Introduction

The plan for my first blog of 2024 was to move from the choir’s appearances on record to describing the choir’s history of radio and television broadcasts. That will come in the next two blogs, but as we entered 2024 I was conscious that later in the year we will be marking the fifth anniversary of the first mention in the news, far away in China, of a troubling sounding new virus, the novel coronavirus that would become known to us all as Covid-19. This set me thinking. Firstly I was interested in how the choir’s experience of the Covid pandemic contrasted with that of the pandemic that swept the globe just over 100 years previously, namely the so-called ‘Spanish Flu’. Secondly I was aware that just as the Spanish Flu soon vanished from the public consciousness through the 1920s and 1930s, so it was vital that I record, in however small a fashion, the story of the Hallé Choir’s journey through the Covid pandemic.

1918-1919 – The Spanish Flu

So to begin at the beginning, 1918 saw the aftermath of one of the Hallé Orchestra’s periodic financial crises, which had caused the numbers of concerts given to the people of Manchester in the 1917/18 season reduced to 16 and the season shortened. The result was that the Hallé Choir’s last concert of that season was not in June or July as might normally be the case, but in early March. As conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham, the choir’s performance of Mendelssohn’s quintessential Victorian oratorio Elijah drew much praise from Samuel Langford, reviewing it for the Manchester Guardian:

Sir Thomas Beecham conducted Mendelssohn’s “Elijah” on Saturday as freshly as if he had never heard a performance of the work. All the cast-iron rigidity of choral singing which has done so much to make the work a burden to the spirit for many years disappeared in his mobile rhythm, and the true Mendelssohnian impetuosity and vividness, tempered by a poetic and idyllic sense, made the work a delight to the most wearied ears.

Review in the Manchester Guardian, March 11th 1918

In March 1918 the Great War was obviously entering its final months and one of Langford’s final comments underlined that the war had caused difficulties to the choir as choir members, especially the men, were called to service: ‘The concert was one of the few occasions since the outbreak of the war when the choral singing has shown any sings of development.’

Hopeful signs ahead, therefore, and in retrospect it was fortuitous the Hallé’s season had been foreshortened, with the last concert, a performance of various pieces by Wagner, taking place at the end of March. The pages of the Manchester Guardian over the next few months tell us the reason why. The first inklings of problems ahead came literally on the day that the Elijah review was published when a short item in the ‘Abroad’ news round-up section reported the following: ‘Reuter’s Agency is informed by the Spanish Ambassador that the epidemic which has broken out in Spain is not of a serious character. The illness presents symptoms of influenza, with slight gastric disturbance.’

As the first reports of this new strain of influenza came from Spain, it soon became known as the ‘Spanish Influenza’, though there is no evidence that it originated there. The latest research suggests that it probably originated in First World War army camps, with the prime suspect being the Fort Riley army camp in Kansas where soldiers were being trained prior to them sailing across to Europe to fight on the Western Front. Indeed troop ships soon became floating petri dishes for the new virus, and as it later began to tighten its grip, considerable numbers of corpses of those who had succumbed to the disease en route needed to be offloaded once the ships landed in France.

The virus began to spread fast and it soon become obvious that its consequences were worse than suspected back in March. On June 3rd, the ‘Abroad’ section noted that ‘the death-rate in Madrid has more than doubled owing to the prevalent plague of influenza.’

By June 22nd there was the first report of an outbreak in the Manchester area with the headline ‘A New Epidemic – Many Cases in Lancashire – Is it Spanish Influenza?’. 80 cases were reported in a single school in Rochdale. Dr Anderson, the Rochdale medical officer of health described the symptoms in detail with particular reference to the short incubation period, which meant that once the virus took hold it spread like wildfire. The same article reported 1,000 cases in Bacup in the Rossendale Valley, with schools and factories closed.

As the attached report from June 26th shows, four days later cases were showing up in Manchester itself with schools closed in Chorlton-on-Medlock and Salford. Problems also began to appear on Manchester’s tramways as staff shortages began to bite. Important in this report is the reference to the Manchester Medical Officer of Health, Dr James Niven. These were the days before the National Health Service and any co-ordinated national response to such a disease. Decisions on how to tackle the virus were therefore taken at a local level by officers such as Dr Niven, and he was one of the first to recognise the gravity of the situation with regard to the new virus. Notice in the last paragraph his emphasis on people isolating if they felt at all unwell, advice that would be repeated 100 years later and expanded into the concept of ‘social distancing’. He also advocated the disinfecting of handkerchiefs, other articles and rooms associated with the sick. The general consensus is that in preparing this advice, which was published in a leaflet distributed across Manchester, Niven saved many lives that might otherwise have been lost.

Niven’s heroic efforts were memorialised in the 2009 BBC drama documentary ‘Spanish Flu: The Forgotten Fallen’, a copy of which can be seen on YouTube (https://youtu.be/6fRO6zUTFAo?si=hV83TPkCTU5fK_S1). As the virus continued to spread and deepen children and younger adults were particularly at risk. An article on July 1st by the medical correspondent of the Guardian mentioned the previous flu pandemic, the so-called ‘Russian’ flu which spread across the world in 1890. With hindsight this may be what marked out this pandemic as different from the Covid pandemic. It is possible that exposure to the 1890 virus gave the older population a degree of immunity to Spanish flu that the young did not possess. There was no equivalent immunity for the older population to the Covid coronavirus.

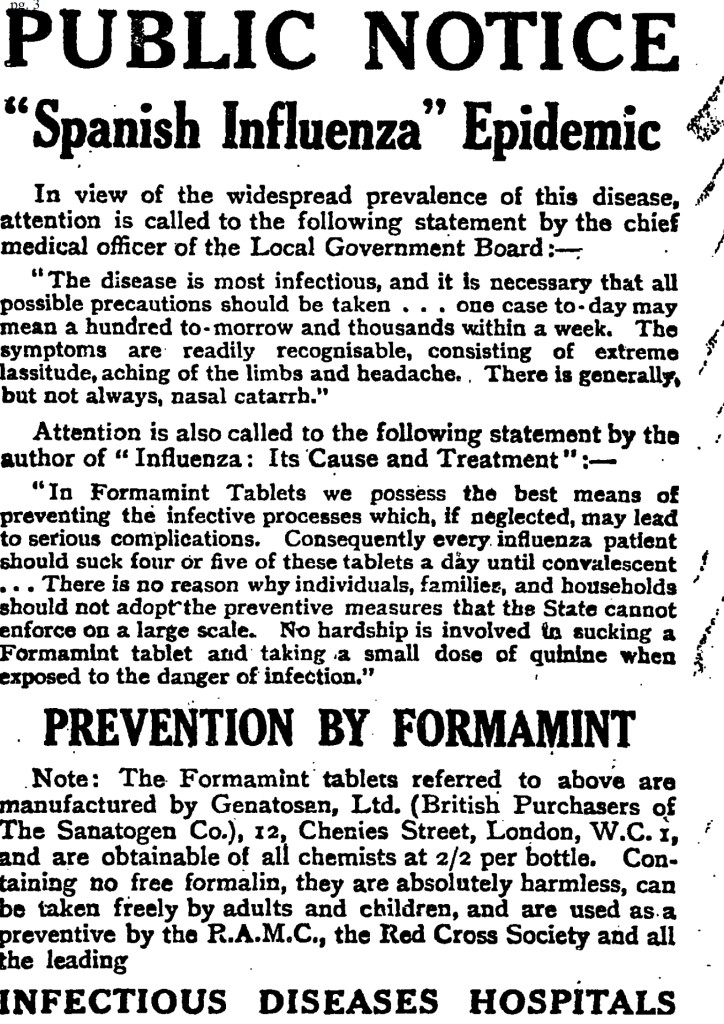

By July 3rd the virus had tightened its grip on Manchester and Salford, with numbers of cases ‘rapidly increasing’ with 15 elementary schools closed in Manchester and public services severely restricted. Deaths were beginning to appear, with Salford reporting five. The following day it was reported that London had seen 67 deaths. By the 9th a third of Manchester elementary schools had closed and deaths were being reported across the country. Advertisements began appearing for supposed remedies to the oncoming scourge, such as the one shown below.

By July 10th, though 100 deaths in Manchester in the previous week had been attributed to influenza and pneumonia, there were signs that the virus was abating. Even so, the virulence of the virus was demonstrated by this following account of an occurrence in Birmingham: ‘A doctor was stopped in the street by a woman who said she was suffering from influenza, and, while he was talking with her, she collapsed and died almost immediately.’ On July 12th a headline read ‘The Influenza – Going, But Not Gone’. The medical view was that ‘the visitation will run its usual course, and may last for two or three months.’

However, the worst of this first wave of the virus had run through Manchester within the space of a month. In a contrast to what would happen a century later, through it all the Hallé and the Hallé Choir were fortuitously off season, and as we shall see later did not miss a single concert. Having said this, however, in another contrast to the later pandemic there was never any blanket closure of concert halls and places of entertainment, as we shall see below. Indeed, on July 5th Samuel Langford reported in the Guardian on the ‘Chamber Music Concert of the Royal College Examinations’ and how ‘the influenza kept one prominent player away’, but that ‘Dr. Brodsky himself [Adolph Brodsky, the principal of the Royal Manchester College of Music] took her place in the two main works.’ The musical world seemed to be continuing as normal.

Deaths continued to increase with July 16th reporting 119 deaths for the week reported in Manchester, an increase of 49 on the previous week, but thanks in part to Dr Niven, the death rate in Manchester as reported on July 18th (28 per thousand) compared favourably with other industrial towns such as Sunderland (46), Oldham (39) and Huddersfield and Darlington (38). On July 18th the Guardian was now confident enough to headline ‘Influenza On The Decline’, though it did report Dr Niven reporting that ‘his recommendations now posted about the city should be strictly followed.’

As with Covid so with Spanish Flu – the virus came in waves and this was only the first wave. By October a second, harsher, wave was underway. One of the early victims was the 70 year old composer Hubert Parry, who caught influenza whilst recovering from septicaemia and died of it on October 7th. On October 24th, the Guardian was reporting severe problems in Liverpool, where 386 deaths from influenza had been reported the previous week, and a growing problem in Manchester.

By October 31st, the virus was ‘steadily spreading’ in Manchester with 10% of pupils absent from elementary schools. The paradox here is that on that very day, the Hallé opened their new season with a concert of Wagner, Franck and Debussy at the Free Trade Hall, conducted again by Thomas Beecham. Samuel Langford reported that there was a ‘fine audience’, and it is true that certainly in the UK and the USA promoters were eager to keep concert halls and other theatrical venues open. As Brian Wise described in BBC Music:

In both London and New York, public health officials sought to quarantine the sick while controversially allowing theatres and concert halls to stay open, provided they were deemed clean and well ventilated. New York theatre patrons were forbidden to sneeze, cough or smoke; several venues were closed for failing to meet the health code. The London Palladium sprayed a ‘germ killer’ between performances.

From article by Brian Wise, BBC Music, December 2022

This was evidently the case in Manchester, despite the fact that Dr Niven had just issued a new leaflet in which he stated, according to the Guardian, that ‘influenza is again prevalent in Manchester, and in warning the public of its “highly infectious” and “very fatal” nature’ described ‘the precautions that should be taken’, precautions that included the avoidance of ‘crowded rooms’! Indeed this wave of the virus proved to be by far the most deadly of the pandemic. In the first wave from June to August 1918 Manchester reported 315 influenza deaths, a number that rose to 1700 in the second wave from October 1918 to January 1919 and fell back to 908 in the third wave from February to April 1919.

November 14th saw the Guardian reporting ‘a steady increase in the number of cases of influenza in Manchester in the last few days’. The very same day saw the Hallé Choir perform in their first concert of the season, under the baton of Hamilton Harty, with a hastily assembled programme to celebrate the armistice of November 11th including excerpts from Mendelssohn’s Lobgesang and Elgar’s Spirit of England, and presumably in memory of the recently deceased composer, Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens. In his review of the performance of this last piece, Samuel Langford implied what may have been flu-related manpower issues: ‘Parry’s “Blest Pair of Sirens” was no doubt wonderful, if we could have heard what it was about; but all pieces in many parts or voices require a dramatic intensity emphasis to make clear, and last night’s performance, though it had sonority, had not this quality.’

November 19th saw reports that ‘influenza is still spreading in Manchester and the death-rate is high’, and two days later the Local Government Board announced new regulations regarding the duration of ‘public entertainments’ in England and Wales. These stated that in any place of public entertainment ‘the entertainment shall not be carried on for more than three consecutive hours, that there shall be an interval of at least 30 minutes between two successive entertainments, and that during the interval the building shall be effectually and thoroughly ventilated.’ It was obviously possible within these regulations for the choir’s Messiah to go ahead in the Free Trade Hall on December 19th, thus ensuring that the tradition of annual performances of this work was maintained. I can only think there must have been a lot of open doors! Two days earlier members of the choir also performed in a performance of excerpts from Rossini’s Stabat Mater in aid of war charities in Houldsworth Hall in Deansgate, conducted by the choir’s choral director R.H. Wilson.

The performance of Messiah was a great success, though Hamilton Harty conducted in place of the advertised Thomas Beecham. Samuel Langford’s review makes no mention of any flu-related difficulties, indeed his only contemporary reference is to ‘feelings of exultation now the Germans are overthrown’, a reference to the Armistice of November 11th. There are few references to the choir within the review but Langford was impressed by the overall effect, though there are hints of a melancholic subtext:

Last night’s performance of “The Messiah” had every kindly geniality. Mr. Hamilton Harty conducted, occasionally setting a pace too lively for unanimity at the outset, but always achieving a nobility of climax and justice of expression as the movements developed. There were other reasons besides his fine interpretation why “For unto us a Child is born” should move the audience greatly as it worked to its magnificent close. But in this and other movements Mr. Harty showed himself finely awake to the sentiments which the time brings uppermost, and this is always a great part of success in the seasonal performance of this oratorio.

Review in the Manchester Guardian, December 20th 1918

So the choir ended one season and began the next with no interruptions to its concert schedule, though the losses caused by both the war and the pandemic must have had a profound effect on the spirit of the choir. As we will see, the Covid pandemic that began in 2019 and hit the UK in earnest in early 2020 may not have caused the same degree of physical loss within the choir, it did cause the longest break in performance the choir has ever experienced, even through the darkest days of two world wars and the devastation wrought by the Spanish Flu pandemic.

2019-2021 – Covid-19

In February 2020 an article appeared in the Guardian outlining what was then known about a troubling new respiratory virus known as Covid-19, short for Coronavirus Disease 2019. It was described as follows:

The virus can cause pneumonia-like symptoms. Those who have fallen ill are reported to suffer coughs, fever and breathing difficulties. In severe cases there can be organ failure. As this is viral pneumonia, antibiotics are of no use. The antiviral drugs we have against flu will not work. If people are admitted to hospital, they may get support for their lungs and other organs, as well as fluids. Recovery will depend on the strength of their immune system. Many of those who have died were vulnerable because of existing underlying health conditions.

From the article ‘What is Covid-19?’, first appearing in the Guardian on February 27th 2020 and updated frequently thereafter

By the time this article first appeared the virus had spread quickly across the globe and there had already been 425,000 people infected by the virus worldwide and 18,000 fatalities.

There were many obvious differences between Covid-19 and Spanish Flu, not least that it was a coronavirus rather an influenza virus, so could not be treated by enhancing existing flu vaccines. Secondly, unlike Spanish Flu which largely affected the young, it was most dangerous for people who were elderly or who had existing morbidities and thirdly, it took longer to incubate than Spanish Flu and could be passed on by people who were showing no existing symptoms. Therefore it was unlikely to race through a community in a short period of time as each wave of the Spanish flu had done – the waves would be longer and deeper.

It was soon obvious therefore that in order to minimise the number of fatalities before a viable vaccine was produced for the virus, there would be a need to protect us from each other via some form of social distancing and thereby limit the spread of the virus from person to person. One by one, the countries of Europe began to introduce such measures, until British Prime Minister Boris Johnson finally announced that a complete lockdown of England would be instituted from March 26th with Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland following suit. Unlike the situation in 1918 where such decisions had to be made very much at the local level, such restrictions could be imposed at a national level, and this alone probably ensured that the final death toll from the virus, tragically high as it was, was significantly smaller than the equivalent toll for Spanish Flu. Even so, images and videos of NHS staff in full PPE battling against the odds to mitigate the suffering of Covid victims as they desperately struggled to breathe became a harrowing daily feature of the news.

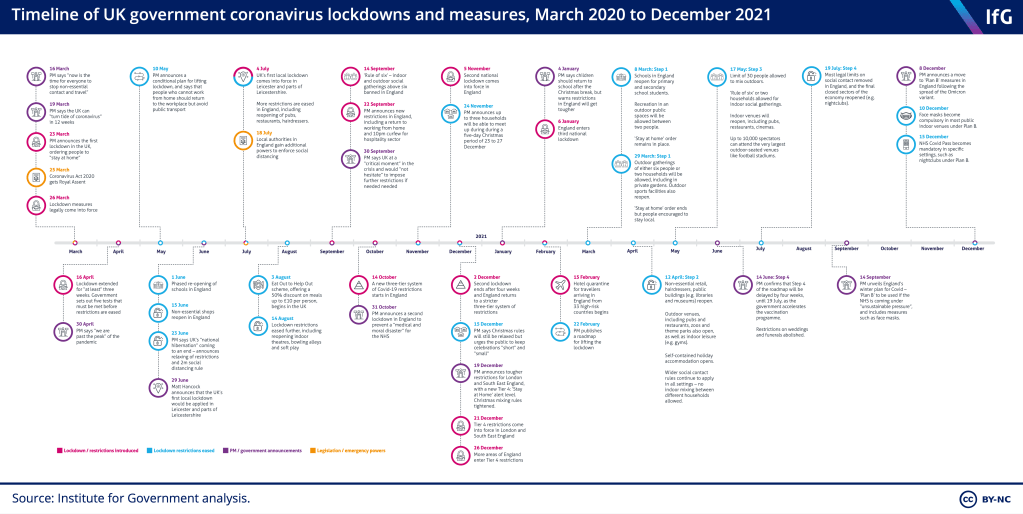

The story of how the world in general and the UK in particular got to grips with the virus via various lockdowns and the fast development of effective vaccines is well known to us all but I thought it would be worth embedding the following chart which shows the timeline of the virus measures during the most harrowing period of the pandemic from March 2020 to the end of 2021. When I come to describe the various ways in which the choir battled the virus you could therefore plot them on this timeline.

2020 was promising to be a good year for the Hallé Choir. It marked the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig van Beethoven and the choir was due to play a big part in the celebrations. The celebrations began in the Bridgewater Hall on January 30th when the choir sang the Angel’s Chorus from Beethoven’s oratorioChrist on the Mount of Olives as a taster for what was going to be a complete performance at Easter, along with a performance (from memory) of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the ‘Choral’. This was the first of four performances of the symphony that the choir would sing with Sir Mark Elder across the country over the coming month, in Manchester, London, Gateshead and Nottingham. In amongst these the choir also sang in a performance with Sir Mark of Act 2 of Beethoven’s only opera, Fidelio, in the Bridgewater Hall on February 19th. All this time, however, we were conscious from news reports of the slow, inexorable spread of the virus and it turned out that the performance of Beethoven’s Ninth in the Royal Concert Hall in Nottingham on February 29th would be the last time the full choir appeared in a public performance in a concert hall until October 2021. On March 16th the choir received the email from the choir administrator Jo PInk that they they had all been dreading, the curtailment of face-to-face choral activities:

We have been following the latest developments in detail. I am very sad to tell you that we have taken the difficult decision to cancel our forthcoming Hallé Choir activities with immediate effect. I am sure you will understand that we have made this decision because of our duty of care to all our Members and a desire to keep everyone safe. At the moment we do not know how long we will be cancelling activities for – we will continue to monitor developments and will be in touch.

From email to choir members, March 16th 2020

The announcement had been expected, particularly as there was evidence that the choral singing environment was an efficient vector for the faster spreading of the virus. What few of us knew at the time was how long we would be out of action for, with many expecting it to be for just a few weeks. However, I did some research on previous serious pandemics such as Spanish Flu and on the characteristics of the virus in terms of infectivity and incubation and came to the conclusion that we would be unlikely to be getting back together properly for the rest of the year. Fellow choir members thought I was being pessimistic but in the event I was sadly wildly optimistic.

However long it was going to take, the choir committee realised immediately that there was a need to keep the choir together as a community, and to keep them singing. The ability to run effective video conferencing online with multiple participants had improved enormously over the last few years and foremost amongst the applications that provided such ability were Microsoft Teams and Zoom. The committee, under the tireless leadership of Lizzy Allerton, tried both in hastily arranged on-line committee meetings and it was soon decided that we should aim to set up Zoom meetings for each Wednesday timed to start when a normal rehearsal would start.

Before these started in earnest, as part of another tack to keep the choir connected, choir director Matthew Hamilton prepared a number of YouTube videos of specific choruses from Messiah to help give us something to work on and assist with the ongoing ‘Messiah from memory’ project. The Zoom choir rehearsals started at the beginning of June. They would serve two purposes, to allow the choir to socialise with each other, often accompanied by large glasses of wine, and to keep the choir singing by revisiting existing favourites and delving into new repertoire. The first of these Zoom rehearsals was held at the beginning of June, with Matthew leading the choir in whilst providing the accompaniment himself from home on his piano. In later Zoom rehearsals when restrictions had somewhat lifted, Matt dialled in from Hallé St Peter’s with David Jones providing the accompaniment. Though it had many positive qualities the main drawback of Zoom was that there is often significant lag between seeing people speak and hearing them speak. It was therefore impractical or us all to sing together unmuted. During the rehearsal sessions the whole choir was on mute apart from Matt, with the result that all any individual choir member could hear was Matt or David’s piano and the sound of themself singing. It was not ideal, but in the circumstances it was enough for the moment.

Through the following weeks the choir gradually worked its way through a number of pieces from the repertoire that would be sent out in PDF form in advance of the rehearsal, and over time Matt introduced us to a lot of unfamiliar repertoire, such as the beautiful part songs of Samuel Coleridge Taylor. In addition to the on-line meetings there was a weekly quiz compiled by a member of the alto section. It proved very popular and produced an intense amount of competition! When the choir were still doing online rehearsals in 2021 there were even occasional guest speakers who took us through their favourite pieces of music, such as Neil Ferris, director of the BBC Symphony Chorus, who took us through Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and former choir director Jamie Burton, who dialled in from his new home in Boston to take us through Vaughan Williams’ moving cantata Dona Nobis Pacem.

To keep the Hallé Choir in the public eye, the Hallé Concerts Society started a process of posting on YouTube videos of a number of acapella items that the choir had performed in concert back in 2019, conducted by Matt Hamilton, including renditions of Eric Whitacre’s Sleep and Charles Villiers Stanford’s The Blue Bird. Most affecting, however, was probably the recording of Moses Hogan’s spirited arrangement of the spiritual The Battle of Jericho, which can be seen and heard in all its glory below. A recording of the complete 2019 performance of Messiah conducted by the Romanian conductor Cristian Măcelaru was also posted on YouTube, but has sadly now been taken down.

One of the singing projects that had to be abandoned as a result of the pandemic was a performance of Beethoven’s short choral masterpiece Meeresstille und Glückliche Fahrt (Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage) with the renowned young Mexican conductor Alondra de la Parra. Through the summer of 2020 the choir worked on producing a virtual rendition of this piece, using Eric Whitacre’s Virtual Choir videos as a template. Choir accompanist David Jones recorded a piano track and Matt Hamilton filmed himself conducting the piece along to the track. Each choir member then filmed themselves singing their part, using David’s track and Matt’s conducting as a guide, after which committee member Sammy Matthewson painstakingly stitched all of the videos together and mixed the sound, placing the singers in a virtual concert hall. The resulting video, which can be seen below, was posted on YouTube by the Hallé Concerts Society on September 2nd, the first ‘real’ performance by the choir in six months.

As summer turned to autumn, even though the world was still some months away from a widely available and effective vaccine, things started to open up, in retrospect perhaps somewhat prematurely with the result that a second lockdown was ordered. The Wednesday Zoom calls continued. As restrictions were again tentatively relaxed running up to December the choir involved itself in two further projects. Firstly, building on the initial recording, a second virtual choir project was started, this time to create a recording of what was then a new unaccompanied arrangement of Silent Night by frequent choir collaborator and organist Darius Battiwalla. Again a piano track and conductor video was prepared, but this time the piano track was of necessity omitted from the final video, leaving the choir somewhat more exposed than they were in the Beethoven recording. Notice that the choir were asked to wear normal concert dress when filming their contribution. Interestingly this was the last time that the tenors and basses of the choir were asked to dress in dinner jackets – since the pandemic the dress code has been simple black shirts and trousers, a development that many in the choir welcomed. The final video was posted on YouTube on December 17th and as you can see and hear below, whilst it was not necessarily perfect, it was an extremely effective recording.

Silent Night turned up again in the second project the choir undertook at this time. The relaxation of restrictions at this time meant both that the orchestra could assemble in a socially distanced manner to play together, and also that the choir could also meet in a suitably separated manner to rehearse. This social distancing meant that if was physically impossible for the whole choir to rehearse together so it was split into four groups and each week each group would rehearse separately in the choir’s rehearsing base at Hallé St Peter’s. The aim was to produce a professionally filmed version of the Hallé’s annual Christmas carol concert that could be made available online for a small fee to the general public.

The recording required a degree of technical subterfuge. On a cold Saturday a few weeks before Christmas, the choir came into the Bridgewater Hall, marshalled by committee members to ensure distancing, and sat spaced around the Bridgewater Hall several seats apart. The idea was that the performances, including an acapella rendition of Silent Night and other pieces accompanied by a socially distanced orchestra on an extended stage and conducted by Stephen Bell, would all be filmed. However, during this initial session only the sound of the orchestra was actually recorded as it would have been impossible for microphones to properly capture the scattered choir. Therefore, during the course of the following week, the choir went back to Hallé St Peter’s in their groups to record the vocals that would be used on the finished film against the orchestra track recorded the previous Saturday. The individual group recordings were then merged and added to the orchestral recording and synchronised with the film recording. Thus, because I myself was not able to make the recording session, I can be seen in the final video but not heard! What resulted was an extremely professional and polished concert recording that belied the jiggery pokery that was required to produce it. It included readings from the likes of poet Lemn Sissay, musician Guy Garvey of the band Elbow and choir members, plus further sung contributions from the Hallé Children’s Choir and Hallé Youth Choir that had been both filmed and recorded in Hallé St Peter’s.

Sadly, that was the highpoint of the winter for the choir. Christmas 2020 saw a further complete lockdown and as the choir entered 2021 it was uncertain when, if ever, it would be able to rehearse and perform together in person again. However, December 8th had seen the first vaccination using the new Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine and soon a further vaccine emerged from AstraZeneca. Slowly through the late winter and spring of 2021 as the population got vaccinated, whilst cases remained stubbornly high, the number of deaths attributable to Covid began decline and the symptoms of those who caught Covid but had had the vaccine became less severe. The prospects for some sort of resumption of activities for the 2021/22 season were beginning to look more encouraging, and by July 2021 the choir were finally able to make two public appearances of sorts, albeit in both cases in very strange circumstances.

Though by this time most of the choir had been vaccinated once if not twice, because of the continuing perceived risk of spreading the virus through singing, the possibility of rehearsing the whole choir indoors was still many months away. However, there was nothing to stop gathering to rehearse outdoors. The search was therefore on to find a venue suitable for 100-plus members to get together and sing. The unlikely answer to the search came in the form of Stand E at the Old Trafford Cricket Ground, and it was with a mixture of excitement and amusement that the choir assembled there on June 30th for their first full rehearsal since March 2020. Whilst the choir still had to obey social distancing protocols and sit a few seats apart the venue proved an inspired choice with the raked seating providing excellent sightlines to Matthew standing near the boundary edge and the overhanging roof amplifying the choral sound.

During the course of the Old Trafford rehearsals the choir ran through a few staples of the choral repertoire and even began work on Igor Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, which was scheduled to be the first work the choir would perform back in the Bridgewater Hall were concerts to be able to resume in the autumn. The very first moments of the very first rehearsal were in their own way as memorable as anything during the pandemic. The choir began with a quick warm up which prompted staff to begin to emerge from the pavilion away to the choir’s left and guests to come out onto the balconies of their rooms in the hotel to the right of the pavilion. Following the warm up Matthew led the choir in a complete run through of Parry’s I Was Glad accompanied by David Jones on an electric keyboard. At the end of the piece there was a brief pause before spontaneous applause and cheering echoed across the outfield from the direction of the pavilion and hotel and the choir suddenly realised that they had given their first public performance for 18 months – a very satisfying feeling.

An incident from a few weeks later was memorable in a very different way. Whilst for the first Old Trafford rehearsal the keyboard had been perched high up in the stand, for this rehearsal it was at the bottom just inside the boundary edge, with David Jones just behind Fanny Cooke who was taking that particular rehearsal. On the other side of the ground sprinklers gently watered the outfield. All was going well until about 45 minutes into the rehearsal when a sprinkler erupted a few yards from David, soaking him and the keyboard in an instant and causing the immediate and total collapse of the rehearsal. Thankfully the incident was recorded on camera for posterity!

Through the course of the spring and summer of 2021 performances began to resume in theatres across the country, albeit still with socially distanced audiences. I myself saw a number of ballet performances across the country during that period, with strict protocols around which dancers could dance with which and regular Covid testing to ensure the safety of the performances. It was the world of dance that in July gave at least a portion of the choir the chance to perform in front of a paying audience for the first time since February 2020.

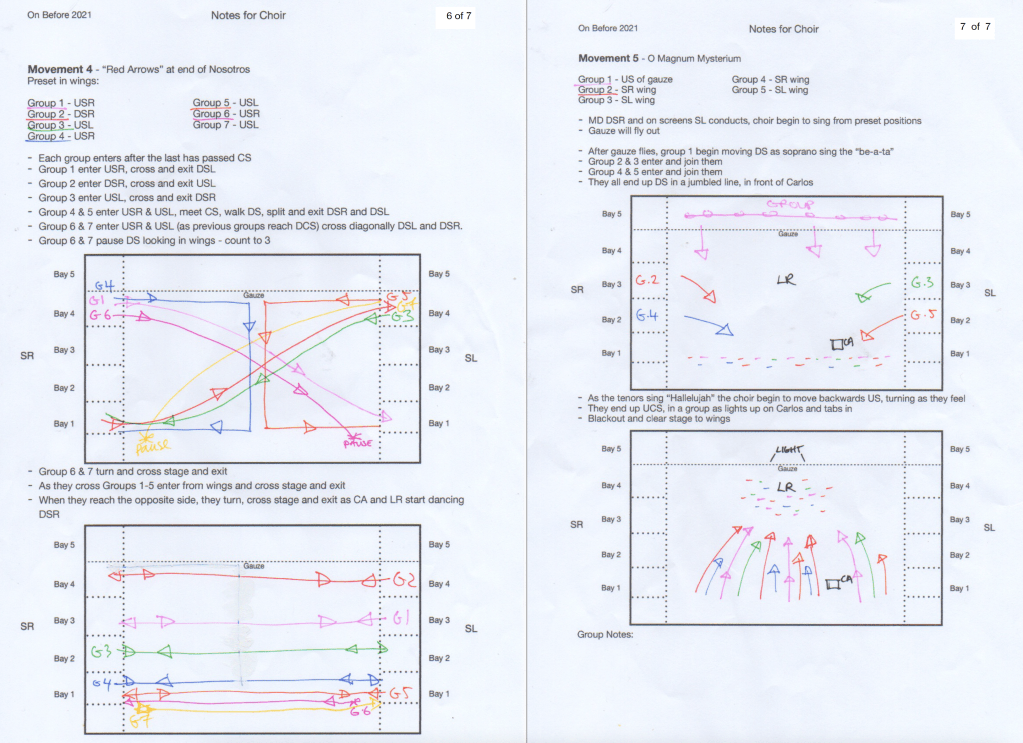

Carlos Acosta is a legend of the ballet world, born into poverty in the backstreets of Cuba but given a lifeline as a young boy by the world of ballet, even if during much of his early training he would by his own admission rather have been playing football or dancing hip-hop. His talent brought him to English National Ballet, Houston Ballet and eventually in 1998 to the Royal Ballet in London where he danced for the next 18 years creating many memorable roles. Following his retirement from the Royal Ballet he moved to Somerset with his wife and young family but continued his association with ballet, forming the Acosta Danza company back in his native Cuba and in 2020 taking over the directorship of Birmingham Royal Ballet. Crucially he also continued dancing and in the summer of 2021 decided to revive On Before, a show that he had devised a few years previously in memory of his late mother. It was a two-hander in which he would be dancing with Laura Rodriguez from his Acosta Danza company, and it also required during the final passage of dance for voices to be onstage singing Morten Lauridsen’s beautiful setting of O Magnum Mysterium. They therefore needed a small choir for the project and as Matt Hamilton had been engaged as musical director for the project, which would be visiting several venues during the course of the summer, the Hallé Choir was the obvious choice of choir for two performances at The Lowry in Salford. As the performance would not be socially distanced, the choir would need to test themselves for Covid before every rehearsal and performance and mask themselves when not actively performing.

So July 18th saw around 50 volunteers from the choir assemble in Hallé St Peter’s, chairs spread far and wide, for their only chance to run through the piece before the stage rehearsal at the Lowry. The choir had been primed to learn the piece in advance as it would need to be sung from memory. During the course of the evening it began to take shape, helped no doubt by all the Handel Messiah memorising that the choir had been doing. Two days later was the choir’s first stage call and they assembled at the Lowry, masked and Covid-tested, expecting just to stand on stage and sing O Magnum Mysterium and the end of the performance. Little did they realise that in most of the five linked movements of On Before, each created by well-known choreographers such as Will Tuckett, Russell Maliphant and Carlos himself, the choir would actually be part of the performance, crossing the stage or forming often quite complex patterns around the two dancers. In the final O Magnum Mysterium things got especially complicated, with the choir standing in the wings either side of the stage having to pitch their initial note from nowhere and begin singing and watching Matt conducting from stage-side monitors. They then had to turn and slowly walk on stage, thereby losing sight of Matt until they could pick him up again on the monitors on the lip of the circle, gradually moving to the front of the stage for the climax whilst Carlos and Laura danced their choreography around them. As the music gradually subsided at the end of the piece the choir turned and slowly walked upstage, gradually forming a huddle around a crouching Laura as the piece ended.

The choir ran through the movements successfully but it was with enormous trepidation that they turned up again on July 21st for the first performance, armed with sheets marked up with the choreography, but anxious not to make a complete mess of it. In the event, encouraged by Carlos who throughout the project was a welcoming and inspiring presence, it worked perfectly. It was a remarkable experience for the choir, received rapturously by audiences on both the 21st and 22nd. Though the audience in the circle were obeying social distancing, for the first time that week venues were allowed to designate areas for full occupancy, so all the seats in the stalls were occupied. When the lights went up as the dancers and the choir took their bow they could see rows of people in front of them standing and cheering. Though the Covid pandemic was far from being over, the choir emerged from the Lowry after a couple of team photographs and armed with programmes signed by both Carlos and Laura wondering if the previous two years had been a dream.

On Before was a remarkable way for the choir to end the period of formal Covid restrictions, but September 2021 saw the return of some true form of normality with the start of rehearsals for the new 2021/22 season, for which all audience restrictions had been lifted other than a recommendation for them to stay masked. As mentioned earlier, the first work due to be performed was Stravinsky’s sparse and mystical Symphony of Psalms, with Sir Mark Elder as conductor. For the first rehearsals most of the choir masked themselves when moving around and the chairs were more widely spread than usual, but finally the whole choir were actually rehearsing in earnest indoors again. It took time for the choir properly to regain its voice, but slowly through September the choir’s confidence returned. Many Covid protocols remained however. Before the rehearsals in concert week, each member of the choir took specially provided Covid PCR tests that were formally processed in a laboratory, with anyone testing positive barred from performing. In performance, as can be seen from the photograph, there was one free seat between every choir member.

The concert on October 9th was a success, both from an audience point of view, and from the choir’s as they launched themselves into the post-Covid world. Rebecca Franks, writing in the Times, headlined her review ‘a welcome return for the Hallé Choir’. Peter Connors, reviewing the concert for Bachtrack, said it all:

The Hallé Choir has not sung together in the Bridgewater Hall with an orchestra since February 2020 so their performance of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms was bound to be special. With some 120 singers spread out behind the orchestra, keeping a distance of 1m apart, they made an impressive sight and an even more stirring sound. They have missed singing and audiences have missed hearing them.

Peter Connors reviewing Symphony of Psalms on bachtrack.com, October 10th, 2021

December 2021 saw the return of Messiah and yet another reminder that Covid was still very much an issue, as conductor Sofi Jeannin, chief conductor of the BBC Singers, managed to get to the UK from her home in Paris just in time before further restrictions came into place in France which would have been prevented her travelling. It was a hugely enjoyable concert for the choir under the charismatic Jeannin, with the choir tantalisingly close to their target of doing the whole piece from memory. A real indicator that the world was almost back to normal, however, was the return of the annual Christmas carol concerts later that month, where the choir joined with the youth choir and children’s choir. Any suggestion of socially distanced choir seating was abandoned, which did cause a degree of concern within the choir, though each choir member was instructed to mask up when not singing and to sing with masks on during the audience carols to encourage the audience to do the same.

At the time of writing, in January 2024, choir performances are back to normal, and have been for some time. However, there are still large numbers of cases of Covid being reported as new variants break through the bounds of the vaccine, though effects of the vaccine mean that symptoms are almost always mild and hospital admissions are generally restricted to those who are in some way compromised. The Economist reported in November 2023 that whilst there have now been nearly 7 million deaths worldwide reported to have been caused directly by Covid-19, there have been between 18 and 33 million excess deaths during that period that may be attributable to Covid. Whilst Covid deaths are considerably smaller in number than those caused by Spanish Flu, where even on the lowest estimate of directly attributable deaths (17.4 million) the virus killed 1% of the world’s population, improved health care, health advice and vaccinations during Covid-19 explain much of that discrepancy. They do not hide the fact, however, that the Covid-19 pandemic was a cataclysmic event. The nature of singing means that any respiratory disease that spreads quickly is a potential danger. That the Hallé Choir has been able to navigate two pandemics of such diseases over the last 100 years and a bit is a testament to its resilience and fortitude, though that testament must stand alongside the grief that we feel over losing so many loved ones to these two terrible diseases.

References

Anon, ‘Timeline of UK government coronavirus lockdowns and restrictions’, Institute for Government, updated December 2022 https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/data-visualisation/timeline-coronavirus-lockdowns

Anon, ‘The pandemic’s true death toll’, The Economist, updated November 18th 2023 https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/coronavirus-excess-deaths-estimates

Archives+, The “Spanish Flu” pandemic and Manchester, (Manchester: Manchester Libraries, 2020) https://manchesterarchiveplus.wordpress.com/2020/05/24/the-spanish-flu-pandemic-and-manchester/

John M Barry, ‘The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications’, Journal of Translational Medicine, 2:3 (2004) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC340389/

Sarah Boseley, Hannah Devlin and Martin Belam, ‘What is Covid-19?’, The Guardian, updated March 20th 2020 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/27/what-is-covid-19

Justin Hardy (Director), Peter Guiness & Peter Harness (Writers), ‘Spanish Flu: The Forgotten Fallen’, BBC (2009)

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960).

Matthew Smallman-Raynor, Niall Johnson and Andrew D. Cliff, ‘The Spatial Anatomy of an Epidemic: Influenza in London and the County Boroughs of England and Wales, 1918-1919’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, Vol. 27 No. 4 (2002), pp. 452-470 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3804472

Laura Spinney, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World (London: Jonathan Cape, 2017)

Dylan Vance, Priyanka Shah, Robert T Sataloff, ‘COVID-19: Impact on the Musician and Returning to Singing; A Literature Review’, Journal of Voice, 37(2) (2023) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33583675/

Brian Wise, ‘Spanish Flu: how the deadly pandemic impacted musicians’, BBC Music, December 2022 https://www.classical-music.com/articles/spanish-flu-impacted-musicians

Reviews from

Guardian Archives, provided by Manchester Library and Information Services

Bachtrack bachtrack.com

The Times www.thetimes.co.uk

Hallé Choir videos from the Hallé YouTube channel

Leave a comment