Over the years since the beginning of the Hallé Choir one might have expected that the chorus of such a prestigious orchestra as the Hallé would have sung in countless world premieres and first performances. However, at least for the first hundred years or so of the choir’s existence such occasions were relatively rare.

Why might this be? In the first of these blogs I talked about how, following the long-running example of the Three Choirs Festival, music festivals began appearing across the length and breadth of the land through the 19th century. Attached to many of these festivals was a festival chorus and it became a regular occurrence for the festivals to commission new works from the established composers of the day that involved the choir. Especially through the 20th century there have also been many examples of choral works being commissioned to celebrate special events or anniversaries, either significant dates in the history of particular choirs, or of other organisations and institutions. In other words, big choral premieres were most definitely ‘events’, and I personally particularly remember the thrill of participating for the first time in just such an event to celebrate the 900th anniversary of Chester Cathedral in 1992. There is something special about hearing something for the first time, but there is something even more special about singing something for the first time.

Table 1 shows a list of some of the choral works that were first brought into the world at such events during the lifetime of the Hallé Choir, many of which are still very much part of the Hallé Choir’s standard repertoire and that of choral societies throughout Britain.

| Year | Composer | Work | Occasion |

| 1886 | Antonin Dvorak | Saint Ludmila | Leeds Festival |

| 1893 | Edward Elgar | King Olaf | North Staffordshire Music Festival |

| 1898 | Edward Elgar | Caractacus | Leeds Festival |

| 1900 | Edward Elgar | Dream of Gerontius | Birmingham Music Festival |

| 1903 | Edward Elgar | The Apostles | Birmingham Music Festival |

| 1906 | Edward Elgar | The Kingdom | Birmingham Music Festival |

| 1907 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Toward the Unknown Region | Leeds Festival |

| 1910 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | A Sea Symphony | Leeds Festival |

| 1911 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Five Mystical Songs | Three Choirs Festival |

| 1912 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Fantasia on Christmas Carols | Three Choirs Festival |

| 1913 | Hamilton Harty | The Mystic Trumpeter | Leeds Festival |

| 1930 | Arthur Bliss | Morning Heroes | Norwich Festival |

| 1931 | William Walton | Belshazzar’s Feast | Leeds Festival |

| 1936 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Five Tudor Portraits | Norwich Festival |

| 1936 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Dona Nobis Pacem | Centenary of Huddersfield Choral Society |

| 1948 | Benjamin Britten | Saint Nicolas | Centenary of Lancing College |

| 1950 | Gerald Finzi | Intimations of Immortality | Three Choirs Festival |

| 1950 | Herbert Howells | Hymnus Paradisi | Three Choirs Festival |

| 1954 | Ralph Vaughan Williams | Hodie | Three Choirs Festival |

| 1961 | William Walton | Gloria | 125th anniversary of Huddersfield Choral Society |

| 1962 | Benjamin Britten | War Requiem | Consecration of new Coventry Cathedral |

| 1992 | John Tavener | We Shall See Him As He Is | 900th anniversary of the founding of Chester Cathedral |

| 2000 | Karl Jenkins | The Armed Man | Commissioned by Armouries Museum for the Millennium celebrations |

| 2000 | Colin Matthews | Aftertones | Commissioned by Huddersfield Choral Society to mark the Millennium |

In comparison, for the Hallé Choir, excluding the plethora of new arrangements and settings that appear regularly in the choir’s Christmas concerts, premieres of major works have historically been relatively few and far between, and premieres of works that have remained in the repertoire even rarer. In his 1960 history of the orchestra, Michael Kennedy lists the works that had been premiered or received their first English performance at Hallé concerts in Manchester. These include some significant works, such as the premieres of Elgar’s First Symphony in 1908 and Vaughan Williams’ Eighth Symphony in 1956, and first performances of Sibelius’ Second Symphony (1905), Mahler’s Ninth Symphony (1930), Shostakovich’s First Symphony (1932), and Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini in 1935 (with the composer as the soloist).

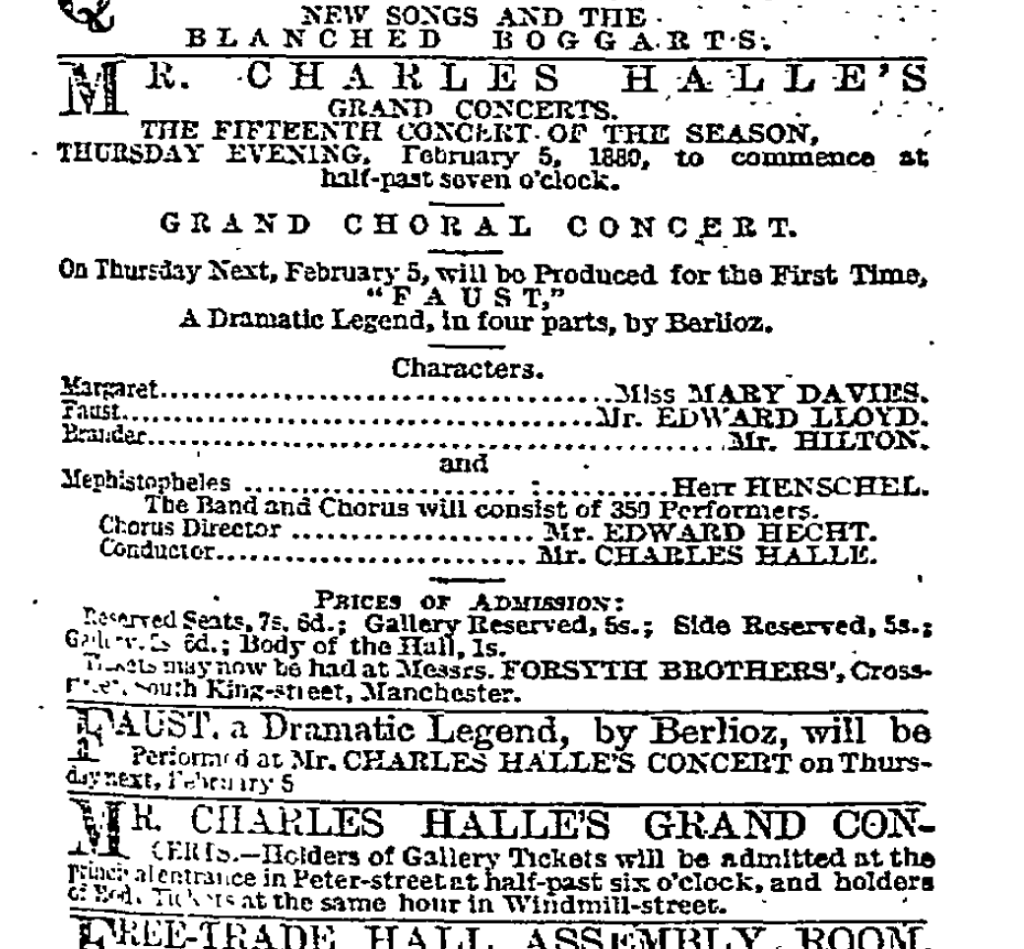

However, of all the works Kennedy lists, only three involved the choir. Of these, two were premieres involving the choir, the Sinfonia Antartica, which I discussed in a previous blog, and Constant Lambert’s Rio Grande. I will look at Rio Grande in more detail in the second part of this blog, when I will also look at how over the last thirty years there has been a significant rise in the number of world premieres, first performances, and premiere recordings that the choir has been asked to do. Meanwhile, I will devote the rest of this first part of the blog to the last of the three choral works in Kennedy’s list, Berlioz’ La Damnation de Faust (‘The Damnation of Faust’), given its first complete UK performance by Charles Hallé and the Hallé Orchestra and Choir on February 5th, 1880.

Here is Charles Hallé talking about the beginning of his relationship with the composer Hector Berlioz in Paris in the 1830s:

‘The most important friendship I formed at that time (or it may have been at the end of 1837) was that with Hector Berlioz—’ le vaillant Hector’ as he was often called—whose powerful dominating personality I was glad to recognise. How I made his acquaintance is now a mystery to me—it seems as if I had always known him—I also wonder often how it was he showed such interest in an artist of so little importance as I then was; he was so kind to me, and, in fact, became my friend. Perhaps it was because we could both speak with the same enthusiasm of Beethoven, Gluck, Weber, even Spontini, and, perhaps, not less because he felt that I had a genuine admiration for his own works.’

Charles Hallé, from ‘Life and Letters of Sir Charles Hallé’

Hector Berlioz was one of the most important composers of the post-Beethoven Romantic age, a composer that wore his heart on his sleeve in a series of rich, dense, exciting and occasionally gloriously overblown works such as the Symphonie Fantastique, which documented his at the time unrequited infatuation with the Irish actress Harriet Smithson. The passion that lay behind his music is best evidenced by this quote attributed to the composer: ‘To render my works properly requires a combination of extreme precision and irresistible verve, a regulated vehemence, a dreamy tenderness, and an almost morbid melancholy.’

According to Rachel Hewerton, Charles Hallé was introduced to Berlioz via a mutual acquaintance, Stephen Heller, soon after Hallé arrived in Paris, and as can be seen in the above quote a strong musical bond formed between the two. This is evidenced by the fact that Hallé was at the first performance of Berlioz’ Requiem (‘Grande Messe des Morts’) in 1837 and also attended the rehearsals and first performance of his Roméo et Juliette symphony in 1839. Indeed, in his memoir Hallé remembers the famous occasion in the first performance of the Requiem when, as he felt the performance was falling apart, Berlioz snatched the baton from the conductor during the ‘Tuba Mirum’ and began conducting himself.

After Hallé moved to Manchester and began programming concerts with his new orchestra, the works of Berlioz became a staple part of the repertoire. He never attempted to put on the monumental Requiem for practical reasons (‘the placing of four orchestras at the corners of the principle one is impossible in our concert rooms’), but other pieces began to appear on Free Trade Hall concert programmes, often in excerpted forms.

| Selection | Work | Location | Date |

| Marche des pèlerins | Harold en Italie | Manchester | Dec 18th, 1855 |

| Marche des pèlerins | Harold en Italie | Manchester | Feb 20th, 1858 |

| La reine Mab | Roméo et Juliette | Manchester | Dec 30th, 1863 |

| Scène du Balcon [sic] | Roméo et Juliette | Manchester | Dec 30th, 1863 |

| Marche des pèlerins | Harold en Italie | Manchester | Dec 8th, 1864 |

| Roméo seul / Scène d’un Bal | Roméo et Juliette | Manchester | Feb 1st, 1866 |

| Scène d’un Bal | Symphonie Fantastique | Manchester | Nov 22nd, 1866 |

| Scène aux Champs | Symphonie Fantastique | Manchester | Jan 31st, 1867 |

| Scène du Balcon | Roméo et Juliette | Manchester | Jan 30th, 1873 |

| Scène du Balcon | Roméo et Juliette | Edinburgh | Feb 14th, 1874 |

| Complete | Harold en Italie | Manchester | Jan 28th, 1875 |

| Complete | Harold en Italie | Manchester | Jan 17th, 1878 |

| Complete | Harold en Italie | Liverpool | Jan 29th, 1878 |

| Complete | Symphonie Fantastique | Manchester | Jan 9th, 1879 |

| Complete | Symphonie Fantastique | Liverpool | Jan 14th, 1879 |

| Complete | Roméo et Juliette | Manchester | Dec 29th, 1881 |

Table 2, compiled by Hewerton, shows how he gradually moved from playing excerpts to playing complete works as he gained confidence in the audience’s ability to absorb them. The same applied, eventually, to La Damnation de Faust. This monumental work, which melds together aspects of opera, oratorio, ballet and the symphonic repertoire, was described by Berlioz as a ‘légende dramatique’ and first performed in 1846. The particular legend being dramatised was Goethe’s Faust, whose titular character sells his soul to the Devil in return for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasure. The three main singing roles are Faust himself, the Devil (as ‘Mephistopheles’), and Marguerite, the woman with whom Faust becomes infatuated. The work also includes a substantial role for a chorus who through the course of the drama play a bewildering variety of roles in a variety of locations – Hungarian peasants, an Easter choir in the north of Germany, drunken revellers in a Leipzig tavern, a chorus of ‘gnomes and sylphes’ singing Faust to sleep on the banks of the Elbe, a mixed chorus of soldiers and students, a group of gossiping neighbours, demons in Hell singing in a made up infernal language (see score example), and finally a choir of celestial spirits (including a children’s choir) as Marguerite ascends to heaven in the work’s final scene. The multiplicity of scenes and specific stage directions suggests it should work as an opera, and it has been staged as such (most recently at the Royal Opera House, for example, in 1993, and at Glyndebourne in 2019), but it is far more often performed as a concert piece, and this is how Charles Hallé conceived it.

What was clear by 1880 was that Hallé was the foremost champion of Berlioz’ music in the country, such that his decision in that year to put on a full performance of the work was no surprise. Indeed, its first performance was soon followed by full performances of the Romeo et Juliette symphony and the oratorio L’Enfance du Christ.

As with other large-scale Berlioz works, Hallé began by introducing his audience to small sections of Faust, beginning back in the time of the Gentlemen’s Concerts and the Art Treasures Exhibition, where the ‘Ballet des Sylphes’ and the famouns ‘Marche Hongroise’ (also known as the ‘Racoczy March’) were programmed. During the first season of the Hallé Orchestra in 1858 there were six performances of these two works, and according to Hewertson, the ‘Ballet des Sylphes’ was considered one of the top ‘hits’ of the season. By 1877 the ballet had been performed a grand total of seventeen times. In comparison the march, which subsequently has proved to be the more popular selection from the work across the musical world, was performed seven times.

The omens were not necessarily propitious. Two years before, in 1878, the French conductor Jules Pasdeloup and his orchestra gave a nearly full performance of the work in London using the original French text. The music critic of the Times was not impressed by the work, the size of the audience, or the quality of the chorus:

‘In choosing so strange a work as Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust for production at his first concert M. Pasdeloup has sacrificed his personal interests to his love for art or for a particular phase in art. Many amateurs would have been interested in seeing the celebrated chef d’orchestre conduct one of Beethoven’s or Schumann’s symphonies and in comparing his readings to those familiar works with those of Mr. Manns or Mr. Cusins. The works of Berlioz being, on the other hand, all but unknown in this country, the attention of the―we are sorry to say―extremely scanty audience was directed towards the composition rather than towards the conductor. Another drawback was the all but inevitably imperfect nature of the performance. The time which the overworked chorus at Her Majesty’s Theatre could give to the rehearsal of such a work was naturally wholly inadequate, and under the circumstances it is a matter of surprise that an actual catastrophe was at least avoided.’

The Times 4th June, 1878

Indeed, according to Michael Kenndy, when Hallé made known his ambition to perform the complete work in Manchester his long-serving chorus-master Edward Hecht argued against it, fearing that the Manchester public ‘were not ready for it.’ However, Hallé had a cunning plan. Knowing the norm in England was where possible to sing choral works in English rather than the language in which the work might have been written, both for ease of performance by choirs and to enable the audience to easily follow the story, he commissioned his daughter to write a translation of Faust from French to English. According to Hewerton this also also chimed with ‘Hallé’s educational ambition in Manchester’ in that ‘hearing Faust in English, audiences were treated to a thrilling tale of morality that played directly into the Victorian ideals of self betterment and moral upbringing.’

The first performance was set for February 5th, 1880 with the Manchester Guardian advertising that ‘The Band and Chorus will consist of 350 performers.’ The sense of anticipation before the concert was palpable, if the correspondent in the Manchester Guardian writing on the day of the concert is to be believed. After describing the work in detail, he concludes that the paper’s readers will find ‘that there is here ample opportunity for the display of the dramatic instinct in the musician. A cursory glance at the music has greatly interested us, but we shall reserve our notice of this portion of M. Berlioz’s work until after we have heard this work this evening with orchestral accompaniments.’ According to Hallé’s son Charles E. Hallé, news of the concert raised a stir not just in Manchester but further afield. His description of the concert and its build up is worth quoting at length, as it shows that the preparation for the concert was far more meticulous than would appear to have been the case with Pasdeloup, resulting in a performance that was nothing short of a triumph. It comes from Life and Letters of Sir Charles Hallé, a book based on a memoir written by Charles Hallé himself to which his son added details of Hallé’s life subsequent to his writing of the memoir, including this concert:

‘In 1880 my father brought out a work at his orchestral concerts in Manchester, the production of which gave him the greatest pleasure and interest; this was Berlioz’s ‘Faust.’ The Hungarian March and the ‘ Ballet des Sylphes’ were well known, as they had often been given at previous concerts; but to give the work in its entirety had been my father’s ambition for years, and he at last ventured on it in spite of the doubts expressed by many of his friends as to its proving a popular success. The concert excited much interest throughout England, and many well-known musicians repaired to Manchester to hear the first performance of a work which had been so much discussed, and about which so many contrary opinions were held.

‘The performance, which had been preceded by many careful rehearsals, was at all points magnificent, and reflected the greatest credit upon both band and chorus, whilst the principal vocalists, Miss Mary Davies, Mr. Lloyd, Mr. Hilton, and Mr. Henschel rendered the solos admirably. The work was received with so much enthusiasm that my father gave it a second time during the same season, a very rare proceeding on his part.

‘I went to Manchester for the first performance of Faust and being anxious to know something about it before the concert took place in the evening I attended the rehearsal. A little incident occurred which revealed to me my father’s wonderful accuracy of ear, and which I may be pardoned for repeating. In the second part of ‘ Faust,’ when the hero of the legend meets his doom and is consigned to the infernal regions, there occurs an interlude for the orchestra expressive of the exultation felt by the denizens of hell over their latest victim. When I first heard this piece I felt inclined to think my father had given carte blanche to every member of his band to make any noise he liked, provided it was loud and of a horrible nature.

‘When it was over, what was my astonishment to hear my father quietly say: “The second clarinet played an E flat instead of an E natural in the eighth bar. I hope he will take care not to do so at the concert this evening!”‘

Charles E. Hallé, from Life and Letters of Sir Charles Hallé

While these comments may be coloured somewhat by coming from a dutiful son, there is no doubt that the evening was a resounding success. To quote at length again, here is an extract from the long review of the concert published in the Guardian two days after the concert. What is noticeable from a choral perspective is his recognition of the contribution of the chorus in their various guises to the success of the evening and, echoing Charles E. Hallé, the scrupulousness of Hecht’s preparation of the choir. Those of us who have sung the work will also recognise his appreciation of the difficulty of the ‘Faust’s Dream’ section of the work:

‘It is long since we have noticed such unmistakeable enthusiasm as was displayed during the whole evening. The rapidly changing and broadly contrasted scenes of the “Faust” legend afford a singularly favourable medium for the display of a genius of the somewhat erratic, and certainly unconventional, type of Berlioz. We might doubt his capacity for sustained and continued effort, but we need only one specimen of his work to discover a wonderful power of fantastic expression. There is something of the showman in his nature. Every subject is presented in its broadest lines, heightened by strongly contrasted colours, and set off by lurid lights. And of all men that have lived Berlioz perhaps possessed the greatest mastery over the orchestra as a medium for descriptive power.’

‘The effect of the [Rakoczy] march was electric. An audience usually somewhat cold and receptive merely were aroused to such unwonted enthusiasm that nothing short of an encore would pacity them.’

‘The drunken roystering of Brander and his companions is most cleverly brought to a climax in the fugue which they improvise. Some of the stricter of the Germans, who formed so large a portion of the audience, objected to the truth of the picture. “After all, it is but a Frenchman’s conception of the subject.” This may be perfectly correct, but it does not prevent the enjoyment of those who are less literal in their expectations of demands.’

‘…we have a wonderfully conceived movement, entitled “Faust’s Dream,” in which the fiend and his imps present Margaret’s image to Faust. This is one of the most difficult numbers in the work, full of cross tempi, and needing the most perfect rehearsal and the watchful attention of the conductor for its success.’

‘The actual meeting of the lovers is, perhaps, the weakest scene in “Faust,” but the trio and chorus at the close of part 3 is worthy of comparison with any other portion of the work. The whole of part 4 is marvellous. It is utterly impossible for us within our limits to attempt to do justice to the dramatic intensity of the “Ride to the Abyss.” Its horror is unparalleled in the range of musical expression, culminating in a crash so awful that the precipitation into the gulf becomes visible to the mental eye; while the demoniac welcome Mephistopheles and his victim receive is a fitting conclusion to such a scene. The pure beauty of the melody of Margaret’s “Apotheosis” comes like sunshine and the sweetness of the “upper air” after the lurid blackness of such a pandemonium.’

‘The work was magnificently given. Immense pains had been taken with its rehearsal, which were amply justified by the result.’

Manchester Guardian, February 7th 1880

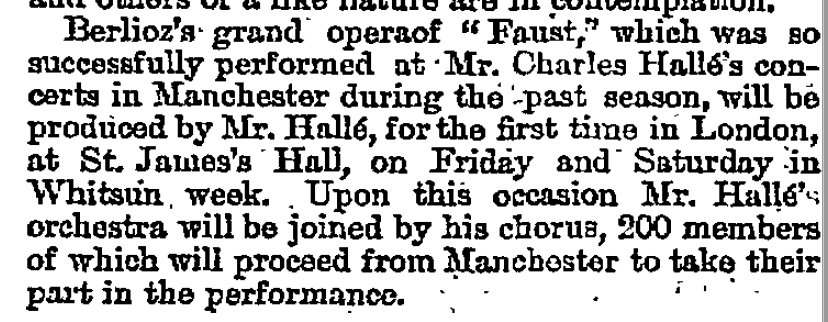

Such was the success of the concert that it was repeated at the Free Trade Hall in March, and on May 13th, the Guardian announced an important event. Hallé had that season been taking his orchestra down to perform in London, but following the success of Faust he was going to take his orchestra and choir down from Manchester for not one but two performances of La Damnation de Faust at St James’s Hall on May 21st and 22nd. Nowadays, the Hallé Choir appear regularly in London, particularly, as recorded in a previous blog, at the BBC Proms, but in 1880 a trip down to London was much more of a special event. Judging by the correspondent of the Times, reviewing the concert on the 21st, the choir did Manchester proud. Any memory of Pasdeloup’s performance two years before was banished. When talking about ‘rehearsing chorus and orchestra separately’ he is referring to the then common practice of rehearsing them separately not just until a final one or two orchestral rehearsals as is done now, but until the performance itself!

‘The performance thus suggested took place on Friday night at St. James’s-hall, and the result was such as fully to warrant Mr. Hallé’s confidence in the merits of the work and the taste of the London public. Not only was the hall crowded, but the attention with which everything was listened to and the enthusiasm excited by certain passages tended to show that English amateurs no longer reject music on account of its originality or even eccentricity. Mr. Hallé’s zeal and spirit of enterprise in arranging the performance cannot be commended sufficiently. Orchestra and chorus, consisting together of 300 performers, had been brought up to London, and the fire and accuracy with which some of the most difficult music perhaps ever written was rendered testified to the care and the intelligence of the conductor. The services of the chorus master, Mr. E. Hecht, should not be forgotten. As regards freshness of voices and perfect ensemble, the performance on Friday night has indeed seldom been matched in London, where the barbarous custom of rehearsing chorus and orchestra separately still prevails.

‘…We need not say that, as a whole, the rendering on Friday night was infinitely superior to the only one previously given in London – at Her Majesty’s Theatre in June, 1878. On that occasion the celebrated M. Pasdeloup was the conductor, but he had been unable, in one or two rehearsals, to make the chorus acquainted with more than the rudiments of its task, and with the exception of Miss Minnie Hank, an excellent Marguerite, the soloists were equally unsatisfactory.

‘…Mr Hallé and his chorus and orchestra must once more be congratulated on the admirable rendering of so difficult and important a work.’

The Times, May 24th 1880

A roundup of the 1879/80 concert season in the Musical Times noted these concerts as a particular highlight: ‘A record of the music of the past season would not be complete were we to omit mentioning the performance of Berlioz’s ” Damnation de Faust,” under the direction of Mr. Charles Halle, who brought both his orchestra and choir to London expressly for the occasion.’

These performances were the making of the work in Britain and were followed by multiple performances up and down the country over the following years. The Hallé Choir became reacquainted with the work relatively recently, this time singing the original French text. In 2017 the tenors and basses of the choir were invited to join the Edinburgh Festival Chorus and the girls of the National Youth Choir of Scotland as part of the Edinburgh Festival in a performance in the Usher Hall of La Damnation de Faust by the Hallé conducted by Sir Mark Elder. For many of the choir, including myself, it was a first experience of Edinburgh during Festival time and that experience was a memorable one, not just for the choir, but for the reviewers. Keith Bruce writing in the Scotsman praised ‘vast palette of choral sound performed to a very high standard’, and on the website theoperacritic.com, Catriona Graham found ‘The dynamic range was impressive – chorus masters Christopher Bell and Matthew Hamilton had worked them well.’

February 10th, 2019 saw the work return to Manchester with Mark Elder and even larger forces. On this occasion the Hallé Choir (with the women joining the men this time), and the Hallé Children’s Choir and Youth Training Choir were reinforced by tenors and basses from the London Philharmonic and Leeds Philharmonic Choirs for a performance that Rohan Shotton writing on bachtrack.com called ‘stellar’:

‘The combined choral forces… gave one of the most thrilling choral performances I have witnessed on a concert stage. The singing was remarkably unwavering clear in diction for such large numbers (332 by my count), and while their sound was abundantly attractive in a huge Easter Hymn, they entered the spirit of the piece was thrilling aplomb at every opportunity. In the bawdy Auerbach drinking songs of Part 2 they swayed with convincing insobriety in the Choir Stalls, while the earlier peasant tunes seemed to find great fun in the bucolic cries of “Landerira”. The augmentation of the chorus with supplementary tenors and basses was a shrewd move, making for a superbly thrilling demonic chorus of the final scene, each cry of “Has!” thrown out into the auditorium with renewed vigour. However, the passage which will live longest in the memory was the profoundly moving redemption provided by the children’s and youth choirs from the aisles of the Stalls.’

Rohan Shotton, bachtrack.com, February 12th 2019

So, following this Hallé Choir ‘first performance in 1880’, as I mentioned in the introduction, there were only two other important premieres or first performances in the following 100 years involving the choir, the first concert performance of Constant Lambert’s Rio Grande, and the world premiere of Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antartica. I will cover the circumstances surrounding the premiere of Rio Grande in the second part of this blog, and follow it by discussing how the last thirty years has seen a significant growth in the number of new works commissioned for the Hallé Choir or new works in which the choir has been otherwise involved, including a new work whose first UK performance is upcoming early next year.

References:

Charles Hallé, Charles E. Hallé, and Marie Hallé, Life and Letters of Sir Charles Hallé (London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1896)

Rachel Hewerton, ‘Reshaping British Concert Life: Tracking the Performance History of Hector Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust in Nineteenth-Century Britain’, (University of California Riverside, 2019)

Michael Kennedy, The Hallé Tradition: A Century of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1960)

D. Kern Holoman, Damnation de Faust, La, (Oxford University Press, 2002) <https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000002474>.

Leanne Langley, ‘Agency and Change: Berlioz in Britain, 1870-1920’, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 132 (2007), pp. 306-48.

Henry C. Lunn, ‘The London Musical Season’, The Musical Times and Singing Class Circular, 21 (1880), pp. 385-87.

The Guardian newspaper archive

The Times newspaper archive

theoperacritic.com

bachtrack.com

scotsman.com

Leave a comment