Preamble

It’s been a very long time since my last blog. This has been through necessity rather than choice as I’ve been recovering from a serious knee injury. I’m hoping a return to fitness will see normal service being resumed! So firstly, apologies for being absent.

During the 2024/25 Hallé season, the first with Kahchun Wong as the new Principal Conductor, the Hallé Choir will be performing works by two women composers, Lili Boulanger and Kaija Saariaho. In addition one of these will be conducted by a woman conductor, Delyana Lazarova, formerly assistant conductor to Sir Mark Elder. Some choir members will also be singing some of Rachel Portman’s music for the animation Mimi and the Mountain Dragon, conducted by Olivia Clarke. In the 21st century, this state of events might not seem unusual in and of itself, but when one looks at the history of the choir going back to 1858 it is very much unusual.

How so? Having talked in a previous blog about the choir’s radio broadcast of Dame Ethel Smyth’s The Prison in 1934 I thought I would look through the choir’s history and see how many times in concert the choir has either performed works by women or been conducted by women. As I’m sure would be the case if I investigated the archives of most of the major symphony orchestras in this country, such concerts have been pitifully few. Arguably the situation is improving. A couple of seasons ago coming out of the pandemic the Hallé made a conscious decision to engage an equal number of male and female conductors during the season and though that 50:50 ratio hasn’t been maintained, each season now includes a significant number of women conductors. Radio 3 now regularly plays music by the likes of Hildegard of Bingen, Louise Farrenc, Fanny Mendelssohn, Clara Wieck, Amy Beach and Florence Price to name but a few. A few years ago at a chamber concert in Santa Barbara I was exposed for the first time to the music of Rebecca Clarke, specifically her viola sonata, and was blown away by how fresh and distinctive it sounded – why had I never heard of this composer?! Leah Broad’s excellent recent book Quartet gave me much biographical detail on this exceptional composer and three other remarkable female British composers of the 20th century, one of whom was Ethel Smyth.

And yet… looking at the Hallé’s wonderful new online concert archive, which currently lists all performances from 1858 up to around 1990, of the nearly 300 conductors engaged during that period, only four were women – Sian Edwards, Iona Brown, Nadia Boulanger and Ethel Smyth, and only one of these, Nadia Boulanger, conducted the choir. Of the over 900 composers whose works were performed during that period only 26 were women, and a large number of those were composers of the type of Victorian parlour ballads used by Charles Hallé to fill up his early vocal concerts. Of the 26 only 2 had performances of choral pieces sung by the Hallé Choir, namely the aforementioned Ethel Smyth and Lili Boulanger, of whom much more shortly.

Some more facts, referenced in an academic essay from last year entitled ‘Where are the Female Composers?’. Classic FM’s 2023 list of the top 30 composers only included two women, and in the same year BBC Music magazine’s list of the top 50 composers still only included two women. The essay includes a quote by John Stuart Mill that, whilst it has more than a whiff of misogyny about it, makes a valid point that the problem for the budding woman composer was, at least in the 19th century, not ability but opportunity:

Women are taught music, but not for the purpose of composing, only for executing it: and accordingly, it is only as composers, that men… are superior to women… But even this natural gift [for composition], to be made available for great creations, requires study, and professional devotion to the pursuit…. [T]he men who are acquainted with the principles of musical composition must be counted by hundreds, or more probably by thousands, the women barely by scores: so that here again, on the doctrine of averages, we cannot reasonably expect to see more than one eminent women to fifty eminent men.

John Stuart Mill (1869)

There were indeed few opportunities for women to learn composition at music colleges until the end of the 19th century and into the next, with a musical family environment being the most common starting point for budding women composers of the time. Even here though their creative endeavours would often be indulged rather than encouraged. Fanny Mendelssohn’s father, comparing her to her brother Felix, wrote the following in a letter: ‘Music will perhaps become his [i.e. Felix’s] profession, while for you it can and must be only an ornament.’ Felix himself was equally condescending in a letter written to their mother Lea:

From my knowledge of Fanny I should say that she has neither inclination nor vocation for authorship. She is too much all that a woman ought to be for this. She regulates her house, and neither thinks of the public nor of the musical world, nor even of music at all, until her first duties are fulfilled. Publishing would only disturb her in these, and I cannot say that I approve of it.

Letter from Felix Mendelssohn to Lea Mendelssohn

Clara Wieck was taught composition by her father and for nearly 20 years from the age of 11 produced a number of compositions a year, including piano pieces, lieder and a remarkable Piano Concerto written when she was only 14 that do not suffer at all in comparison to the works of her future husband Robert Schumann. However, the demands of motherhood following her marriage to Schumann, her ongoing concert career (she was a virtuoso pianist – women were allowed to be soloists), and a reticence to believe in her own right to be a composer led her to effectively stop composing before she turned 30. I find this quote from her agonisingly sad:

I once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose – there has never yet been one able to do it. Should I expect to be the one? To believe that would be arrogant.

Clara Wieck Schumann

And of course, for the likes of Clara and Fanny and others like, writing works was one thing – getting them performed was quite another thing. Within this blog I will look how, in the first 150 years of the Hallé Choir’s existence and the dearth of representation for women composers and conductors both in the orchestra’s and the choir’s performances, three women stand out, the formidable Ethel Smyth, and the sisters Nadia and Lili Boulanger.

Ethel Smyth

Ethel Smyth was not going to be stopped from pursuing her dream of being a composer by any self-doubt or Victorian conventions. As Leah Broad writes: ‘Her life is completely unrepresentative of the experience of most women composers in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries.’ Born in 1858 she was a gifted musician from an early age and when she decided she wanted to enrol at the Leipzig Conservatory, no-one, not even her father who battled with her long and hard over the subject, was going to stop her. While there she studied under Carl Reinecke and made acquaintances with both Johannes Brahms, whose late romantic style she very much absorbed, and, interestingly, Clara Schumann.

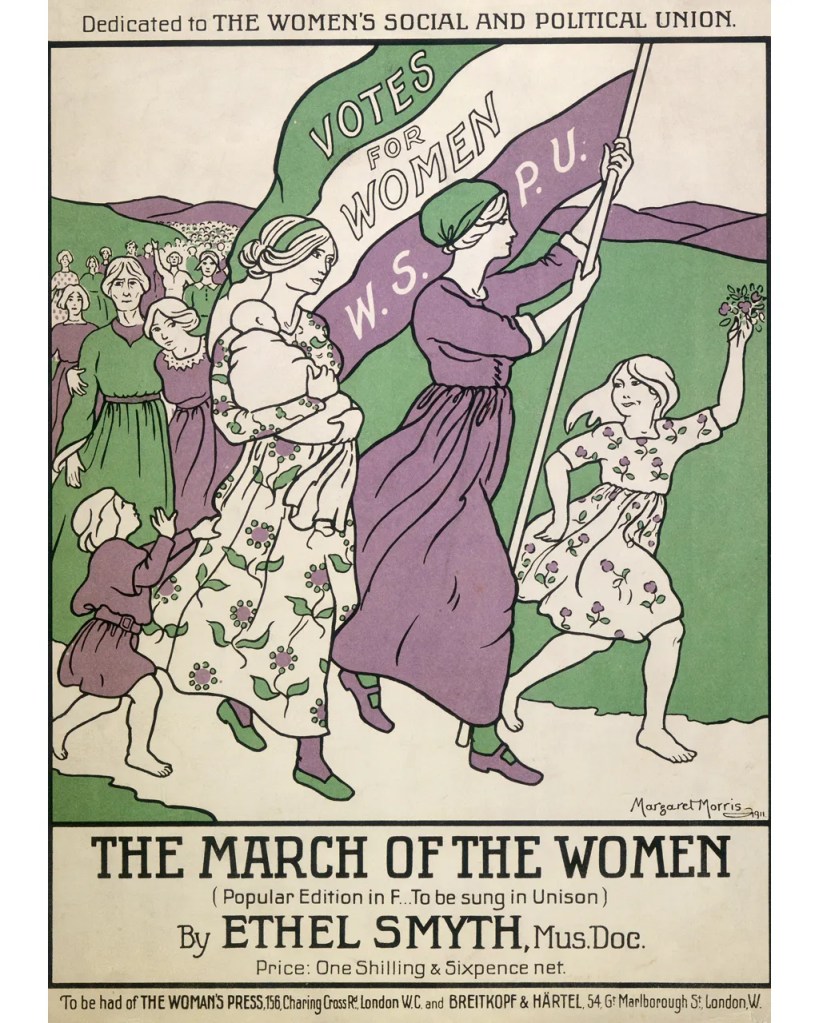

On returning to England, through sheer effort of will (she was very persuasive!) and the quality of her work, she managed to get her compositions played both here and in Europe, often with herself conducting. For a while she was one of the most popular composers of her time. She was perhaps most famous in her lifetime for writing the anthem of the women’s suffrage movement, The March of the Women. Following the receipt of a Damehood in 1920 she wrote a letter to the Daily Mail which incited a campaign to get more of her works played – she was that sort of a fighter. However, as an essentially conservative Late Romantic composer in the tradition of Brahms of Wagner (and, it has to be said, because she was a woman), her music began to fall out of favour as music developed in more radical directions, especially following her death in 1944. Until a recent renaissance her music was known more by reputation than performance.

I described in that previous blog how a performance in 1934 of her cantata The Prison, a requiem for her lifelong friend Henry Brewster, was broadcast by the BBC. However, that wasn’t the Hallé Choir’s first encounter with the work of this remarkable woman. Thomas Beecham was a longtime champion of the works of Ethel Smyth and in November 1915, despite what must have been a significantly depleted choir given the ongoing war, was involved in a Hallé concert in the Free Trade Hall that was billed as ‘A Great Choral Evening’. Whilst both parts of the programme began with the choir’s longtime Choral Director R.H. Wilson conducting, first in one of Handel’s Coronation Anthems and then in Bach’s motet Komm, Jesu, Komm, the rest of a richly varied bill of fare was conducted by Beecham. It included the Stabat Mater from Verdi’s Four Sacred Pieces, and Debussy’s The Blessed Damozel which, with its original French words and French title of La Damoiselle Élue, was performed by the choir at the BBC Proms in 2018 and later released on CD. Hidden in the middle of the second half, however, were a couple of short choral songs by Ethel Smyth described by the Manchester Guardian reviewer Samuel Langford as her ‘new pieces’.

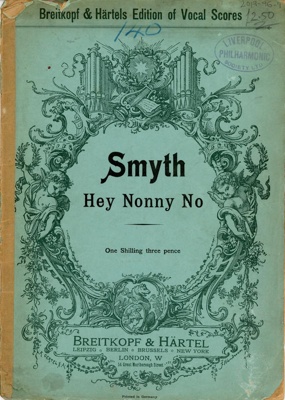

Sleepless Dreams, set to words by Dante Gabriel Rosetti, and Hey Nonny No, set to an anonymous 16th source, were indeed relatively new, having been completed in 1910. They were the result of one of what Ethel called her ‘passions’, on this occasion for the harpsichordist Violet Gordon-Woodhouse. Leah Broad points out the sexual undercurrents within both pieces, with in Sleepless Dreams the poem’s speaker tossing and turning at night ‘lonely and unable to sleep, tormented by erotic visions that appear whenever they close their eyes,’ and with the title Hey Nonny No being ‘a nonsense phrase that was often used in the Elizabethan era to suggest a sexual subtext, alluding to acts that could not be explicitly spoken.’ During the writing of the works Ethel actually gave Violet a copy of Sappho’s poems dedicating it ‘To Violet from Ethel – “Hey Nonny No” epoch November 1909 – “I love delicacy, and for me love has the sun’s splendour and beauty”.’

There are no official recordings currently available of either of these pieces, though a live YouTube recording of Sleepless Dreams does give hints of the passion that lay behind its composition, a passion of which I’m sure neither choir, audience or Thomas Beecham would have been aware! Neither I am sure was Samuel Langford, though he was impressed with both pieces and reflected the general high regard in which Smyth’s work was held at that time:

…the choral dance “Hey Nonny No”… was both sung and played with equal zest, and was very well received. There are finer things in the closing section of her setting of Rossetti’s “Sleepless Dreams,” which quite shows her to be in the front rank among the most solemn harmonists of our day.

Samuel Langford writing in the Manchester Guardian, November 5th 1915

In a roundup of 1915 concerts in his centenary history of the Hallé Orchestra, Michael Kennedy mentions every piece in the concert except the two Smyth pieces, and they were never reprised by the choir. Kennedy did however mention that six days later on November 11th (a date that three years later would take on extra significance), in another mixed concert of music that included the great Adolph Brodsky playing the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto, Ethel Smyth herself conducted the overture to her new opera The Boatswain’s Mate. In so doing Smyth became the first woman to conduct the Hallé, though it’s perhaps a reflection of attitudes when Kennedy was writing his history in 1958 that he did not seem to think it relevant to mention the fact.

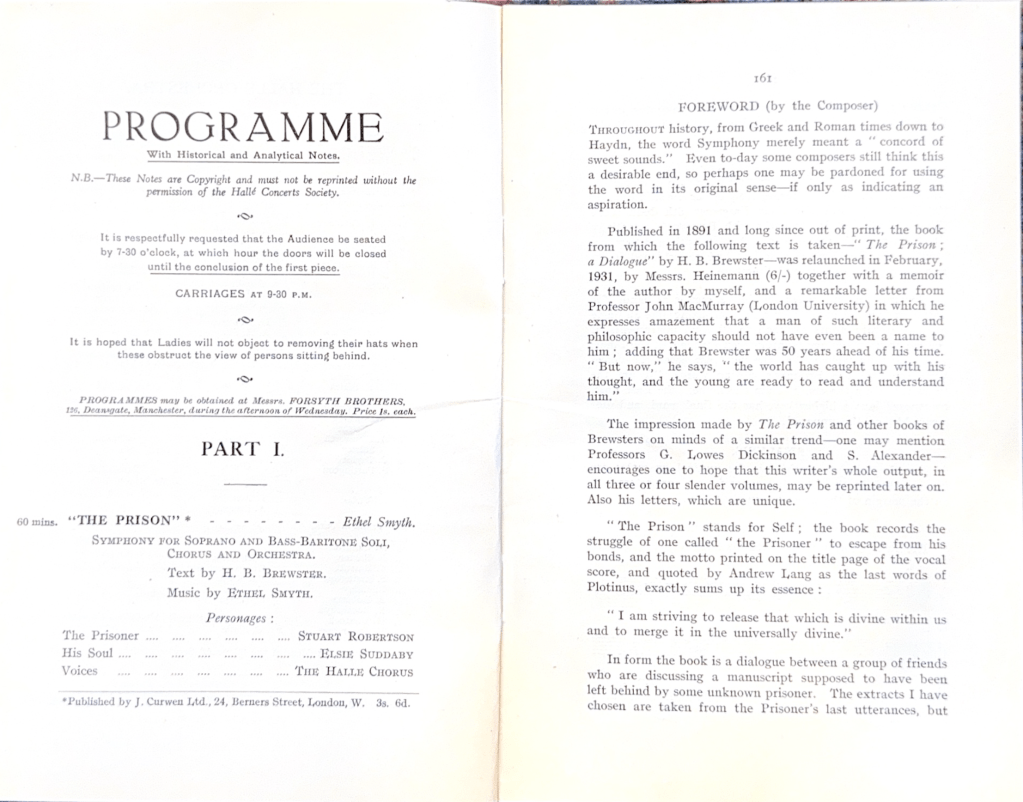

I described the performance of The Prison in some detail in the previous blog, but since writing it I have managed to have a look at the programme for the concert and as an aside wanted to point out an interesting feature of the programmes of this period. You will notice below that the programme includes a foreword by the composer about the work. This continues over the next four or five pages with a detailed musical analysis of the work, including extracts from the musical score, that require a relatively detailed musical knowledge on the part of the concert-going reader. No programme writer would think of providing such detailed information today!

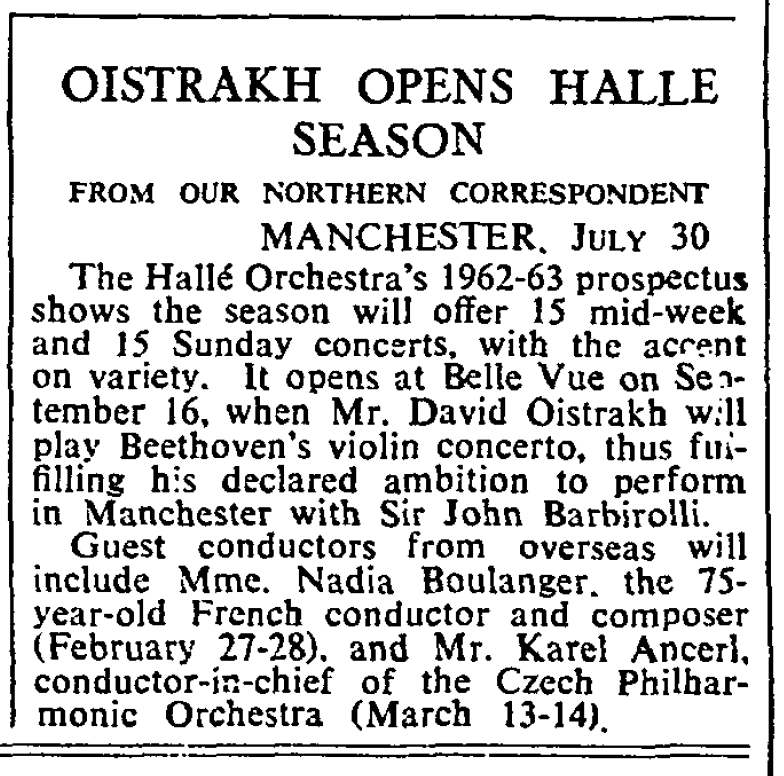

I mentioned above how Ethel was the first woman to conduct the orchestra. It would be nearly 50 years, a scarcely thinkable time period now, before a woman would again conduct the orchestra, namely Nadia Boulanger, though memories were so short that pre-publicity for the concert in The Times suggested she was the first woman to conduct the orchestra. One of the works she conducted was by her sister Lili, whose short life, as I will explain, was tragic and inspiring in equal measure.

Lili and Nadia Boulanger

The ‘Northern Correspondent’ of The Times wrote a short piece in the newspaper on July 30th, 1962 outlining the highlights of the forthcoming 1962/3 season, a season that, though they did not know it yet would be affected by the ‘Big Freeze’, in which there was scarcely a day without frost from the end of December 1962 to the beginning of March 1963. One of these highlights was set to take place at the end of February when, in the event, blizzards were still sweeping the country. It was the visit of Nadia Boulanger, described as ‘the 75 year-old French conductor and composer’, to conduct the orchestra and choir over two nights.

This would be quite the event. Not only would Nadia Boulanger be the first woman to conduct a complete Hallé concert, but she was recognised worldwide as a major figure important not just for the composing and conducting that the article references, but for her teaching. Simply as a composition teacher, her particular speciality, she gave lessons to some of the most important musical figures of the 20th century. Within the classical field we see names such as the American composers Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland and Philip Glass, and British composers Lennox Berkeley, Richard Rodney Bennet and Thea Musgrave (one of those 26 female composers whose music the Hallé played between 1858 and 1990). Within her native France she taught Olivier Messiaen, Jean Francaix and Michel Legrand. Mention of Michel Legrand also brings to mind the composers and arrangers in field of jazz and popular music that she taught, people such as Astor Piazolla, Robert Russell Bennett, Burt Bacharach, Donald Byrd and Quincy Jones. Given Quincy Jones was his producer and arranger for many years one can therefore confidently state that there are only three degrees of separation between the Hallé Choir and Michael Jackson!

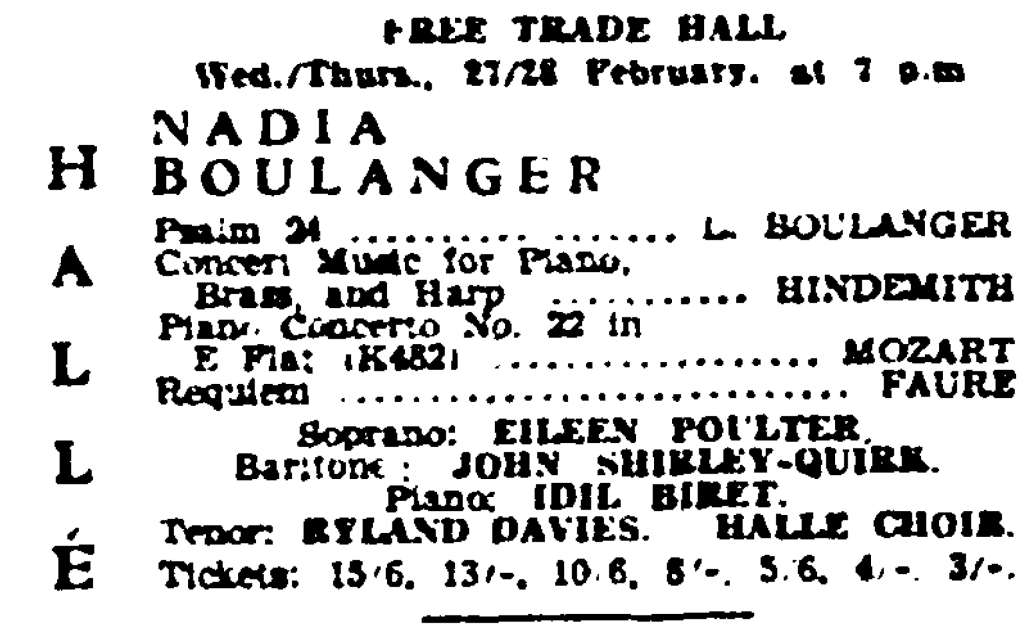

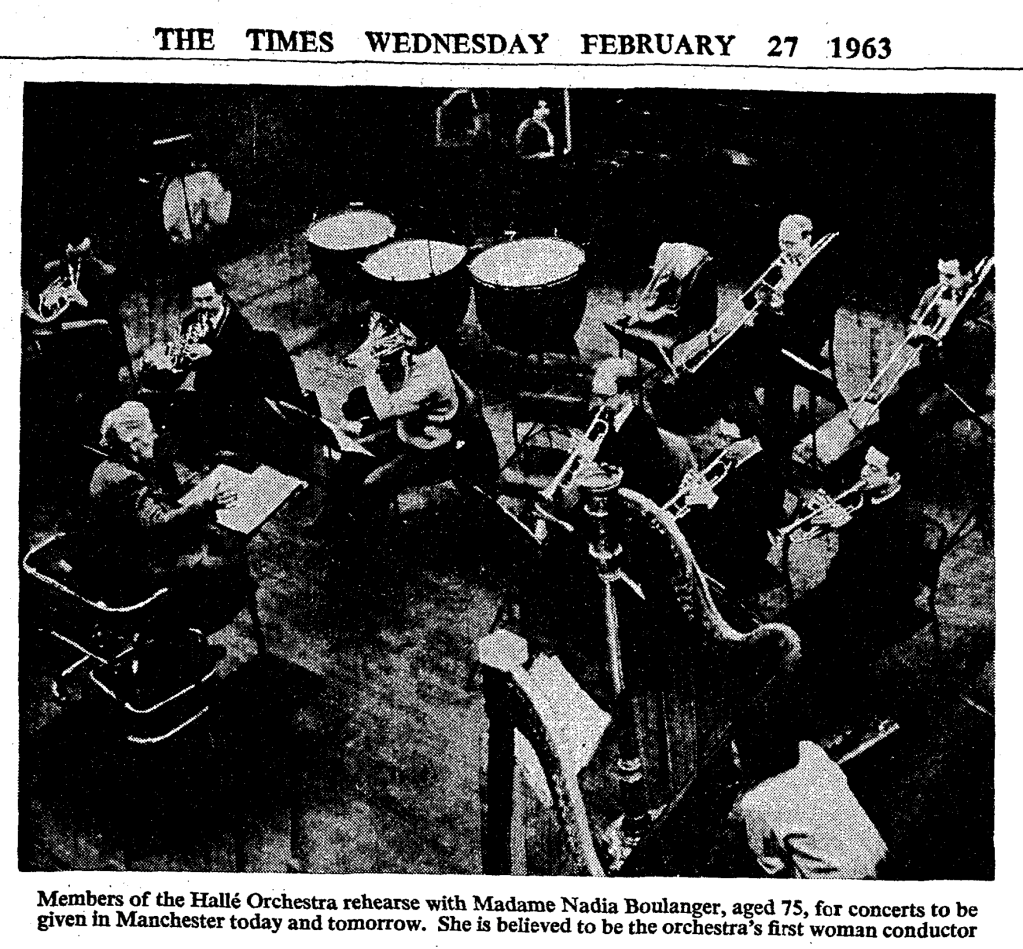

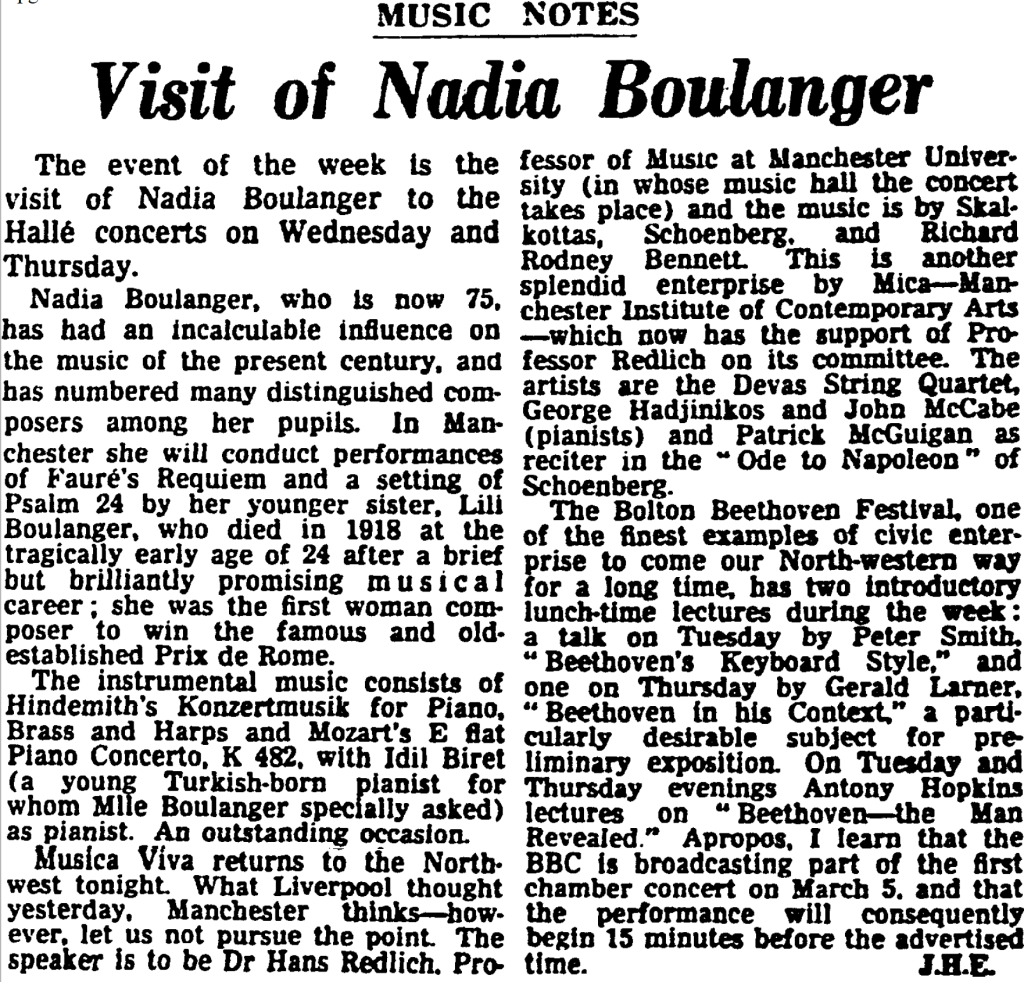

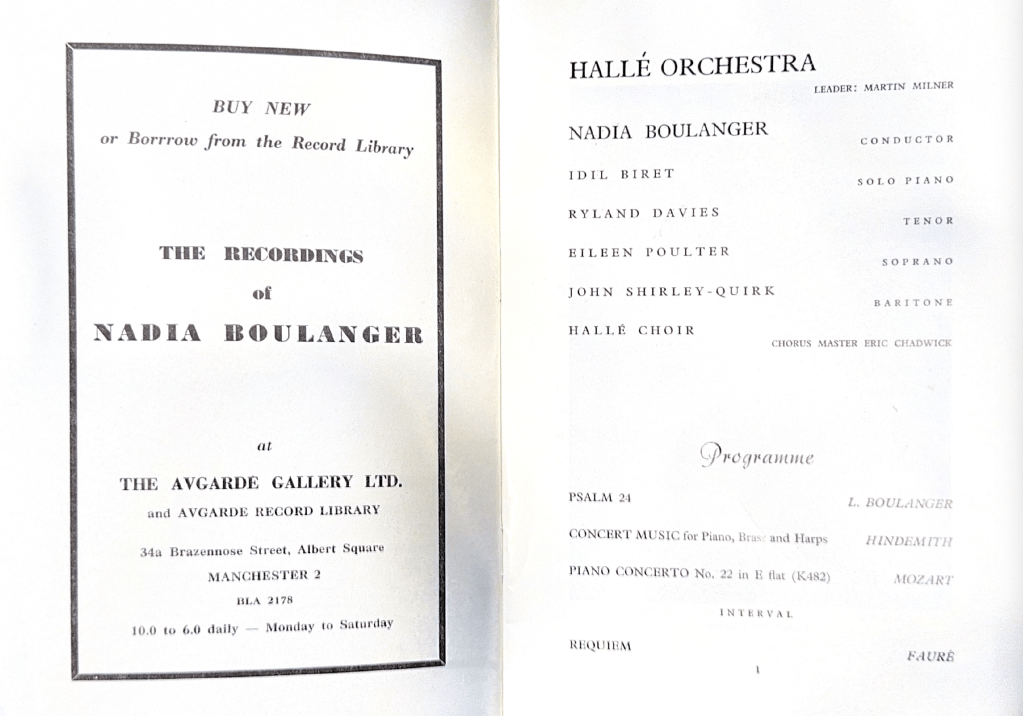

The concerts, with the same programme being performed on both 27th and 28th February, were well trailed. As well as the standard advertisements in the Manchester Guardian, the paper’s music critic J.H. Elliot headlined his Music Notes column on 25th February with Nadia’s visit, describing how she ‘has had an incalculable influence on the music of the present century, and has numbered many distinguished composers among her pupils.’ On the morning of the first concert The Times featured a photograph of Nadia rehearsing the orchestra with the misleading comment that ‘she is believed to be the orchestra’s first woman conductor.’

The programme chosen for the two concerts was varied. There were two works for piano and orchestra by Mozart and Hindemith that would be played by the 21 year old Turkish pianist Idil Biret, with the choir singing in a performance of a particular favourite of Nadia’s that she recorded more than once, Fauré’s Requiem, with Eileen Poulter and John Shirley Quirk as the soloists. In the context of this blog, however, the most intriguing work in the programme was the one that began the concert, a setting in French of Psalm 24 by Nadia Boulanger’s younger sister Lili, whose music she championed throughout her conducting career.

Like Fanny Mendelssohn and Clara Wieck before them, Nadia and Lili Boulanger were born into an intensely musical family. Their father Ernest Boulanger was born in 1815 (remarkably he was 72 when Nadia was born and 77 when Lili was born!). He studied at the Paris Conservatoire and won the Prix de Rome composition prize. He continued his composing career, specialising particularly in choral music, and in 1877, at the age of married Raissa Mychetskaya, one of his vocal students at the Paris Conservatoire and 41 years his junior.

Maria-Juliette Olga Boulanger, known affectionately thereafter as ‘Lili’ was born in 1893, and both she and her sister Nadia were encouraged in their musical studies by their parents. Nadia entered the Paris Conservatoire at the age of 9, studying with Gabriel Fauré, and Lili would join her older sister there as a young girl, sitting, listening and absorbing. At the age of two she contracted bronchial pneumonia, an event that would mark her for the rest of life given the effect it had on her immune system. From that moment on there almost seemed to be a tacet acceptance within the family that Lili was living on borrowed time and that whatever mark she was going to make on the world, she would have to make quickly.

Because of her frail health she wasn’t able to enter formal musical studies until she was 16, which must have increased the sense of urgency when she at last entered the Conservatoire in 1909. She studied harmony and composition with Georges Caussade and Paul Vidal. However, also keeping a watchful eye on her was her devoted sister Nadia and LIli became in many respects her first pupil of many. Progress was so fast that in 1912 she decided to enter the Prix de Rome, the competition her father had won so many years before and which her sister had entered on a number of occasions over the previous few years. A recurrence of her illness meant she had to withdraw before the final, but the following year she competed again and won, with Faust et Helène, written to a set text based, like Mahler’s 8th Symphony of a few years earlier, on Goethe’s Faust. Whilst she wasn’t the youngest winner of the prize (Émile Paladilhe had won in 1860 at the age of 9!), she was the first woman to win.

Along with the prize came a publishing contract with Ricordi, and over the following 5 years, knowing she was racing against time, and always with her sister there to help if needed, she produced a number of astonishing works that hint at what she might have achieved had she lived. She finally lost her fight in March 1918, when she finally succumbed to the intestinal tuberculosis that her weakened immune system had let in.

As to her music, whilst obviously influenced by the composers that had come before her, particularly Fauré, Debussy and Wagner, there are dark undercurrents there that are very much her own, perhaps influenced by her own bodily frailty and the condition of the world at the time (most of her works were composed during the First World War). Standing out amongst her compositions are three psalm settings in French that she composed during 1916 and 1917, settings of Psalm 129, Psalm 130 (which the Hallé Choir will be performing in November 2024) and Psalm 24 (‘The earth is the Lord’s, and the fulness thereof’), the setting chosen to open Nadia’s concerts in Manchester. Set for the unusual forces of choir, tenor soloist (sung in the Free Trade Hall by Ryland Davies), brass, harps, timpani and organ, and barely four minutes long, the work eschewed the darker overtones of, particularly, the Psalm 130 setting, to provide a thrilling fanfare-like introduction to the concert with loud brass interjections and strident singing first from the tenors and basses and then the whole choir.

J.H. Elliot, reviewing the first of the concerts in the Guardian, picked up the energy of the piece, and also the tragedy of Lili’s short life. He is almost mourning the composer rather than reviewing the performance:

The concert began with the short setting of Psalm 24 by Lili Boulanger, the younger sister of Nadia Boulanger. Her early death was a blow to French music. The work has an Old Testament fervour, almost a ferocity, that is far beyond the prevailing temper of Gallic music of its time. The loss here was incalculable.

J.H. Elliot writing in the Manchester Guardian, February 28th, 1963

I cannot leave discussion of these two concerts without mentioning that alongside the reviewer J.H. Elliot there was another person present with almost the same name as him. If you look at the list of Tenors in the programme you will see a young man by the name of John A. Elliott. Though he spent time out of the choir after these concerts helping raise his young family, he rejoined the choir and is still singing with the choir today over 60 years later and will be singing Lili’s Psalm 130 setting with the tenors in November. This blog probably would not have happened without John, as I was unaware of the 1963 concerts until he approached me in the interval of our first rehearsal of Psalm 130 and told me about the time he had sung under Nadia Boulanger. Sadly, his abiding memory of the concerts is not the Lili Boulanger piece but singing the Fauré Requiem with John Shirley Quirk, but I am extremely grateful to John for making me aware of this remarkable piece of the choir’s history.

Postlude

The two concerts singing Ethel Smyth’s music and the two concerts with Nadia Boulanger singing Lili Boulanger’s music were the sum total of the choir’s experience with female composers and conductors up to 1990, and it is only really in the last 20 years that the situation has begun to improve. In the 2000s Frances Cooke became Associate Director of the Hallé Choir alongside James Burton and spent a period as Hallé Choir Director in the early 2010s, shortly after Madeleine Venner had been appointed as the first woman to be Hallé Choral Director. The choir has slowly begun to perform more works by women composers. At the 2013 Hallé Christmas Carol concerts Frances Cooke conducted the choir in performances of Cecilia McDowall’s atmostpheric Anunciation, set to a text by John Donne, and thus became the second woman to conduct the Hallé Choir in concert (unless there are concerts in the period 1990 to 2009 that I don’t yet know about). She also conducted members of the choir in memorial concerts in Belgium at around this time. Madeleine Venner became the third woman to conduct the choir, but it was not until December 2021, with the choir’s first full performance of Handel’s Messiah that the very excellent Sofi Jeannin, principal conductor of the BBC Singers, became the fourth woman to conduct the choir. With regard to female composers, in addition to the McDowall performances there have been two events that I have already covered on this blog, the performance in 2019 of Emily Howard’s The Anvil, written to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre, and the recording of Rachel Portman’s soundtrack to Mimi and the Mountain Dragon.

As I wrote at the beginning of this blog, the 2024/25 season will see the choir perform Lili Boulanger’s setting of Psalm 130, conducted by Delyana Lazarova, and the late Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho’s Oltra Mar, conducted by the Hallé’s current Artist-in-Residence, Thomas Adès. It will also see members of the choir and the Hallé Youth Training Choir perform some of Rachel Portman’s soundtrack for Mimi and the Mountain Dragon live alongside a live screening of the animation, conducted by the young British/Irish conductor Olivia Clarke. One would hope that this is a sign of things to come. There are many exciting choral works by contemporary women composers that I have performed in other choirs and heard in concert, composers such as Sally Beamish, Dobrinka Tabakova, Errolyn Wallen and Grace-Evangeline Mason, works that are out there waiting to be performed by the Hallé Choir. It has been too long already but I hope it will not be too long before a concert of a work by a woman composer conducted by a woman conductor stops being worthy of note and simply becomes just another concert.

The Hallé Choir will be performing Psalm 130 by Lili Boulanger on November 14th, 2024, conducted by Delyana Lazarova.

Members of the Hallé Choir and the Hallé Youth Training Choir will be performing Mimi and the Mountain Dragon by Rachel Portman on December 21st and 22nd, 2024, conducted by Olivia Clarke.

The Hallé Choir will be performing Oltra Mar by Kaija Saariaho on March 27th, 2025, conducted by Thomas Adès.

References

Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy (ed.), Letters of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy from 1833 to 1847. Translated by Lady Wallace. (London: Longman, 1864)

Karol J. Borowiecki, Martin Kristensen, Martin Hørlyk Marc T. Law, “Where are the Female Composers? Human Capital and Gender Inequality in Music”, History (July 10, 2024).

Leah Broad, Quartet: How Four Women Changed The Musical World (London: Faber & Faber, 2023)

Sebastian Hensel (ed.), The Mendelssohn Family (1729–1847) From Letters and Journals. Translated by Carl Klingemann. (London: Sampson Low and Co., 1884)

Matthew Scott Johnson, “The Recognition of Female Composers,” Agora: Vol. 2005, Article 9 (2005).

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition – A Century of Music, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Times Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Hallé Archives

Leave a comment