Introduction

In my previous blog describing the Hallé Choir’s history of radio broadcasts I noted that February 5th, 2025 marked the 100th anniversary of the choir’s first appearance on radio, a performance of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius relayed live from the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Within this blog I will look at the choir’s many appearances on television, the first of which (as far as I can ascertain) took place just over 50 years ago in 1974.

On 26th January, 1926, the year after that first Hallé Choir radio transmission, the world’s first public demonstration of a working television system, in which both sound and pictures were transmitted, was given by Scottish engineer John Logie Baird – his so-called ‘Televisor’ system. Though his initial system only had 30 lines, by the 1930s he was doing transmissions of plays in the new medium and in 1931 transmitted an outside broadcast of The Derby.

By 1935 the Television Advisory Committee, set up by the Postmaster General to advise on the development of a new television service for the nation, had to choose between Baird’s now 240 line mechanical system and the 405 line Marconi-EMI electronic system. They chose the 405 line system, the system that remained in place until the 1960s when it was gradually replaced by a 625 line system first seen on the new BBC2 channel. Later, of course, digital transmissions began and since October 2012 British television has been completely digital.

The birth of BBC Television

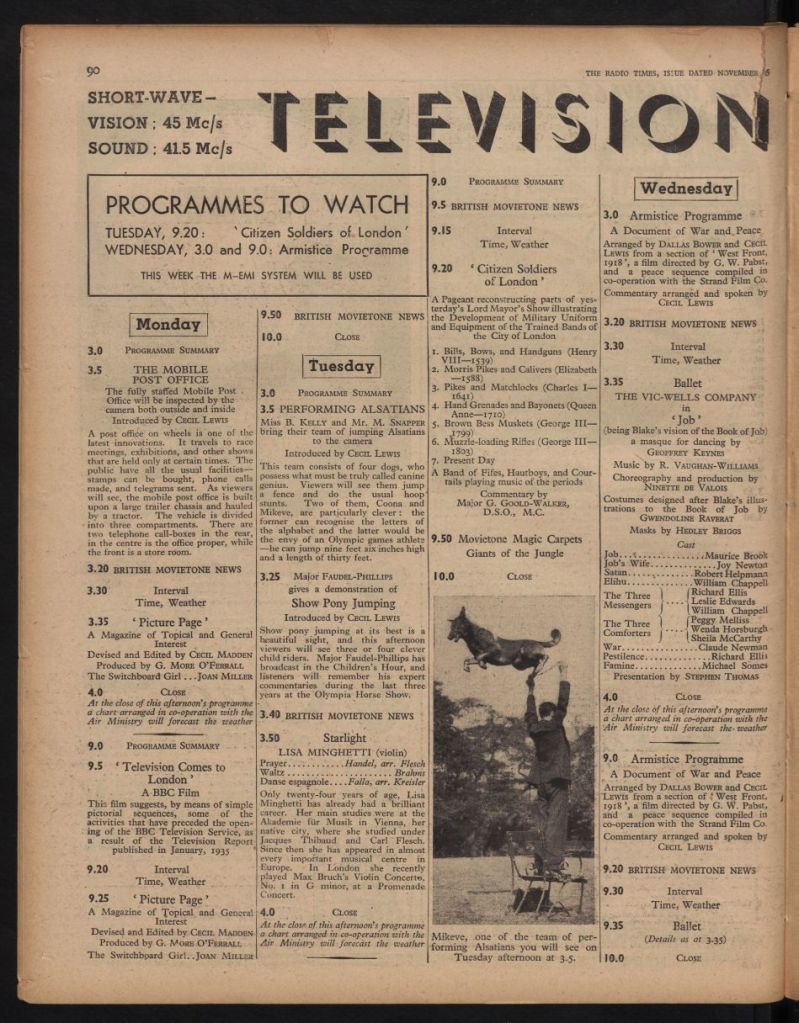

In that earlier blog I described how the nascent BBC’s commitment to both studio and live ‘outside broadcast’ radio transmissions of classical music and opera fitted very well with John Reith’s maxim that the corporation should ‘inform, educate and entertain’. A similar imperative was in play in 1936 when in November of that year the BBC, following the recommendations of the Television Advisory Committee, set up its first television channel. First transmissions from their new studios at Alexandra Palace took place on November 2nd, and the first ‘classical’ music to be heard on the new channel came three days later on November 5th in a dance performance by The Mercury Ballet. This was a company set up by Marie Rambert, a former dancer in Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, who had assisted Nijinsky in the first scandalous performance of The Rite of Spring in 1913. By the 1930s she was living in London with her husband Ashley Dukes and had set up this company, the forerunner of the Ballet Rambert and the present day Rambert Dance Company. The programme included dance set to music by Warlock, Tchaikovsky, Handel and others, some choreographed by the young Frederick Ashton.

The first formal classical music recital was given on November 10th when the 24 year old Austrian violinist Lisa Minghetti, who later made a career for herself in Hollywood, appearing on soundtracks of films as diverse as North by Northwest, Ben Hur and The Fastest Gun Alive. At this time, however, she was largely known as a classical soloist, and had recently played Bruch’s First Violin Concerto at the Proms. Within this recital she performed works by Handel, Brahms and Manuel de Falla.

Below you can see this recital listed within the first ‘Television’ edition of the Radio Times. You can sense the ‘inform, educate and entertain’ mantra coming through loud and clear, with the recital accompanied by programmes on the Post Office, performing dogs, Show Jumping, the Lord Mayor’s Show and commemorations of the Armistice. Continuing the early dance theme, there were also two performances of Ninette de Valois’ Job, set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams and performed by members of the Vic-Wells Ballet, the direct descendant of which is the modern day Royal Ballet.

It’s probably no coincidence that these were the sort of performances that were considered to be suitable for the new television channel. They may have thought that dynamic dance performances would show off the capabilities of the new medium than a static music performance, and where such a performance was transmitted it helped that, judging by her surviving photographs and portraits, Lisa Minghetti most definitely had a face for television!

The new television channel slowly grew in popularity with, for example, 9,000 television sets being purchased in advance of King George VI’s coronation in 1937, but with the outbreak of war in September 1939 the service was closed down. It would be almost seven years before transmissions resumed in June 1946, four years beyond that before the Hallé Orchestra first appeared and a further 14 before the Hallé Choir did the same.

Within the remainder of this blog I will introduce you to the choir’s many appearances on television from 1974 onwards. It is difficult to be certain of the exact number of appearances the choir has made but I hope I have captured the majority of them. They demonstrate the rich variety of music the choir has performed ever since they were first formed in 1858, from simple folk song arrangements and Christmas carols to the major choral symphonic works. The blog may take some time to consume as I have included links to excerpts from many of the broadcasts on YouTube and in a few cases links to complete performances. If any reader has any information on other television appearances that I may have missed I would love to hear from you. I will amend the blog as required to include anything interesting.

The Orchestra Debuts

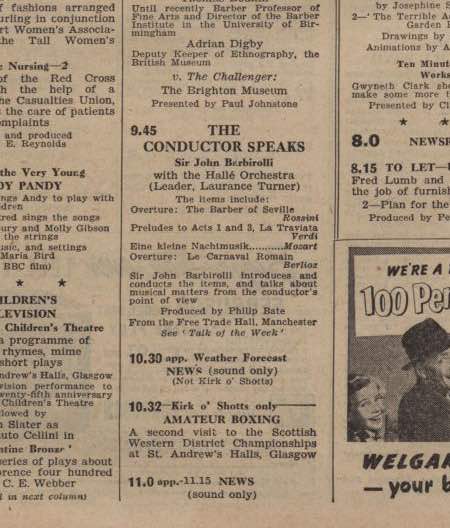

1952 was an important year for the Hallé Orchestra. It saw the release of its first LP record, a recording of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake music and also its first proper appearance on television. Two years earlier, in 1950, the orchestra were in a programme about the documentary film A City Speaks, playing Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries on the soundtrack of the film, and later that same year Arthur Percival, sub-leader of the orchestra appeared in a short programme in which he gave, to quote the Radio Times, ‘some light-hearted impressions of famous conductors under whom he has played.’ However, the programme on November 20th, 1952, relayed from the Free Trade Hall, was the first time the orchestra had appeared performing in person. The programme, part of a series entitled The Conductor Speaks, showed the orchestra playing music by Rossini, Verdi, Mozart and Berlioz, with the pieces introduced by their chief conductor Sir John Barbirolli. Michael Kennedy makes the point that such performances on television by Barbirolli and others were important in bring classical music to a wider audience:

By the intimacy of this medium and its immense popularity it could truly be said that names such as Sargent, Barbirolli, Beecham, became in the truest sense household words, and the great orchestras were brought to the firesides of the people.

Excerpt from The Hallé Tradition – A Century of Music by Michael Kennedy

The Hallé Orchestra continued to appear on TV throughout the rest of the 1950s and 1960s – many appearances at the Edinburgh Festival, a celebration concert for the orchestra’s centenary in 1958, many concerts in the ‘International Concert Hall’ series, and a programme with Jacqueline du Pré playing Bruch’s Kol Nidrei to mark the opening of the new BBC Two channel in Lancashire – all with John Barbirolli at the helm, but never with the choir in tow. In 1965 Melvyn Bragg produced and directed J.B., a programme about Barbirolli as part of the long-running Monitor strand of documentaries. Though it included the Hallé, the orchestra of the Royal Manchester College of Music and members of the Hallé Concerts Society, even here there was no involvement from the choir.

The Owain Arwel Hughes Years

It wasn’t until James Loughran, Barbirolli’s successor as chief conductor of the orchestra, took over that the choir made its television debut. This could have been on February 10th, 1974 when The Times advertised the ‘Hallé Chorus’ as appearing alongside the Leeds Festival Chorus and the Glasgow Phoenix Choir in a programme in the Masters of Melody series that had started the previous year. This was a programme of popular sacred vocal music produced for Yorkshire TV by Jess Yates, more famous for his long-running Stars on Sunday programme. Given the programme only ran for 20 minutes and also included Canadian soprano Barbara Shuttleworth I can only think that the choir made but a brief contribution. Even that may be in doubt, given that the official ITV Archive listing of the programme mentions the two other choirs and Barbara Shuttleworth but not the Hallé Choir. If any reader knows for certain if the choir appeared on this programme I would love to hear from you.

What is certain is that on October 6th, 1974, in a BBC Two programme introduced by John Amis, a veteran presenter of classical music on radio and TV and regular panel member on Radio 4’s My Music, the women of the choir sang the wordless chorus in a Loughran performance of Holst’s The Planets. Given the offstage nature of this chorus, however, this was probably not an ‘appearance’ as such, but more of a ‘contribution’! The choir’s first true appearance on television alongside the orchestra would take place the following year, thanks to a conductor with whom they would go on to make three substantial appearances on BBC Two, Owain Arwel Hughes.

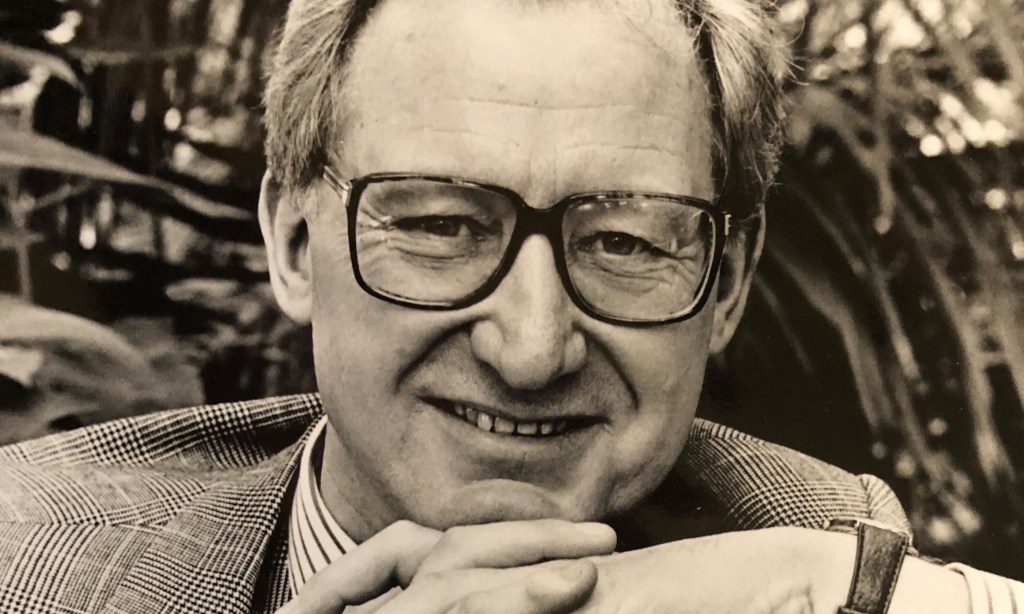

Owain Arwel Hughes, born in 1942 in the Rhondda valley, trained as a conductor under Adrian Boult and Bernard Haitink, and went on to have a long association with the Hallé from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s. Indeed a whole chapter in his autobiography My Life in Music is devoted to his relationship with the orchestra. Still very much active today coming up to his 83rd birthday, he is also notable for being the cousin of one of the Bass members of the Hallé Choir! His first concert with the Hallé was in Nottingham on September 1st, 1973, a performance that included Brahms’ Fourth Symphony.

In his autobiography Hughes describes how in 1975 his relationship with the Hallé came to embrace television. He was contacted by Herbert Chappell, a musician and composer but also active as a producer and director of classical music programming on BBC Two. Chappell had been recruited to the BBC by Huw Wheldon, then managing director of BBC TV, but previously the editor and presenter of the Monitor programme for whom Melvyn Bragg had made his Barbirolli documentary 10 years earlier. Chappell, knowing of Hughes’ work with choirs, suggested that they collaborate on an hour-long programme based around English choral music. This would be presented within the context of a working rehearsal involving choir, orchestra and various soloists, as Hughes explains:

Bert [Chappell] had become acquainted with my work with choirs, and proposed that I present and conduct an hour-long programme on the development of the English choral tradition. This, we decided, should not be done in the formal, documentary, talk to camera format, but that I would demonstrate, through rehearsing a choir and orchestra, how styles, techniques, and compositions had evolved over time… It was an innovative way of describing musical, historical progression, typical of the televisual imagination of Bert, and the orchestra and choir responded enthusiastically to the challenge.

Excerpt from Owain Arwel Hughes – My Life in Music

It was indeed innovative, and probably unlike anything that has been seen on TV before or since. Alongside the orchestra in the Free Trade Hall were the choir, trained here as for all of the choir’s TV appearances over the next 20 years by the redoubtable Ronald Frost, and a stellar quartet of soloists – Sheila Armstrong, Bernadette Greevy, Ryland Davies and Alan Charles. The works covered were five of the great warhorses of the English choral tradition, Handel’s Messiah, Mendelssohn’s Elijah, Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast and Britten’s War Requiem. The concept worked in practice exactly as Hughes described above, with him rehearsing particular passages from each of the five works and stopping when he felt corrections were needed, often to the exasperation of choir, orchestra and soloist alike! It’s is difficult to imagine anyone successfully pitching a similar idea to a TV producer today, especially as in the end it was nearer 75 minutes long than an hour, but as a record of how a choral/orchestral sound is honed in rehearsal prior to a performance it is an invaluable record, even if it ended up a little artificial.

The programme was aired under the title of Make A Joyful Noise (a quote from Belshazzar’s Feast) on BBC Two at 8.15pm on Sunday, September 28th, 1975. The clip below is an example of how it looked. Hughes is rehearsing the Baal section from Mendelssohn’s great High Victorian masterpiece Elijah. After countless stops and starts and the occasional face swab he runs the passage through without interruption. The whole process takes over 23 minutes of television.

If any viewer was frustrated by the stop-start nature of Make A Joyful Noise, they would have been gratified a few weeks later on October 19th, again on BBC Two, when the choir gave a complete performance of Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast with the baritone soloist Alan Charles. Hughes was pleased with the result, writing in his autobiography that ‘the orchestra tackled the technical difficulties of Walton’s score with bravura, and the choir, as a result of the unselfish, thorough training by the chorus master, Ronnie Frost, was stunning in its precision, accuracy and conviction.’

As I have mentioned in previous blogs, Belshazzar’s Feast was something of a party piece for the Hallé Choir at this time, regularly cropping up in concert listings and also a piece recorded by the choir for the Classics for Pleasure label. It was in the choir’s blood, a fact obviously picked up by the composer himself. As part of the programme William Walton had come across from his home in Ischia to be interviewed by Humphrey Burton about the work. In a studio in London Burton and Walton sat through the recording of the performance. Hughes describes what happened next:

The work came to its shattering, cataclysmic conclusion, and Burton, with no preamble, went straight for the jugular, and asked Walton what he thought of the performance. With tears running down his face, he declared it to be the best performance he had ever heard of the work.

Excerpt from Owain Arwel Hughes – My Life in Music

Here is that complete performance:

A couple of years later in 1977 Hughes was asked by Welsh rugby legend Cliff Morgan, then head of the BBC’s television Outside Broadcast unit, to put together a televised choral extravaganza in the Royal Albert Hall to celebrate Queen Elizabeth’s Silver Jubilee. Out of this concert came the germ of an idea for an ongoing series and Hughes worked with John Vernon, who had produced and directed the Jubilee show, to bring it to fruition. Hughes describes the idea thus, a series of concerts from around the country featuring the various regional symphony orchestras in programmes that would include ‘descriptive orchestral items, a variety of singers in excerpts from opera, movements from concertos, and choirs singing highlights from opera and oratorio.’

The programme was eventually realised under the title The Much Loved Music Show. I described in a previous blog how in 1984 the concept eventually spawned a recording for Classics for Pleasure featuring the Hallé Orchestra and Choir. The Hallé’s episode of the programme itself, filmed at the Free Trade Hall in 1980, was broadcast on BBC Two on January 11th, 1981. In it the orchestra were joined by the choir, and soloists Linda Esther Gray and Robert Tear, in works by Bach, Bizet, Handel, Lalo, Massenet, Tchaikovsky, Verdi and Wagner. Hughes introduced each piece to camera much in the style of André Previn’s Music Night from a few years earlier. In the clip below he introduces the final two choruses from Handel’s Messiah, Worthy is the Lamb and Amen.

As with André Previn’s earlier series, The Much Loved Music Show provided a mainstream peak-time outlet for classical music. In his autobiography Hughes considers what he believes were its beneficial effects:

It proved there was a love and need for classical music, and I’ve been assured by countless people, the public and professionals alike, that we not only popularised classical music, but opened the eyes and ears of many to its abundant riches and hidden treasures. I am told that a happy consequence of this exposure was to increase the numbers attending live concerts, a timely boost for orchestras struggling to maintain audiences.

Excerpt from Owain Arwel Hughes – My Life in Music

Primetime Hallé Choir

The choir’s appearance on The Much Loved Music Show early in 1981 was one of a plethora of TV appearances that the choir made at the beginning of the 1980s, a period in which the choir entered the mainstream of television broadcasting in way that would be unlikely today. Take for example the choir’s appearances on the Russell Harty Show, a chat show broadcast at a prime mid evening slot, first on BBC Two and later on BBC One. One could not envisage the present-day choir being invited to perform on The Graham Norton Show or The One Show, the nearest equivalent BBC programmes today.

Born in Giggleswick in 1934, Russell Harty worked briefly as an English and Drama teacher before entering the world of broadcasting, initially as a producer for BBC Radio 3. Following a series of interviews conducted for the ITV arts programme Aquarius, he got his own chat show on ITV in 1972, moving to the BBC in 1980, where in November he encountered his nemesis in his much-clipped interview with the extremely recalcitrant model/singer Grace Jones. One month later, in an episode broadcast from Manchester just before Christmas, he appears to be having further problems (this was of course a live programme) when an apparent ‘technical problem’ arises. In an obviously well-rehearsed ad-lib he asks the well-dressed audience if anybody can sing. One gentleman pipes up that yes, he can as long as he is given a B flat. The studio piano does the honours and suddenly the whole audience bursts into a rendition of Ding, Dong, Merrily on High! The studio audience was of course composed entirely of members of the Hallé Choir, and though the term itself was not coined until 2003, this must the first broadcast example of a ‘Flash Mob’. See the whole sequence for yourself in the clip below:

Remarkably, the choir made two further Christmas television appearances during December 1980. They made what choir member Chris Hughes remembers as being a ‘very cold’ recording of Christmas music in Lincoln Cathedral which was broadcast on ITV on 21st December. The programme also featured the Hallé Orchestra, Cantabile, the singer Sandra Browne, the actor Peter Barkworth doing some readings, the Fanfare Trumpeters of the Band of the Royal Air Force and Lincoln Cathedral Choir. The conductor was Peter Knight, also a composer and arranger, known for his orchestrations for the Moody Blues’ 1967 hit Nights in White Satin, The Carpenters’ Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft, and the films Tess, Quest for Fire and The Dark Crystal. The video below is a compilation from the programme, which was titled Joy to the World, including that carol itself, Calypso Carol, The Virgin Mary had a Baby Boy with Sandra Browne, John Rutter’s Nativity Carol and Hark the Herald Angels Sing.

Given the choir also had their annual performance of Messiah and their regular Free Trade Hall Christmas concerts at this time, they must have had a very busy December. And they were not done, as they also performed with the Besses o’ th’ Barn band, children of Parkhill Primary School, Toxteth on a Granada Reports Christmas Eve special live from Exchange Flags in the middle of Liverpool, conducted by Ronald Frost. In the clip below you can hear the assembled forces singing O Come All Ye Faithful, Once in Royal David’s City, a repeat performance of the Calypso Carol, and Ding, Dong, Merrily on High.

The choir’s run of primetime TV appearances culminated in a repeat performance on Russell Harty’s chat show early in 1981. As Russell Harty says in the clip below, the choir reconvened and ‘dropped their cloak of anonymity’ to perform two folk song arrangements conducted by Ronald Frost. The first of these is an arrangement of Bobby Shaftoe by the North Eastern composer W.G.Whittaker, whose work they would go on to record two years later, and the second an arrangement of Polly Wolly Doodle by Stanford Robinson. What to me is remarkable about both these performances and the Christmas performance from a few months earlier is that the choir perform sitting down!

In my blog about the Hallé Choir’s relationship with the BBC Proms I recounted how, owing to the BBC Symphony Chorus being unavailable, James Loughran, the conductor for the 1981 Last Night of the Proms, invited his own Hallé Choir down to London to take their place. I will refer you to that blog for more details and personal reminiscences of that occasion, suffice to say that it concluded a couple of remarkable televisual years for the Hallé Choir. In the first half of the concert the choir again performed Belshazzar’s Feast but in the clip below you can hear Richard Baker introducing the final sequence of the concert including Jerusalem, James Loughran’s speech where he explains why the Hallé Choir are present, Auld Lang Syne and the National Anthem.

The Azores Trip

The December 1988 edition of the Hallé Concerts Society newsletter, Hallé News, contained a fascinating article by the Hallé Choir’s chairman, Bill Golightly, that included mention of possibly the most unusual television appearance the choir has ever made. The article was about a trip members of the choir took in September 1988 to the Portugese islands of the Azores, far out in the Atlantic Ocean. The Manchester Camerata had been invited to perform at the 5th International Musical Festival of the Azores. To provide vocal accompaniment some 40 members of the Hallé Choir, prepared by Ronald Frost, were also invited along. The idea was that the would perform three concert programmes on the main islands of San Miguel and Terceira, with a repertoire of unaccompanied British part-songs, opera choruses by Bizet and Donizetti, motets by Stanford and the Mozart Requiem. The unaccompanied items were to be conducted by the choir’s assistant Chorus Master Russell Medley and the orchestral items by Manfred Ramin.

The trip began in Terceira and the last of the three concerts there took place in the island’s cathedral in front of an enthusiastic audience of three thousand. The concert was broadcast on Azorean TV and remarkably a choir member managed to obtain footage of the broadcast. In the slightly scratchy but remarkably evocative clip below you can hear the choir performing the opening movement of the Mozart Requiem.

After Terceira the choir and orchestra moved on to the main island of San Miguel and the capital city of Ponta Delgada, where they performed the same three concerts. The first concert was again recorded, this time for Portugese TV, but the final concert produced the biggest drama of the tour. It’s not particularly pertinent to the theme of this blog, but worth recounting as it shows how the choir often triumph in adversity! Here is Bill Golightly’s description of what happened:

At the local theatre the stage was rather small and so a choir platform was constructed. Half-way through our first opera chorus there was a cracking and a rumbling. The Tenors and Sopranos slid one way and the rest of the Choir the other. Some went down on their knees, but like true Hallé Choir members we never stopped singing. We rose to our feet, finished the chorus, and fled before anything else happened! Needless to say the platform was disassembled, and we resumed, unscathed, to rapturous applause.

Bill Golightly writing in Hallé News, December 1988

New Beginnings – The Bridgewater Hall

The next television appearance that I’ve been able to uncover was ten years later and came two years after the Hallé Choir and Orchestra moved into their new performing home, the Bridgewater Hall. It was another unusual occasion and possibly unique in the history of the Hallé as it saw both the Hallé and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and their respective choirs joining together for a grand Gala Concert as part of Granada TV’s Live Challenge ’99 initiative. The concert was to be conducted by the American-born conductor and composer Carl Davis, who around that time was well known for his collaborations with both orchestra – he had recently collaborated with Paul McCartney on the Liverpool Oratorio for the RLPO and would soon be recording a CD of Christmas music with the Hallé Orchestra and Choir.

The concert took place in November 1998 at the Bridgewater Hall and was recorded by Granada TV for later broadcast under the title Battle of the Bands. It was certainly a star-studded occasion. The coverage was introduced by Matthew Kelly, who began his career as an actor in the repertory company of the Gateway Theatre in nearby Chester but was best known by then as the host of ITV’s Stars In Their Eyes. The stage introductions were made by Richard Madeley and Judy Finnegan, aka Richard and Judy, then riding high in the ITV firmament, and the concert was attended by many actors from the Granada stable, some of who were interviewed during the programme.

The clip below includes some of the highlights from the programme, with the combined choirs singing the Polovtsian Dances by Borodin and accompanying tenor Dennis O’Neill in Di Quella Pira from Verdi’s opera Il Trovatore. It was obviously quite the occasion!

Songs of Praise is a British TV Sunday institution, wherein an enthusiastic audience, usually in a church or cathedral setting, gather to sing popular hymns with gusto. Many amateur choral singers over the years have been roped in to supplement the singing strength, especially as ‘popular’ hymns become less and less well known by the general public – I myself have twice sung in two editions of the programme recorded in Chester Cathedral.

On December 9th, 2001 the programme came not from an ecclesiastical location but from the Bridgewater Hall with the Hallé Orchestra providing the music, conducted by long-standing Songs of Praise musical director Paul Leddington Wright, and the Hallé Choir bolstering the congregational singing and performing some items of their own. Also in the programme, introduced by Aled Jones, were 13 year old soprano Becky Taylor and the young tenor Russell Watson, then at the height of his crossover fame.

Given the date of broadcast early in Advent, there was a definite Christmas theme to the music chosen for the programme. In the clip below you can see Aled Jones introducing the choir’s rendition of And the Glory of the Lord from Messiah, and the choir leading the congregation in the singing of Hark the Herald Angels Sing.

Proms Plus

From this point onwards, as the BBC’s classical music output on television began to dwindle and ITV’s disappeared completely, the choir’s appearances began to be limited to the BBC Proms. Over the last 20 years four of their Proms appearances have been televised, and they have served to emphasise, if emphasis were needed, the legacy Sir Mark Elder has left the orchestra and choir as he has handed over the reins to Kahchun Wong.

The first of these appearances was a seminal one, a case of Sir Mark declaring to a general audience the importance of Edward Elgar in his vision for both the Hallé and the Hallé Choir. It was the 2005 performance of the Dream of Gerontius, which led a couple of years ago to a recording of the work, the first of three recordings of the major Elgar oratorios that all won awards. In this performance the soloists are Alice Coote, Paul Groves and Matthew Best, though Matthew Best was replaced by Bryn Terfel for the later recording. The part of the semi-chorus is taken by the then recently formed Hallé Youth Choir, a further statement of the importance Sir Mark gave to the development of young voices in his Hallé vision. Below you can see the complete performance.

A second televised Proms performance for both the Hallé Choir and the Youth Choir followed four years later, a performance of Mendelssohn’s Second Symphony ‘Lobgesang‘, performed as part of the Mendelssohn bi-centenary celebrations. I described in my blog ‘The Hallé Choir and the Proms’ how the choir had trialled the work in Valencia, Spain, where the orchestra had travelled to perform all of Mendelssohn’s symphonies, and also how the Proms performance was James Burton’s swansong as choral director of the Hallé. You can see from the performance below, what sort of a legacy Burton left behind him:

The one non-Proms television appearance by the Hallé Choir in the last 20 years came in 2015. The BBC had recently launched the Ten Pieces initiative to introduce schoolchildren to the sound of classical music. The idea was to take ten pieces of classical music, some popular, some not so, some old, some new, and parcel them up in easily digestible chunks wrapped in a pop video-style setting, and both present them directly to schools and show them on the CBBC channel. The initiative continues to this day – a further set of ten pieces all written by women composers has recently been recorded, conducted by Ellie Slorach.

This particular set was recorded by the BBC Philharmonic conducted by Alpesh Chauhan, at the time the assistant conductor for the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and now very much an established conductor in his own right. It included pieces such as Vaughan Williams’ The Lark Ascending, Wagner’s The Ride of the Valkyries and Gabriel Prokofiev’s Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra. The choir’s contribution was an edited version of the Dies Irae and Tuba Mirum sections of Verdi’s Requiem. The music itself was recorded in a session at the BBC Philharmonic studio at MediaCity in Salford.

For the video element the choir and orchestra decamped to Victoria Warehouse, a popular clubbing venue in Salford close to the Old Trafford football ground. It was an interesting experience. The music already having been recorded, both orchestra and choir had to effectively mime to the pre-recorded sound whilst they were being filmed. As the choir had to appear without scores, they had to learn the notes as if they were going to sing them from memory and then hopefully move their mouths in sync with the recorded sound. It proved difficult for some (including me!) but the end result was extremely effective. In the video below you can see how it was eventually packaged up for the young audience.

There are just two televised Proms appearances to describe to bring the story up to date. The first was the first Proms performance of Vaughan Williams’ visionary oratorio Sancta Civitas which the choir gave in 2015, joined again by the Hallé Youth Choir and also by the London Philharmonic Choir. Whilst the second half of the concert, a performance of Elgar’s Second Symphony, was broadcast on BBC Four, the performance of the oratorio in the first half was deemed by the powers that be only to be suitable to be made available on the BBC iPlayer. This was a shame, as it is a magnificent work, sadly yet to receive a Manchester performance by the choir. You can see the whole performance in the clip below:

Finally, there is the work that Sir James Macmillan wrote for Sir Mark Elder’s farewell performances in Manchester as musical director and which was then reprised at the 2024 BBC Proms, Timotheus, Bacchus and Cecilia a setting of words from John Dryden’s Alexander’s Feast. This section of the blog is by way of an addendum to my blog ‘Sir Mark Elder and the Hallé choral revolution’, suffice to say this was an extremely fitting way to mark the end of Sir Mark’s tenure, involving as it did not just the Hallé Choir but two symbols of that revolution, the Hallé Youth Choir and the Hallé Children’s Choir. Both of the Manchester concerts were real Bridgewater Hall occasions (though sadly I had to miss both of them) and the Proms performance in the Royal Albert Hall took the piece to another level, as can be seen in the video below:

So that is the story so far as regards the Hallé Choir and television. One hopes it is not the end of the story but the omens are not good. The BBC used to regularly broadcast concert performances from places like the Royal Festival Hall, and broadcast opera and ballet from Covent Garden, and until recently would produce regular documentary series on classical music themes, but now, in the words of Roderick Williams in a recent podcast, it’s largely ‘The Proms and Gareth Malone’. The cellist Julian Lloyd Webber wrote a scathing piece in the Radio Times in November 2022 that drew attention to the decline in the BBC’s television coverage of classical music.

Let’s look at some facts. When Covid struck and lockdowns became the norm, people turned to music as never before. All over the world, radio stations and streaming services reported vastly increased numbers of listeners to music – and especially to classical music. It became a solace, a bedrock for people at the time of their greatest need. All too often, music is taken for granted, regarded as something “nice to have” but not essential. This is a nonsensical point of view as, in monetary terms alone, music is essential to the UK economy, contributing an extraordinary £5.8 billion in the year before the Covid-enforced shutdown. Yet I believe that the true value of music lies in how it speaks to us and how it can inspire us. Music knows no barriers of language, race or social background. Music unites us – and in these troubling times, it matters more than ever, as it reminds us what it means to be human. So, please, let’s bring back music to our classrooms – and our television screens.

Julian Lloyd Webber writing in the Radio Times, November 22nd, 2022

I hope it’s not too late to stop that decline and for the BBC to resume its mission to ‘inform, educate and entertain, and also that ensembles like the Hallé Orchestra and the Hallé Choir continue to grace the nation’s television screens for many years to come.

References

William Golightly, “Hallé Choir in the Azores”, Hallé News (December 1988).

Owain Arwel Hughes. Owain Arwel Hughes : My Life in Music, (Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru / University of Wales Press, 2012). ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uocuk/detail.action?docID=1035157.

Julian Lloyd Webber, “Bring Back Classical Music TV”, Radio Times (November 22nd 2022).

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition – A Century of Music, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

Simon J. Potter, This is the BBC: Entertaining the Nation, Speaking for Britain, 1922-2022 (Oxford University Press, 2022; online edn, Oxford Academic, 21 Apr. 2022.

A Short History of Television (Dock10) https://www.dock10.co.uk/about/news/a-short-history-of-television/

BBC Genome Project https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Times Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

ITV Archive

The Television & Radio Index for Learning and Teaching https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/trilt/

Thanks especially to the choir members who provided clips and additional information

Leave a comment