Introduction

The history of the Hallé Orchestra is defined by the many great chief conductors that have graced the podium of the Free Trade Hall and the Bridgewater Hall, from Charles Hallé himself through to Mark Elder. It is in the nature of the British honours system that many of these conductors were eventually knighted – Hallé and Elder obviously, but also Sir Hamilton Harty, Sir John Barbirolli and two conductors engaged by the society in the long interregnum between those two conductors’ tenures, Sir Thomas Beecham and Sir Malcolm Sargent.

What I thought I would do in this blog was to look at some of the other musical knights that have been involved with the Hallé, and specifically with the Hallé Choir, along the way. Some conducted the choir early in their careers, before their fame led the establishment to honour them. Most are still counted among the great and the good of the last 150 years of British musical excellence, either just as conductors or as composer/conductors who conducted the choir in performances of their own works. In what will be the first part of a two-part blog I will look at a composer who after his first appearance with the choir achieved fame in a way he could not have expected, fame with which he could never quite square his musical integrity, Arthur Sullivan.

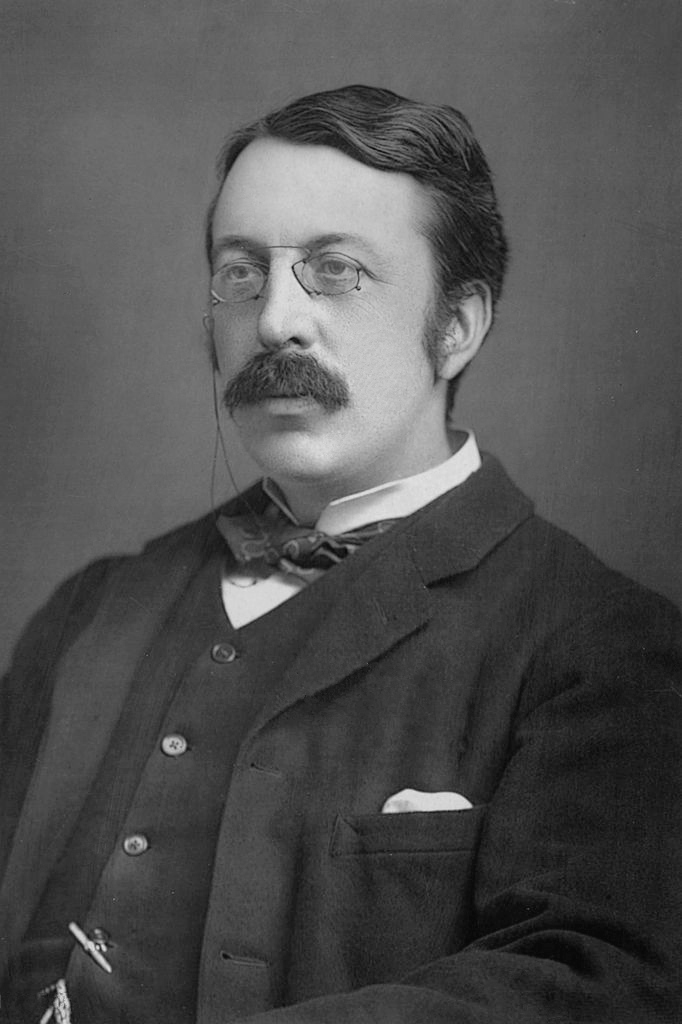

Sir Arthur Sullivan (first appearance with choir 1870, knighted 1883)

Arthur Sullivan is of course best known today as one half, along with W.S. Gilbert, of Gilbert and Sullivan, the renowned writers of late Victorian comic operas that became known as the Savoy Operas after the theatre the impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte built to stage them – the Savoy Theatre. Gilbert would write the witty and acerbic lyrics to the operas, often satirising the stuffy conventions of Victorian England, and Sullivan would write the instantly singable tunes.

However, Sullivan always had pretensions to being a much more serious composer than that, and constantly felt held back by the musical restrictions imposed on him by the limitations of the comic opera genre. His musical education had been serious in the extreme, with spells at the Royal Academy of Music and the Leipzig conservatoire, where he studied under Carl Reinecke, the conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra who had himself studied under Mendelssohn, Schumann and Liszt.

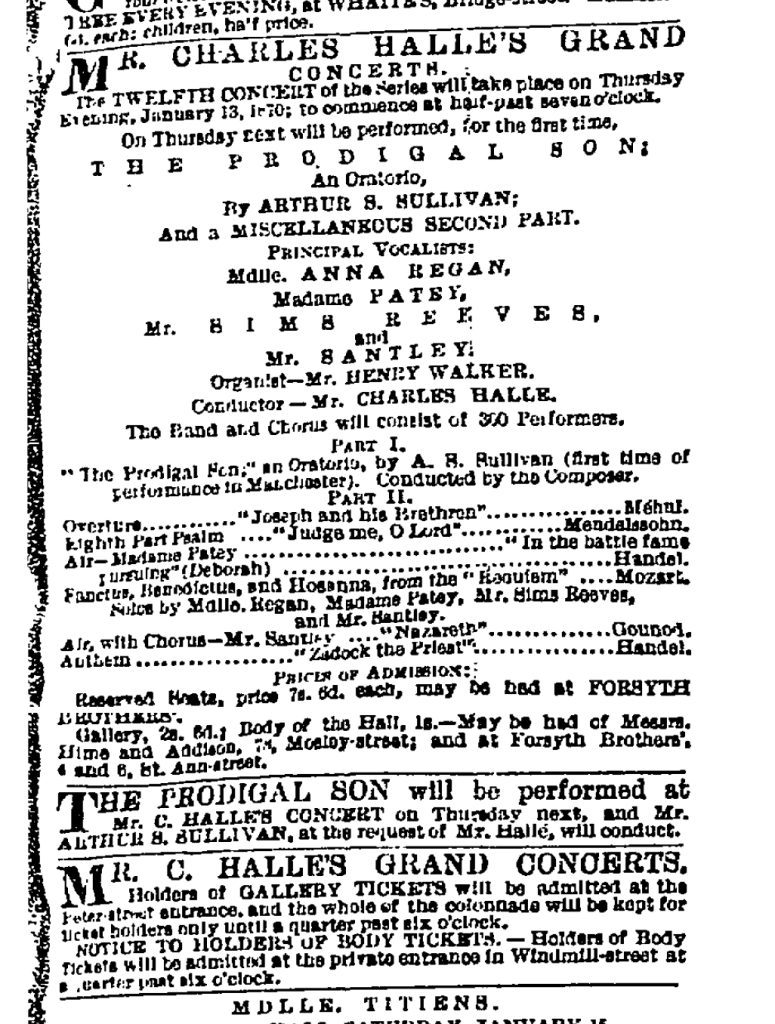

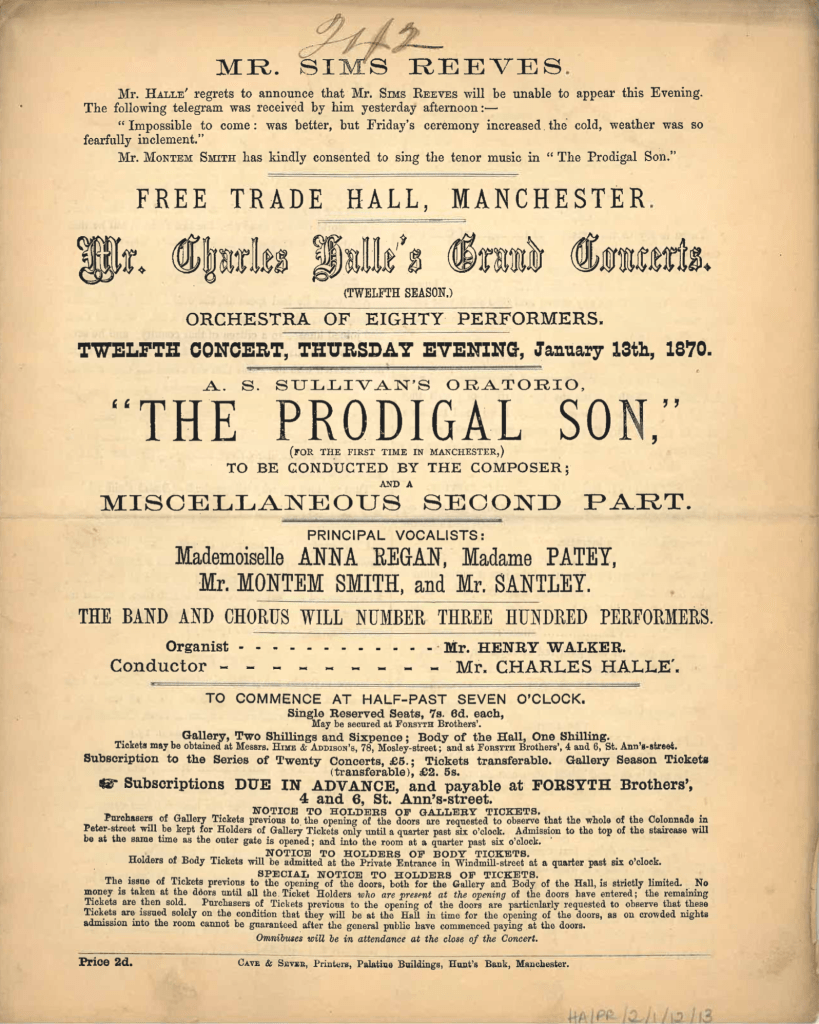

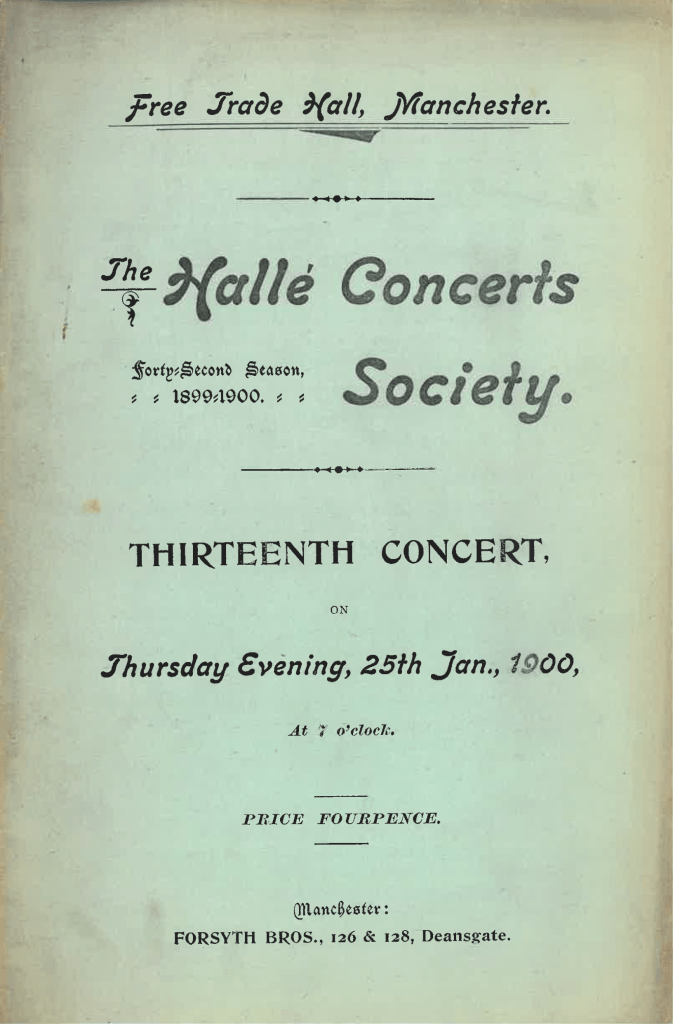

At the beginning of 1870, at the age of just 27, he was engaged by Charles Hallé to conduct one of his early works, the oratorio The Prodigal Son, in what would be its first performance in Manchester. This was a rare honour, as Hallé conducted the vast majority of Hallé concerts at this time, and indeed conducted the rest of the programme on this particular night.

Sullivan had already packed a lot into a then brief composing career, including a short comic opera Cox and Box, which was a great success and was the work that brought him to the attention of W.S. Gilbert. He had also recently composed the exquisite part-song The Long Day Closes, still one of the finest examples of that genre, and in 1870 would go on to compose his first major work for orchestra alone, Overture di Ballo, and the music to Sabine Baring-Gould’s hymn, Onward Christian Soldiers. His first collaboration with Gilbert, the one-act opera Trial by Jury, the work that would both seal his fame and bind him musically, was still five years in the future.

The Prodigal Son, set to a libretto taken from St Luke’s Gospel and elsewhere in the Bible, was written for the Three Choirs Festival in Worcester Cathedral in September 1869, so the first Hallé performance on January 13th, 1870 was less than four months after the premiere. It was very much a serious piece on a serious subject, one rarely addressed musically. Indeed, the only piece of music on the subject that is still regularly performed is the ballet score of the same name that Sergei Prokofiev wrote for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1929 and which was recently revived by the Royal Ballet. Sullivan’s oratorio proved to be a popular addition to the choral repertoire, as was Sullivan’s later oratorio The Golden Legend, and over the following years received many performances in Britain and North America, becoming a staple of the choral society repertoire until its fame gradually declined in the first half of the 20th Century.

Indeed its perceived importance was already so great in January 1870 that the Manchester Guardian felt impelled to print an extensive preview of the piece on the morning of the concert. This included both a section-by-section breakdown of the structure of the piece, with inevitable references to Mendelssohn whose oratorio Elijah had kick-started a renewed interest in the oratorio form, and also a long quote from Sullivan himself about the genesis of the piece which included the following:

It is a remarkable fact that the parable of the prodigal son should never before have been chosen as the text of a sacred musical composition. The story is natural and pathetic, and forms so complete a whole; its lesson is so thoroughly Christian; the characters, though few, are so perfectly contrasted; and the opportunity for the employment of ‘local colour’ is so obvious that is indeed astonishing to find the subject so long overlooked

Arthur Sullivan quoted in ‘The Prodigal Son’, the Manchester Guardian, January 13th 1870

The run up to the performance itself was not without controversy. The Worcester premiere included the renowned tenor Sims Reeves. Reeves was engaged for the Manchester performance, but was beginning to gain a reputation for cancelling appearances, and as can be seen from the notice at the very top of the programme for the Hallé concert, this is exactly what happened here with Reeves’ part being taken at short notice by Montem Smith. This was becoming an ever more regular occurrence at Hallé concerts (Michael Kennedy suggests that the underlying cause was gout, presumably caused by excessive drinking), and though prior to 1870 Reeves made 48 appearances with the orchestra, after 1870 he made only one further appearance, 1872.

What of the performance itself? The Guardian reviewer, who initially commented on the fact that, because it was new music, there was ‘lacking that instinctive cohesion which characterises the performances of well-known works’, leading to ‘very perceptible’ deficiencies, nonetheless considered the performance could be ‘pronounced a successful one’. He praised the choir in a couple of the choruses in particular, and his final verdict is a strong one, with the work as he describes it seeming a world away from the fripperies of the Savoy Operas:

It is doubtful whether a finer choral work has been produced in England since the death of Mendelssohn; and the promise it affords of the future is such as to justify the highest expectations from its gifted composer

From an anonymous review in the Manchester Guardian, January 14th 1870

On the other side of his Savoy Opera fame, Sullivan was to conduct the choir on one further occasion in 1889, in a performance of his later oratorio The Golden Legend, an event I covered in my blog about the career of the Hallé Choir’s longest serving choirmaster, R.H. Wilson.

Though The Golden Legend was performed nine times between 1887 and 1915, The Prodigal Son, for all the claims to its greatness made by the Guardian reviewer, was never performed again by the choir. The most recent performances of Sullivan’s music by the Hallé Choir, both in the early 2000s, were of two of the best known of the Savoy Operas that Sullivan wrote with Gilbert, The Mikado and Iolanthe. While both are undeniably brilliant examples of their genre and deservedly successful, by all accounts they were not pieces that Sullivan would have wanted to be his musical legacy. Such is the burden of popular fame.

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (first appearance with choir 1885, knighted 1902)

Whilst Arthur Sullivan provided a suggestion of a renaissance in British music, my next musical knight, the career of Irish-born Charles Villiers Stanford provided tangible evidence of it. Born in Dublin in 1852 to musical parents (his father had sung the bass solos in the Irish premiere of Elijah), Stanford’s early career had distinct parallels with Sullivan. Like Sullivan he had composition lessons with Carl Reinecke and like Sullivan one of his early compositions was a setting of Longfellow’s poem The Golden Legend.

Whilst he achieved considerable success in his lifetime as a composer, nowadays he is largely known for his church settings and his two song cycles for baritone, male chorus and orchestra, Songs of the Sea and Songs of the Fleet, and his importance in retrospect is largely pedagogical. As a professor of composition from the 1880s onwards at the newly opened Royal College of Music he was pre-eminent. Though his own music harked back to German models, many of his pupils were engaged in the flowering of a new, distinctively English style of music that harked back to earlier English classical and folk traditions and forward to the new century. His list of pupils reads like a Who’s Who of early 20th century British compositional talent – Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst, George Butterworth, Ivor Gurney, John Ireland, Rebecca Clarke, Frank Bridge and Arthur Bliss to name just a few.

Many of these, such as Vaughan Williams, were consciously trying to break free from the restrictions imposed by Stanford and his colleague Hubert Parry, who also taught Vaughan Williams for a while, even as in their early composition lessons they wrote music that conformed with their teachers’ preferences. As Vaughan Williams wrote in a letter to John Ireland in 1952 about one of his early works, Heroic Elegy: ‘Mine was a horrible amateurish business now happily lost – it so happened that its style fitted in for the moment with C.V.S’s [Stanford’s] prejudices’.

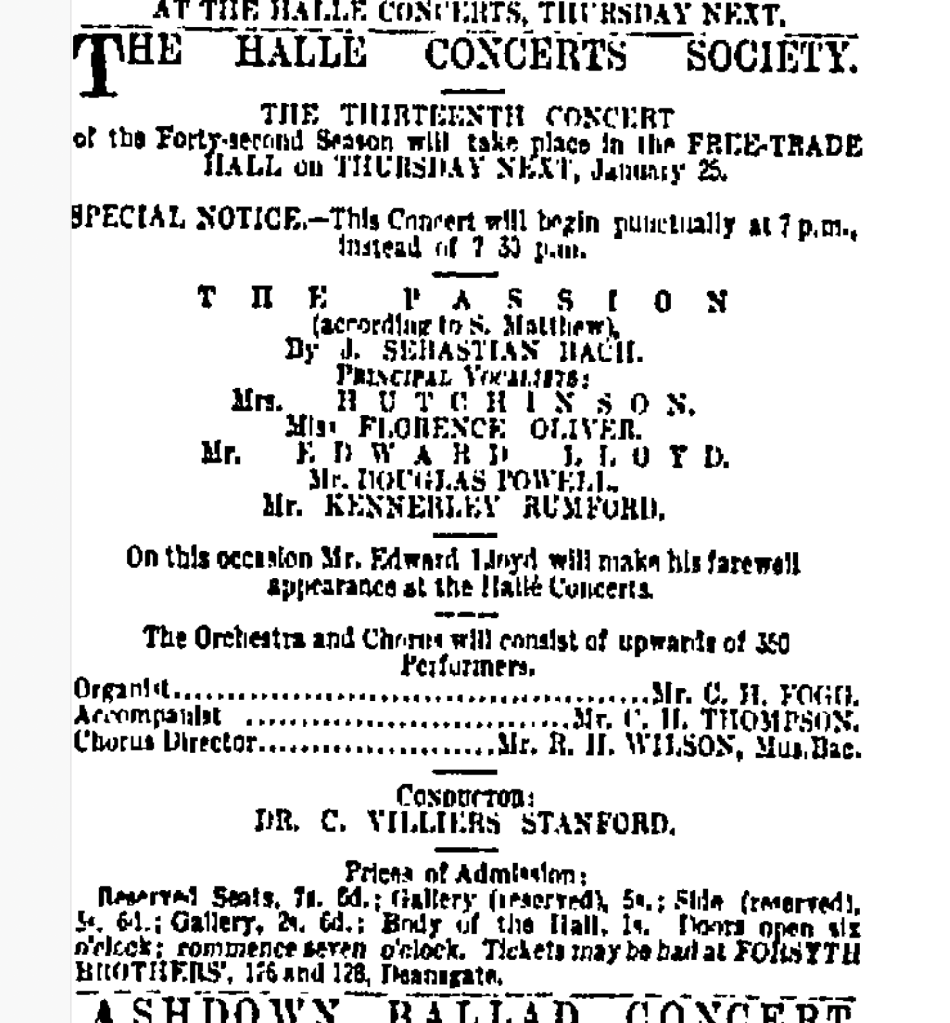

Stanford was therefore an important figure, not least in the world of choral music, both through his compositions and his work as a choral conductor – for example he was conductor of the Bach Choir from 1885 to 1902. It is no surprise, therefore, the he was invited to conduct the Hallé Choir on three occasions, beginning in 1886 with a performance of his 1885 oratorio The Three Holy Children, a work now very much neglected even though, remarkably, it finally received its American premiere only last year in Minneapolis. Ten years later he conducted the choir in the Bach St Matthew Passion, a work that he reprised four years later in January 1900. Within this blog I will generally write in detail about the first concert our featured knight conducted with the choir but in this instance I would like to go into detail on this 1900 concert, partly because of the circumstances in which it took place and partly because it harks back to an earlier blog.

Charles Hallé’s death in 1895 had been followed by a largely unhappy period in which yet another conducting knight, Sir Frederic Cowen, took over the directorship of the Hallé. Cowen’s short reign ended in 1899 and Hans Richter was appointed as his successor and hopes were high for the future of the orchestra. Richter did indeed make an impression during his 12 years in charge, though this period was without controversy. Indeed, no sooner had he taken up the reins as chief conductor at the beginning of the 1899-1900 season than he was called away for an engagement conducting opera in Vienna. Various conductors had to step into the breach, including the young Thomas Beecham, who largely through the influence of his father conducted a concert in St Helens two days after Richter departed for Vienna, and Stanford, who undertook to conduct a number of concerts in Manchester around the turn of year. This task merited editorial comment in the Manchester Guardian as the run of concerts finished:

The musical interregnum cased by Dr Richter’s unavoidable absence from Manchester during December and January came to an end with the last Hallé Concert… …thanks are due to Dr Stanford, the deputy conductor, who stepped into the breach and performed a rather thankless task during Dr Richter’s absence… No man could undertake such a job without subjecting himself to unfavourable comparisons; but Dr Stanford undertook it and thus helped the Committee out of a difficulty, and his five concerts were, on the whole, quite as successful as could have been expected.

From an editorial in the Manchester Guardian, January 29th 1900

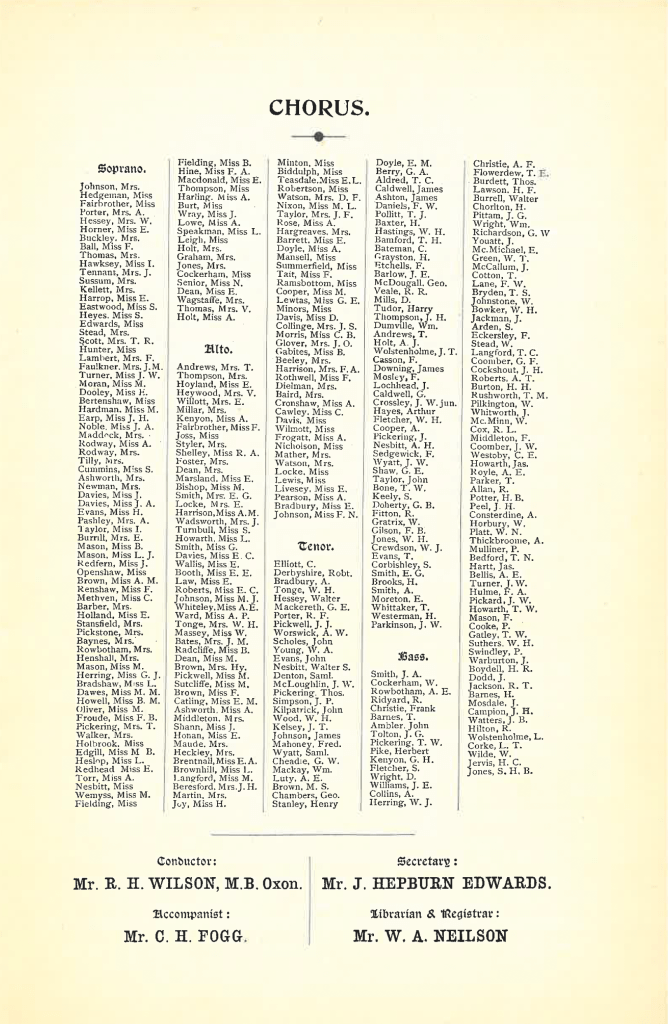

Referring back to the St Matthew Passion performance that had taken place the previous Thursday, the same editorial goes on to suggest that some of the weight was taken off of Stanford’s shoulders by the special nature of the performance, in which ‘public attention was concentrated on Mr Lloyd’. The editorial went to state that with the ‘warmth of the farewell demonstrations made in honour of that justly popular singer’, ‘the conductor was forgotten’. The ‘Mr Lloyd’ in question was the renowned tenor Edward Lloyd, who had announced that, at the age of nearly 55, this would be his farewell Manchester performance following on from a performance of Messiah the previous month. Lloyd had appeared in the first performances of many Victorian oratorios, including Sullivan’s The Golden Legend, and had performed many times with the Hallé in Manchester dating back to 1873. Ironically, one of Lloyd’s early starring performances had been at the triennial Handel Festival at the Crystal Palace in 1877 when he deputised for the (surprisingly!) indisposed Sims Reeves. Though, as I say, this was to be his last Manchester performance, he continued performing for the remainder of 1900, having what some might call the misfortune to be the soloist at the first performance of The Dream of Gerontius, which by all accounts was not his finest hour.

The Manchester Guardian reviewer was sympathetic to Lloyd with regard to his farewell performance, describing him ‘singing… with matchless art which gave particular point to the great demonstration of farewell good wishes accorded to him at the end of the oratorio’. The reviewer did, however, have a number of gripes, aimed at the organ (‘how much longer… is musical Manchester going to allow that antediluvian makeshift of an organ in the Free-trade Hall to spoil every choral concert?’), the translation of the words (‘the bewildered audience often found themselves listening to words entirely different from those printed in the programme’), and the audience (‘the standing nuisance and disturbance caused… by members of the audience who leave their places… wandering round the hall… without the faintest consideration either for those who have to perform or those who wish to listen’). After this vitriol the choir themselves only get a brief mention at the very end of the long review:

The choir were at their very best in the wonderful restful double chorus that opens the work and in the unaccompanied chorale – last of the five versions with different harmony, but all based on the Lutheran hymn “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden”, that occur in the work.

From an anonymous review in the Manchester Guardian, January 26th 1900

Remarkably, and probably the reason why the writer of the editorial a few days later felt he had to be mentioned, there is no reference to Stanford by name within the review, other than to describe ‘the conductor’ as ‘one of the greatest authorities of Bach now living in this country, and a great Bach enthusiast’. This was not a happy reviewer, who while avowing that whilst the performance was ‘not bad or incompetent’ wrote that ‘it left a fragmentary, disturbed and unconvincing impression.’

Before leaving this concert, I need to explain the link to a previous blog that I referred to earlier. This was the blog in which I recounted the choir’s early history with the music of Elgar and related it to the personal history of an ordinary member of the choir who had sung in the first Hallé performance of The Kingdom, the alto Edith Nicholson. That performance was in 1907, but if you look at the list of choir members for the 1900 concert shown above you will see that ‘Miss Nicholson’. At that time she would have been only 22 and very much one of the younger members of the choir, living in Alan Road, Withington with her widower father and their one servant. As I said in the previous blog, it is wonderful to find these human connections within the choir’s history, and I hope in a future blog to take a number of choir names at random and trace their individual histories and gain a deeper picture of the rich and varied makeup of the choir.

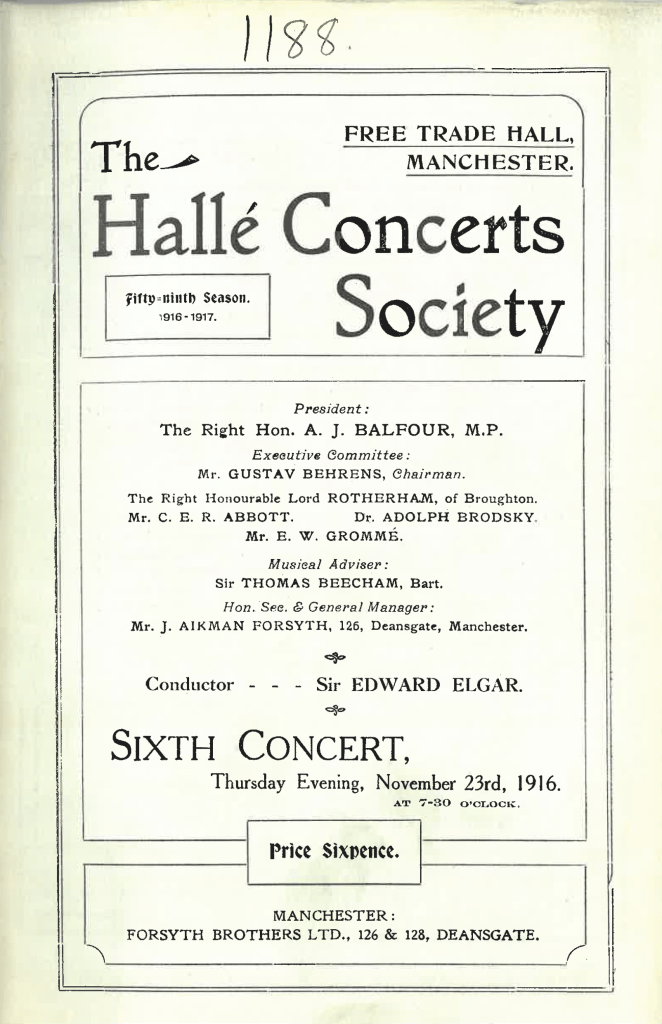

Sir Edward Elgar (first appearance with choir 1916, knighted 1904)

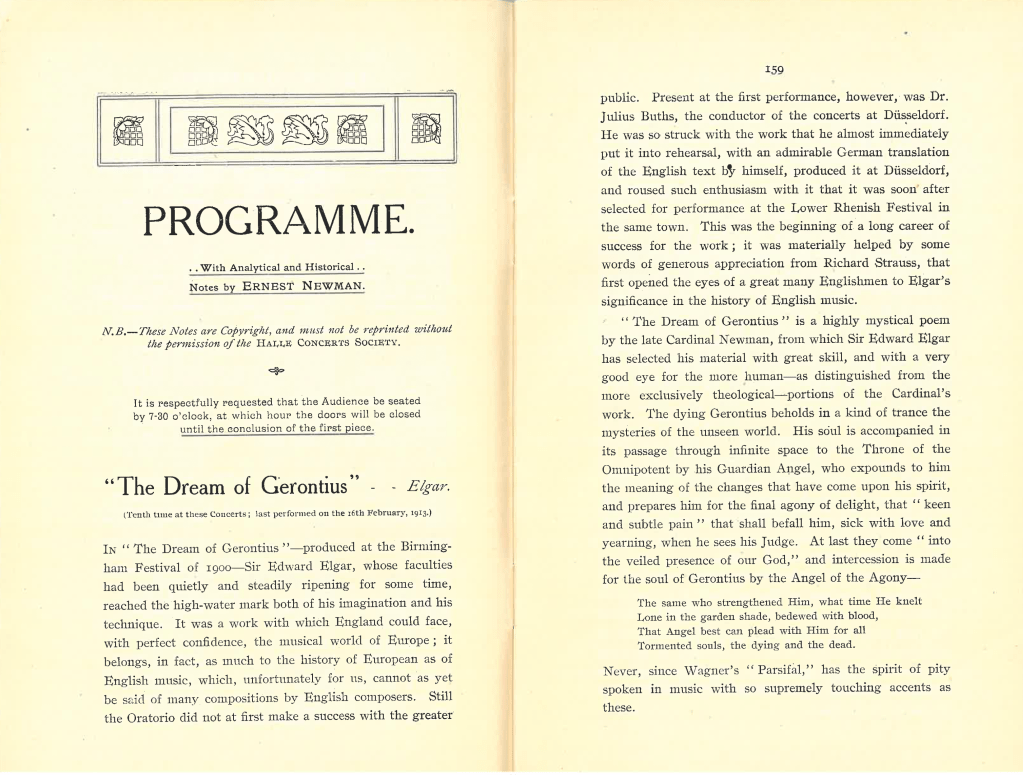

Mention of Edith Nicholson and the performance of The Kingdom in 1907 brings us to perhaps the most illustrious musical knight to have conducted the Hallé Choir, Sir Edward Elgar, who, whilst not being as forward looking as the young innovators taught by Stanford, was an integral part of the revival of interest in English music at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries.

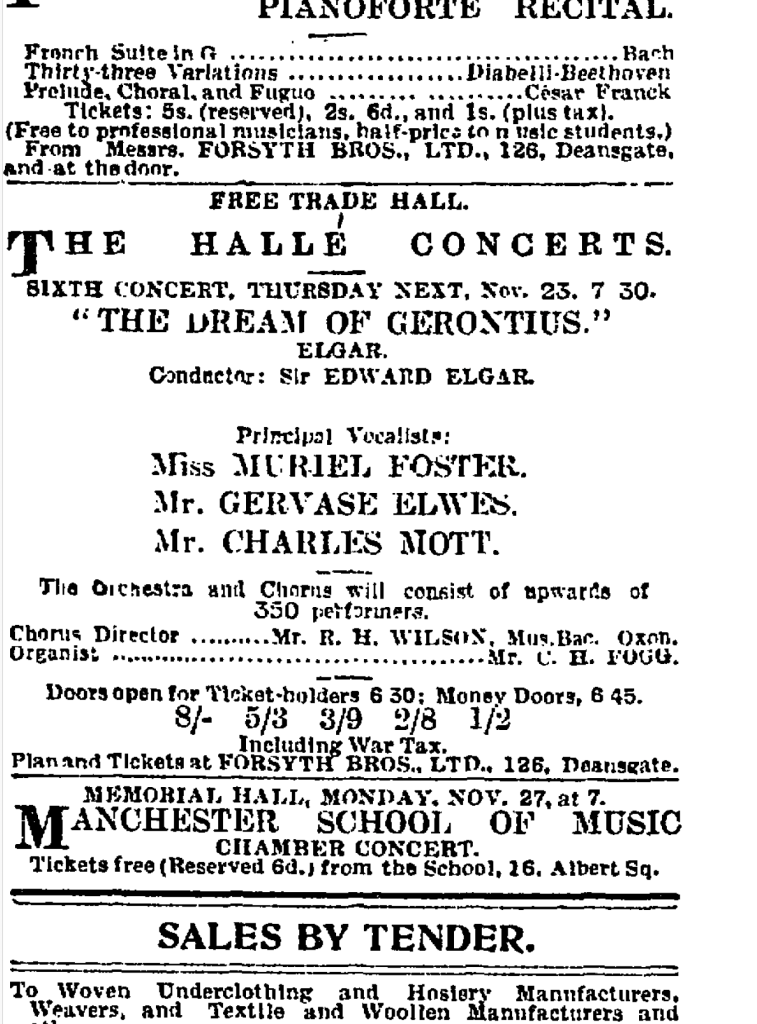

I won’t repeat what I wrote about Elgar in the Edith Nicholson, suffice to say that he conducted the Hallé Choir on two occasions, both times in performances of his best-loved oratorio, The Dream of Gerontius. Elgar’s first appearance in front of the orchestra was actually in 1900 in a programme which included a performance of his orchestral song cycle Sea Pictures with the redoubtable Dame Clara Butt. In 1915 he conducted a programme which included Berlioz’ Te Deum, his part song Love’s Tempest and the final chorus from his early oratorio Caractacus but that concert was in Bradford’s St George’s Hall and the choir was the Bradford Festival Choral Society.

In retrospect it is slightly surprising that big concerts such as the Bradford concert and the Hallé performance a year later of Gerontius took place at all. They were taking place, after all, at the very epicentre of the First World War, and looking at the Hallé Choir’s performances during the Second World War they were few and far between, mostly limited to single performances of Messiah at Christmas. However, at the very outbreak of the First World War, Gustav Behrens of the Hallé Concerts Society made a pledge that concerts would continue, including choral concerts, no matter what ravages war might make on the composition of the orchestra and choir: ‘Recreation is a necessity and becomes even more desirable when each day brings with it sorrow and anxiety’. I have looked at the minutes of the orchestra’s Pension Fund during this period and they are full of mentions of orchestra members serving on the front (as are the concert programmes of the period), and of those who sadly had lost their lives, and I am sure the choir were hit in similar ways.

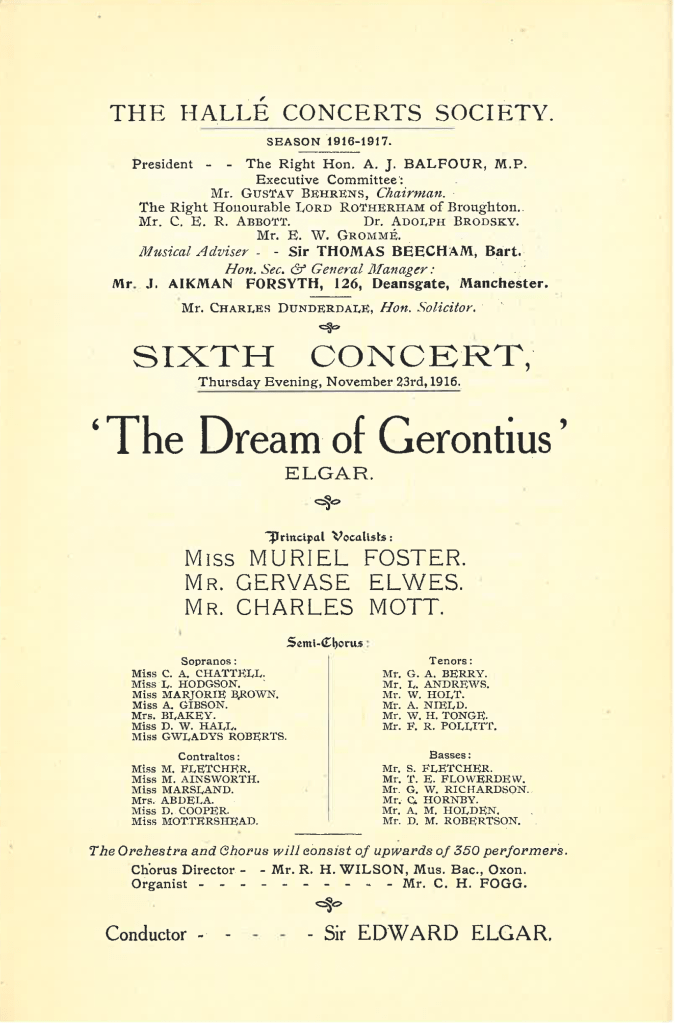

Nonetheless, both choir and orchestra assembled at the Free Trade Hall on November 23rd 1916, just a few days after the end of the Battle of the Somme, to sing the oratorio that the Hallé Choir had made their own under Hans Richter. This time it was to be the composer himself conducting the choir and the list of soloist matched the occasion, with the part of Gerontius sung by the renowned tenor Gervase Elwes who had become very much associated with the role over the years since his first performance of the oratorio in 1904. The role of the Angel was taken by Muriel Foster, who had sung in the first performances of The Kingdom, The Apostles and The Music Makers, and so was indelibly linked with the music of Elgar. The choir were, of course, trained by the veteran choirmaster R.H. Wilson, and as can be seen from the concert advertisement, despite the privations of war the orchestra and chorus were expected to number more than 350 performers.

The success of the concert was addressed in the very first paragraph of Samuel Langford’s review in the Manchester Guardian:

Not for many years has Sir Edward Elgar had such an enthusiastic reception in Manchester as at the performance of “The Dream of Gerontius” which he conducted in the Free Trade Hall last night, and not for some years has the Hallé Chorus sung through a work with so much brilliance and just variety of colour.

From a review by Samuel Langford in the Manchester Guardian, November 24th, 1916

As it continued, the review was light years away from the griping that accompanied the 1900 Bach review that I quoted above. Writing about Elgar’s conducting, Langford described ‘the absolute justice of every change of tempo and style’, writing that ‘this was a tremendous factor in establishing the cohesion of the work.’ Muriel Foster ‘fulfilled every expectation of those who heard her in the work when it was new’, and Gervase Elwes ‘rarefied the expression in the second part of the work most wonderfully, and with an unusual sense of vocal ease’.

As for the choir, according to Langford the famous Demon’s Chorus, the section of the work every choral society member since 1900 has dreaded the most, was handled with ease:

The Demon’s Chorus, once a hazard, was now handled with a kind of daring which made all flaws negligible in their effect. Whether to praise chorus or instrument most one would not know, for each so greatly inspired the other.

Samuel Langford

Finally (and most importantly for any choir!) ‘both the chorus and semi-chorus were well supplied with rich soprano voices’.

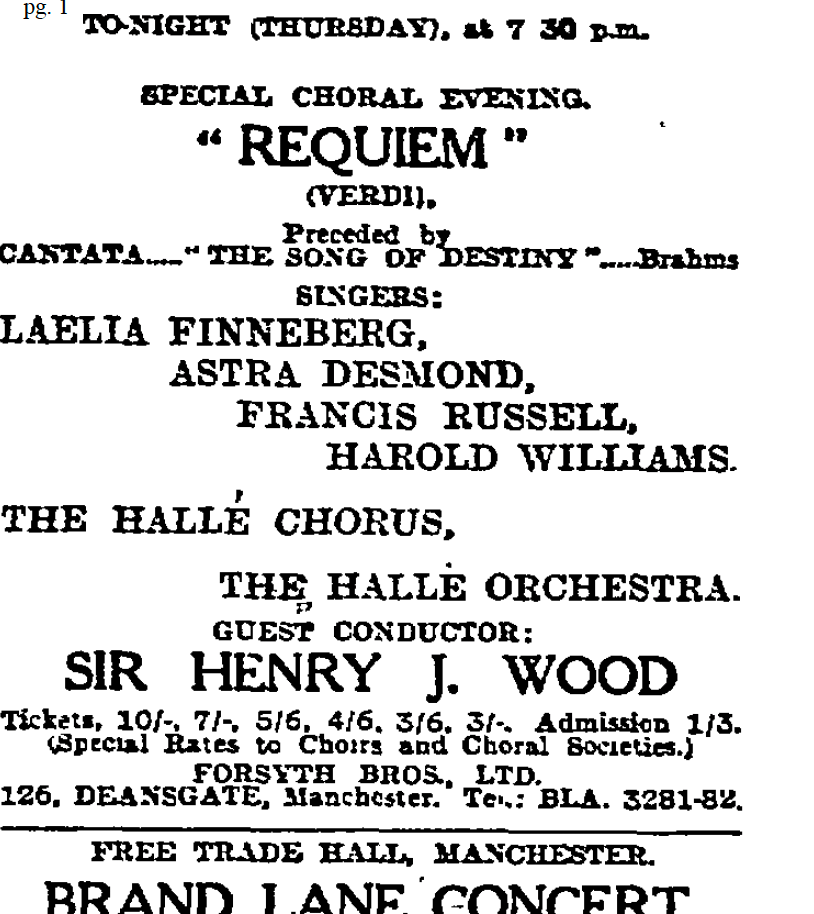

Sir Henry Wood (first appearance with choir 1933, knighted 1911)

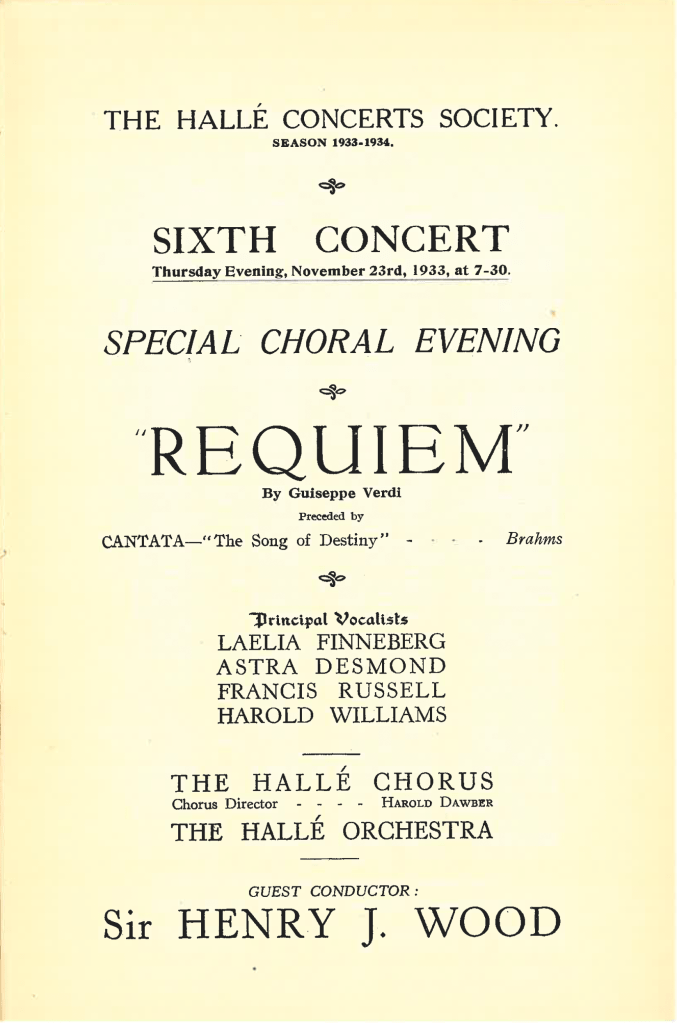

For our final musical knight in this first part of the blog, we jump forward to 1933 and the first occasion that the Hallé Choir was conducted by the father of The Proms, Sir Henry Wood. I described in a previous blog how Wood and Robert Newman established the series of regular summer concerts in London that survive today in the form of the BBC Proms, and at which the Hallé Choir have made regular appearances (including one scheduled for this August). The choir’s first Proms appearance in London was many years away when the 64 year old Wood was invited to conduct the choir for the first time in a ‘special choral evening’ performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s mighty Requiem, along with Brahms delicate Schicksalslied (‘Song of Destiny’) as an appetiser.

The concert took place on November 23rd 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, which affected musicians much as it affected any other working man or woman. The day after the concert, the Manchester Guardian included a piece in its In Manchester column about ‘The Unemployed Orchestra’, an orchestra founded In Manchester to provide help and assistance to struggling musicians, and its associated body, ‘The Unemployed Male Voice Choir’, founded to assist singers on a similar basis.

Like John Barbirolli, Henry Wood had humble origins, his father a shopkeeper in Hitchin, Hertfordshire, and according to Jessica Duchen, he always ‘retained a hint of “the lower middle class” in his accent’. As such he must have had an affinity with the cause of the unemployed, and you will see from the Guardian column below that he was to return to the Free Trade Hall the following month to conduct the Unemployed Orchestra in a concert for the Lord Mayor’s Fund.

As for the Hallé Choir concert, Neville Cardus wrote a long, witty and typically erudite review in that same edition of the Manchester Guardian. For example, here is his description of the task Wood had at hand given the nature of the work being performed:

The external aspects of Verdi’s emotionalism in the Mass are, as I say, likely to strike English folk as so much theatre stuff. All in all, then, Sir Henry Wood’s task was hard; leadership at the Hallé Concert under the circumstances was about as cheering as that of Uriah the Hittite. To his eternal credit, Sir Henry gave us a magnificent performance of this masterpiece.

From a review by Neville Cardus in the Manchester Guardian, November 24th, 1933

It appears from the review that Wood must have worked with the choir a number of times in preparation for the concert, which if true would be unusual – most of the work would have been expected to have been done by the choral director Harold Dawber. Whoever was responsible, however, Cardus was impressed: ‘Seldom has the Hallé Chorus sung with more life and point than last night. The volume of tone was capital, with apparently that power of reserve which counts the most in the end.’ Yes, there were ‘defects’, largely caused, Cardus suggests, by the normal practice at the time by which the first time the choir sang with the orchestra would be the concert itself, a practice unthinkable today. He did cavil slightly at the choir’s performance of the ‘Quantus tremor’ passage, but leavened his criticism with humour:

Here we need not only vocal but histrionic art. It is too much to expect of English choralists a sudden and complete forgetfulness of the comfortable faith of countless oratorios, all resting in the Lord. Even the opening agony of Elgar’s “Gerontius” has often gone beyond the average English vocalist’s notion of the macabre.

Neville Cardus

Cardus saves his biggest revelation for the last paragraph, when he writes that ‘for all this moving and nobly presented music the Free Trade Hall was nearly half-empty’. He presents the November fog as a possible reason, though adds the barb that ‘more likely it was because no fashionable pianist was there to alleviate an evening entirely devoted to music’.

As a footnote to this concert, one of the problems all conductors have to face is that of advertised soloists pulling out at the last minute. It happens now, and it happened then, as we saw above when Sims Reeves absented himself from the Sullivan concert. It happened here too. Given she was named in an advertisement on the morning of the concert, Astra Desmond must have dropped out at the very last moment. Muriel Brunskill would, however, have been a more than adequate replacement

Wood went on to conduct the Hallé Choir on two further occasions, a performance of Vaughan Williams’ A Sea Symphony along with the Handel Coronation Anthem The King Shall Rejoice (an unlikely pairing) in 1936 and a performance of Bach’s monumental Mass in B Minor in 1938. The next part of this blog look at musical knights who have worked with the Hallé Choir since the Second World War.

References:

Jessica Duchen, “Henry Wood – The First Knight of the Proms”, The Independent (April 23rd 2007).

Christopher Fifield. Hans Richter, (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2016)

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition – A Century of Music, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

Letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams to John Ireland (Letter No. VWL2479), from The Letters of Vaughan Williams (London: Vaughan Williams Foundation) https://vaughanwilliamsfoundation.org/letter/letter-from-ralph-vaughan-williams-to-john-ireland-2/

Three Holy Children (The Stanford Society, 2024) https://www.thestanfordsociety.org/events/three-holy-children

Hallé Archives

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Leave a comment