In a previous blog I described how in his nearly 25 years at the helm of the Hallé Orchestra Mark Elder revolutionised the choral landscape in Manchester with the pyramid of choirs he helped set up, at the top of which is the choir that Charles Hallé set up all those years ago and that bears his name. With Elder’s last performance with the orchestra at the Edinburgh Festival in August 2024 a new era began as from the start of the 2024/25 season the Singapore-born conductor Kahchun Wong became the new chief conductor of, and artistic advisor to, the Hallé. Though he had conducted the Hallé Choir in a performance of Fauré’s Requiem the previous season, it was surely a statement of intent that his first two appearances with the choir in his new role would be two of the big-hitters of the symphonic choral repertoire, Beethoven’s 9th Symphony, which will be performed at the end of the season, and Mahler’s mighty 2nd Symphony, the so-called Resurrection Symphony, which the orchestra, Hallé Choir and Hallé Youth Choir performed on January 16th of this year. To mark the Mahler performance I thought I would look at the choir’s early history with this remarkable symphony.

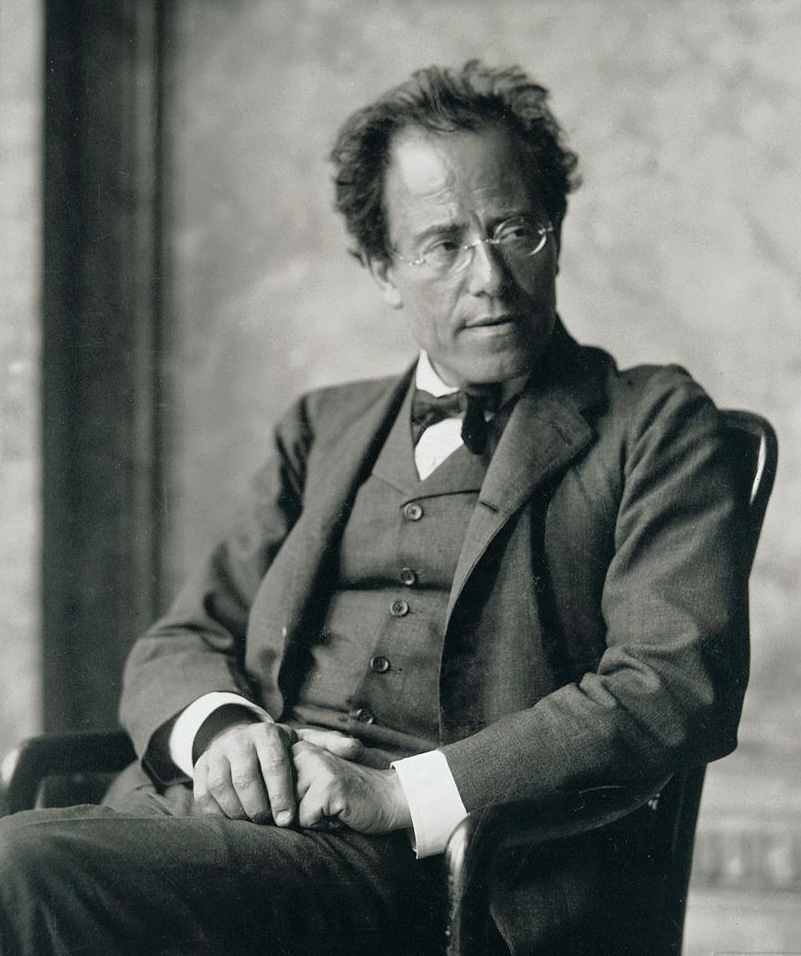

Gustav Mahler is now widely regarded as one of the greatest symphonists of the late Romantic era, his symphonies programmed regularly by all the major orchestras, including the Hallé. However, it was not always thus, as we shall see.

Mahler was born in 1860 into a Jewish family in what is now the town of Kalište in the Czech Republic but which was then the German-speaking Bohemian town of Kalischt. Mahler studied music in Vienna before taking up conducting posts in Budapest and Hamburg, and in 1897 became director of the Court Opera in Vienna. It was as a conductor that he was best known during his lifetime, but when time would allow he would compose, often in summer breaks from his conducting duties, specialising in song cycles and particularly the sequence of large-scale symphonies that began with the 1st in 1889. He was a complicated person, riven by a self-doubt that was exacerbated by his own fragile health, and by the hostility and prejudice that he suffered because of his Jewish origins. He had to formally convert to Catholicism in order to take up the post in Vienna, and continued prejudice forced him to resign from that post in 1907. He then moved to New York to work with the Metropolitan Opera and later to lead the New York Philharmonic (a role later occupied coincidentally by one John Barbirolli). In his symphonies we see this uncertainty and doubt, as well as Jewish and Austrian musical influences, all wrapped in lengthy musical reflections on the human conditions and man’s place in the cosmos. As he himself said: ‘The symphony must be like the world. It must embrace everything’.

Though his music continued to be performed following his early death at the age of only 51 in 1911, particularly in Vienna, his music was often not held in high regard by the musical establishment, his symphonies considered too sprawling, too repetitive, too brash and vulgar for frequent consumption. Intertwined with this from the 1920s onwards, inevitably given the nature of the times, was a tide of Germanic anti-semitism that harked back to Wagner and forward to the Nazis. This extract from the entry on Mahler in The Musical ABC of Jews, published in Munich in 1935, is typical of this sentiment and how it affected Mahler’s standing: ‘By always hankering after empty effects, his works are as quintessentially Jewish as his ancestry.’ Even in Britain, as sympathetic a fellow composer as Ralph Vaughan Williams, even though some believed he had a sneaking regard for Mahler’s music and did not have an anti-semitic bone in his body, felt moved to make the following barbed compliment about Mahler’s music in one of his essays: ‘Intimate acquaintance with the executive side of music in orchestra, chorus and opera made even Mahler into a very tolerable imitation of a composer.’

The standing of Mahler’s music is reflected in the performance history of Mahler’s symphonies in Manchester as summarised in the table below. None of the symphonies were performed by the Hallé in Mahler’s lifetime, the performance nearest to being contemporaneous being that of the 1st Symphony, conducted by Michael Balling in 1913, and even that did not receive its second performance for another 42 years. In the 1920s and early 1930s Hamilton Harty conducted complete performances of the 4th and 9th Symphonies, the Adagietto from the 5th Symphony, the unfinished elements of the 10th Symphony, and Das Lied von der Erde, a symphony in all but name, but all would have to wait until after the Second World War for their second performances. Most tellingly, the three choral symphonies, numbers 2, 3, and 8, would have to wait until, respectively, 1958, 1967 and, incredibly, 1996 for their first complete Manchester performances.

| Symphony | Premiere | 1st Hallé Performance | 2nd Hallé Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number 1 (Titan) | 20 November 1889 | 30 January 1913 | 16 November 1955 |

| Number 2 (Resurrection) | 13 December 1895 | 14 May 1958 | 15 May 1958 |

| Number 3 | 9 June 1902 | 10 May 1967 | 11 May 1967 |

| Number 4 | 25 November 1901 | 24 November 1927 | 12 November 1947 |

| Number 5 (Adagietto only) | 18 October 1904 | 18 October 1923 | 2 October 1946 |

| Number 5 (Complete) | 18 October 1904 | 13 April 1966 | 14 April 1966 |

| Number 6 (Tragic) | 27 May 1906 | 5 May 1965 | 6 May 1965 |

| Number 7 | 19 September 1908 | 19 October 1960 | 19 October 1960 |

| Number 8 (Symphony of a Thousand) | 12 September 1910 | 29 September 1996 | 3 October 1996 |

| Das Lied von der Erde | 20 November 1911 | 11 December 1930 | 9 April 1946 |

| Number 9 | 26 June 1912 | 27 February 1930 | 24 February 1954 |

| Number 10 (unfinished version) | October 12 1924 | 29 November 1961 | 30 November 1961 |

Part of the revival of interest in Mahler’s music after the Second World War was driven by the German-born conductor Bruno Walter, who had assisted Mahler with some of his later compositions and conducted the premieres of Das Lied von der Erde and the 9th Symphony after Mahler’s death. He conducted the first recordings of both of these pieces in Vienna in the 1930s before, as a Jew following the anschluss, he was forced into exile, eventually settling in the United States. During the 1950s he made a series of important recordings of the Mahler symphonies that were crucial in re-establishing public interest in his music, or in many cases establishing such interest for the first time. For example, I remember my teenage brother in the late 1960s buying Walter’s recording of the 5th Symphony and waxing lyrical about it, though I at that point still really didn’t understand the attraction! This revival of interest was in no small measure also helped by the inclusion of the now famous Adagietto from the 5th Symphony in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 adaptation of Thomas Mann’s novella Death in Venice. Mahler’s symphonies are now a staple part of any orchestra’s season, and barely a Hallé or BBC Proms season goes by without at least one Mahler symphony being programmed.

Important in the revival of interest in Mahler’s music in Manchester in the 1950s and 1960s was the Hallé’s chief conductor Sir John Barbirolli. Michael Kennedy’s biography of Barbirolli explains that the conductor’s attention was brought to Mahler by the cricket-loving music critic of the Manchester Guardian, Neville Cardus. Kennedy writes how in recalling Hamilton Harty’s 1930 performance of the 9th Symphony in an article in 1952 Cardus wrote: ‘It is the ideal work for Sir John Barbirolli to conduct. Why has he not been drawn to it these several years?’. Barbirolli had conducted the 4th and 1st Symphonies, the Adagietto, and Das Lied von der Erde in the immediate post-war years but Cardus’ words set in motion an idea in Barbirolli’s mind to cover Mahler’s oeuvre in its entirety. The 2nd Symphony was actually scheduled for the 1952/53 season though later withdrawn because of the cost, but in February 1954 Cardus had his wish when the 9th Symphony had its second Hallé performance with Barbirolli conducting.

Over the rest of the decade and into the 1960s Barbirolli gradually brought all of the symphonies and the orchestral song cycles into the Hallé’s repertoire. The only omission was the mighty 8th Symphony, the so called Symphony of a Thousand, which had to wait until 1996 and the opening of the Bridgewater Hall for its first Manchester performance under Kent Nagano. Presumably this was simply a matter of the cost of putting it on and of Free Trade Hall space constraints.

Kennedy writes how Barbirolli’s preparation for each of the Mahler works was meticulous and time-consuming, with him working for months on each score, bowing the string parts (many of his marked scores for various works can be seen in the Hallé Archive), and translating Mahler’s detailed German instructions into English. He compares Mahler, for whom the intense activity of writing of these scores may have hastened his early death, and Barbirolli, for whom the intense activity of preparing the scores may have done exactly the same. Barbirolli saw in Mahler a kindred spirit. As Kennedy writes: ‘Undoubtedly Barbirolli found in this music not only a marvellous and satisfying challenge to his musical temperament, but he recognised in it the complex humanity of the composer which paralleled his own intricately wrought and volatile nature.’

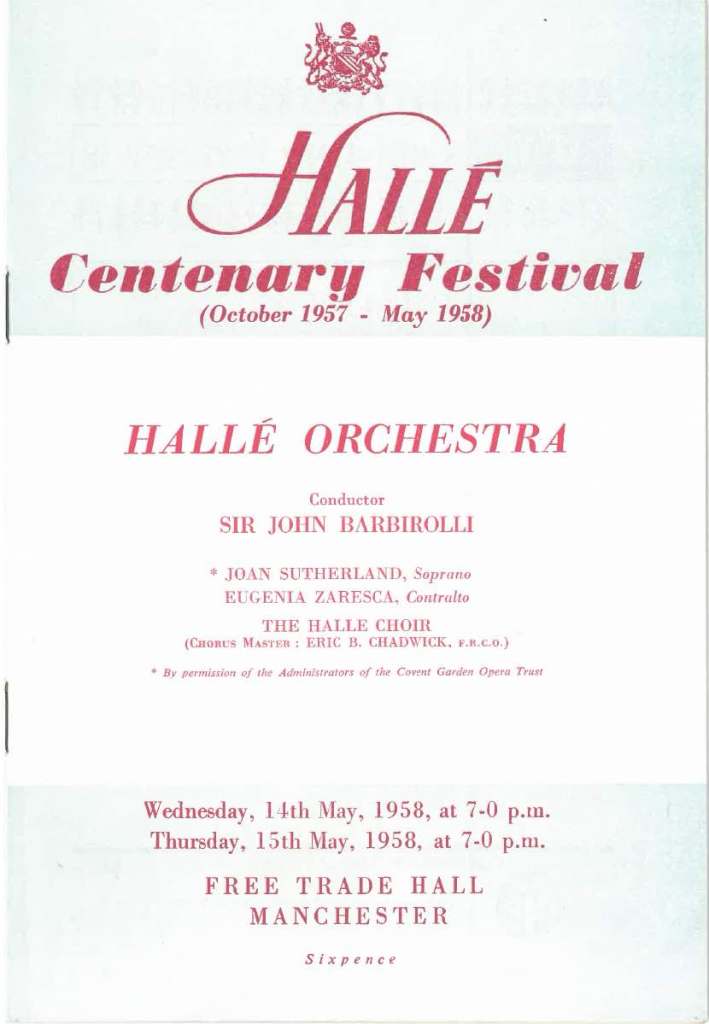

The 2nd Symphony, also known as the ‘Resurrection’ Symphony was finally programmed for the 1957/58 season, the season that marked the centenary of the setting up of Charles Hallé’s orchestra. Barbirolli’s excuse for programming it was boastful, but entirely true given the condition the orchestra was in when he arrived in Manchester in the 1940s: ‘After all, I resurrected the orchestra.’

The symphony itself is now regarded as one of the pinnacles of the orchestral/choral repertoire. It consists of five movements, two long outer movements and three shorter inner movements that act as a kind of intermezzo. The last of the three inner movements is a setting for alto soloist and orchestra of the German folk poem Urlicht (‘Primal Light’) that had originally been part of a larger set of such settings that he called Das Knaben Wunderhorn (‘The Boy’s Magic Horn’). Another Wunderhorn tune appears in the 3rd movement of the symphony, another had appeared in the 1st Symphony and two more were to appear in the 3rd and 4th Symphonies. The long final movement is climaxed by a setting for choir, alto soloist and soprano soloist of a poem by Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock entitled Die Auferstehung (‘The Resurrection’) with added textual interpolations by Mahler himself. The symphony as a whole is a journey from darkness to light, from the funeral march of the 1st movement, through the trials and pleasures of life described in movements 2 and 3, a gradual feeling of relief from worldly woes during the Urlicht movement, and a final triumphant choral coda in the last movement that moves from apocalypse to the final resurrection of all souls (Mahler was insistent that his idea of the resurrection included all souls – there is no sense of judgement in what he depicts). As it moves from an unaccompanied ppp to a blazing fff accompanied by full orchestra, this choral coda, while not especially difficult technically, is one of the most satisfying sings in the entire symphonic choral repertoire. Sadly, because the orchestra required is so large and the choral element is so brief, barely 10 minutes, the work has largely stayed in the domain of professional symphony orchestras. As a footnote, however, I have personally sung in a choral society performance of the work in Chester Cathedral, with an amateur orchestra, that was immensely rewarding – it can be done!

Barbirolli actually began preparing for the Hallé premiere of the symphony in 1956, as evidenced by a letter he sent in October of that year from Italy to Hallé violinist Audrey Napier Smith whilst convalescing after an operation. His words highlight his frequent struggles both with his health and his state of mind, again echoing Mahler:

…I fight hard against this deepening gloom which of course is not restful, and the only real refuge I have is to get to my work. These last few days I have memorised the choral finale of Mahler II (for next season) and that is another little job done. Occasionally the clouds seem to disperse a little and for a few fleeting moments I feel alive again.

Letter from John Barbirolli to Audrey Napier Smith, quoted in ‘Barbirolli – Conductor Laureate’ by Michael Kennedy

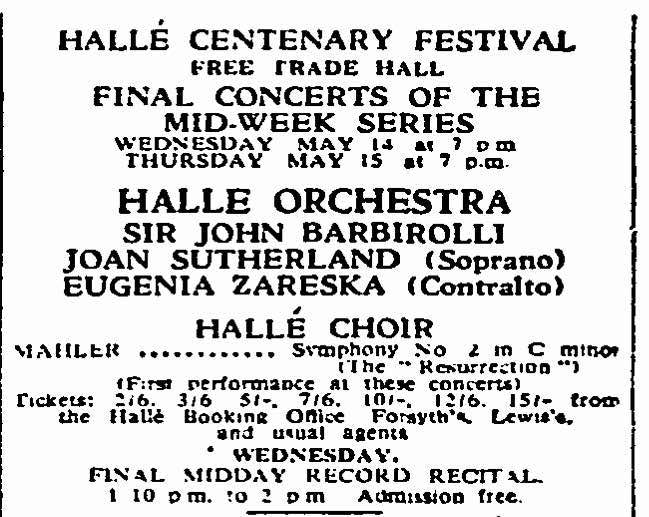

There were to be two performances of the symphony in May 1958, serving to round off the centenary season. It was to be expensive with the two performances costing the sum of £3,500 (£70,000 in today’s money), with even more expense avoided only by thinning out the orchestra (in line with options sanctioned by Mahler) and, for example, having brass players perform both on- and off-stage rather than having separate groupings as is the normal practice. As a result the orchestra ‘only’ numbered 106 players, though it has to be said that the orchestra for Kahchun Wong’s performance in January 2025, even with a separate off-stage band, only numbered 8 players more.

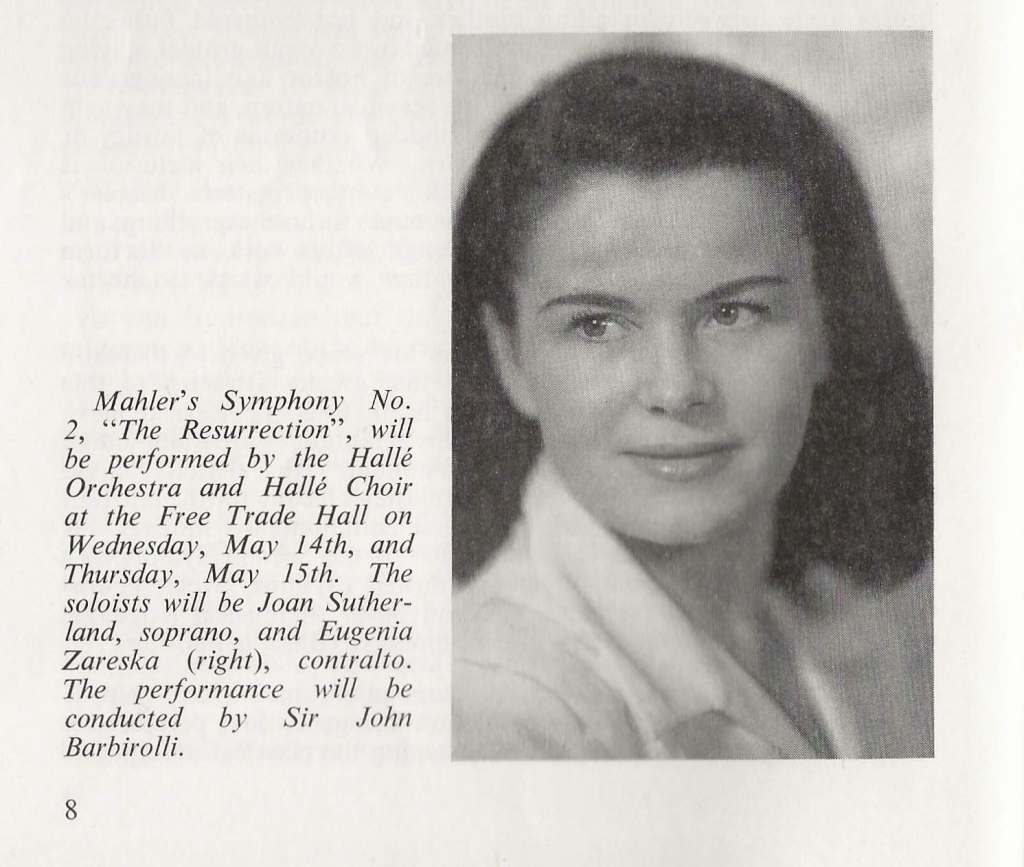

For the two performances the Hallé Choir were trained by Eric Chadwick and two soloists were engaged. I do not normally say a great deal about soloists within this blog but in this instance it is worth saying a little. The mezzo-soprano, who would sing the magnificent Urlicht movement, was the Ukrainian born Eugenia Zareska who had become renowned as a outstanding interpreter of Mahler following a performance of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with the LSO in 1946. More significantly, Barbirolli engaged none other than Joan Sutherland to sing the soprano solo in the final movement.

Born in Australia in 1926 and so still only in her early 30s, Sutherland had spent the previous few years as part of the Covent Garden company trying to forge a career as a Wagnerian soprano, but her husband Richard Bonynge was instrumental in her move in the late 1950s more towards the coloratura bel canto roles. Her big break, and one which defined her later career, was her appearance in 1959 as the titular heroine in Franco Zeffirelli’s acclaimed production of Donizetti’s Lucia de Lammermoor at the Royal Opera House. A star was born at that moment, but that moment was not May 1958 and it is remarkable that in neither of the two reviews I will quote from below is she referred to by name – surely that would not have been the case had the concert been two years later! Anyway, in May 1958 Sutherland had other worries. According to her autobiography, during her busy schedule at the beginning of 1958 she had developed ‘two very swollen and painful knees’ that ‘were like two pumpkins’ and were bad enough by April for her to be forced to go into hospital. She takes up the story:

I decided to leave the hospital – against their advice – and signed a waiver of any responsibility on their part should I become worse or permanently disabled. Anyway, I had to get myself in shape to sing with the Hallé Orchestra and dear Sir John Barbirolli on May 14 and 15 – and it was already the sixth. Fortunately nothing too disastrous happened and the knees gradually went back to almost normal, although they have always had a tendency to swell after long hours of standing for staging rehearsals… However, I did my concert with the Hallé.

from ‘A Prima Donna’s Progress – The Autobiography of Joan Sutherland‘

The concerts were trailed extensively in the May 1958 edition of the Hallé’s magazine Hallé News. In an article entitled ‘Progress‘ Stephen Bagnall exhibits signs of the general distrust around Mahler’s name that I alluded to earlier, but also gives testament to how Barbirolli’s proselytising efforts on his behalf were beginning to pay dividends. Despite the fact that ‘five or six years ago the name Mahler on a programme would have been enough to make me cross that particular concert of the list’, he declares he is looking forward to hearing the 2nd Symphony. Similarly, in an introduction to the symphony for readers, Leonard Duck refers back to Barbirolli’s performance of the 9th Symphony four years earlier and quotes ‘an eminent critic’, presumably Neville Cardus, who when describing the work ‘took the line, broadly, that the music might be banal, sentimental, neurotic and long-winded, but was well worth listening to for its beauty and intensity of feeling,’ thus reflecting both the old and the newer attitudes to Mahler’s music. Duck felt this to be good psychology ‘for, being prepared for the worst, the audience found the experience more pleasing than they had feared, and were able to face a repeat performance early in the following season with equanimity’.

Importantly, Duck gave his readers a programme for the symphony (based on one originally provided by Mahler), that would help them understand what was remarkably, for most of them at least, completely new music:

The first movement asks if humanity has any continuing existence, or is life an empty dream? The second movement recalls blissful moments of lost youth and innocence, the third is possessed by the spirit of unbelief and negation, while the fourth seeks the consolations of simple faith. Finally, the Last Judgment arrives, the graves burst open and the dead march past in endless procession. A chorus of heavenly Beings sing “Arise! Resurrection is granted to you” and the glory of God appears. And behold! there is no judgment -no sinners, no righteous- only overwhelming love, blissful knowledge and being.

From ‘Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony’ by Leonard Duck in Hallé News – May 1958

However, come the first concert, and Colin Mason’s often vitriolic review in the Manchester Guardian obviously held no truck with Bagnall and Duck’s encouraging words about Mahler’s music. It is a classic example of a reviewer reviewing the work rather than the performance of that work. Therefore, it was not the quality of the playing and singing he disliked, but the quality of the music, particularly the music of the two outer movements. His final paragraph is the epitome of damning with faint praise (and contains the only mention of the Hallé Choir):

The charm of the second movement, and intermittently of the third and fourth, which occupy only the middle half-hour of the hour-and-a-half, does not weigh much against all this – or against the cost of putting these two performances on… This is no criticism of Sir John Barbirolli or the Hallé Orchestra and Choir, who after a slightly tentative first movement gave a splendid performance, and deserve our gratitude for letting us hear a work so rarely played – even though all we have learned is that it deserves no better.

From review of 14th May concert by Colin Mason in the Manchester Guardian – May 15th, 1958

Peter Heyworth, writing in The Observer the following Sunday, gives a much kinder assessment of the concert, though even he cannot resist a few digs. To him, compared to works of other late Romantic composers such as Brahms and Schoenberg, this ‘relatively immature’ symphony sounds ‘inflated, rhetorical and bombastic’. However, he believes these perceived shortcomings ‘fade into relative unimportance before the ardour and conviction, the inventiveness and the imaginative sweep that pervades much of the music…’ He praises the performance despite what he sees as a lack of ‘neurotic anguish’, which he considers ‘an essential constituent of the idiom’, which to 21st century listeners may seem fair comment. He writes that ‘[Barbirolli] gets its passion and its extremities of mood, and he realises the fascinating orchestral texture most convincingly’, and that ‘the Hallé Choir and Orchestra (and notably the distinguished first flute) responded nobly to his demands.’ Again no mention was made of either soloist, or indeed that there even were solos!

The audience reaction was, however, overwhelmingly positive, such that the ‘Passing Notes’ section of the March 1959 edition of Hallé News talks of Barbirolli returning from a trip to America to conduct further performances of the Resurrection Symphony on March 11th and 12th and that ‘it will be recalled that Sir John included this Symphony in the present Season following the tremendous reception it received after the final mid-week concerts in the Centenary Year.’ In addition to to these two concerts the choir and orchestra also gave a performance of the symphony in Leeds Town Hall on March 14th. The Free Trade Hall concert on March 12th was broadcast by the BBC, with a recording of the broadcast eventually finding its way in 2014 onto a Barbirolli Society CD that I talked about in this blog. I referred there to Colin Mason’s review of the concert, which showed he had lost none of his antipathy towards the symphony. I will repeat the section of the review I referenced in that previous blog to show that at least now the soloists were mentioned, though now as you will see Joan Sutherland had moved on to bigger and better things:

In ninety minutes listening we have heard perhaps as much musical substance as Mozart or Schubert compresses into nine. The rest is padding, sound and fury, by which we let ourselves be hypnotised… The contralto song was very beautifully sung by Eugenia Zareska, and the small parts for solo soprano and chorus in the fifth movement by Victoria Elliott and the Hallé Choir.

From review of 11th March concert by Colin Mason in the Manchester Guardian – March 12th, 1958

Having waited 63 years for its performance by the Hallé Choir, the symphony received five performance inside the space of a year, and it has been regularly performed by the choir ever since. Two notable performances were one in 2003 conducted by the New York businessman Gilbert Kaplan, who had a second career as an amateur conductor and who only ever conducted Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony, and one conducted by Markus Stenz in 2010 that formed part of the Hallé and BBC Philharmonic’s joint celebration of the 150th anniversary of Mahler’s birth.

And so to January 2025, when the massed ranks of the Hallé Choir, the Hallé Youth Choir, and soloists Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha and Dame Sarah Connolly joined a super-sized Hallé Orchestra for the latest performance of the symphony under Kahchun Wong. It certainly feels at the time of writing, a couple of weeks after the event, that this performance will be considered one for the ages. A spontaneous standing ovation was followed by a series of reviews heralding the concert as a landmark statement by the orchestra’s new conductor. Sarah Noble, writing in the Guardian, was particularly praising of the vocal contributions:

With the arrival of voices in the fourth and fifth movements came a concession to pure lyricism: Sarah Connolly’s Urlicht was a moment of radiant stillness, and amid the sound and fury of the final scherzo, the immaculate first vocal entrance of the choir – singing while still seated, and without scores – seemed to shimmer out of the ether, before mingling to celestial effect with Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha’s opalescent soprano.

From review of 16th January concert by Sarah Noble in the Guardian – January 17th, 2025

Rebecca Franks, writing in the Times, talks of ‘truly fine singing by the Hallé Choir and Hallé Youth Choir ‘ and of how ‘the finale’s message of rebirth rang forth, gilded by the soloists Sarah Connolly and Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha, as well as three mighty church bells.’

However, I want the last word on this performance to come from an audience member rather than a professional critic. Attending the concert on January 16th was Keith Smith, the cousin of a member of the Hallé Choir bass section, David Burgess. Remarkably, Keith had been present at one of those first two performances of the symphony back in 1958. In a letter to David after the concert he remembered the excellence of Joan Sutherland, of the off-stage brass in the final movement, and of course of Barbirolli’s choir. His final verdict on the concert, however, demonstrates how far the orchestra and choir have come in the last 68 years when measured against this mighty symphony:

Of course the choir, good as it was, was not in the same class as today’s choir: that’s fact, unquestionably. Frankly, it is difficult to imagine an orchestra and choir, worldwide, better.

Keith Smith

References

Stephen Bagnall, ‘Progress’, Hallé News (May 1958)

Lawrence F Bernstein, Inside Mahler’s Second Symphony- A Listener’s Guide. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022)

Geoffrey S Cahn, ‘Mahler, Gustav (1860-1911)’ in Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism. (Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, 2018)

Leonard Duck, ‘Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony’, Hallé News (May 1958)

Jens Malte Fischer. Gustav Mahler. Translated by Stewart Spencer. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011)

Raymond Holden, ‘Sutherland, Dame Joan Alston’ in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014)

Michael Kennedy, Barbirolli Conductor Laureate – The Authorised Biography. (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1971)

Thomas Peattie, Gustav Mahler’s Symphonic Landscapes. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Charles Reid, John Barbirolli – A Biography. (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1971)

Joan Sutherland, A Prima Donna’s Progress – The Autobiography of Joan Sutherland. (London: Orion, 1997)

Ralph Vaughan Williams, ‘A Musical Autobiography’ in Michael Kennedy (ed.), National Music and Other Essays. (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1986, 2nd edn.)

https://www.mahlersociety.org/gustav-mahler

Manchester Guardian and Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Times Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Hallé Archives

Leave a comment