgar’s ‘attempts at dramatisation’ are ‘naive, rarely effective’ and ‘sometimes almost comical.’

There is certainly a place for a critical analysis of a work in a review, especially where the work is new or a rarity, but for a 50 year old work that, though not performed as often as Gerontius and The Kingdom, was still an established part of the oratorio repertoire, Mason’s comments do seem excessive, maybe even more so than in his review of Morning Heroes given that work’s relative newness. When he finally gets to review the actual performance in the final paragraph, it is difficult to tell, given the enthusiasm of the two other reviews, if he is being hindered by his opinion of the piece: ‘The work did not, it must be said, enjoy the liveliest possible performance from David Willcocks, although as organist and choirmaster of Worcester Cathedral he should have his heart in it as deeply as anybody. The Hallé Choir and Orchestra performed capably, but understandably did not seem to find much inspiration in the work.’ Mason may have been right about the performance, but this is a case in point of how one should always look at the context of any review, be it good or bad.

Poor attendance and Guardian reviews notwithstanding, the Hallé Concerts Society still felt confident seven years later of engaging Willcocks to conduct the second Hallé Choir performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem in November 1964 (the first performance had been a year earlier conducted by Meredith Davies, who had conducted the chamber orchestra in the first performance of the piece in 1962). The performance featured the choir alongside the boys of Chetham’s School and amongst the soloists was Heather Harper, who had sung in the Coventry premiere. Following this, as far as the Hallé was concerned, Willcocks became a specialist Messiah conductor, conducting the orchestra and the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus in performances in 1969, 1971, 1974 and 1979, but the orchestra and the Hallé Choir only once, in 1974.

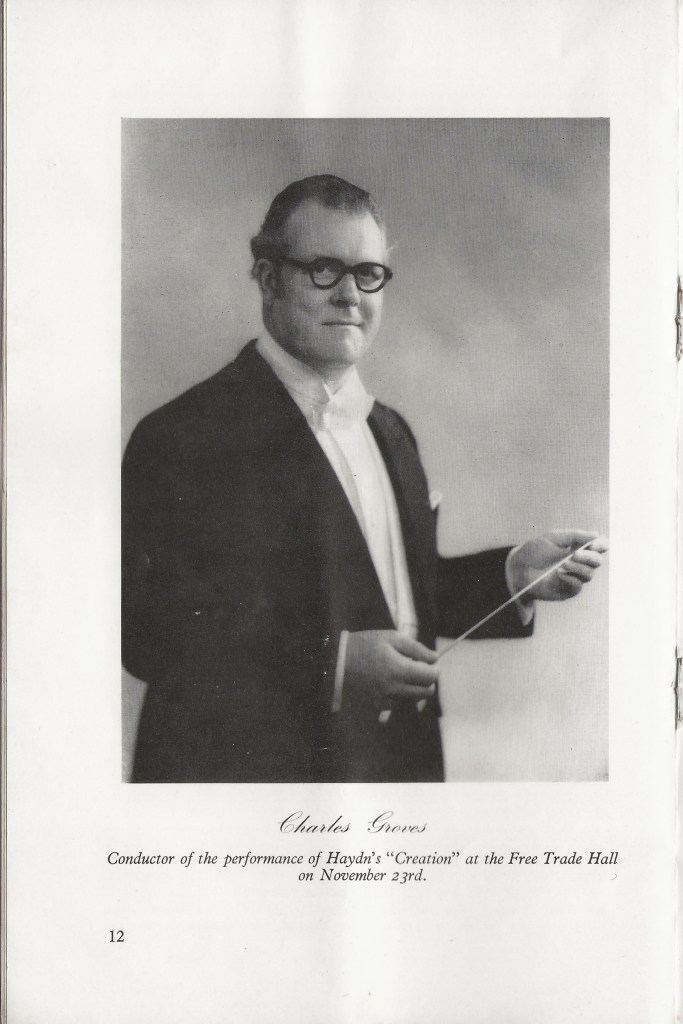

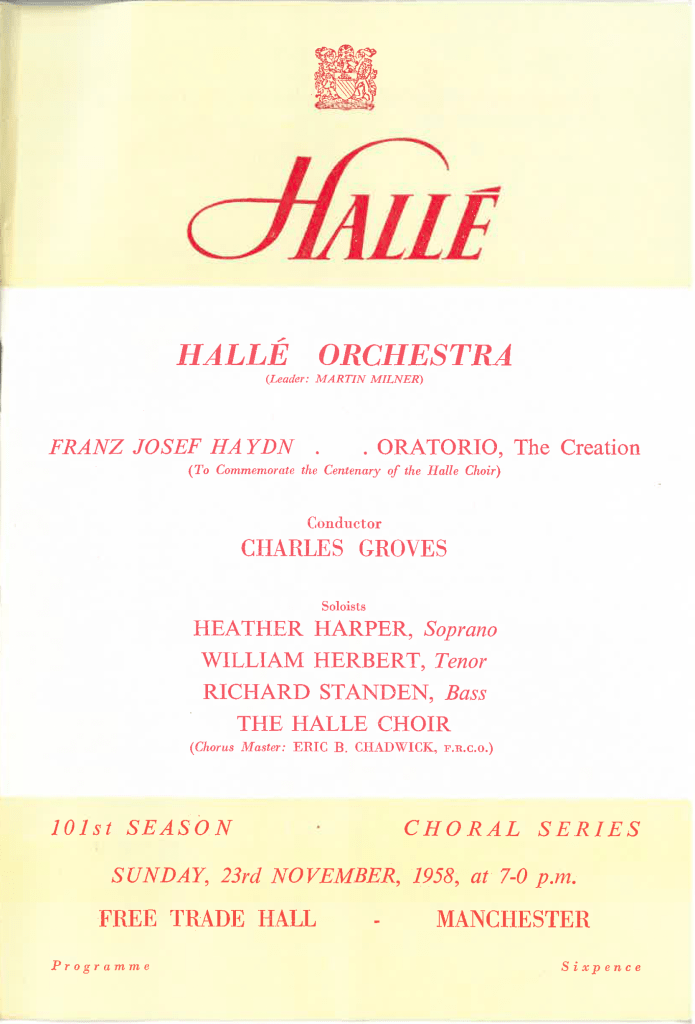

Sir Charles Groves (first appearance with choir 1958, knighted 1973)

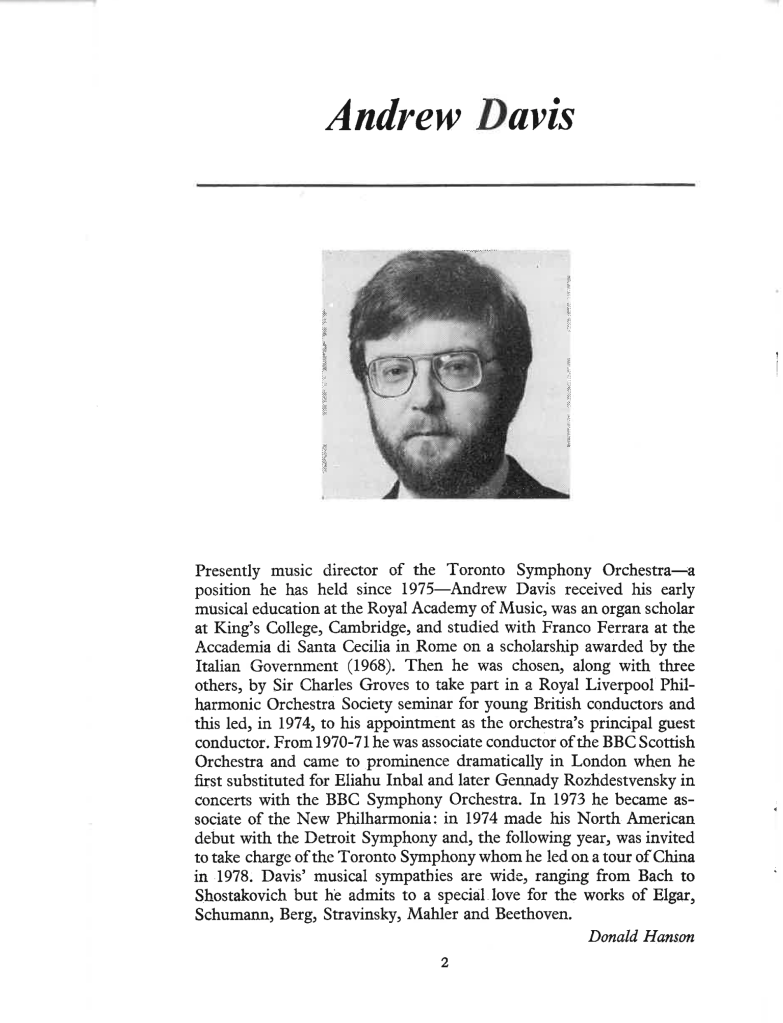

Though born in London in 1915, Charles Groves, who first conducted the Hallé Choir in 1958, had long standing links to the North of England, serving as chief conductor of the BBC Northern Symphony from 1944 to 1951 and of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra from 1963 to 1977. Like David Willcocks he was also well steeped in English choral music, having been in St Paul’s Cathedral choir as a boy and later, after studying at the Royal College of Music, serving as chorus master for the BBC opera unit. Whilst in Liverpool he instituted a series of seminars for aspiring conductors, attendees of which included Mark Elder, Andrew Davis and John Eliot Gardiner. He was particular passionate about British music, from established figures such as Elgar and Vaughan Williams through to young firebrands such as Peter Maxwell Davies, and was fastidious in preparing any music that he approached.

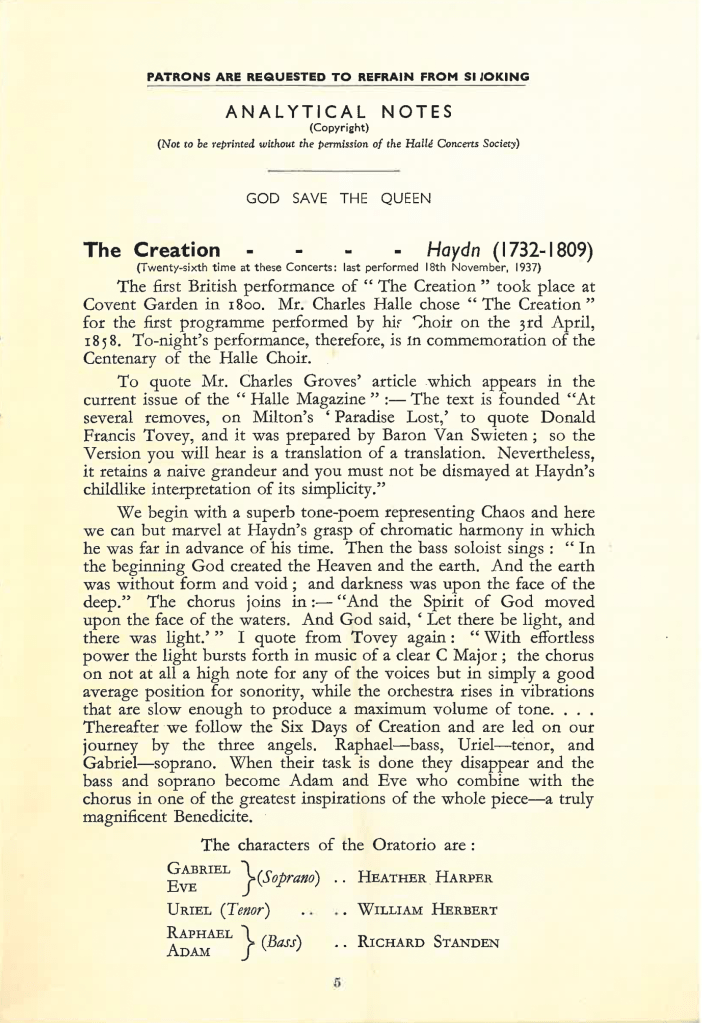

This fastidious method is exemplified by the way he prepared for his first concert with the Hallé Choir, a performance of Haydn’s beloved oratorio The Creation in November 1958. His approach is outlined in an article he wrote for the November 1958 issue of Hallé magazine. After a century or more’s worth of performances of works from the Classical and Romantic repertoire had moved performance practices some distance from those originally conceived by the composers, there was at around this time the beginnings of a movement back to historically informed authentic performances of these works, led in the case of Haydn by the American scholar H.C. Robbins-Landon, who Groves name checks in his article. Groves writes that he is ‘on the side of the angels as far as the modern realisation of classical music is concerned’, and that ‘it is not high-falutin’ to wish to hear Messiah with Handel’s original instrumentation and a moderately sized choir.’ He is of no doubt that ‘the 19th century approach to 18th century composers was completely wrong.’ These ideas obviously took off through the 1980s and 1990s with the rise of orchestras and ensembles using period instruments and authentic performing practices, but in 1958 this was very new thinking.

Groves talked about how the new scholarship might inform his performance of The Creation. In the end his decision was to leave things much as they were, but at least he was thinking about it and rationalising his decision:

You will say, therefore, that for our performance of The Creation on November 23rd I should reduce the Hallé Choir to fifty or sixty voices. Well, I am not going to do so because Haydn has provided an orchestra of Beethoven proportions and if the singers exercise tonal discretion a good balance will be achieved. Haydn was more lavish, too, with his dynamic instructions than most of his contemporaries and his intentions may be realised more nearly under modern conditions than Bach’s or Handel’s.

Charles Groves writing in Hallé Magazine, November 1958

Readers may remember that in a previous blog I stated that the Hallé Choir’s first ever performance was of Beethoven’s Choral Fantasia in February 1858. However, this performance of The Creation was advertised as celebrating the centenary of the first performance by the choir, said to be of The Creation, in April 1858. The confusion arises because it is very difficult to define what exactly was the Hallé Choir at this time. The February concert was most definitely the first time a choir appeared in one of Hallé’s concert, but the April concert was the first big choral event. In neither instance was the choir called the Hallé Choir, not indeed the orchestra the Hallé Orchestra – that formal naming would not take place until later in the century.

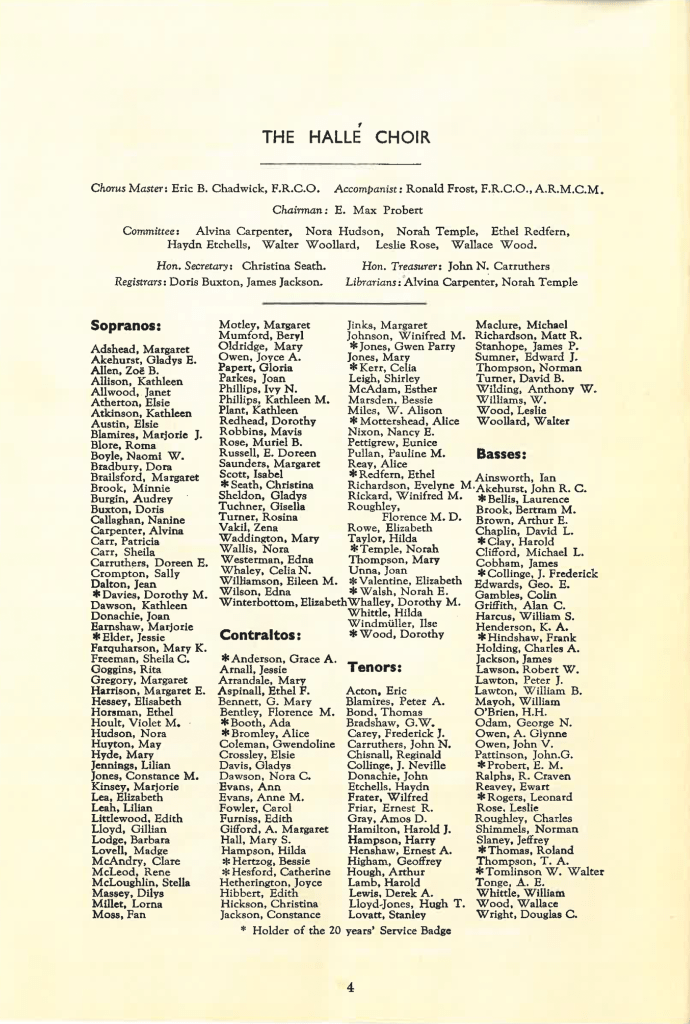

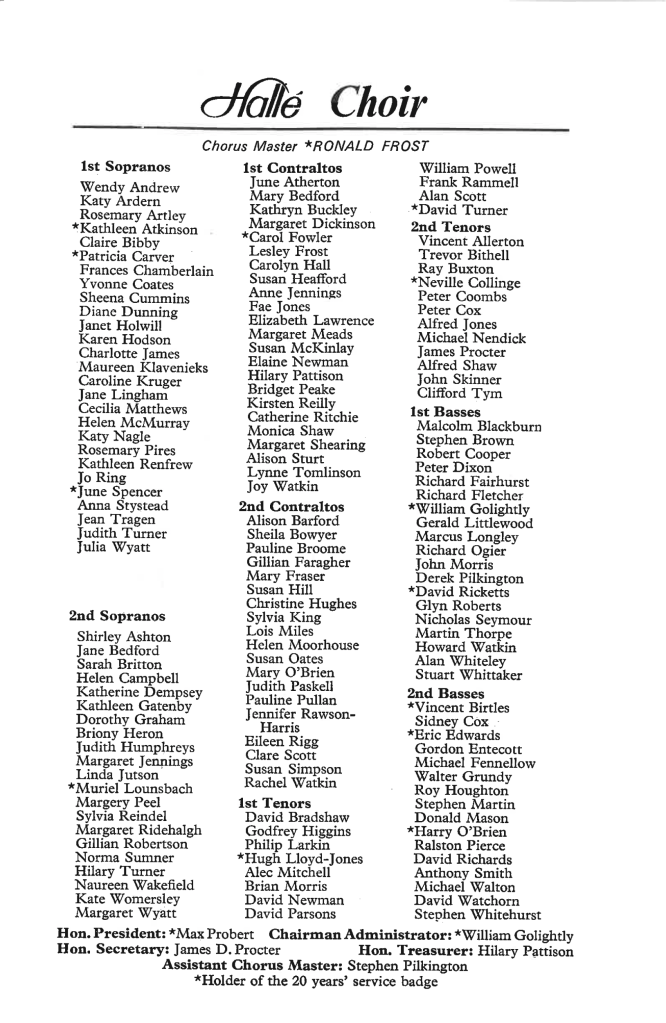

Notwithstanding these semantics, the ‘centenary’ performance was well received, and unlike in the first performance of The Creation in 1858 the choir was named in the programme. I have reproduced the choir list here in case it revives any memories in readers.

Colin Mason was considerably less curmudgeonly in reviewing this concert for the Manchester Guardian than he had been in the previous two reviews I quoted. Noting how rare professional performances of The Creation were at that time, the work having become almost exclusively the domain of amateur choral societies, he nonetheless writes that the performers ‘gave the work as nicely judged a recommendation as it could have, taking pleasure in its innocence without letting it bore them (or us), and avoiding any hint of dramatisation, which quickly makes it appear comic.’ Good job too, one might say – the work is a true Enlightenment work, effervescent in its optimism and as a result always in danger of appearing light and insignificant. For once, Mason also had (mixed) praise for the choir: ‘The Hallé Choir sang well, with animation and a firm if not very bright tone.’ He could not resist one barb though when in finishing he wrote that ‘the weakest part of the performance was the orchestral playing, which had numerous minor blemishes and gave a general impression of a slightly easy-going slackness.’

Groves went on to conduct the choir on three further occasions, conducting Messiah in 1973 and 1980 and Michael Tippett’s A Child of our Time, accompanied incongruously by Handel’s Zadok the Priest, in 1982.

Sir Adrian Boult (first appearance with choir 1962, knighted 1937)

As a Chester resident since the age of four I am quite proud that Adrian Boult, arguably the most eminent British conductor of the 20th century, was born in my home city. He was born in April 1889 in Liverpool Road, Chester, coincidentally the same road where Daniel Craig was born 79 years later! Beginning his professional conducting career in 1914 in of all unlikely places, West Kirby, he soon gravitated to London and after the First World War quickly made a name for himself as a champion of English music, and particularly of Vaughan Williams, many of whose works conducted by Boult in their first performances, including the revised version of the 2nd (‘London’) symphony, and the 3rd (‘Pastoral’), 4th and 6th symphonies. He was appointed as the founder conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in 1930 and later became principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

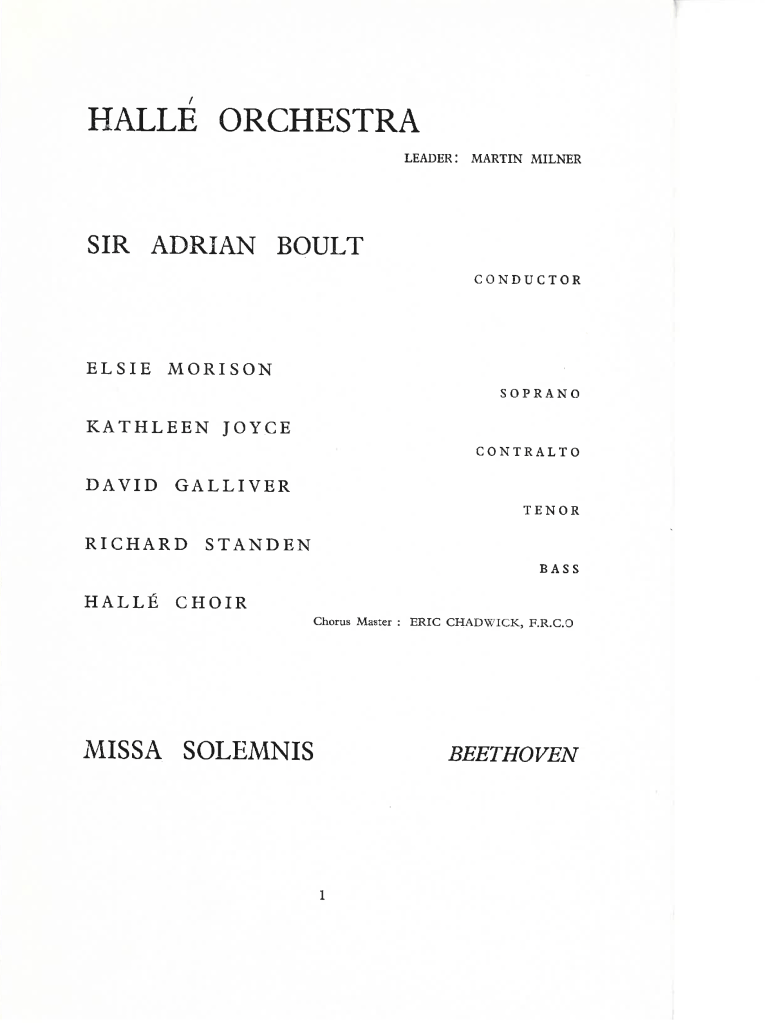

He first conducted the Hallé Orchestra in 1933 in a programme that included Holst’s Perfect Fool ballet suite and Brahms’ 2nd Piano Concerto. Over the next 30 years he conducted the orchestra many times, especially during the 1950s when he would appear nearly every season, often in multiple appearances touring with the orchestra to such unlikely places as Exeter, Plymouth, Barry and Wells. He had an affinity with choirs, as shown by his many recordings of orchestral choral music, and though he conducted Vaughan Williams’ setting for chorus, congregation and orchestra of All People That On Earth Do Dwell a couple of times in southern Cathedrals in the 1950s, he didn’t work with the Hallé Choir until February 1962 when, though still at the height of his powers, he was 73. One might have expected him to conduct the choir in a great English choral work, a Sea Symphony maybe or a Gerontius, but no, the work chosen for him to conduct was Beethoven’s great late choral masterpiece, the Missa Solemnis, a real test of any choir’s mettle.

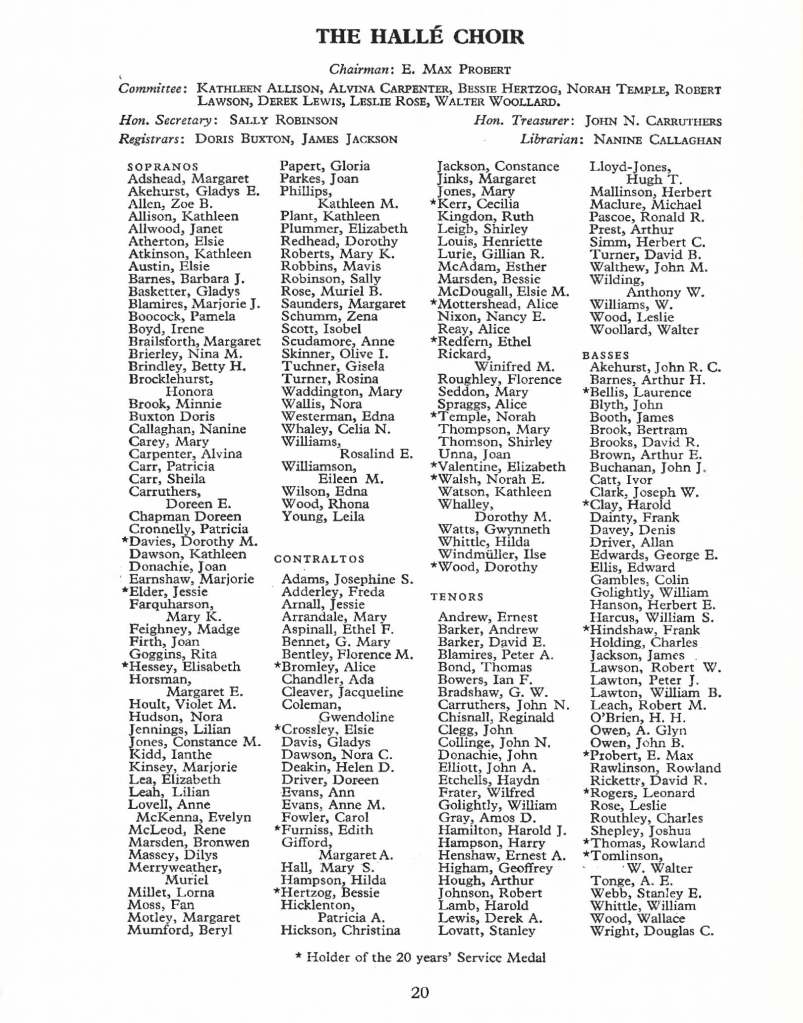

I thought I would reproduce the choir list again for this performance. In my previous blog about women conductors and the Hallé Choir, I noted that John Elliott, one of the singers for the concert that Nadia Boulanger conducted in 1963, is still singing in the choir. This list shows John in his very early 20s appearing with the choir one year earlier, in 1962, 63 years ago! Speaking to John about the concert, he remembered the experience vividly, amongst other things describing Boult’s conducting style as ‘military’.

His near namesake J.H. Elliot, reviewing the concert in The Guardian (as the Manchester Guardian had become in 1959), supports this general perception of Boult as being impressively precise and unhurried:

Sir Adrian Boult conducted the Hallé Choir and Orchestra… in a performance of the Missa Solemnis that had a large measure of the sublime gravity of the music… Sir Adrian, without encouraging spates of rhetoric or seeking for the purple patch, mounded the large lines of this Mass in D with unruffled assurance. Choir, orchestra and soloists responded finely; the spirit was abundantly willing, and the unique grandeur of the work emerged impressively.

From a review by J.H. Elliot in the Guardian, February 19th, 1962

Sir Adrian made only one further appearance with the Hallé Choir, and remarkably it happened in the same year. It was one of the large-scale performances of Messiah that the orchestra used to perform in the King’s Hall at Belle Vue, and one where the choir were joined by the members of the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus, who would have their own performance of the oratorio with Boult and the Hallé the following day in Sheffield City Hall. Perhaps unsurprisingly as an elder statesman of the British conducting scene Boult was not one for what J.H. Elliot in his Guardian review called the ‘back-to-Handel’ movement in a performance the Elliot thought ‘may not be authentic Handel, but is good Handel-Mozart.’ Boult’s last choral engagement with the Hallé came five years later in 1967 with another performance of Messiah in Sheffield with the Sheffield Philharmonic Chorus.

Sir Andrew Davis (first appearance with choir 1982, knighted 1999)

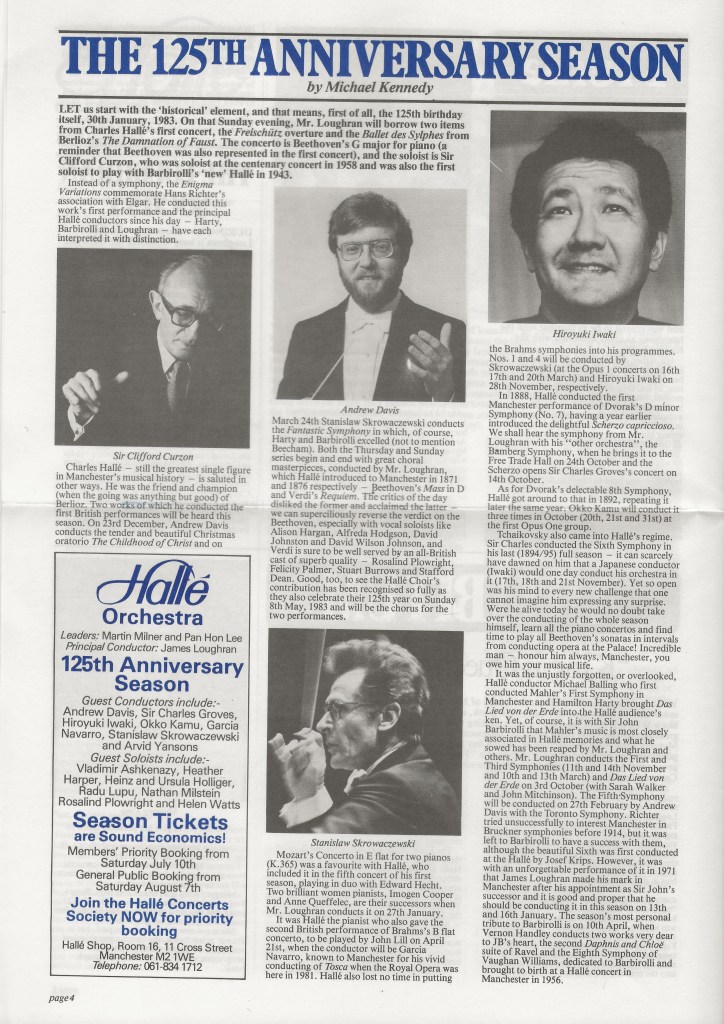

I will finish this survey of the knights that have conducted the Hallé Choir with the last (other than Sir Mark Elder) to have done so, Sir Andrew Davis. In 2022 he conducted the Hallé Choir in a radiant performance with the BBC Philharmonic of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ early choral masterpiece Toward the Unknown Region, as part of the joint Hallé/BBC Philharmonic celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Vaughan Williams. This was a performance I reported in my blog about the relationship between the Hallé Choir and Vaughan Williams. Sir Andrew was 78 at the time of the performance and looked frail, though the performance in the concert of Vaughan Williams’ violent 4th Symphony belied that frailty. Sadly he died last year at the age of 80 leaving behind an immense legacy, especially in the world of opera (he worked at Glyndebourne and was music director of Chicago Lyric Opera for over 20 years) and English music (as principal conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra he championed English music and produced many exceptional recordings of the music of Vaughan Williams including a complete symphonic cycle).

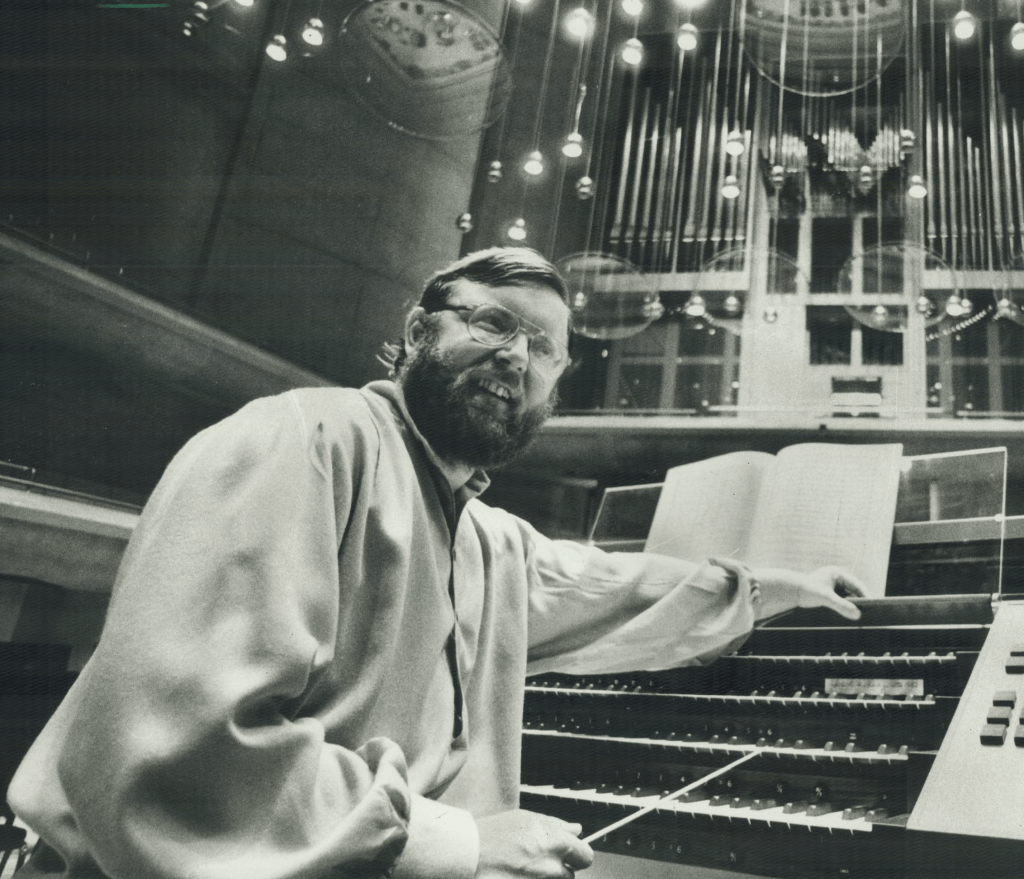

However his first appearance with the Hallé Choir was well before all of this back in 1982 during James Loughran’s time in charge of the Hallé when he conducted the choir and orchestra in a Christmas performance of Hector Berlioz’ oratorio L’Enfance du Christ (‘The Childhood of Christ’) as part of the celebrations of the 125th anniversary of the founding of the Hallé. You can see the publicity material for the anniversary season printed in the July 1982 edition of Hallé News reproduced above. At the time, Davis was the fresh-faced (if already bearded!) principal conductor of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, a role he had taken up when only 31 in 1975. He started his musical career as an organ scholar at King’s College, Cambridge in the 1960s, where of course he would have worked under David Willcocks, and his first professional job was as organist and keyboard player with Neville Marriner’s Academy of St Martin’s in the Fields. It’s interesting that the photo at the top of this section shows him in Toronto not on a podium but at an organ console. Though as I say above he was later best known for English music and opera, these experiences would have engendered a love of the more general sacred repertoire and L’Enfance du Christ was obviously a particular favourite. Indeed, late in life he recorded the work for Chandos with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and a rather stellar quartet of soloist (Sasha Cooke, Andrew Staples, Roderick Williams and Matthew Brook).

What is very much worthy of note is the timing of this concert – 23rd December, 1982. Nowadays, the period from the middle of December through to the first week of the New Year is very much for the Hallé a time for popular Christmas classics, from Hallé Choirs’ own Christmas carol concerts, and performances of The Snowman, through to the annual New Year concert of Strauss waltzes. It is hard to imagine the Hallé of today putting on a concert of L’Enfance du Christ, despite its obvious Christmas connection, two days before Christmas. The nearest we come to it are occasional performances of L’Adieu des Bergers (‘The Shepherd’s Farewell), a chorus from the oratorio anthologised in David Willcocks’ Carols for Choirs! This is probably the reason why, sadly, no reviews seem to exist for the concert, though if any current members of the choir reading this blog have any memories of it (I’ve included the choir list here to help jog those memories) I would love to hear from you.

As far as I can ascertain, Davis made no further appearances with the Hallé Choir until that final Vaughan Williams performance in 2022, so I thought I would include a couple of reviews of that concert that show how even very late in his career, and with minimum apparent effort, he was able to coax powerful performances from the choirs and orchestras he directed, and also demonstrate his lifelong love of the music of Vaughan Williams

First, here’s Robert Beale writing about the performance of Toward the Unknown Region on theartsdesk.com:

It’s early Vaughan Williams, written when he was working on the music of The English Hymnal, and in many ways it breathes the spirit of Anglican services of Evensong (it even has a bit of the chromatic slither that VW himself dismissed as “like the curate improvising” in reference to another composer). But it’s beautifully and harmoniously written for choir and imaginatively scored, and includes that favourite VW melodic motif most widely known as the opening of his tune to “For all the saints” – in this case blazing out, the first note lengthened, to the words “Then we burst forth”. That provides the affirmative, optimistic ending to the piece, which works up to a grand climax near its finish: in effect not quite as rhythmically precise as it might have been at that point, but nonetheless, under direction by Sir Andrew, building on beautiful and transparent textures before it, and making considerable impact helped by the resonant boom of the Bridgewater Hall organ (played by Darius Battiwalla).

From a review by Robert Beale, writing on theartsdesk.com

Secondly, here is Andrew Clements writing in The Guardian:

Joined by the Hallé Choir, he and the orchestra had begun with the carefully shaped account of the work that gives the series [the Hallé/BBC Philharmonic season referred to above] its title, and which here provided a reminder of where Vaughan Williams’ personal musical journey had begun. Walt Whitman’s poetry may not have been the most obvious text for an aspiring British composer in the early 1900s, but the solid, four-square choral setting of it in Toward the Unknown Region is an mistakable legacy of Victorian England; after it would come more Whitman settings in A Sea Symphony, and there the real composer would emerge for the first time.

From a review by Andrew Clements, writing in The Guardian

Thus ends this review of the glorious miscellany of conducting and composing knights that have appeared on stage with the Hallé Choir. The choir have a concert with Sir Mark Elder lined up for the 2025/26 season (a performance of Rachmaninov’s Spring cantata) and hopefully many more in the future, but given that footballers, cricketers and rock stars now seem to be more frequently knighted than classical conductors the chances of further concerts with knights of the realm seem less than they used to. Whilst a concert with Sir John Eliot Gardiner may now seem beyond the pale, maybe the Hallé Concerts Society can persuade Sir James MacMillan, Sir Antonio Pappano or ever Sir Simon Rattle to come to Manchester in the near future to make their debuts with the Hallé Choir!

References:

Andrew Burn. ‘Bliss, Sir Arthur Edward Drummond (1891–1975), composer’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Anthony Boden, Three Choirs – A History of the Festival: Gloucester, Hereford, Worcester, (Stroud: Sutton, 1992)

Andrew Burn. ‘‘Now, Trumpeter for Thy Close’: The Symphony ‘Morning Heroes’: Bliss’s Requiem for His Brother.’ The Musical Times, vol. 126, no. 1713, 1985, pp. 666–68.

Charles Groves. ‘The Creation’ Hallé – Magazine for the Music Lover, Number 108, November 1958, pp. 13/14.

Simon Heffer. ‘Willcocks, Sir David Valentine (1919–2015), conductor, organist, and composer’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 10, 2019. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Michael Kennedy. ‘The 125th Anniversary Season’ Hallé News, July 1982, p. 4.

Brian McFarlane. ‘Attenborough, Richard Samuel, Baron Attenborough (1923–2014), actor, film director, and film producer’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018)

Robert Ponsonby. ‘Groves, Sir Charles Barnard (1915–1992), conductor’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004)

John Rutter, Remembering David Willcocks (1919-2015), (December 19th, 2019) https://johnrutter.com/latest-blog/remembering-david-willcocks-1919-2015

Anon. ‘Photograph of Richard Attenborough’ Hallé – Magazine for the Music Lover, Number 91, December 1956, p. 12.

theartsdesk.com and theguardian.com for online concert reviews

Hallé Archives (with thanks to Heather Roberts for scanning the programmes and cuttings)

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Leave a comment